Case Study of Two Alternative Russian Media a Thesis Submitted in P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minsk II a Fragile Ceasefire

Briefing 16 July 2015 Ukraine: Follow-up of Minsk II A fragile ceasefire SUMMARY Four months after leaders from France, Germany, Ukraine and Russia reached a 13-point 'Package of measures for the implementation of the Minsk agreements' ('Minsk II') on 12 February 2015, the ceasefire is crumbling. The pressure on Kyiv to contribute to a de-escalation and comply with Minsk II continues to grow. While Moscow still denies accusations that there are Russian soldiers in eastern Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly admitted in March 2015 to having invaded Crimea. There is mounting evidence that Moscow continues to play an active military role in eastern Ukraine. The multidimensional conflict is eroding the country's stability on all fronts. While the situation on both the military and the economic front is acute, the country is under pressure to conduct wide-reaching reforms to meet its international obligations. In addition, Russia is challenging Ukraine's identity as a sovereign nation state with a wide range of disinformation tools. Against this backdrop, the international community and the EU are under increasing pressure to react. In the following pages, the current status of the Minsk II agreement is assessed and other recent key developments in Ukraine and beyond examined. This briefing brings up to date that of 16 March 2015, 'Ukraine after Minsk II: the next level – Hybrid responses to hybrid threats?'. In this briefing: • Minsk II – still standing on the ground? • Security-related implications of the crisis • Russian disinformation -

Russian M&A Review 2017

Russian M&A review 2017 March 2018 KPMG in Russia and the CIS kpmg.ru 2 Russian M&A review 2017 Contents page 3 page 6 page 10 page 13 page 28 page 29 KEY M&A 2017 OUTLOOK DRIVERS OVERVIEW IN REVIEW FOR 2018 IN 2017 METHODOLOGY APPENDICES — Oil and gas — Macro trends and medium-term — Financing – forecasts sanctions-related implications — Appetite and capacity for M&A — Debt sales market — Cross-border M&A highlights — Sector highlights © 2018 KPMG. All rights reserved. Russian M&A review 2017 3 Overview Although deal activity increased by 13% in 2017, the value of Russian M&A Deal was 12% lower than the previous activity 13% year, at USD66.9 billion, mainly due to an absence of larger deals. This was in particular reflected in the oil and gas sector, which in 2016 was characterised by three large deals with a combined value exceeding USD28 billion. The good news is that investors have adjusted to the realities of sanctions and lower oil prices, and sought opportunities brought by both the economic recovery and governmental efforts to create a new industrial strategy. 2017 saw a significant rise in the number and value of deals outside the Deal more traditional extractive industries value 37% and utility sectors, which have historically driven Russian M&A. Oil and gas sector is excluded If the oil and gas sector is excluded, then the value of deals rose by 37%, from USD35.5 billion in 2016 to USD48.5 billion in 2017. USD48.5bln USD35.5bln 2016 2017 © 2018 KPMG. -

MEMO. Nº. 52/2017 – SCOM

00100.096648/2017-00 MEMO. nº. 52/2017 – SCOM Brasília, 21 de junho de 2017 A Sua Excelência a Senhora SENADORA REGINA SOUSA Assunto: Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334 Senhora Presidente, Nos termos do parágrafo único do art. 6º da Resolução do Senado Federal nº. 19 de 2015, encaminho a Vossa Excelência a Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334, sob o título de “Criminalização Da Apologia Ao Comunismo”, que alcançou, no período de 09/06/2017 a 20/06/2017, apoiamento superior a 20.000 manifestações individuais, conforme a ficha informativa em anexo. Respeitosamente, Dirceu Vieira Machado Filho Diretor da Secretaria de Comissões Senado Federal – Praça dos Três Poderes – CEP 70.165-900 – Brasília DF ARQUIVO ASSINADO DIGITALMENTE. CÓDIGO DE VERIFICAÇÃO: CE7C06D2001B6231. CONSULTE EM http://www.senado.gov.br/sigadweb/v.aspx. 00100.096648/2017-00 ANEXO AO MEMORANDO Nº. 52/2017 – SCOM - FICHA INFORMATIVA E RELAÇÃO DE APOIADORES - Senado Federal – Praça dos Três Poderes – CEP 70.165-900 – Brasília DF ARQUIVO ASSINADO DIGITALMENTE. CÓDIGO DE VERIFICAÇÃO: CE7C06D2001B6231. CONSULTE EM http://www.senado.gov.br/sigadweb/v.aspx. 00100.096648/2017-00 Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334 TÍTULO Criminalização Da Apologia Ao Comunismo DESCRIÇÃO Assim como a Lei já prevê o "Crime de Divulgação do Nazismo", a apologia ao COMUNISMO e seus símbolos tem que ser proibidos no Brasil, como já acontece cada vez mais em diversos países, pois essa ideologia genocida causou males muito piores à Humanidade, massacrando mais de 100 milhões de inocentes! (sic) MAIS DETALHES O art. 20 da Lei 7.716/89 estabeleceu o "Crime de Divulgação do Nazismo": "§1º - Fabricar, comercializar, distribuir ou veicular, símbolos, emblemas, ornamentos, distintivos ou propaganda que utilizem a cruz suástica ou gamada, para fins de divulgação do nazismo. -

Russian Federation 2012

RUSSIAN FEDERATION 2012 Short-term prognosis RUSSIAN FEDERATION 2012 Short-term prognosis Editors: Karmo Tüür & Viacheslav Morozov Editors: Karmo Tüür & Viacheslav Morozov Editor of “Politica” series: Rein Toomla Copyright: Individual authors, 2012 ISSN 1736–9312 Tartu University Press www.tyk.ee CONTENT Introduction ..................................................................................... 7 Evaluation of the last prognosis. Erik Terk ...................................... 9 INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS Political system. Viacheslav Morozov .............................................. 21 Legal system. Aleksey Kartsov .......................................................... 26 Economy. Raivo Vare ...................................................................... 30 Energy sector. Andres Mäe .............................................................. 35 The Russian Military. Kaarel Kaas ................................................. 40 The political role of the Russian Orthodox Church. Alar Kilp ...... 45 Mass media development. Olga Chepurnaya ................................. 49 Civil society. Zhanna Chernova ...................................................... 54 Demography of the regions. Aimar Altosaar ................................... 58 Nationalities policy of Russia. Konstantin Zamyatin ...................... 62 Center – Northern Caucasus. Nona Shahnazarian ....................... 67 Foreign relations of Russian regions. Eero Mikenberg .................... 71 EXTERNAL RELATIONS Russia and the WTO. Kristjan -

Russian Media Organisations Banned for Three Years in Ukraine Ukraine

Russian Media Organisations Banned for Three Years in Ukraine Ukraine abides by all commitments and international standards of ensuring freedom of speech in spite of the continued Russian aggression, the occupation of Ukraine’s sovereign territory in violation of all international rules, the use by the aggressor State of some media of various forms of ownership with a view to carrying out special information operations in the information field of Ukraine and other States by its security services. This is confirmed by Ukraine’s performance in Press Freedom Index 2018, compiled by the international organization Reporters Without Borders. According to the rating, Ukraine has moved one position up and is now ranked 101st. With regard to the concern expressed in the alert published on the Council of Europe Platform on the alleged prohibition of Russian media in Ukraine, the following information shall be taken into account. It is common knowledge that since 2014 Ukraine has been subjected to hybrid aggression of the Russian Federation. This aggression manifested not only in the illegal occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and military aggression in Donetsk and Luhansk regions but also in an unprecedented disinformation and propagandistic campaign against Ukraine. With a view to establishing a legal framework to counter the aggression, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted the Law of Ukraine “On Sanctions” (hereinafter referred to as the Law) on 14 August 2014. Article 1 of the Law states that, with a view to protecting national interests, national security, the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, countering terrorist activities, as well as preventing infringement of rights and restoring infringed rights, freedoms and lawful interests of citizens of Ukraine, society and the state special economic and other restrictive measures (hereinafter referred to as ‘sanctions’) may be taken. -

Russia's Silence Factory

Russia’s Silence Factory: The Kremlin’s Crackdown on Free Speech and Democracy in the Run-up to the 2021 Parliamentary Elections August 2021 Contact information: International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) Rue Belliard 205, 1040 Brussels, Belgium [email protected] Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 II. INTRODUCTION 6 A. AUTHORS 6 B. OBJECTIVES 6 C. SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND METHODOLOGY 6 III. THE KREMLIN’S CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 7 A. THE LEGAL TOOLKIT USED BY THE KREMLIN 7 B. 2021 TIMELINE OF THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 9 C. KEY TARGETS IN THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 12 i) Alexei Navalny 12 ii) Organisations and Individuals associated with Alexei Navalny 13 iii) Human Rights Lawyers 20 iv) Independent Media 22 v) Opposition politicians and pro-democracy activists 24 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS TRIGGERED BY THE CRACKDOWN 27 A. FREEDOMS OF ASSOCIATION, OPINION AND EXPRESSION 27 B. FAIR TRIAL RIGHTS 29 C. ARBITRARY DETENTION 30 D. POLITICAL PERSECUTION AS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY 31 V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 37 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY “An overdose of freedom is lethal to a state.” Vladislav Surkov, former adviser to President Putin and architect of Russia’s “managed democracy”.1 Russia is due to hold Parliamentary elections in September 2021. The ruling United Russia party is polling at 28% and is projected to lose its constitutional majority (the number of seats required to amend the Constitution).2 In a bid to silence its critics and retain control of the legislature, the Kremlin has unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on the pro-democracy movement, independent media, and anti-corruption activists. -

Labor Migration and Integration Final.Pdf

LABOR MIGRATION AND MIGRANT INTEGRATION POLICY IN GERMANY AND RUSSIA Edited by Marya S. Rozanova SAINT PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY Copyright © 2016 by Saint Petersburg State University; Print House “Scythia-Print;” Center for Civil, Social, Scientifc, and Cultural Initiatives “STRATEGIA” Recommended for publication and published by Saint Petersburg State University Center for Civil, Social, Scientifc, and 1/3 Smolnii Street, entrance 7 Cultural Initiatives “STRATEGIA” Saint Petersburg 191124 22-24 7th Krasnoarmeiskaya Street Russia Saint Petersburg 190005 Russia All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or uti- lized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafer invented, including photocopying, microflming, and recording, or in any information stor- age or retrieval system, without the prior permission from the publisher, except by a review- er who may quote passages in a review. Saint Petersburg State University; the Center for Civil, Social, Scientifc, and Cultural Initiatives “STRATEGIA;” and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Russia do not take in- stitutional positions on public policy issues; the views and recommendations presented in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of these organizations, their staf, or trustees. Labor migration and migrant integration policy in Germany and Russia / edited by Marya S. Rozanova. p. cm. Copyeditor and Proofreader: Larissa Galenes Primary Proofreader: Herbert Horn ISBN 978-5-98620-209-9 Typeset and printed on acid-free paper by Te Print House “Scythia-Print” 10 Bolshaya Pushkarskaya Street Saint Petersburg 197198 Russia Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction: Migration Policy in Russia and Germany: Challenges and Perspectives (Conference Overview) 1 Marya S. -

Are Cookie Banners Indeed Compliant with the Law? Cristiana Santos, Nataliia Bielova, Célestin Matte

Are cookie banners indeed compliant with the law? Cristiana Santos, Nataliia Bielova, Célestin Matte To cite this version: Cristiana Santos, Nataliia Bielova, Célestin Matte. Are cookie banners indeed compliant with the law?: Deciphering EU legal requirements on consent and technical means to verify compli- ance of cookie banners. Technology and Regulation, Tilburg University, 2020, 2020, pp.91-135. 10.26116/TECHREG.2020.009. hal-02875447v2 HAL Id: hal-02875447 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-02875447v2 Submitted on 23 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Are cookie banners indeed compliant with the law? Deciphering EU legal requirements on consent and technical means to verify compliance of cookie banners Cristiana Santos, Nataliia Bielova, Célestin Matte Inria, France [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we describe how cookie banners, as a consent mechanism in web applications, should be designed and implemented to be compliant with the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR, defining 22 legal requirements. While some are provided by legal sources, others result from the domain expertise of computer scientists. We perform a technical assessment of whether technical (with computer science tools), manual (with a human operator) or user studies verification is needed. -

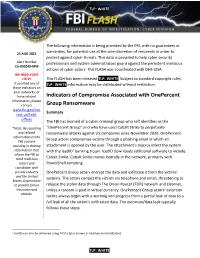

Indicators of Compromise Associated with Onepercent Group Ransomware

TLP: WHITE The following information is being provided by the FBI, with no guarantees or 23 AUG 2021 warranties, for potential use at the sole discretion of recipients in order to protect against cyber threats. This data is provided to help cyber security Alert Number professionals and system administrators guard against the persistent malicious CU-000149-MW actions of cyber actors. This FLASH was coordinated with DHS-CISA. WE NEED YOUR HELP! This FLASH has been released TLP: WHITE. Subject to standard copyright rules, If you find any of TLP: WHITE information may be distributed without restriction. these indicators on your networks, or have related Indicators of Compromise Associated with OnePercent information, please contact Group Ransomware www.fbi.gov/con Summary tact-us/field- offices The FBI has learned of a cyber-criminal group who self identifies as the *Note: By reporting “OnePercent Group” and who have used Cobalt Strike to perpetuate any related ransomware attacks against US companies since November 2020. OnePercent information to the Group actors compromise victims through a phishing email in which an FBI, you are assisting in sharing attachment is opened by the user. The attachment’s macros infect the system information that with the IcedID1 banking trojan. IcedID downloads additional software to include allows the FBI to track malicious Cobalt Strike. Cobalt Strike moves laterally in the network, primarily with actors and PowerShell remoting. coordinate with private industry OnePercent Group actors encrypt the data and exfiltrate it from the victims’ and the United systems. The actors contact the victims via telephone and email, threatening to States Government to prevent future release the stolen data through The Onion Router (TOR) network and clearnet, intrusions and unless a ransom is paid in virtual currency. -

Pride & Prejudice

» AUTUMN 2005 VOL 5 ISSUE 3 NEWSLETTER ISSN 1378-577X www.ilga-europe.org PRIDEPRIDE && PREJUDICEPREJUDICE » Amnesty International on freedom of expression » Chisinau,( Bucharest, Warsaw, Riga… is Moscow next? » free speech versus religious belief The European Region of the International Lesbian and Gay Association avenue de Tervueren 94 Bank account # 310-1844088-10 1040 Brussels, Belgium ING Belgique Phone +32 2 609 54 10 ETT-CINQUANTENAIRE Fax +32 2 609 54 19 avenue de Tervueren 10 [email protected] 1040 ETTERBEEK www.ilga-europe.org IBAN BE41 3101 8440 8810 BIC (SWIFT): BBRUBEBB Table of Contents 3 Staff news Message from Patricia 4 ILGA European Conference 5 Revising ILGA-Europe Constitution A very warm welcome to the autumn edition of our 6 News from ILGA-Europe Newsletter! 7 Queer Solidarity Hope you all had a nice summer. For some of us, summer was a 8 Amnesty International on freedom of expression 12 Moldova: court overruled a ban on LGBT demonstration relaxing and carefree period; for others, it was a frantically busy 12 Poland: law and justice for all? time, organising pride events. For many in Europe, the summer 14 Latvia: homophobia tales to the streets ended up being very hot! While in many places the Pride events 16 Romania: victory for LGBT community were as colourful and celebratory as usual, in some parts of 17 Russia: passions around pride event Europe they resulted in bitter battles against discrimination and 18 Netherlands: freedom of speech v religious belief homophobia. LGBT people in some corners of Europe have had 19 News clips to challenge not only ultra nationalists and Christian fundamental- ists, but also Prime Ministers (Latvia) and city mayors (Chisinau,( Warsaw, Bucharest) for their right to peaceful demonstration and The ILGA-Europe Newsletter is Anmeghichean, Stephen Barris, the quarterly newsletter of Anders Dahlbeck, Diane Fisher, expression. -

Russia's 'Dictatorship-Of-The-Law' Approach to Internet Policy Julien Nocetti Institut Français Des Relations Internationales, Paris, France

INTERNET POLICY REVIEW Journal on internet regulation Volume 4 | Issue 4 Russia's 'dictatorship-of-the-law' approach to internet policy Julien Nocetti Institut français des relations internationales, Paris, France Published on 10 Nov 2015 | DOI: 10.14763/2015.4.380 Abstract: As international politics' developments heavily weigh on Russia's domestic politics, the internet is placed on top of the list of "threats" that the government must tackle, through an avalanche of legislations aiming at gradually isolating the Russian internet from the global infrastructure. The growth of the Russian internet market during the last couple of years is likely to remain secondary to the "sovereignisation" of Russia's internet. This article aims at understanding these contradictory trends, in an international context in which internet governance is at a crossroads, and major internet firms come under greater regulatory scrutiny from governments. The Russian 'dictatorship-of-the-law' paradigm is all but over: it is deploying online, with potentially harmful consequences for Russia's attempts to attract foreign investments in the internet sector, and for users' rights online. Keywords: Internet governance, Russia, RuNet Article information Received: 10 Jul 2015 Reviewed: 03 Sep 2015 Published: 10 Nov 2015 Licence: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist that have influenced the text. URL: http://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/russias-dictatorship-law-approach-internet-policy -

The Kremlin's Proxy War on Independent Journalism

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford WEEDING OUT THE UPSTARTS: THE KREMLIN’S PROXY WAR ON INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM by Alexey Eremenko Trinity Term 2015 Sponsor: The Wincott Foundation 1 Table of Contents: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 INTRODUCTION 4 1. INTERNET & FREEDOM 7 1.1 STATISTICAL OVERVIEW 7 1.2 MEDIA REGULATIONS 8 1.3 SITES USED 9 2. ‘LINKS OF THE GODDAMN CHAIN’ 12 2.1 EDITORIAL TAKEOVER 12 2.2 DIRECT HIT 17 2.3 FINDINGS 22 3. THE MISSING LINKS 24 3.1 THE UNAFFECTED 24 3.2 WHAT’S NOT DONE 26 4. MORE PUTIN! A CASE STUDY IN COVERAGE CHANGE 30 4.1 CATEGORIES 30 4.2 KEYWORDS 31 4.3 STORY SUBJECTS 32 4.4 SENTIMENT ANALYSIS 32 5. CONCLUSIONS 36 BIBLIOGRAPHY 38 2 Acknowledgments I am immensely grateful, first and foremost, to the fellows at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, whose expertise and good spirits made for a Platonic ideal of a research environment. James Painter and John Lloyd provided invaluable academic insight, and my past and present employers at the Moscow Times and NBC News, respectively, have my undying gratitude for agreeing to spare me for three whole eventful months, an eternity in the news gathering business. Finally, my sponsor, the Wincott Foundation, and the Reuters Institute itself, believed in me and my topic enough to make this paper possible and deserve the ultimate credit for whatever meager contribution it makes to the academia and, hopefully, upholding the freedom of speech in the world. 3 Introduction “Freedom of speech was and remains a sacrosanct value of the Russian democracy,” Russian leader Vladimir Putin said in his first state of the nation in 2000.