Culture and Climate Change: Recordings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeologist 59

Winter 2006 Number 59 The ARCHAEOLOGIST This issue: ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY Submerged forests from early prehistory p10 Views of a Midlands environmental officer p20 Peatlands in peril p25 Institute of Field Archaeologists SHES, University of Reading, Whiteknights The flora of PO Box 227, Reading RG6 6AB Roman roads, tel 0118 378 6446 towns and fax 0118 378 6448 gardens email [email protected] website www.archaeologists.net p32 ONTENTS .%7 -! IN !RCHAEOLOGICAL &IELD 0RACTICE &ULL AND 0ART TIME $EVELOP YOUR CAREER BY TAKING A POSTGRADUATE DEGREE IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE C 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS LAUNCHING AN EXCITING AND UNIQUE COURSE WHICH SEEKS TO BRIDGE THE GAP BETWEEN THEORY AND PRACTICE )T COMBINES A CRITICAL AND EVALUATIVE APPROACH TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION WITH PRACTICAL SKILLS AND TECHNICAL EXPERTISE4AUGHT THROUGH CLASSROOM AND FIELDWORK BASED SESSIONS A PLACEMENT WITHIN THE PROFESSION 1 Contents AND A DISSERTATION ITS EMPHASIS IS UPON FOSTERING A NEW CRITICALLY INFORMED APPROACH TO THE PROFESSION 2 Editorial 4HE 5NIVERSITY OF -ANCHESTER IS AN INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNISED CENTRE FOR SOCIAL ARCHAEOLOGY /UR RESEARCH 3 From the Finds Tray THEMES INCLUDE POWER AND IDENTITY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND MONUMENTALITY HERITAGE AND CONTEMPORARY 5 Finishing someone else’s story Michael Heaton, Peter Hinton and Frank Meddens SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PAST RITUAL AND RELIGION THEORY PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE OF ARCHAEOLOGY7E ARE A COHERENT 6 IFA and Continuous Professional Development Kate Geary AND FRIENDLY COMMUNITY WITH AN -

The Hartwell Paper a New Direction for Climate Policy After the Crash of 2009

The Hartwell Paper A new direction for climate policy after the crash of 2009 Hartwell House, Buckinghamshire, where the co-authors conceived this paper, 2-4 February 2010 May 2010 22th April 2010 THE HARTWELL PAPER: FINAL TEXT EMBARGOED UNTIL 11 MAY 2010 0600 BST The co-authors Professor Gwyn Prins, Mackinder Programme for the Study of Long Wave Events, London School of Economics & Political Science, England Isabel Galiana, Department of Economics & GEC3, McGill University, Canada Professor Christopher Green, Department of Economics, McGill University, Canada Dr Reiner Grundmann, School of Languages & Social Sciences, Aston University, England Professor Mike Hulme, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, England Professor Atte Korhola, Department of Environmental Sciences/ Division of Environmental Change and Policy, University of Helsinki, Finland Professor Frank Laird, Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, USA Ted Nordhaus, The Breakthrough Institute, Oakland, California, USA Professor Roger Pielke Jnr, Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado, USA Professor Steve Rayner, Institute for Science, Innovation and Society, University of Oxford, England Professor Daniel Sarewitz, Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes, Arizona State University, USA Michael Shellenberger, The Breakthrough Institute, Oakland, California, USA Professor Nico Stehr, Karl Mannheim Chair for Cultural Studies, Zeppelin University, Germany Hiroyuki Tezuka , General Manager, Climate -

International Initiatives to Address Tropical Timber Logging and Trade

International Initiatives to Address Tropical Timber Logging and Trade A Report for the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment Lars H. Gulbrandsen and David Humphreys FNI Report 4/2006 International Initiatives to Address Tropical Timber Logging and Trade A Report for the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment Lars H. Gulbrandsen The Fridtjof Nansen Institute Norway [email protected] David Humphreys Open University UK April 2006 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Copyright © The Fridtjof Nansen Institute 2006 Title International Initiatives to Address Tropical Timber Logging and Trade. A Report for the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment. Publication Type and Number Pages FNI report 4/2006 67 Authors ISBN Lars H. Gulbrandsen and David Humphreys 82-7613-489-0 Programme or Project ISSN 653 0801-2431 Abstract This report examines a broad range of international initiatives to address tropical timber logging and trade. The report first looks at international and regional initiatives to control illegal logging, with a particular focus on the Forest Law Enforcement and Governance (FLEG) processes in East Asia and the Pacific, Africa, and Europe and North Asia. Second, the report reviews the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) action plan, which includes voluntary partnership agreements between producer countries and the EU on timber licensing; the adoption by member states of procurement policies stipulating the purchase of timber from legal sources; promoting private sector initiatives, including codes of conduct; and the exercise of due diligence by export credit agencies and financial institutions when funding logging pro- jects. Third, the report examines various forest certification schemes and inter- national discussions about forest certification in some detail, because several governments have identified certification as a way of verifying that public pro- curement requirements for legal and sustainable timber are met. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

The Fumarolic CO Output from Pico Do Fogo Volcano

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 139, No. 3 (2020), pp. 325-340, 9 figs., 3 tabs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.03) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2020 The fumarolic CO2 output from Pico do Fogo Volcano (Cape Verde) ALESSANDRO AIUPPA (1), MARCELLO BITETTO (1), ANDREA L. RIZZO (2), FATIMA VIVEIROS (3), PATRICK ALLARD (4), MARIA LUCE FREZZOTTI (5), VIRGINIA VALENTI (5) & VITTORIO ZANON (3, 4) ABSTRACT output started early back in the 1990s (e.g., GERLACH, 1991), The Pico do Fogo volcano, in the Cape Verde Archipelago off substantial budget refinements have only recently arisen the western coasts of Africa, has been the most active volcano in the from the 8-years (2011-2019) DECADE (Deep Earth Carbon Macaronesia region in the Central Atlantic, with at least 27 eruptions Degassing; https://deepcarboncycle.org/about-decade) during the last 500 years. Between eruptions fumarolic activity has research program of the Deep Carbon Observatory (https:// been persisting in its summit crater, but limited information exists for the chemistry and output of these gas emissions. Here, we use the deepcarbon.net/project/decade#Overview) (FISCHER, 2013; results acquired during a field survey in February 2019 to quantify FISCHER et alii, 2019). the quiescent summit fumaroles’ volatile output for the first time. By One key result of DECADE-funded research has been combining measurements of the fumarole compositions (using both a the recognition that the global CO2 output from subaerial portable Multi-GAS and direct sampling of the hottest fumarole) and volcanism is predominantly sourced from a relatively of the SO2 flux (using near-vent UV Camera recording), we quantify small number of strongly degassing volcanoes. -

Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and More on the Lost Comic

‘He was basically the funniest person I ever met’ Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and more on the lost comic genius of Harris Wittels By Hadley Freeman Monday 17.04.17 12A Quiz Fingersh Pit your wits against the breakout stars of this year’s University Challenge, and Bobby Seagull , with Eric Monkman 20 questions set by the brainy duo. No conferring The Fields Medal has in secutive order. This spells out the 5 1 recent times been awarded name of which London borough? to its fi rst woman, Maryam Mirzakhani in 2014, and was What links these former infamously rejected by Russian 7 prime minsters: the British Grigori Perelman in 2006. Which Spencer Perceval, the Lebanese academic discipline is this prize Rafi c Hariri and the Indian awarded for? Indira Gandhi? Whose art exhibition at Tate Narnia author CS Lewis, 2 Britain this year has become 8 Brave New World author the fastest selling show in the Aldous Huxley and former US gallery’s history? president John F Kennedy all died on 22 November. Which year The fi rst national park desig- was this? 3 nated in the UK was the Peak District in 1951. Announced as a Which north European national park in 2009 and formed 9 country’s fl ag is the oldest in 2010, which is the latest existing fl ag in the world? It is English addition to this list? 15 supposed to have fallen out of the heavens during a battle in the University Challenge inspired 13th century. 4 the novel Starter for Ten. -

Download the Program of Events

PUBLIC PROGRAMS F N O L U A Cultural Response to Climate Change September 30–December 15, 2011 All events take place in the gallery unless otherwise indicated. Sheila C. Johnson Design Center Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery Parsons The New School for Design 2 W. 13 Street, Ground Floor Open daily 12:00–6:00 p.m. and D until 8:00 p.m. on Thursdays Admission is free www.newschool.edu/sjdc INTRODUCTION CONTENTS These days, breezy conversations by the dating play. We’ll look at climate change in PANELS & CONVERSATIONS elevator about the weather soon dip into cities across the world as well as what could doldrums of worry about climate. It’s raining happen on our own Gowanus. We’ll learn Conversation with the Curators: David Buckland and Chris Wainwright 2 again and it’s been a sodden summer. We about Asia’s mega-deltas, everyday religion What Ifs: Climate Change and Creative Agency 2 find we know what flood zone we live in. and climate change in the Himalayas, the Climate Change: Art, Activism, and Research 4 Upstate farms have been ravaged, making waterlines of Venice, and Antarctica. We’ll Under Water: Climate Change, Insurance Risk, and New York Real Estate 5 our neighborhood greenmarkets places of listen to a musical performance of this What Insects Tell Us: A Conversation between David Dunn and Hugh Raffles 5 strange melancholy. We’re anxious about our clement world and also to what insects tell us. Southern Discomforts: A Focus on Antarctica 6 tap water and perplexed by spurious choices Students are invited to participate in a video between clean energy and clean water. -

Ed Reardon Download Mp3

Ed reardon download mp3 CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Meet Ed Reardon, author, pipe smoker, consummate fare-dodger and master of the abusive email, trying to survive in a world where the media seems to be run by idiots and charlatans. Available episodes of Ed Reardon's Week. There are currently no available episodes. Related Content. Ed Reardon (played by Christopher Douglas) is a failed writer, fare-dodger and master of the abusive email. Living with his cat in a one-bedroom flat, this bearded divorcee grumbles at a modern world seemingly run by year-olds, while churning out books such as Jane Seymour's Household Hints and Pet Peeves (to pay the bills) and trying to Reviews: Ed Reardon (played by Christopher Douglas) is a failed writer, fare-dodger and master of the abusive email. Living with his cat in a one-bedroom flat, this bearded divorcee grumbles at a modern world seemingly run by year- olds, while churning out books such as Jane Seymour's Household Hints and Pet Peeves (to pay the bills) and trying to live off the royalties of his episode of Tenko. Ed Reardon, author, pipe smoker, consummate fare-dodger and master of the abusive email, attempts to survive in a world where the media seems to be run by idiots and lying charlatans. In these six episodes, Ed and Mary Potter are in a record breaking second month of partnership 'bliss'. But work isn. Сервис электронных книг ЛитРес предлагает скачать аудиокнигу Ed Reardon's Week The Complete Seventh Series, Andrew Nickolds в формате mp3 или слушать онлайн! Скачивайте и слушайте лучшие аудиокниги. -

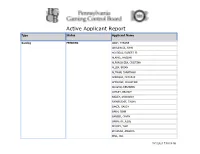

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Facing Our Future

ABOUT THE COVER ART Get ready for the end of our world as we know it. How can we not despair at such a prospect? Roll up the sleeves on imagination, compassion, and science and let’s get ready for our new world. The poster for Gustavus Adolphus College’s Nobel Conference “Climate Changed” illustrates some of the solutions for living in a changed climate, as well as the attendant reality of mass migrations. Sharon Stevenson, Designer CLIMATE CHANGEDFACING OUR FUTURE 800 West College Avenue | Saint Peter, MN 56082 | gustavus.edu/nobelconference NOBEL CONFERENCE 55 | SEPTEMBER 24 & 25, 2019 | GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS COLLEGE NOBEL CONFERENCE 55 I love being in nature, whether it is time at our family cabin WELCOin northern Minnesota, a walk in the Linnaeus Arboretum at ME Gustavus, or the trip I took this summer with my husband to camp and hike in the western national parks. Like many people, I find nature to be a source of renewal, a connection to the Earth and the Divine, and a reminder of the interconnectedness of creation. Also, like many people, I am concerned about our world. As scientific evidence of human-caused climate change is mounting, members of the Gustavus community are working to understand this crisis and its local and Alfred Nobel had a vision of global effects. On campus, several groups are working on this great challenge a better world. He believed of our time. For example, the President’s Environmental Sustainability Council that people were capable of and the student-led Environmental Action Coalition are leading campus initiatives to reduce our helping to improve society campus energy use by 25 percent in the next five years and make improvements in recycling and through knowledge, science, and waste management with the goal of becoming a zero-waste campus, with 90 percent of solid waste humanism. -

Turbulent World: an Artwork Indicating the Impact of Climate Change

Turbulent World: An Artwork Indicating the Impact of Climate Change Angus Graeme Forbes∗ Electronic Visualization Laboratory University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL, USA [email protected] Abstract New World.” In their call for entries, they asked artists to think about creative responses to climate change: “What is This paper describes an artwork created in response to a ques- the role of the artist as citizen in this climate? How might we tion about the role of the artist in communicating climate reclaim our choice, our connection, our social power when change issues. The artwork, titled Turbulent World, incorpo- 1 rates turbulence and surprise as a means to visualize the po- immersed in a deteriorating environment?” Turbulent World tential instability of our culture and the environment due to was originally featured in this show, presented within the climatic changes indicated by increased worldwide tempera- Spare Change Artist Space in downtown San Francisco. It tures. The artwork makes use of a custom fluid engine that can was installed for the duration of the exhibition, which ran represent any amount of turbulence and energy. A dataset en- from late 2013 through early 2014. coding a simulation of rising surface-air temperatures over the The goal of Turbulent World is to provide insight into a next century is mapped to the turbulence system; and the visu- data model that represents current thinking by leading sci- alization is updated as the months and years flow by, based on entists about climate change. Scientific visualization often the projected temperatures at different areas of the world. -

Jarred Christmas

Jarred Christmas COMEDIAN, WRITER, TV & RADIO PRESENTER, IMPROVISER AND ACTOR ‘BEST CHILDREN’S SHOW’ NOMINEE – LEICESTER COMEDY FESTIVAL 2017 ‘BEST COMPERE’ - CHORTLE AWARDS 2016 New Zealand Sensation Jarred Christmas is one of the most innovative and exciting stand-ups on the UK circuit. A sought-after headliner famed for his quick-witted spontaneity, masterful skills of improvisation and energetic storytelling; Jarred is a regular at the Edinburgh Festival, and at comedy clubs and International festivals around the globe. He is a regular team member at The Comedy Store’s weekly topical show The Cutting Edge and was recently named Best Compere at the 2016 Chortle Awards; scooping the title for the second time. A dynamic onstage persona combined with the ability to improvise with anything that’s thrown his way makes Jarred’s comedy sizzle with originality. Early in his career he supported both Ross Noble and Tommy Tiernan on UK tours. He has since written and performed in countless shows at the Edinburgh Festival and has toured the UK in his own right with his solo shows Jarred Christmas Stands Up and Let’s Go Mofo. He is currently playing to packed theatres across the UK hosting the All Star Stand Up Tour. The show features a world-class line-up of comedians and Jarred is honoured to be hosting the show for the second year running. Combining his superlative improv and stand-up comedy skills (not to mention vocal agility), Jarred has recently developed The Mighty Beatbox Gameshow and a child-friendly version The Mighty Kids Beatbox Gameshow which he hosts alongside acclaimed beatboxer The Hobbit.