China's Bold Strategy for Semiconductors--Zero-Sum Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and Their Subsidiaries and Affiliates

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and their Subsidiaries and Affiliates. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), 2 CFR 200.216, prohibits agreements for certain telecommunications and video surveillance services or equipment from the following companies as a substantial or essential component of any system or as critical technology as part of any system. • Huawei Technologies Company; • ZTE Corporation; • Hytera Communications Corporation; • Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Company; • Dahua Technology company; or • their subsidiaries or affiliates, Entering into agreements with these companies, their subsidiaries or affiliates (listed below) for telecommunications equipment and/or services is prohibited, as doing so could place the university at risk of losing federal grants and contracts. Identified subsidiaries/affiliates of Huawei Technologies Company Source: Business databases, Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd., 2017 Annual Report • Amartus, SDN Software Technology and Team • Beijing Huawei Digital Technologies, Co. Ltd. • Caliopa NV • Centre for Integrated Photonics Ltd. • Chinasoft International Technology Services Ltd. • FutureWei Technologies, Inc. • HexaTier Ltd. • HiSilicon Optoelectronics Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Dongguan) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Hong Kong) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Enterprise USA, Inc. • Huawei Global Finance (UK) Ltd. • Huawei International Co. Ltd. • Huawei Machine Co., Ltd. • Huawei Marine • Huawei North America • Huawei Software Technologies, Co., Ltd. • Huawei Symantec Technologies Co., Ltd. • Huawei Tech Investment Co., Ltd. • Huawei Technical Service Co. Ltd. • Huawei Technologies Cooperative U.A. • Huawei Technologies Germany GmbH • Huawei Technologies Japan K.K. • Huawei Technologies South Africa Pty Ltd. • Huawei Technologies (Thailand) Co. • iSoftStone Technology Service Co., Ltd. • JV “Broadband Solutions” LLC • M4S N.V. • Proven Honor Capital Limited • PT Huawei Tech Investment • Shanghai Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. -

TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation

TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation ANNUAL REPORT 2019 31 March 2020 1 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Part I Important Notes, Table of Contents and Definitions .................................................. 8 Part II Corporate Information and Key Financial Information ........................................... 11 Part III Business Summary .........................................................................................................17 Part IV Directors’ Report .............................................................................................................22 Part V Significant Events ............................................................................................................51 Part VI Share Changes and Shareholder Information .........................................................84 Part VII Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff .......................................93 Part VIII Corporate Governance ..............................................................................................113 Part IX Corporate Bonds .......................................................................................................... 129 Part X Financial Report............................................................................................................. 138 2 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Achieve Global Leadership by Innovation and Efficiency Chairman’s -

Annual Report 2018

08493 SMIC AR18 cover ENG (15.5mm).pdf 1 17/4/2019 下午5:36 Annual Report 2018 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2018 Annual Report Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation No.18 Zhangjiang Road, Pudong New Area, Shanghai 201203, The People’s Republic of China Tel : + 86 (21) 3861 0000 Fax : + 86 (21) 5080 2868 Website : www.smics.com (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 0981 Shanghai . Beijing . Tianjin . Jiangyin . Shenzhen . Hong Kong . Taiwan . Japan . Americas . Europe SMIC GLOBAL NETWORK TIANJIN SAN JOSE, CA, USA BEIJING MILAN, TOKYO, ITALY JAPAN JIANGYIN, JIANGSU SHANGHAI AVEZZANO, (Headquarters) ITALY SHENZHEN, GUANGDONG HSINCHU, TAIWAN HONG KONG (Representative) SMIC FAB SMIC MARKETING OFFICE SMIC REPRESENTATIVE OFFICE SMIC BUMPING FAB THE LARGEST ADVANCED FOUNDRY IN MAINLAND CHINA EMPOWERED TECHNOLOGY ENRICHED SERVICES, ENHANCED COMPETITIVENESS CONTENTS 05 Additional Information 07 Corporate Information 09 Financial Highlights 11 Letter to Shareholders 12 Business Review 17 Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operation 23 Directors and Senior Management 31 Report of the Directors 94 Corporate Governance Report 113 Social Responsibility 116 Independent Auditor’s Report 121 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 122 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 124 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 126 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 128 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements CAUTIONARY STATEMENT FOR PURPOSES OF THE “SAFE HARBOR” PROVISIONS OF THE PRIVATE SECURITIES LITIGATION REFORM ACT OF 1995 This annual report may contain, in addition to historical information, “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the “safe harbor” provisions of the U.S. -

Memory Lane and a Look Down the Road: China Progressing in NAND but Hurdles Remain

21 July 2019 | 12:06PM EDT Made in the USA or China Memory lane and a look down the road: China progressing in NAND but hurdles remain Mark Delaney, CFA +1(212)357-0535 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Allen Chang +852-2978-2930 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. We believe that China’s efforts to enter the global DRAM and NAND markets merit a Daiki Takayama +81(3)6437-9870 | deeper dive into how the memory industries have evolved over time, what impact [email protected] Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. China’s entry into other commodity tech industries (such as LEDs and solar) has had Toshiya Hari on fundamentals, where we believe the leading China-based memory companies +1(646)446-1759 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC stand at present with their efforts to enter the market (and the challenges that still Satoru Ogawa +81(3)6437-4061 | exist for entering the market — with GlobalFoundries as an example that [email protected] leading-edge semi production is difficult even for well-funded efforts), and what we Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. Alexander Duval believe all this means for the stocks of the established memory, drive, and semi +44(20)7552-2995 | [email protected] equipment companies. Goldman Sachs International Timothy Sweetnam, CFA With over $150 bn of semiconductors shipped to China in 2018, per the +1(212)357-7956 | [email protected] Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), and China domestic semi firms having Goldman Sachs & Co. -

TIMWE – Born Global Firm Case Study

CATÓLICA-LISBON, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS TIMWE – Born Global Firm Case Study Frederico José Castro Reis Marques December 2012 A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Business Administration, at CLSBE – Católica-Lisbon, School of Business & Economics. ABSTRACT Title: TIMWE – Born Global Firm Author: Frederico José Castro Reis Marques TIMWE is the Portuguese based company chosen to illustrate and serve as background to support the creation of a teaching case in Strategy, exploring the internationalization of a real company and the challenges undertaken by the process of being a born global firm, followed by a Teaching Note that can be used as a tool to help solving the case. TIMWE is a Portuguese owned company, founded in 2002, that offers mobile monetization solutions and services (entertainment, marketing and money) to its global clients (brands, end-consumers, media groups, mobile carriers and governments), by leveraging its in- house developed intellectual proprietary technology, wide network of connections, mobile expertise and local presence. The main focus of the business strategy always has been B2O (business-to-operators), and since the beginning of its foundation the company aimed to build a global reach. In 2011, it had 26 offices, employing more than 300 people, operating in 75 countries across the 5 continents, as well as partnerships with over 280 mobile carriers spread all over the world giving access to 3 billion mobile subscribers. The case was prepared with the intent of providing useful insights about an IT services Portuguese company that managed to internationalize and operate in several countries, on top of giving a generic overview of the industry where it acts and is doing business. -

Qikink Product & Price List

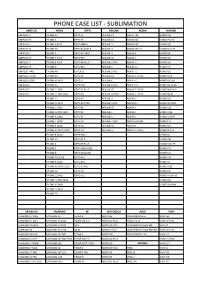

PHONE CASE LIST - SUBLIMATION ONEPLUS APPLE OPPO REALME NOKIA HUAWEI ONEPLUS 3 IPHONE SE OPPO F3 REALME C1 NOKIA 730 HONOR 6X ONEPLUS 3T IPHONE 6 OPPO F5 REALME C2 NOKIA 640 HONOR 9 LITE ONEPLUS 5 IPHONE 6 PLUS OPPO FIND X REALME 3 NOKIA 540 HONOR Y9 ONEPLUS 5T IPHONE 6S OPPO REALME X REALME 3i NOKIA 7 PLUS HONOR 10 LITE ONEPLUS 6 IPHONE 7 OPPO F11 PRO REALME 5i NOKIA 8 HONOR 8C ONEPLUS 6T IPHONE 7 PLUS OPPO F15 REALME 5S NOKIA 6 HONOR 8X ONEPLUS 7 IPHONE 8 PLUS OPPO RENO 2F REALME 2 PRO NOKIA 3.1 HONOR 10 ONEPLUS 7T IPHONE X OPPO F11 REALME 3 NOKIA 2.1 HONOR 7C ONEPLUS 7PRO IPHONE XR OPPOF13 REALME 3 PRO NOKIA 7.1 HONOR 5C ONEPLUS 7T PRO IPHONE XS OPPO F1 REALME C3 NOKIA 3.1 PLUS HONOR P20 ONEPLUS NORD IPHONE XS MAX OPPO F7 REALME 6 NOKIA 5.1 HONOR 6PLUS ONEPLUS X IPHONE 11 OPPO A57 REALME 6 PRO NOKIA 7.2 HONOR PLAY 8A ONEPLUS 2 IPHONE 11 PRO OPPO F1 PLUS REALME X2 NOKIA 7.1 PLUS HONOR NOVA 3i ONEPLUS 1 IPHONE 11 PRO MAX OPPO F9 REALME X2 PRO NOKIA 6.1 PLUS HONOR PLAY IPHONE 12 OPPO A7 REALME 5 NOKIA 6.1 HONOR 8X IPHONE 12 MINI OPPO R17 PRO REALME 5 PRO NOKIA 8.1 HONOR 8X MAX IPHONE 12 PRO OPPO K1 REALME XT NOKIA 2 HONOR 20i IPHONE 12 PRO MAX OPPO F9 REALME 1 NOKIA 3 HONOR V20 IPHONE X LOGO OPPO F3 REALME X NOKIA 5 HONOR 6 PLAY IPHONE 7 LOGO OPPO A3 REALME 7 PRO NOKIA 6 (2018) HONOR 7X IPHONE 6 LOGO OPPO A5 REALME 5S NOKIA 8 HONOR 5X IPHONE XS MAX LOGO OPPO A9 REALME 5i NOKIA 2.1 PLUS HONOR 8 LITE IPHONE 8 LOGO OPPO R98 HONOR 8 IPHONE 5S OPPO F1 S HONOR 9N IPHONE 4 OPPO F3 PLUS HONOR 10 LITE IPHONE 5 OPPO A83 (2018) HONOR 7S IPHONE 8 -

Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association No. 2/3, 4Th St

COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA Case No. 15 of 2018 In Re: Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association Informant No. 2/3, 4th Street, Judge Colony, Tambaram Sanatorium, Chennai- 600 047 Tamil Nadu. And 1. Fangs Technology Private Limited Opposite Party No. 1 Old Door No. 68, New Door No. 156 & 157, Valluvarkottam High Road, Nungambakkam, Chennai – 600 034 Tamil Nadu. 2. Vivo Communication Technology Company Opposite Party No. 2 Plot No. 54, Third Floor, Delta Tower, Sector 44, Gurugram – 122 003 Haryana. CORAM Mr. Sudhir Mital Chairperson Mr. Augustine Peter Member Mr. U. C. Nahta Member Case No. 15 of 2018 1 Appearance: For Informant – Mr. G. Balaji, Advocate; Mr. P. M. Ganeshram, President, TNCPDA and Mr. Babu, Vice-President, TNCPDA. For OP-1 – Mr. Vaibhav Gaggar, Advocate; Ms. Neha Mishra, Advocate; Ms. Aayushi Sharma, Advocate and Mr. Gopalakrishnan, Sales Head. For OP-2 – None. Order under Section 26(2) of the Competition Act, 2002 1. The present information has been filed by Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association (‘Informant’) under Section 19(1) (a) of the Competition Act, 2002 (the ‘Act’) alleging contravention of the provisions of Sections 3 and 4 of the Act by Fangs Technology Private Limited (‘OP- 1’) and Vivo Communication Technology Company (‘OP-2’) (collectively referred to as the ‘OPs’). 2. The Informant is an association registered under the Tamil Nadu Society Registration Act, 1975. Its stated objective is to protect the interest of the distributors from unfair trade practices and stringent conditions imposed by the manufacturers of consumer products. 3. OP-1 is engaged in the business of trading and distribution of mobile handsets under the brand name ‘VIVO’ and also provide marketing support to promote its products. -

Handset ODM Industry White Paper

Publication date: April 2020 Authors: Robin Li Lingling Peng Handset ODM Industry White Paper Smartphone ODM market continues to grow, duopoly Wingtech and Huaqin accelerate diversified layout Brought to you by Informa Tech Handset ODM Industry White Paper 01 Contents Handset ODM market review and outlook 2 Global smartphone market continued to decline in 2019 4 In the initial stage of 5G, China will continue to decline 6 Outsourcing strategies of the top 10 OEMs 9 ODM market structure and business model analysis 12 The top five mobile phone ODMs 16 Analysis of the top five ODMs 18 Appendix 29 © 2020 Omdia. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. Handset ODM Industry White Paper 02 Handset ODM market review and outlook In 2019, the global smartphone market shipped 1.38 billion units, down 2.2% year-over- year (YoY). The mature markets such as North America, South America, Western Europe, and China all declined. China’s market though is going through a transition period from 4G to 5G, and the shipments of mid- to high-end 4G smartphone models fell sharply in 2H19. China’s market shipped 361 million smartphones in 2019, a YoY decline of 7.6%. In the early stage of 5G switching, the operator's network coverage was insufficient. Consequently, 5G chipset restrictions led to excessive costs, and expectations of 5G led to short-term consumption suppression. The proportion of 5G smartphone shipments was relatively small while shipments of mid- to high-end 4G models declined sharply. The overall shipment of smartphones from Chinese mobile phone manufacturers reached 733 million units, an increase of 4.2% YoY. -

Copy of Google VR Compatible Phones

Google VR Compatible Phones Apple Huawei LG Nokia Sony iPhone 6s Ascend D2 G Flex 2 7 Xperia X iPhone 6s Plus Ascend P6 G2 7 Plus** Xperia X Performance iPhone 7 Honor 10 ** G3 8 Xperia XZ Premium iPhone 7 Plus Honor 3 G3 LTE-A 8 Sirocco Xperia XZ1 iPhone 8 Honor 3X G750 G4 Lumia 930 Xperia XZ2 Compact iPhone 8 Plus Honor 6 G5 3 Xperia XZ2 Premium iPhone X** Honor 6 Plus GX F310L 5 Xperia XZs Honor 7 Nexus 4 Xperia Z Honor 8 Nexus 5 Xperia Z1 Asus Honor 9 Nexus 5X OnePlus Xperia Z1 S Padfone 2 Honor View 10 ** Optimus G N3 Xperia Z2 Padfone Infinity Mate 10 Porsche Design Optimus G E970 OnePlus Xperia Z2a Padfone Infinity 2 Mate 10 Pro ** Optimus GJ E975W X Xperia Z3 Zenfone 2 Mate 10 ** Optimus LTE2 2 Xperia Z3 + Zenfone 2 Deluxe Mate 10 ** Q6 3 Zperia Z3 + Dual Zenfone 2 Laser Mate 9 Pro V30** 3T Xperia Z3 Dual Zenfone 3 Mate RS Porsche Desing ** V30S ThinQ** 5 Xperia Z5 Zenfone 3 Max Mate S VU 3 F300L 5T** Zperia Z5 Dual Zenfone 3 Zoom Nova 2 X Venture Xperia Z5 Premium Zenfone 4 Max Nova 2 Plus Xperia ZL Zenfone 4 Max Pro Nova 2s ** Samsung Zenfone 5** P10 Microsoft Galaxy A3 P10 Lite Lumia 950 Galaxy A5 Xiaomi P10 Plus Galaxy A8 Black Shark Blackberry P20 ** Galaxy A8+ Mi 3 Motion P20 Lite ** Motorola Galaxy Alpha Mi 4 Priv P20 Pro ** DROID Maxx Galaxy C5 Pro Mi 4 LTE Z30 P8 DROID Turbo Galaxy C7 Mi 4c P9 DROID Turbo 2 Galaxy J5 Mi 4i Y7 DROID Ultra Galaxy J7 Mi 5 Google Y9 (2018) ** Mot X Force Galaxy J7 Pro Mi 5c PIxel Moto G4 Galaxy J7 V Mi 5s Pixel 2 Moto G4 Plus Galaxy K Zoom Mi 6 Pixel 2 XL ** Lenovo Moto G5 Galaxy Note 3 Neo -

China's BBK Giving Jitters to Other Android Brands Through Impactful

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 China’s BBK Giving Jitters to Other Android Brands through Impactful Marketing Strategies: A Study of the Indian Market Dr. Shikha Singh Assistant Professor Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Noida, Uttar Pradesh. India. Email: [email protected],[email protected] Prof. (Dr.) Tarun Kumar Singhal Professor Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Noida, Uttar Pradesh. India. Email: [email protected] Rupashi Sehgal BBA Student Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Noida, Uttar Pradesh. India. Email: [email protected] Tuhina Shukla BBA Student Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Noida, Uttar Pradesh. India. Email: [email protected] Abstract- Technology has flourished enormously over the last few decades, which has bought a revolution to the IT and Telecom sector. Cellphones which were primarily developed to make phone calls, have now turned out to be a necessity and are just not limited to calling. They have taken over many gadgets that are useful in day to day lives. Everyday people encounter a significant number of better and improved features being embedded into them. The end-users face a dilemma in selecting smartphones because of the cut-throat prices and a wide range of features being offered. Seeking the business opportunity, BBK Electronics Corporation (a Chinese company) tapped the Indian market with a different approach to capture the Indian market. BBK Electronics launched three different smartphone companies - VIVO, OPPO, ONE PLUS with different owners, USPs, marketing tactics as well as different features. -

The Perspective of China SOI Ecosystem

The Perspective of China SOI Ecosystem Jeffrey Wang CEO Simgui Technology World Semiconductor Conference ∙ Nanjing ∙ May 18, 2019 Why is China SOI Ecosystem Focused on RF-SOI? 2 China Smart Phone Market China Smart Phone Sales 2017 China Smart Phone Market 600 160% Million Unit 124% 128% 140% - 20 40 60 80 100 120 500 478 111% 459 422 431 120% Huawei 102 400 364 100% OPPO 78 88% vivo 72 80% 300 Apple 51 48% 60% MI 51 194 Million Unit Meizu 17 200 40% Gionee 15 16% 85 2% 11% 20% Samsung 11 100 38 Lephone 5 18 0% -4% Lenovo 2 - -20% Other 46 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Smart phone sales (million) Growth Rate % Smart phone sales (million) • China smart phone market reaches to 459 million • In 2017, Domestic smart phone suppliers counts units in 2017. However, growth rate becomes for 86% of China market. negative for the first time in 9 years. • Among them, Huawei, Oppo and Vivo are top three • China counts for 30% of worldwide market. suppliers and count for 56% of the China market. 3 Simgui Technology 5G Network Architecture-A High Level View 5G Network Architecture-A High Level View 5G Network Architecture-A High Level View 5G Network Architecture-A High Level View Self-ServiceChina Agile Operationis Motivated to C.Setup Unifed Database 5G Management Network User Carrier Rapid fault recovery is required for • Users want more speed. • OPEX reduction should be a network data status information (such as strategic priority for 5G. • 4G networks are hard- user data and policy data shared across pressed to meet current data• centers),CAPEX to as meet a percentagenetwork reliability of user demand. -

The Impact of China's Policies on Global Semiconductor

Moore’s Law Under Attack: The Impact of China’s Policies on Global Semiconductor Innovation STEPHEN EZELL | FEBRUARY 2021 China’s mercantilist strategy to grab market share in the global semiconductor industry is fueling the rise of inferior innovators at the expense of superior firms in the United States and other market-led economies. That siphons away resources that would otherwise be invested in the virtuous cycle of cutting-edge R&D that has driven semiconductor innovation for decades. KEY TAKEAWAYS ▪ No industry has an innovation dynamic quite like the semiconductor industry, where “Moore’s Law” has held for decades: The number of transistors on a microchip doubles about every two years, producing twice the processing power at half the cost. ▪ The pattern persists because the semiconductor industry vies with biopharmaceuticals to be the world’s most R&D-intensive industry—a virtuous cycle that depends on one generation of innovation to finance investment in the next. ▪ To continue heavy investment in R&D and CapEx, semiconductor firms need access to large global markets where they can compete on fair terms to amortize and recoup their costs. When they face excess, non-market-based competition, innovation suffers. ▪ China’s state-directed strategy to vault into a leadership position in the semiconductor industry distorts the global market with massive subsidization, IP theft, state-financed foreign firm acquisitions, and other mercantilist practices. ▪ Inferior innovators thus have a leg up—and the global semiconductor innovation curve is bending downward. In fact, ITIF estimates there would be 5,100 more U.S. patents in the industry annually if not for China’s innovation mercantilist policies.