A2J Evaluationl Report December 10.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Indian Legal Education a Blue Paper

HARVARD LAW SCHOOL PROGRAM ON THE LEGAL PROFESSION THE TRANSFORMATION OF INDIAN LEGAL EDUCATION A Blue Paper N.R. Madhava Menon Authored by N.R. Madhava Menon Published by the Harvard Law School Program on the Legal Profession © 2012 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Harvard Law School Program on the Legal Profession 23 Everett Street, G24 Cambridge, MA 02138 617.496.6232 law.harvard.edu/programs/plp Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ...............................................................................................................................................4 The Transformation of Indian Legal Education........................................................................................5 About the Author ...................................................................................................................................9 The Transformation of Indian Legal Education 3 Foreword FOREWORD The Law School Program on the Legal Profession was founded in 2004 to: Conduct, sponsor and publish world-class empirical research on the structure, norms and evolutionary dynamics of the legal profession; Innovate and implement new methods and content for teaching law students, prac- ticing lawyers and related professionals about the profession; and Foster broader and deeper connections bridging between the global universe of le- gal practitioners and the academy This manuscript by Professor N.R. Madhava Menon is part of a “blue paper” series of substantial essay, speech and opinion pieces on the legal profession selected by the program for distribution beyond the format or reach of traditional legal and scholarly media channels. Specifically, this text formed the basis for a keynote address delivered by Professor Menon at the program’s conference, The Indian Legal Pro- fession in the Age of Globalisation, held in October 2011 in New Delhi, India. We thank you for your interest and look forward to your feedback. -

Dr.S.D.Raajadevan, ...Vs the State of Tamil Nadu on 6 September, 2002

Dr.S.D.Raajadevan, .. ... vs The State Of Tamil Nadu on 6 September, 2002 Madras High Court Madras High Court Dr.S.D.Raajadevan, .. ... vs The State Of Tamil Nadu on 6 September, 2002 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS Dated: 06/09/2002 Coram The Honourable Mr.B.SUBHASHAN REDDY, CHIEF JUSTICE and The Hon'ble Mr.JUSTICE K.GOVINDARAJAN W.P.No.24625 of 2002 and W.P.No. 24696 of 2002 and Wp.Nos. 25014, 25015 & 25632 of 2002 S.Mazhaimeni Pandian, .. W.P.24625/02 Advocate. S.Packiaraj .. W.P.24696/02 K.Thanga Mohan .. W.P.25014/02 C.L.Shaji .. W.P.25015/02 Dr.S.D.Raajadevan, .. W.P.25632/02 Advocate. ..... Petitioners. -Vs- 1.The State of Tamil Nadu, Rep. by Chief Secretary to Govt., Fort St. George, Chennai.600009. .. 1st respondent, W.P.24625/02 & R5, W.P.25632/02. The Principal, Dr.Ambedkar Law College, Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/964487/ 1 Dr.S.D.Raajadevan, .. ... vs The State Of Tamil Nadu on 6 September, 2002 Madras High Court Complex, Chennai.1. .. 1st respondent, W.P.25632/02. 2.The Govt. of Tamil Nadu, Rep., its Secretary, Dept. of Law Fort St. George, Chennai.9. .. 1st respondent, W.Ps.25014 & 25015/02 & 2nd respondent,W.Ps.24625 &24696/02, & R4, W.P.25632/02. Director of Legal Studies, Dr. Ambedkar law College, Madras High Court Complex, Chennai.1. .. 2nd respondent, W.P.25632/02. 3.The Registrar, Tamil Nadu Dr. Ambedkar Law University, Poompozhil, 5 Greenways Road, Chennai.600 035. -

Handbook on Practice and Procedure and Office Procedure

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA HANDBOOK ON PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE AND OFFICE PROCEDURE 2017 CONTENTS Page Nos. Chapter I - Preliminary 1-4 1. Seal of the Supreme Court 1 2. Language 1 3. Definition 1 (i) Advocate 1 (ii) Advocate on-record 1 (iii) Appointed day 1 (iv) Allocated Matter 1-2 (v) Chief Justice 2 (vi) Code 2 (vii) Constitution 2 (viii) Court and this Court 2 (ix) Court appealed from 2 (x) Court Fee 2 (xi) High Court 2 (xii) Interlocutory Application 2 (xiii) Judge 3 (xiv) Judgment 3 (xv) Main Case 3 (xvi) Minor 3 (xvii) Miscellaneous Application 3 (xviii) Not taken up case 3 (xix) Prescribed 3 (xx) Record 3 (xxi) Respondent 3 (xxii) The Rules and Rules of the Court 3 (xxiii) Secretary General, Registrar and Registry 4 (xxiv) Senior Advocate 4 (xxv) Special Bench 4 (xxvi) Taxing Officer 4 (xxvii) Terminal List 4 Chapter II - Court and Jurisdiction 5-15 1. Appellate Jurisdiction 5 2. Extra-ordinary Appellate Jurisdiction 5 3. Original Jurisdiction 5-6 4. Extra-ordinary Original Jurisdiction 7 5. Advisory Jurisdiction 7-8 6. Inherent and Plenary Jurisdiction 8 7. Notes 8-15 8. Order XLVIII of the Rules 15 i Chapter III - Classification of Cases 16-21 1. Arbitration Petition 16 2. Civil Appeal 16-17 3. Contempt Petition (Civil) 17 4. Contempt Petition (Criminal) 17-18 5. Criminal Appeal 18 6. Election Petition 18 7. Original Suit 19 8. Petition for Special Leave to Appeal 19 9. Special Reference Case 19 10. Transferred Case 19 11. Transfer Petition 20 12. -

Vidya Prasarak Mandal's Thane Municipal Council's

{d{Yk{d{Yk 2009-2010 C LAW C M O T L s L ’ E M G P E V E STD. 1972 VIDYA PRASARAK MANDAL’S THANE MUNICIPAL COUNCIL’S LAW COLLEGE, THANE Affiliated to Mumbai University Recognised by Bar Council of India Accredited by NAAC 'Jnanadweepa', College Campus, Chendani Bunder Road, Thane - 400 601(MS), India Tel : 91 22 2536 4194 Email : [email protected] URL: www.vpmthane.org Dr. V. N. Bedekar Vidya Prasarak Mandal, Thane Managing Committee 2009-10 Jan. 26, 2010 Our Students sing “Am_Mm Xoe _hmZ.” VPM’s TMC Law College, Thane {d{Yk 2009-2010 Constitution Day 27th Jan 10 Felicitation of Adv. Shri Ram Apte Adv. Shri Ram Apte addressing on Senior Cormsel, Mumbai High Court “Emergency under Indian Constitution” Mr. Gaikwad singing ‘_m± VwPo gbm_’ Judge for Patriotic Song Competitions Mrs. Sachidevi Sannabhadati Dr. V. N. Bedekar Memorial debate 12th Feb. 2010 Welcome Inauguration by Shri. S. V. Karandikar Judges : totally engrossed Our team in action Ms. Nilakshi receiving 3rd best speaker prize Ms. Swati recovering certificate for participation Cultural Programme for entertainment Mrs. Mercy Thomas II LLB Student Compering Rangoli Welcomes Registration Captured Our Judge Adv. Smt. Meena Doshi Our Judge Retd. District Judge Shri Dilip Joshi Practical Training 2009-2010 Rahtoli Literacy Camp _amR>r {Xdg d dm{f©©H$ nm[aVmo{fH$ {dVaU gmohim 24/2/10 _amR>r {XZm{Z{_Îm KoÊ`mV Amboë`m {d{dY ñnY}gmR>rMo n[ajH$ gm¡. gwMoVm ghó~wÕo, lr. gwZrb nam§Ono d gm¡. Amem XmVma ñdmJV : gm¡. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae ROKKAM SUDARSANA RAO Former Member, State Finance Commission, GoAP 2015-2017 Former Dean, Faculty of Arts Ex-officio-Member, Academic Senate Former Director, SAARC Centre Former Head & Chairman, (PG) B O S Department of Economics Andhra University Visakhapatnam-530003, A.P, India E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Date of Birth & Age : July 1, 1953, Education: Degree Subject Year Institution Junior Dip. French Language 2010 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. P.G. Diploma Environmental 1992 School of Distance Education, Andhra Studies University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. Ph.D. Economics 1985 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. M.A. Economics 1977 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. B.A. Economics (Main) 1975 M.R. College, Vizianagaram, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. Employment Record: Position Held Name of the Institution Year Dean Faculty of Arts Department of Economics Since 2012 Chairman, (PG) BOS Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. Department of Economics April. 2008– Head Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. 2011 Department of Economics Professor of Economics 1998–Present Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. Department of Economics Associate Professor 1988–1998 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. Department of Economics Lecturer in Economics 1985–1998 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. School of Distance Education Asst. Director 1979–1985 Andhra University, Visakhapatnam A.P. Experience in Teaching and Research : 34 years and 4 months Specialization : Public Economics Government Finances Federal-State Fiscal Relations Tribal Economy Environmental Economics Indian Economic Problems Other Positions Held Position Employer/Organization Period Dean Faculty of Arts Department of Economics 2012-Present Chairman Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. -

Reportable in the Supreme Court of India Civil

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL/APPELLATE JURISDICTION TRANSFERRED CASE (CIVIL) NOS……………...OF 2020 [TRANSFER PETITIONS (CIVIL) NOS. 87-101 OF 2014] The Pharmacy Council of India .. Petitioner Versus Dr. S.K. Toshniwal Educational Trusts Vidarbha Institute of Pharmacy and Ors. Etc. .. Respondents WITH C. A. Nos. 2024-27 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.4124-4127 OF 2016] C. A. Nos. 2028-31 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.26480-26483 OF 2017] C. A. No. 2032 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.25160 OF 2017] C. A. No. 2035 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.608 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2036 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.606 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2033 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.9547 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2034 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.9546 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2037 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.9572 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2039 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.1171 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2038 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.1151 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2040 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.36434 OF 2017] C. A. No. 2041 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.26391 OF 2018] WRIT PETITION (C) NO.926 OF 2018 C. A. No. 2042 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.26373 OF 2018] C. A. No. 2043 of 2020 [SLP (C) NO.15328 OF 2019] & WRIT PETITION (C) NO.1501 OF 2019 2 J U D G M E N T M. R. Shah, J. Transfer Petitions (Civil) Nos. 87-101 of 2014 are allowed and Writ Petition Nos. -

LEGAL EDUCATION in INDIA: the MYTH and REALTY Dr

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 LEGAL EDUCATION IN INDIA: THE MYTH AND REALTY Dr. Reghunathan K.R Chairman BoS in Law, M.G University, Kottayam, Kerala; Faculty in Law, Government Law College, Ernakulam, Kerala. Abstract Ignorance of law is not an excuse. Understanding the law of a country is therefore inevitable. Here arises the significance of formal as well as informal legal education. However, the present legal education scenario in India is bleak. Frequent modifications and thirst for making changes for producing a new pattern made the law schools and colleges, laboratories. In this article the author narrates the existing legal education scenario in a nutshell and in conclusion made certain suggestions to improve the quality of legal education so that the students may become more responsible not only to the Bar and Bench; but also to the society. Key words: curriculum, etiquette, legal luminaries, misconduct, pedagogy, social engineer I. Introduction The ancient Egyptian law, Sumerian law and the Testament that date back to 1280 BC were some of the moral imperatives for a good society. Roman law was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, but its detailed rules were developed by professional jurists and were highly sophisticated. In medieval England, royal courts developed a body of precedent which later became the common law. In the medieval world, the Napoleonic and German Codes were the most influential. In India, from the Vedic period onwards the concept of dharma is the guiding force in administration, settlement of disputes and of the legal education. It is the duty of the King or his appointee to uphold dharma.1 Thus the strength of the society squarely related to the legal system and legal education. -

NMC-BILL-2016.Pdf

NATIONAL MEDICAL COMMISSION ACT, 2016 COMMENTS & OBSERVATIONS # Chapter Clause Section Point for Discussion General (1) There is nothing new in the proposed bill. All the functions enumerated therein are already being carried out by Medical Council of India presently under the aegis and provisions of present IMC Act which the proposed bill seeks to repeal. This is nothing else but “old wine in new bottle.” (2) The representative character of Medical Council of India and the fine balance between elected and nominated members has been completely given go bye in the process. In fact in the proposed bill there is total exclusion of elected members thereby making a mockery of democratic process. (3) There are other professional Councils under Health & FW department like Dental Council of India, Nursing Council of India, Pharmacy Council of India or under other departments like Bar Council of India. However proposed bill is brought for abolishing Medical Council of India only. There is no proposal in respect of other Councils or even a whisper about such a move. There is no legitimate reason for giving such step motherly treatment to Medical Council of India. (4) IMA totally opposed this Bill – In Toto (5) If implemented, non MBBS doctors can be the decision makers , and non MBBS doctors can get registered in NMR & start practising modern medicine. 1 Short Title 1 (2) Will it extend to J & K ? Present IMC Act specifically says “including Jammu & Kashmir.” 2 Definition Definition K The draft NMC Bill 2016, Sec 2, DEFINITONS,(k) states that “Medicine” means, unless the context demands otherwise, all branches of allopathic medicine such as surgery, paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology but does not extend to Indian systems of medicine such as homeopathy or to veterinary medicine, veterinary surgery and dentistry. -

Press Release Dated 10.06.2021 the Bar Council of India Received and Is

Press Release dated 10.06.2021 The Bar Council of India received and is still receiving thousands of letters and requests from the students of different Universities and law colleges of the country. Some heads of Institutions have sought guidance of the Council on the point of examinations and promotions of LL.B. Students. The concern of majority of students was to grant them promotions on the basis of past performance or through some other method of assessment. The students have expressed their grievances and assigned different sorts of reason for issuance of a general direction to all the Centers of Legal Education restraining them from holding any online or offline examination of any semester. Even many final year LL.B. students have raised similar grievances and their demands are also of the same nature. The Council vide its resolutions dated 29.05.2021 thoroughly discussed and deliberated over the issue. The related Judgments of Hon’ble Apex Court in Writ Petition (Civil) No.724/2020 titled as Praneeth K and Ors. versus University Grants Commission and Ors. and the Division Bench Judgment of Karnataka High Court was also perused by the Council. In fact, the Bar Council of India in its resolution dated 29.05.2021 had clearly expressed its views that it does not wish to involve itself in the matters of examinations and it is for the Universities to take their own decisions depending on the local conditions. Of course, the Bar Council of India’s concern is to maintain the standard of Legal Education and the Bar Council of India cannot compromise with the standard. -

Quality Assurance : What Role for Governments?

Quality assurance : What role for governments? P R O F E S S O R N.V.VARGHESE DIRECTOR CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH IN HIGHER EDUCATION (CPRHE/NUEPA) N E W D E L H I Massification of HE in India Indian HE system showed symptoms of revival in the present century – fast expanding system India entered a stage of massification of HE in this century The private sector contributes to more than 60 per cent of the enrolment Massification of enrolment and diversification of providers and multiplicity of regulators make quality assurance a challenging task Massification of HE in India Category Numbe r 2013 Universities and 412 national institutions Deemed universities 49 Private universities 201 Colleges 35,829 Enrolment in millions 29.6 GER (%) 21.1 Multiplicity of regulators University Grants Commission All India Council for Technical Education Distance Education Council Indian Council of Agricultural Research Bar Council of India National Council for Teacher Education Rehabilitation Council of India Medical Council of India, .Pharmacy Council of India Indian Nursing Council, Central Council of Homeopathy Dental Council of India , Central Council of Indian Medicine The regulatory bodies have their own EQA agencies Accreditation in India The regulatory bodies have their own accreditation agencies The most common and widely relied on is NAAC established by the UGC It is an autonomous body funded by the UGC NAAC model of assessment : the four phases Nationally evolved criteria for assessment Self-study by the institution Peer team -

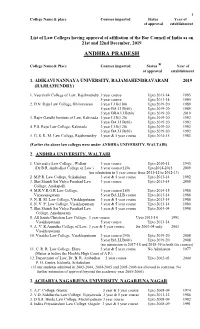

List of Law Colleges Having Deemed / Permanent / Temporary Approval Of

1 College Name& place Courses imparted Status Year of of approval establishment List of Law Colleges having approval of affiliation of the Bar Council of India as on 21st and 22nd December, 2019 ANDHRA PRADESH College Name& Place Courses imparted Status * Year of of approval establishment 1. ADIKAVI NANNAYA UNIVERSITY, RAJAMAHENDRAVARAM 2019 (RAJHAMUNDRY) 1. Veeravalli College of Law, Rajahmundry 3 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 2. D.N. Raju Law College, Bhimavaram 3 year LLB(180) Upto 2019-20 1989 5 year BA.LLB(60) Upto 2019-20 1989 5 year BBA.LLB(60) Upto 2019-20 2019 3. Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Law, Kakinada 3 year LLB(120) Upto 2019-20 1992 5 year BA.LLB(60) Upto 2019-20 1992 4. P.S. Raju Law College, Kakinada 3 year LLB(120) Upto 2019-20 1992 5 year BA.LLB(60) Upto 2019-20 1992 5. G. S. K. M. Law College, Rajahmundry 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2014-15 1983 (Earlier the above law colleges were under ANDHRA UNIVERSITY, WALTAIR) 2. ANDHRA UNIVERSITY, WALTAIR 1. University Law College , Waltair 3 year course Upto 2010-11 1945 (Dr.B.R. Ambedkar College of Law ) 5 year course(120) Upto2014-2015 2009 (no admission in 5 year course from 2011-12 to 2012-13) 2. M.P.R. Law College, Srikakulam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1992 3. Shri Shiridi Sai Vidya Parishad Law 3 year course Upto 2013-14 2000 College, Anakapalli 4. M.R.V.R.G.R Law College, 3 year course(180) Upto 2014-15 1986 Viziayanagaram 5 year BA.LLB course Upto 2013-14 1986 5. -

THE HARYANA PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES, 2006 (As Amended Upto 10Th May 2012)

THE HARYANA PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES, 2006 (as amended upto 10th May 2012) AN ACT to provide for establishment and incorporation of private universities in the State of Haryana for imparting higher education and to regulate their functions and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. Short title, extent and 1. (1) This Act may be called the Haryana Private Universities Act, 2006. commencement. (2) It extends to the whole of the State of Haryana. (3) It shall come into force at once. Definitions. 2. In this Act and in all the Statutes, Ordinances and Regulations made hereunder, unless the context otherwise requires,- (a) "All India Council for Technical Education" means All India Council for Technical Education established under the All India Council for Technical Education Act, 1987 (Central Act 52 of 1987); (aa) ‘Bar Council of India’ means the Bar Council of India constituted under the Advocates Act, 1961 (Central Act 25 of 1961);* (ab)‘campus’ means that area of the university in which it is established;”;* (b) "Council of Scientific and Industrial Research" means the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, an agency of the Central Government; (c) "Department of Science and Technology" means the Department of Science and Technology of the Central Government; (d) Omitted* (e) Omitted* (f) ‘employee’ means a person appointed by the university and includes a teacher, officer and any other staff of the university;* (fa) ‘existing private university’ means a university which has been established under the Haryana