Northeast Avalon Municipal Service Sharing Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newfoundland Antique and Classic Car Club (NACCC) April – June 2008

Newfoundland Antique and Classic Car Club (NACCC) April – June 2008 Iron Wood Shopping Mall, Richmond BC (Picture compliments of Walter and Shirley LaCour) President’s Message Another cruising season has started and Classic Wheels 2008 Car show is now history. Time surely flies when we are having fun getting prepared for the show. I would like to thank all the members who participated in the show whether it was helping to plan the car show, showing your car, volunteering with ticket sales or whatever. Without your help it would be impossible to do such an event. Congratulations to all the trophy winners. It is very difficult to choose from such beautiful classic automobiles. According to the list of activities and events in the calendar it seems we will have a very busy season. We suggest you refer to the calendar for events that will interest you. Of special note is a show and shine on July 1 at the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 1 for our veterans. A large attendance will show our thanks to all the veterans from past and present for the sacrifice they made for us. There will be information in the newsletter pertaining to this. Our car club plans to visit the A&W on Cunard Crescent, in Donavans on a regular basis every second Thursday night. Owner, Scott Bartlett, promises to make our visits interesting and will give the club a percentage for A&W catalogue merchandise purchased. Please remember cruising and socializing is what our club is all about so get out and meet up with the members and enjoy our short cruising season. -

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018 Baie Verte Bay St George Waste Management Committee Cape St George Channel Port au Basques City of St John's Gander Greens Habour Lourdes New-Wes-Valley Northern Peninsula Regional Service Board Paradise Pasadena Sandy Cove Trinity Bay North Twillingate 2017 Baie Verte Carbonear Corner Brook Farm and Market, Clarenville Grand Falls-Windsor Logy Bay-Middle Cove-Outer Cove Makkovik Memorial University, Grenfell Campus Paradise Pasadena Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Robert's Arm Sandy Cove St. Lawrence St. John's Twillingate 2016 2015 Brigus Baie Verte Burin Corner Brook Carmanville Discovery Regional Service Board Comfort Cove - New Stead Happy Valley - Goose Bay Fogo Island Logy Bay - Middle Cove - Outer Cove Gambo Sandy Cove Gander St. John's McIver’s Sunnyside North West River Witless Bay Point Leamington 2014 Burgeo Carbonear Conception Bay South (CBS) Lewisporte Paradise Portugal Cove - St. Phillip’s St. Alban’s St. Anthony (NorPen Regional Service Board) St. George’s St. John's Whitbourne Witless Bay 2013 Bird Cove Kippens Bishop's Falls Lark Harbour Campbellton Marystown Clarenville New Perlican Conception Bay South (CBS) NorPen Regional Service Board Conne River Old Perlican Corner Brook Paradise Deer Lake Pasadena Dover Placentia Flatrock Port au Choix Gambo Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Grand Bank Springdale Happy Valley - Goose Bay Stephenville Harbour Grace Twillingate 2011 Botwood Conception Bay South (CBS) Cape Broyle Conception Harbour Gander Conne River Glovertown Corner Brook Sunnyside Deer Lake Harbour Main – Chapel’s Cove – Gambo Lakeview Glenwood Holyrood Grand Bank Logy Bay Harbour Breton Appleton Heart’s Delight - Islington Arnold’s Cove Irishtown – Summerside Bay Roberts Kippens Baytona Labrador City Bonavista Lawn Campbellton Leading Tickles Carbonear Long Harbour & Mount Arlington Centreville Heights Channel - Port aux Basques Makkovik (Labrador) Colliers Marystown 2011 cont. -

Arnnl Recognizes Nursing Excellence

Vol. XXXVI No. 3 September 2015 The Magazine of the Association of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador IN THIS ISSUE ARNNL RECOGNIZES NURSING Council Bestows Honorary ARNNL Membership – 5 Upcoming Changes in Licensure Renewal Process – 7 EXCELLENCE ARNNL Continuing Education Teleconference Sessions – 11 PAGE 9 Technology Tips for Your Practice – 20 CONTENTS Message from the President ...........................................................................3 From the Executive Director’s Desk ................................................................4 ARNNL STAFF ARNNL Council Matters ..................................................................................5 Lynn Power, Executive Director 753-6173 I [email protected] Q & A: You Asked ............................................................................................6 Registration Update ........................................................................................7 Michelle Osmond, Director of Regulatory Services Canadian Nurses Protective Society ..............................................................8 753-6181 I [email protected] Nurses of Note ................................................................................................9 Lana Littlejohn, Director of Corporate Services Advanced Practice View ...............................................................................10 753-6197 I [email protected] ARNNL Continuing Education Teleconference Sessions ............................. 11 Trudy L. Button, Legal Counsel -

Municipal Plan 2014-2024

MUNICIPAL PLAN 2014-2024 TOWN OF PORTUGAL COVE-ST. PHILIP’S | SEPTEMBER 2014 | CONTACT INFORMATION: 100 LEMARCHANT ROAD | ST. JOHN’S, NL | A1C 2H2 | CANADA P. (709) 738-2500 | F. (709) 738-2499 WWW.TRACTCONSULTING.COM URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING ACT (2000) RESOLUTION TO ADOPT ............................................. 4 CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF PLANNERS (MCIP) CERTIFICATION ......................................................... 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Purpose of the Municipal Plan .................................................................................................. 6 1.1.1 Contents of the Municipal Plan ..................................................................................... 6 1.1.2 Other Reports, Studies & Comments ............................................................................. 7 1.1.3 Public Engagement ........................................................................................................ 7 1.1.4 Bringing the Municipal Plan into Effect ......................................................................... 8 1.1.5 Municipal Plan Administration ...................................................................................... 9 1.2 Summary of Community Research & Analysis .......................................................................... 9 1.2.1 Population Growth ...................................................................................................... -

Background Report City of Mount Pearl

DRAFT KENMOUNT HILL COMPREHENSIVE DEVELOPMENT SCHEME BACKGROUND REPORT CITY OF MOUNT PEARL | MARCH, 2018 | CONTACT INFORMATION: 100 LEMARCHANT ROAD | ST. JOHN’S, NL | A1C 2H2 | P. (709) 738-2500 | F. (709) 738-2499 WWW.TRACTCONSULTING.COM Kenmount Hill Comprehensive Development Scheme BACKGROUND REPORT City of Mount Pearl March 2018 Contact Information: Neil Dawe, President Tract Consulting Inc. P. 709.738.2500 F. 709.738.2499 email [email protected] www.tractconsulting.com Tract Consulting Inc. Proposed Development Plan for Lands Above the 190 Metre Contour: Kenmount Hill Comprehensive Development Scheme BACKGROUND REPORT Table of Contents 1. UNDERSTANDING THE PROJECT ............................................................................ 1 1.1. Purpose and objectives of the study ......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Study location ............................................................................................................................ 2 1.3. Land ownership patterns........................................................................................................... 3 1.4. Civic Policy Context ................................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Review of City of Mount Pearl planning documents, growth data and mapping .................... 4 1.6. Planning Methodology ............................................................................................................. -

Entanglements Between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen's

Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland by Liam Michael O’Flaherty M.A. (Political Science), University of British Columbia, 2008 B.A. (Honours), Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Liam Michael O’Flaherty, 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Approval Name: Liam Michael O’Flaherty Degree: Master of Arts Title: Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland Examining Committee: Chair: Elise Chenier Professor Willeen Keough Senior Supervisor Professor Mark Leier Supervisor Professor Lynne Marks External Examiner Associate Professor Department of History University of Victoria Date Defended/Approved: August 24, 2017 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between Newfoundland’s Irish Catholics and the largely English-Protestant backed Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU) in the early twentieth century. The rise of the FPU ushered in a new era of class politics. But fishermen were divided in their support for the union; Irish-Catholic fishermen have long been seen as at the periphery—or entirely outside—of the FPU’s fold. Appeals to ethno- religious unity among Irish Catholics contributed to their ambivalence about or opposition to the union. Yet, many Irish Catholics chose to support the FPU. In fact, the historical record shows Irish Catholics demonstrating a range of attitudes towards the union: some joined and remained, some joined and then left, and others rejected the union altogether. -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ABRAHAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADEYTON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS BEACH NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ALLANS ISLAND NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AMHERST COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANCHOR POINT NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANGELS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point APPLETON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AQUAFORTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARGENTIA NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARNOLDS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEN COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEY BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AVONDALE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACON COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGER NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGERS QUAY NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAIE VERTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAINE HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAKERS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARACHOIS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARENEED NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D ISLANDS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARTLETTS HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE EAST NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY BULLS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY DE VERDE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY L'ARGENT NL TORONTO, ON -

Student Handbook

Students Against Drinking & Driving (S.A.D.D.) Newfoundland & Labrador Student Handbook I N D E X SECTION 1: CHAPTER EXECUTIVE INFORMATION (WHITE PAGES) 1. EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS .............................................................................. 1 A) Election ................................................................................................... 1 B) Roles - President ..................................................................................... 2 - Vice-President ............................................................................. 3 - Vice-President of Finance ........................................................... 3 - Vice-President of Public Relations ............................................. 4 - Secretary ..................................................................................... 5 - Junior Rep .................................................................................. 6 - Teacher / Advisors ...................................................................... 7 C) Planning a Chapter Meeting .................................................................... 8 Sample Meeting Agenda .................................................................... 10 D) How to Write Minutes ............................................................................. 11 Sample Minutes Sheet ........................................................................ 12 Sample Monthly Report ..................................................................... 13 2. HOW TO PLAN A PROVINCIAL -

The Pattern of Glaciation on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland L’Histoire De La Glaciation De La Presqu’Île D’Avalon, À Terre-Neuve

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 05:31 Géographie physique et Quaternaire The pattern of glaciation on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland L’histoire de la glaciation de la presqu’île d’Avalon, à Terre-Neuve. Das Schema der Vereisung auf der Avalon-Halbinsel in Neufundland. Norm R. Catto Volume 52, numéro 1, 1998 Résumé de l'article L'histoire de la glaciation de la presqu'île d'Avalon a été établie à partir de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/004778ar l'étude des caractéristiques géomorphologiques, des stries et de la provenance DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/004778ar des blocs erratiques. On distingue trois phases dans un continuum de glaciation. Pendant la première phase, il y a eu accumulation et dispersion de Aller au sommaire du numéro la glace à partir de plusieurs centres. Au cours de la deuxième période, qui correspond au Wisconsinien supérieur, les glaciers ont atteint un maximum en étendue et en épaisseur. Le niveau marin abaissé a permis la formation d'un Éditeur(s) centre glaciaire à l'emplacement de la baie St. Mary. Le glacier en provenance de la partie continentale de Terre-Neuve a fusionné avec celui de la presqu'île Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal d'Avalon dans la baie de Plaisance, sur l'isthme et dans la baie de la Trinité. La troisième phase, caractérisée par la remontée du niveau marin et déclenchée ISSN par le recul de l'Inlandsis laurentidien au Labrador, a déséquilibré la calotte glaciaire de St. Mary. La déglaciation finale de la presqu'île d'Avalon a 0705-7199 (imprimé) commencé avant 10 100 ± 250 BP. -

RMHCNL Annual Report 2019

Weelo (Age 1) from St.Pierre et Miquleon. 1 stay, 501 nights. RONALD MCDONALD HOUSE CHARITIES® Newfoundland & Labrador Newfoundland & Labrador 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Natalia Williams (Age 6) Emma Clarke (Age 6) from Labrador City, NL. from Victoria, NL. 4 stays, 380 nights. 24 stays, 314 nights. Keeping families close TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION • MISSION • VALUES 4 Message from Board Chair & Executive Director 5 Board of Directors/Committees 6 FAMILY SUPPORT PROGRAMS 7 OUR IMPACT 2019 8 PULLING TOGETHER FOR FAMILIES 9 The Dedicated Volunteers 10 Strength in Numbers Volunteer Gathering 11 Helping Hand Awards 12 Adopt-a-Room Program 13 Community Events 14 McDonald’s: Our Founding and Forever Partner 15 Miss Achievement 16 OUR SIGNATURE EVENTS 17 Spare Some Love Bowling Event 18 “Fore” the Families Golf Classic 19 Red Shoe Crew – Walk for Families 20 Team RMHC 22 Sock It For Sick Kids & Their Families 23 Lights of Love Season of Giving Campaign 24 THANK YOU FROM OUR FAMILY TO YOURS 25 Donor Recognition 26 Seventh Birthday Celebration 28 MESSAGE FROM TREASURER 29 Financial Report 30 Vision Positively impact the health and lives of sick children, their families and their communities. Mission Ronald McDonald House Charities® Newfoundland and Labrador provides sick children and their families with a comfortable home where they can stay together in an atmosphere of caring, compassion and support close to the medical care and resources they need. Values Caring • Inclusion • Inspiration • Quality • Teamwork • Trust and Integrity MEET WEELO Generally, all mothers experiencing a high-risk pregnancy in Saint Pierre et Miquelon, a piece of French territory off the coast of Newfoundland, are referred to St. -

Rental Housing Portfolio March 2021.Xlsx

Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39 Avondale 3 3 Bareneed 1 1 Bay Bulls 1 1 10 12 Bay Roberts 4 15 19 Bay de Verde 1 1 Bell Island 90 10 16 116 Branch 1 1 Brigus 5 5 Brownsdale 1 1 Bryants Cove 1 1 Butlerville 8 8 Carbonear 26 4 31 10 28 99 Chapel Cove 1 1 Clarke's Beach 14 24 38 Colinet 2 2 Colliers 3 3 Come by Chance 3 3 Conception Bay South 36 8 14 3 16 77 Conception Harbour 8 8 Cupids 8 8 Cupids Crossing 1 1 Dildo 1 1 Dunville 11 1 12 Ferryland 6 6 Fox Harbour 1 1 Freshwater, P. Bay 8 8 Gaskiers 2 2 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Goobies 2 2 Goulds 8 4 12 Green's Harbour 2 2 Hant's Harbour 0 Harbour Grace 14 2 6 22 Harbour Main 1 1 Heart's Content 2 2 Heart's Delight 3 12 15 Heart's Desire 2 2 Holyrood 13 38 51 Islingston 2 2 Jerseyside 4 4 Kelligrews 24 24 Kilbride 1 24 25 Lower Island Cove 1 1 Makinsons 2 1 3 Marysvale 4 4 Mount Carmel-Mitchell's Brook 2 2 Mount Pearl 208 52 18 10 24 28 220 560 New Harbour 1 10 11 New Perlican 0 Norman's Cove-Long Cove 5 12 17 North River 4 1 5 O'Donnels 2 2 Ochre Pit Cove 1 1 Old Perlican 1 8 9 Paradise 4 14 4 22 Placentia 28 2 6 40 76 Point Lance 0 Port de Grave 0 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Portugal Cove/ St. -

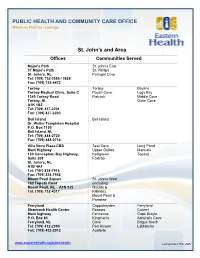

St. John's and Area

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY CARE OFFICE Where to Find Us - Listings St. John’s and Area Offices Communities Served Major’s Path St. John’s East 37 Major’s Path St. Phillips St. John’s, NL Portugal Cove Tel: (709) 752-3585 / 3626 Fax: (709) 752-4472 Torbay Torbay Bauline Torbay Medical Clinic, Suite C Pouch Cove Logy Bay 1345 Torbay Road Flatrock Middle Cove Torbay, NL Outer Cove A1K 1B2 Tel: (709) 437-2201 Fax: (709) 437-2203 Bell Island Bell Island Dr. Walter Templeton Hospital P.O. Box 1150 Bell Island, NL Tel: (709) 488-2720 Fax: (709) 488-2714 Villa Nova Plaza-CBS Seal Cove Long Pond Main Highway Upper Gullies Manuels 130 Conception Bay Highway, Kelligrews Topsail Suite 208 Foxtrap St. John’s, NL A1B 4A4 Tel: (70(0 834-7916 Fax: (709) 834-7948 Mount Pearl Square St. John’s West 760 Topsail Road (including Mount Pearl, NL A1N 3J5 Goulds & Tel: (709) 752-4317 Kilbride), Mount Pearl & Paradise Ferryland Cappahayden Ferryland Shamrock Health Center Renews Calvert Main highway Fermeuse Cape Broyle P.O. Box 84 Kingman’s Admiral’s Cove Ferryland, NL Cove Brigus South Tel: (709) 432-2390 Port Kirwan LaManche Fax: (709) 432-2012 Auaforte www.easternhealth.ca/publichealth Last updated: Feb. 2020 Witless Bay Main Highway Witless Bay Burnt Cove P.O. Box 310 Bay Bulls City limits of St. John’s Witless Bay, NL Bauline to Tel: (709) 334-3941 Mobile Lamanche boundary Fax: (709) 334-3940 Tors Cove but not including St. Michael’s Lamanche. Trepassey Trepassey Peter’s River Biscay Bay Portugal Cove South St.