An Unknown Inscription on Zakynthos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Zakynthos Island, Greece

ANNALS OF THE UPPER SILESIAN MUSEUM IN BYTOM ENTOMOLOGY Vol. 27 (online 004): 1–13 ISSN 0867-1966, eISSN 2544-039X (online) Bytom, 9.11.2018 LECH BOROWIEC1 , SEBASTIAN SALATA1,2 Notes on ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Zakynthos Island, Greece http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1481794 1 Department of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Taxonomy, University of Wrocław, Przybyszewskiego 65, 51-148 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] Abstract: Forty five ant species were recorded from the Zakynthos Island (Ionian Islands) in 2018, including seven not attributed to any formally described taxon. A comparison of ant fauna of Zakynthos with ant fauna of Samos islands is presented. Both islands have similar surface area (405.6 versus 476.4 km2) and are placed almost on the same latitude (37°) but represent the most western and the most eastern fauna complexes in Greece; 78 species and morphospecies were recorded from both islands but only 23 species are common. Key words: ants, Greece, East Aegean Islands, Samos, faunistics, taxonomy. INTRODUCTION Zakynthos is a Greek island placed in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, placed 13.5 km south of Kephalonia – the largest Ionian island, and 18 km west of the Peloponnese. It is also a separate regional unit of the Ionian Islands Region. The area of the island is 405.55 km2 and it is 37 km long and 19 km wide. Its coastline is roughly 123 km. The island is very diverse, with a mountainous plateau on its western half, steep cliffs on southwest coast, and densely populated and fertile plain, with long sandy beaches and several isolated hills, on the eastern part. -

Excursão Shore2shore

Visita Panorâmica a Zakinthos Itinerário Encontro no porto pelo nosso guia com o cartaz Shore2Shore. A nossa viagem a Zakinthos começa na cidade de Zante e levar-nos-á à nossa primeira paragem na aldeia de Bohali, onde os visitantes podem desfrutar da vista deslumbrante da cidade. A partir daí dirigimo-nos para a aldeia de Volimes, onde teremos a oportunidade de comprar produtos locais tais como azeite, mel e vários artesanatos. A próxima paragem será a famosa Praia dos Naufrágios, que pode ser fotografada de cima através da plataforma de observação perto da aldeia de Anafonitria. Como já estamos na aldeia de Anafonitria, iremos visitar o Mosteiro de Panagia Anafonitria, que é a nossa última paragem. Zante está localizada na base da colina de Bochali e é simultaneamente a principal cidade e porto da ilha. Após o terramoto que destruiu a cidade em 1953, iniciaram-se os trabalhos de reconstrução e é agora uma cidade moderna que se encontra em contínua expansão no interior. Zakynthos oferece muitas vistas interessantes, tais como a famosa Igreja de Agios Dionysios, a igreja de São Dionysios, bispo de Zante e santo padroeiro da ilha, que alberga as relíquias do santo; os numerosos museus e as características praças da era veneziana de D. Solomos e São Marcos. As vielas minúsculas e silenciosas, as casas antigas com os seus pátios floridos e a paisagem encantadora com vista para a baía da cidade farão do seu passeio um dia único e inesquecível. Partiremos para Bohali, uma bela zona de Zante, mesmo à saída da capital e incluindo as encantadoras aldeias de Akrotiri, Kryoneri e Varres. -

Greece I.H.T

Greece I.H.T. Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) GREECE Visa: Greece is a signatory of the 1995 Schengen Agreement Duty Free: goods permitted: 800 cigarettes or 50 cigars or 100 cigarillos or 250g of tobacco, 1 litre of alcoholic beverage over 22% or 2 litres of wine and liquers, 50g of perfume and 250ml of eau de toilet. Health: a yellow ever vaccination certificate is required from all travellers over 6 months of age coming from infected areas. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS ACHARAVI KERKYRA BEIS BEACH HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63913 (0663) 63991 CENTURY RESORT 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63401-4 (0663) 63405 GELINA VILLAGE 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 64000-7 (0663) 63893 [email protected] IONIAN PRINCESS CLUB-HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63110 (0663) 63111 ADAMAS MILOS CHRONIS HOTEL BUNGALOWS 848 00 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22226, 23123 (0287) 22900 POPI'S HOTEL 848 01 Adamas, on the beach Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22286-7, 22397 (0287) 22396 SANTA MARIA VILLAGE 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22015 (0287) 22880 Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++30 VAMVOUNIS APARTMENTS 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE Greek National Tourism Organisation: Odos Amerikis 2b, 105 64 Athens Tel: TEL: (0287) 23195 (0287) 23398 (1)-322-3111 Fax: (1)-322-2841 E-mail: [email protected] Website: AEGIALI www.araianet.gr LAKKI PENSION 840 08 Aegiali, on the beach Amorgos AEGIALI AMORGOS Capital: Athens Time GMT + 2 GREECE TEL: (0285) 73244 (0285) 73244 Background: Greece achieved its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1829. -

Zakynthos, Ionian Islands

A bit of crystal blue… Zakynthos Zakynthos is an island bursting with things to see, explore and enjoy - from the beautiful beaches, lovely traditional villages, picturesque mountain scenery, watersports, sights such as the Shipwreck and Venetian Castle and as if that wasn't enough there are also several interesting museums; an ideal way to learn more about this wonderful place and its distinguished residents. Zante Vacation Zakynthos is one of the Greek Ionian Islands located off the west coast of the Peloponnese. The island is one of the greenest and most beautiful in the archipelago and boasts some superb sandy beaches. It's the beaches of Zakynthos that make the island a magnet for the package holiday hordes that migrate here between Easter and October. The busiest seaside resorts rival those of Corfu in terms of their frantic nightlife and all-action beach scene. But if you venture further afield than the main resort areas you'll find some lovely secluded coves, dramatic mountain scenery and unspoilt inland villages. The island's mega resort is Laganas on the south coast where 14 kilometers of golden sand gently shelves into shallow water. The main beachfront is chock-a-block with bars, restaurants, hotels and apartment blocks and you'll find all manner of watersports and leisure facilities including ballooning and glass-bottomed boat rides. If you're after 24-hour partying, Brit bars, curries and quiz nights then this is the place for you. You may even find yourself swimming alongside the beautiful loggerhead sea turtles which use the soft sand of the south coast beaches as their nesting grounds. -

A Bit of Crystal Blue… Zakynthos

A bit of crystal blue… Zakynthos Zakynthos is an island bursting with things to see, explore and enjoy - from the beautiful beaches, lovely traditional villages, picturesque mountain scenery, watersports, sights such as the Shipwreck and Venetian Castle and as if that wasn't enough there are also several interesting museums; an ideal way to learn more about this wonderful place and its distinguished residents. Zante Vacation Zakynthos is one of the Greek Ionian Islands located off the west coast of the Peloponnese. The island is one of the greenest and most beautiful in the archipelago and boasts some superb sandy beaches. It's the beaches of Zakynthos that make the island a magnet for the package holiday hordes that migrate here between Easter and October. The busiest seaside resorts rival those of Corfu in terms of their frantic nightlife and all-action beach scene. But if you venture further afield than the main resort areas you'll find some lovely secluded coves, dramatic mountain scenery and unspoilt inland villages. The island's mega resort is Laganas on the south coast where 14 kilometers of golden sand gently shelves into shallow water. The main beachfront is chock-a-block with bars, restaurants, hotels and apartment blocks and you'll find all manner of watersports and leisure facilities including ballooning and glass-bottomed boat rides. If you're after 24-hour partying, Brit bars, curries and quiz nights then this is the place for you. You may even find yourself swimming alongside the beautiful loggerhead sea turtles which use the soft sand of the south coast beaches as their nesting grounds. -

Conservation of Micromeria Browiczii (Lamiaceae), Endemic to Zakynthos Island (Ionian Islands, Greece)

plants Article Conservation of Micromeria browiczii (Lamiaceae), Endemic to Zakynthos Island (Ionian Islands, Greece) Anna-Thalassini Valli 1,*, Christos Chondrogiannis 2, George Grammatikopoulos 2, Gregoris Iatrou 3 and Panayiotis Trigas 1 1 Laboratory of Systematic Botany, Department of Crop Science, School of Plant Sciences, Agricultural University of Athens, Iera Odos 75, 11855 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Plant Physiology, Department of Biology, University of Patras, Rio, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (G.G.) 3 Laboratory of Botany, Department of Biology, University of Patras, Rio, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +306986850009 Abstract: The massive decline in biodiversity due to anthropogenic threats has led to the emergence of conservation as one of the central goals in modern biology. Conservation strategies are urgently needed for addressing the ongoing loss of plant diversity. The Mediterranean basin, and especially the Mediterranean islands, host numerous rare and threatened plants in need of urgent conservation actions. In this study, we assess the current conservation status of Micromeria browiczii, a local endemic to Zakynthos Island (Ionian Islands, Greece), and estimate its future risk of extinction by compiling and assessing scientific information on geographical distribution, population dynamics and repro- ductive biology. The population size and the geographical distribution of the species were monitored for five years. The current population of the species consists of 15 subpopulations. Considerable Citation: Valli, A.-T.; annual fluctuation of population size was detected. The species is assessed as Endangered according Chondrogiannis, C.; to the International Union for Conservation of Nature threat categories. -

1 the Zakynthos Survey 2005 -- Verslag Van De Werkzaamheden En

The Zakynthos Survey 2005 -- Verslag van de werkzaamheden en resultaten Gert Jan van Wijngaarden Het veldwerk binnen het verkennende onderzoek van de Zakynthos Survey 2005 duurde vier weken: maandag 4 juli begon het werk en donderdag 28 juli was de laatste dag in het veld. In deze periode werden vier verschillende typen onderzoek gedaan: extensief inventariserend onderzoek op het gehele eiland, intensieve veldverkenning in verschillende geomorphologische gebieden in het zuidwesten van het eiland, schoonmaak en intensieve survey op de archeologische site van Kalogeras, nabij Vasilikos in het zuidoosten van het eiland en Fysisch geografisch onderzoek. Behalve het veldwerk, zijn er binnen het project ook na de zomer enkele studies verricht zoals het bestuderen van vondsten en het uitwerken van de Fysisch geografische aspecten. Dit heeft geresulteerd in een verslag voor de Griekse archeologische dienst en in een voorlopig rapport dat wordt aangeboden aan Pharos, het wetenschappelijke tijdschrift van het NIA. Foto 1: studenten surveyen op een steile helling nabij Keri Inventariserend onderzoek Bibliografisch onderzoek voorafgaand aan het veldwerk wees op het bestaan van 22 bekende archeologische vindplaatsen buiten de stad Zakynthos. Chronologisch varieerden deze sites van het Paleolithicum (vóór 15.000 v. Chr.) tot aan de Venetiaanse periode (1484-1797 AD). Diverse van deze plekken zijn vele decennia voor het laatst bezocht. De beschikbare topografische informatie stelde ons in staat om 14 van deze plekken te bezoeken. In vijf gevallen kon geen archeologische vindplaats worden vastgesteld, hetzij omdat deze door bouwwerkzaamheden of landbouw vernietigd waren (Alikanas-Akroteri, Vasilikos-Ayios Nikolaos, Vasilikos- Old School and Planos), hetzij omdat bleek dat de archeologische vondsten niet het gevolg waren van antieke bewoning, maar van geomorphologische processen zoals 1 erosie (Ayios Sostis). -

Island Touring

alternative island touring > visiting the greek islands off-the-beaten track Financed by C.I. Leader+, Co-financed by Ministry of Rural Development and Food - European Community EAFFG-G, Development Corporation of Local Authorities of Cyclades S.A., Development Agency of Dodecanese (AN.DO) S.A. 38 IONIAN ISLANDS ZAKYNTHOS luscious mountains characterize the At Keri, on sea rocks, there is the very ZAKYNTHOS eastern part of the island, where the important endemic species of Zakyn- fertile plains lie. In the northwest there thos limonium, but also the mod- are higher mountains, scarce vegeta- est caper (Capparis spinosa), kritamo tion and steep cliffs, that dive vertically (Crithmum maritimum) and thalasso- into the sea and form impressive caves. chorto (Salsola aegea). The scenery is different on the sand Flora dunes of Laganas and Kalamaki where With its Mediterranean sunlight, fre- there are some sand-loving species, such Venetians called it “the Flower of the quent rainfalls and the good “house- as galingale (Cyperus capitatus), Echi- Orient” and modern travellers discover keeping” of its residents, Zakynthos nophora spinosa, Eryngium maritimum, a spot of rare natural beauty and mod- looks like a vast, well-preserved gar- Euphorbia paralias, Juncus acutus, Medi- ern civilisation. den. In the east of the island, one finds cago marina and Pancratium maritimum. The most important marine park of mainly olive tree groves but also citrus, Greece, a cedar forest, sea caves, peach, plum, apricot and pine trees, Fauna breathtaking beaches, horseback rid- numerous palm trees and the famous Except for the famous sea turtle Caret- ing by the sea waves are some of Za- vineyards. -

Utazás a Napfénybe

Utazás a napfénybe ZAKYNTHOSI FAKULTATÍV PROGRAMOK 2020. SMUGGLERS CSEMPÉSZ ÖBÖL – 1 napos A sziget körbehajózása a fővárosból indul, gyönyörködhetünk a sziget szépségében a tenger felől. Kétszeri fürdési lehetőség valamelyik szép öbölben, és egyszer a hajóroncsnál (megfelelő időjárás esetén). Elhaladunk a Banana beach, Agios Nikolaos beach és kápolna, Gerakasi cápaharapás, Peluzo sziget, Marathonisi sziget, Keri félsziget, legnagyobb görög zászló, Mizithres sziklák, Navagio – hajóroncs, Kék barlangok, Agios Nikolaos sziget, Mikro Nisi, Xigiai kénforrások, Alykes/Alykanas, Tsilivi előtt. Indulási napok: kedd és vasárnap Ár: Felnőtt - 30 Euro/fő, Gyerek - 15 Euro/fő (2-14 éves korig) KERI KAIKI TEKNŐSLES Három órás hajókirándulás családias görög hajóval, teknőskeresés, útközben árkádos sziklaszirtek mellett haladunk. Marathonisi szigetnél és a barlangoknál fürdési lehetőség. Indulási napok: kedd és szerda Ár: Felnőtt - 26 Euro/fő, Gyerek – 13 Euro/fő (2-14 éves korig) SZIGETTÚRA AUTÓBUSSZAL - 1 napos Zakynthos sziget megismerése: Bochali kilátó, Macherado, Agia Mavra templom és „kis helyi egyházi múzeum”, borkóstoló egy helyi borászatban, olívaolaj gyárlátogatás, Anafonitria Agios Dionysios kolostor, északi Kék Barlangok, csodás sziklás öblök, Katastari fotóstop, közben üdítő történetek a sziget életéről, mitológiájáról és a helyi szokásokról. Indulási nap: hétfő Ár: Felnőtt – 30 Euro/fő, Gyerek – 15 Euro/fő (2-14 éves korig) Az ár nem tartalmazza az ebédet, és a hajóutat a Kék Barlangokhoz, ami 6 Euro/fő! ZANTE GÖRÖG EST Háromfogásos vacsora, görög táncbemutató és tánctanítás, korlátlan vörös és fehér borfogyasztással Agios Dimitrios falucskában, az ARESTI VILLAS HOTEL csodálatos mediterrán kertjében, egy nemzetközi társasággal, a Fidelity Travel idegenvezetőinek kíséretében. Indulási nap: szerda Ár: Felnőtt - 36 Euro/fő, Gyerek - 18 Euro/fő (2-14 éves korig) Taurus Reisen - A SUNSHINE HOLIDAY GOURP tagja – Cím: 1067 Budapest, Teréz krt. -

Boundless Blue on a Green Background

Boundless blue on a green background THE7 BEST DAYS OF YOUR LIFE Ζakynthos reasons 7TO DISCOVER Zakynthos ü Environment Culture In the emerald waters of the Ionian, at the Today Zakynthos is an ideal destination. ü south-western end of Greece lies Zakyn- It boasts direct flights to and from the thos, land of poets, artists, music and greatest European cities and ferry links to Hospitality song. and from the Peloponnese, Kefalonia and ü Homer calls Zakynthosas «Yliessa», Plin- Italy. ius «Ylidi» and Virgil «Nemorosa», names Its wonderfully warm climate has drawn ü Activities associated with the idyllic beauty of the is- the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) land, its dense forests and verdant nature. to the beaches of Zakynthos, where it lays Zakynthos can offer an enchanting travel its eggs in the golden sand of some of the Gastronomy ü in time for culture lovers, since the island most beautiful beaches of the Mediterra- experienced both the Renaissance and the nean. Recreation Enlightenment. Winters are mild, with high temperatures ü The island has been inhabited since the and great sunshine. Palaeolithic Age and, due to its prominent The long summer of Zakynthos lasts from Beaches geographical location, acted as a cross- May to the end of October. ü roads of East and West and attracted the Heavenly beaches, cosmopolitan enter- ancient Greeks and Romans, the Byzan- tainment, tasty local cuisine, activities, tines, the counts of the Kingdom of Na- fairs and festivals, serenades and archi- ples, the Venetians, the French and the tecture, villages, long walks and discov- English. -

ANNOUNCEMENT Following the Updating Provided to Consumers

ANNOUNCEMENT Following the updating provided to consumers regarding the electricity supply problems caused by Ianos cyclone, HEDNO would like to announce the following: In Kefalonia, the crews continue works and have reconnected the electricity supply for crucial facilities, such as pumping stations, the airport as well as mobile telecommunication antennas at Omala. Moreover, they have reconnected the supply for the areas of Samos, Prokopata and Rozata. In Ithaki, the crews continue the works for the restoration of damages, while the transfer of extra technical staff with vehicles and all necessary equipment is still in progress, because the first morning ferry route from Killini did not take place, which means that the crews had to aboard a different, alternative connection from the port of Patras. The enhanced crew will make every possible effort within the next hours to reconnect the supply for as many areas of the island as possible. In Karditsa, more than 40% of the city has been reconnected to the supply. However, it must be noted that several underground substations of the city remain flooded and this means that apart from pumping the water, extra time is needed for complete drainage before reconnecting electricity. Enhanced technical crews of HEDNO remain in the surrounding areas. In Zakynthos, where a large part of the areas that were afflicted have already been reconnect to electricity supply, works continue for the restoration of damages and their reconnection to the network until the evening, at the areas of Tragaki, Kipseli, Kato, Meso and Ano Gerakario, Agios Dimitrios, Kallithea, Pigadakia, Katastari and Orthonies. Extended nework damages have been detected in the areas of Alikes, Alikanas, Meso and Ano Volima, Anafonitria, Maries and Exohora Kabi. -

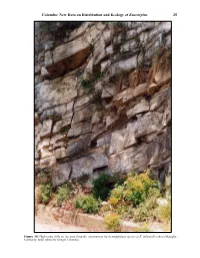

Colombo: New Data on Distribution and Ecology of Euscorpius 25

Colombo: New Data on Distribution and Ecology of Euscorpius 25 Figure 19: High rocky cliffs are the most favorable environment for thermophylous species as E. italicus (Peschiera Maraglio, Lombardy, Italy) (photo by Giorgio Colombo). 26 Euscorpius — 2006, No. 36 Figure 20: E. italicus collecting sites. Emilia Romagna, Lombardy, Marche, Veneto, and Piedmont (Italy): 1. Fermo; 2. Monte Isola; 3. Cislano; 4. Campo; 5. Ceraino; 6. Varallo Pombia; 7. Cernobbio; 8. Isola Comacina; 9. Onno; 10. Cittiglio; 11. Busto Arsizio; 12. Montichiari; 13. Ferrara; 14. Felino; 15. Montechiarugolo; 16. Torrechiara; 17. San Pietro in Cerro; 18. Castell’Arquato. Colombo: New Data on Distribution and Ecology of Euscorpius 27 No. Date Number of specimens, Geographic locality Altitude Comments age and sex a.s.l. 85 24 April E. italicus Peschiera Maraglio surroundings, 190 m In cracks of a high (hot during the day) rocky cliff near the road; 2004 (34 adult males, adult Monte Isola (Brescia), Lombardy, specimens seem to be very active after a short rain, in moderate females, and juveniles) Italy temperature (15°C). Specimens in shallow shelters close the entrance with pedipalps if disturbed (observed with UV light) 108 24 April E. italicus Campo (Verona), 150 m Under the stones on and under stone walls (average humidity) 2005 (2 adult females, 1 adult Veneto, Italy among olive trees and near some abandoned houses, on the path male, 4 subadults and 4 between Castelletto di Brenzone and Campo; a juvenile was juveniles) observed eating a small isopod (sp. indet.) 51 3 May E. italicus near Cislano (Brescia), 650 m In cracks of rocky cliffs near the road, with heat and direct 2003 (1 adult male, 1 adult female, Lombardy,Italy sunlight during the day (observed with UV light) 1 subadult and 1 juvenile) 52 4 May E.