WIM Pre Reading Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plays and Pinot: Bedroom Farce

Plays and Pinot: Bedroom Farce Synopsis Trevor and Susannah, whose marriage is on the rocks, inflict their miseries on their nearest and dearest: three couples whose own relationships are tenuous at best. Taking place sequentially in the three beleaguered couples’ bedrooms during one endless Saturday night of co-dependence and dysfunction, beds, tempers, and domestic order are ruffled, leading all the players to a hilariously touching epiphany. About the Playwright Alan Ayckbourn, in full Sir Alan Ayckbourn, (born April 12, 1939, London, England), is a successful and prolific British playwright, whose works—mostly farces and comedies—deal with marital and class conflicts and point out the fears and weaknesses of the English lower-middle class. He wrote more than 80 plays and other entertainments, most of which were first staged at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough, Yorkshire, England. At age 15 Ayckbourn acted in school productions of William Shakespeare, and he began his professional acting career with the Stephen Joseph Company in Scarborough. When Ayckbourn wanted better roles to play, Joseph told him to write a part for himself in a play that the company would mount if it had merit. Ayckbourn produced his earliest plays in 1959–61 under the pseudonym Roland Allen. His plays—many of which were performed years before they were published—included Relatively Speaking (1968), Mixed Doubles: An Entertainment on Marriage (1970), How the Other Half Loves (1971), the trilogy The Norman Conquests (1973), Absurd Person Singular (1974), Intimate Exchanges (1985), Mr. A’s Amazing Maze Plays (1989), Body Language (1990), Invisible Friends (1991), Communicating Doors (1995), Comic Potential (1999), The Boy Who Fell into a Book (2000), and the trilogy Damsels in Distress (2002). -

List of Play Sets

Oxfordshire County Council List of Play Sets Available from the Oxford Central Library 2015 Oxford Central Library – W e s t g a t e – O x f o r d – O X 1 1 D J Author Title ISBN Copies Cast Genre Russell, Willy Shirley Valentine: A play T000020903 2 1f Comedy (Dramatic) Churchill, Caryl Drunk enough to say I love you? T000096352 3 2m Short Play, Drama Churchill, Caryl Number T000026201 3 2m Drama Fourie, Charles J. Parrot woman T000037314 3 1m, 1f Harris, Richard The business of murder T000348605 3 2m, 1f Mystery/Thriller Pinter, Harold The dumb waiter: a play T000029001 3 2m Short Play Plowman, Gillian Window cleaner: a play T000030648 3 1m, 1f Short Play Russell, Willy Educating Rita T000026217 3 1m, 1f Comedy (Dramatic) Russell, Willy Educating Rita T000026217 3 Simon, Neil They're playing our song T000024099 3 1m, 1f Musical; Comedy Tristram, David Inspector Drake and the Black Widow: a comedy T000035350 3 2m, 1f Comedy Ayckbourn, A., and others Mixed doubles: An entertainment on marriage T000963427 4 2m, 1f Anthology Ayckbourn, Alan Snake in the grass: a play T000026203 4 3f Drama Bennett, Alan Green forms (from Office suite) N000384797 4 1m, 2f Short Play; Comedy Brittney, Lynn Ask the family: a one act play T000035640 4 2m, 1f Short Play; Period (1910s) Author Title ISBN Copies Cast Genre Brittney, Lynn Different way to die: a one act play T000035647 4 2m, 2f Short Play Camoletti, Marc; Happy birthday 0573111723 4 2m, 3f Adaptation; Comedy Cross, Beverley Chappell, Eric Passing Strangers: a comedy T000348606 4 2m, 2f Comedy (Romantic) -

Alan Ayckbourn: Complete Play List

Alan Ayckbourn - Complete Writing Credit: Alan Ayckbourn’s Official Website www.alanayckbourn.net License: This resource is available for free reproduction providing it is credited, is not used for commercial purposes and has not been modified without permission. Full Length Plays 1959 The Square Cat 1959 Love After All 1960 Dad’s Tale 1961 Standing Room Only 1962 Christmas V Mastermind 1963 Mr Whatnot 1965 Meet My Father subsequently Relatively Speaking (revised) 1967 The Sparrow 1969 How The Other Half Loves 1970 The Story So Far… subsequently Me Times Me Time Me (revised) subsequently Me Times Me (revised) subsequently Family Circles (revised) 1971 Time And Time Again 1972 Absurd Person Singular 1973 The Norman Conquests comprising Fancy Meeting You subsequently Table Manners Make Yourself At Home subsequently Living Together Round And Round The Garden 1974 Absent Friends 1974 Confusions 1975 Jeeves (with Andrew Lloyd Webber) subsequently By Jeeves (with Andrew Lloyd Webber) (revised) 1975 Bedroom Farce 1976 Just Between Ourselves 1977 Ten Times Table 1978 Joking Apart 1979 Sisterly Feelings 1979 Taking Steps 1980 Suburban Strains (with Paul Todd) 1980 Season’s Greetings 1981 Way Upstream 1981 Making Tracks (with Paul Todd) 1982 Intimate Exchanges comprising Events On A Hotel Terrace Affairs In A Tent Love In The Mist A Cricket Match A Game Of Golf A Pageant A Garden Fete A One Man Protest 1983 It Could Be Any One Of Us subsequently It Could Be Any One Of Us (revised) 1984 A Chorus Of Disapproval 1985 Woman In Mind 1987 A Small Family Business 1987 Henceforward… 1988 Man Of The Moment 1988 Mr. -

PENELOPE KEITH and TAMMY GRIMES Are the Society's Newest

FREE TO MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY APRIL 2008 - THE NEWSLETTERCHAT OF THE NOËL COWARD SOCIETY Price £2 ($4) President: HRH Duke of Kent Vice Presidents: Barry Day OBE • Stephen Fry • Penelope Keith CBE • Tammy Grimes PENELOPE KEITH and TAMMY GRIMES are the Society’s Newest Vice Presidents arbara Longford, the Society’s Chairman, was delighted to announce this month that the star of the West End Coward revivals Star Quality and Blithe Spirit, Penelope Keith, has agreed to become our next Vice President. In America the actress Tammy Grimes the star of Look After Lulu, High Spirits and Private LivesBhas also graciously accepted our invitation. Both are known Coward devotees and will provide a strong theatrical presence amongst the Society’s Honorary Officers. Penelope Keith is best known in the UK for her television appearances in two of the most successful situation comedies in entertainment history. She made her first mark as the aspiring upper-class neighbour, Margot Ledbetter, in The Good Life and later as the upper-class lady fallen on hard times, Audrey Fforbes-Hamilton, in To The Manor Born. Apart from Star Quality and Blithe Spirit she has appeared on stage at the Chichester Festival in the premiere of Richard Everett’s comedy Entertaining Angels, which she later took on tour. In 2007 she played the part of Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest on tour and is currently appearing in the same role at the Vaudeville Theatre in the West End (booking until 26 April). Her best known theatre appearance was in 1974, playing Sarah in The Norman Conquests opposite her The Good Life co-star Richard Briers. -

Other Half PR

CONTACT: Nancy Richards – 917-873-6389 (cell) /[email protected] MEDIA PAGE: www.northcoastrep.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE: NORTH COAST REP SERVES UP BANQUET OF FUN IN HOW THE OTHER HALF LOVES By Sir Alan Ayckbourn Performances Beginning Wednesday, April 11, 2018 Running Through Sunday, May 6, 2018 Now extended by popular demand to May 13, 2018 Directed by Geoffrey Sherman Solana Beach, CA Britain’s comic genius, Sir Alan Ayckbourn, has penned a fast-paced and hilariously funny theatrical feast that stands as a classic modern comedy. With the precision of a master chef, Sir Ayckbourn mixes three very different marriages into a pot, simmering with sex, jealousy, and liberally spiced with ingenious stagecraft. Full of clever, razor-sharp dialogue and impeccable split-second timing, HOW THE OTHER HALF LOVES is a treat you won’t want to miss. Find out why The London Daily Mail called this “a delicious, jolly good show.” Geoffrey Sherman directs Jacqueline Ritz,* James Newcomb,* Sharon Rietkerk,* Christopher M. Williams,* Noelle Marion,* and Benjamin Cole. The design team includes Marty Burnett (Scenic Design), Matthew Novotny (Lighting Design), Aaron Rumley (Sound), Elisa Benzoni (Costumes), and Holly Gillard (Prop Design). Cindy Rumley* is the Stage Manager. *The actor or stage manager appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional actors and stage managers in the United States. For background information and photos, go to www.northcoastrep.org/press. HOW THE OTHER HALF LOVES previews begin Wednesday, April 11. Opening Night on Saturday, April 14, at 8pm. There will be a special talkback on Friday, April 20, with the cast and artistic director. -

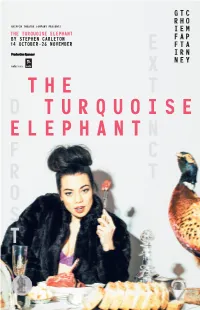

The Turquoise Elephant E X T D N F C R T O

GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT STEPHEN CARLETON BY STEPHEN CARLETON 14 OCTOBER-26 NOVEMBER E Production Sponsor Meet Augusta Macquarie: Her Excellency, patron of the arts, X formidable matriarch, environmental vandal. THE T D TURQUOISE Inside her triple-glazed compound, Augusta shields herself from the catastrophic elements, bathing in THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT the classics and campaigning for the reinstatement of global reliance on fossil fuels. Outside, the world lurches from one environmental cataclysm to the next. ELEPHANT N Meanwhile, her sister, Olympia, thinks the best way to save endangered species is to eat them. Their niece, Basra, is intent on making a difference – but how? Can you save the world one blog at a time? F C Stephen Carleton’s shockingly black, black, black political farce won the 2015 Griffin Award. R T It’s urgent, contemporary and perilously close to being real. Director Gale Edwards brings her magic and wry insight to the world premiere of this very funny, clever and wicked new work. O S T CURRENCY PRESS GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT BY STEPHEN CARLETON 14 OCTOBER-26 NOVEMBER Director Gale Edwards Set Designer Brian Thomson Costume Designer Emma Vine Lighting and AV Designer Verity Hampson Sound Designer Jeremy Silver Associate Lighting Designer Daniel Barber Stage Manager Karina McKenzie Videographer Xanon Murphy With Catherine Davies, Maggie Dence, Julian Garner, Belinda Giblin, Olivia Rose, iOTA SBW STABLES THEATRE 14 OCTOBER - 26 NOVEMBER Production Sponsor Government Partners Griffin acknowledges the generosity of the Seaborn, Broughton and Walford Foundation in allowing it the use of the SBW Stables Theatre rent free, less outgoings, since 1986. -

Ayckbourn's Stage Reaction to Families Buried In

AYCKBOURN’S STAGE REACTION TO FAMILIES BURIED IN TECHNOLOGY KAĞAN KAYA Cumhuriyet University, Sivas Abstract: The paper analyses the premature warnings of British playwright, Alan Ayckbourn, who foresees that the modern family has been under the onslaught of technology. His dystopia, Henceforward... (1987) , set in the flat of the high-tech addict protagonist, Jerome, tells one of the traditional family stories of the playwright. However, the paper focuses on Ayckbourn’s neglected dramatic mission - that of securing the British family. Keywords: Alan Ayckbourn, British drama, dystopia, family, technology “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” (Tolstoy (2001), 1875-1877:1) 1. Introduction British playwright, Sir Alan Ayckbourn, is often referred to as a famous farceur. However, he is not pleased with this label, because with a “tireless dedication to the idea of theatre and... fierce moral concern with the state of the nation,” (Billington 1989), he has a distinctive multi-dimensional understanding of drama. In fact, he expresses sociologically harsh criticism of British middle-class man through his black comedy, in the light of his vision of drama. Henceforward... , which is the thirty-fourth play of the playwright, is a very noteworthy fraction of Ayckbourn’s tenet, for several reasons. It received the Evening Standard Award for Best Comedy in 1989. It was the second quickest transfer of all Alan Ayckbourn plays to the US, Houston’s Alley Theatre. Even the title of the play suggests a kind of manifesto of the playwright which declares that he is resolute in the changes of his drama. -

House & Garden

2008-2009 SEASON / WELCOME TO C T3 PEOPLE HOUSE & GARDEN A couple of months ago I had asked Jae Alder, BOARD OF DIRECTORS 'Hey! Who's directing House and Garden?' He CHAIRSonja J. McGill LIAISON, CITY OF DALLAS CULTURAL COMMISSION looked at me fora full fiveseconds, and then he TailimSong said 'Um ....You are.' BOARD MEMBERS JacAlder, Nancy Cochran, Roland ll[VirginiaDykes, David G. Luther, Patsy Here are the reasons I didn't completely freakout. P. Yung Micale, Jean M. Nelson,Shanna Nugent, It's all about trust. Valerie W. Pelan, Eileen Rosenblum, PhD, Enika 1) I trust myself Anybody that knows Eves = Absurd Person Sh1gular - that sort Schulze, John & Bonnie Strauss, AnnStuart, PhD, Katherine Ward, Karen Washington, Linda R. me knows I am constantly working on of thing. So I figure he has this whole Zimmerman multiple projects at the same time. I 'being in two places at one time' concept HONORARY BOARD MEMBERS GaryW. Grubbs, do this because I have artistic needs. down cold. And if you are going to trust Elizabeth Rivera, JanetSpencer Shaw Like paying my rent. So directing what anybody to do their homework and CORPORATE ADVISORY COUNCIL amounts to two full length productions get the mechanics of a tricky conceit TNS PARTNERS Jim Chambers simultaneously? A walk in the park ... like this worked out, it's going to be ALLIE BETH ALLMAN &ASSOCIATES Ayckbourn. I knew I could trust this Bill & MarsueWilliams 2) I trust Jae. He is my mentor. He GABLES RESIDENTIAL Cindy Davis whole schlemeil to work. And it does. usually knows how to match up a HEALTH SEARCH, LLC Dodie Butler A Class Act Thank God. -

Mother Goose by Damian Trasler, David Lovesy, Steve Clark and Brian Two - TLC Creative

THE WORTHY PLAYERS AMATEUR DRAMATIC SOCIETY presents THE WORTHYS JUBILEE HALL, KINGS WORTHY 2nd, 3rd, 9th, 10th December 2016 - 7.30pm 3rd, 10th December 2016 - 2.30 pm Mother Goose By Damian Trasler, David Lovesy, Steve Clark and Brian Two - TLC Creative A word from the Director Miriam Edmond I became involved with the Worthy Players in 1993 singing and dancing in music hall each year, having never been near a stage before. I had my first part in a pantomime with ‘Panto Trek’ and then went on to enjoy acting in ‘Outside Edge’ and ‘Visiting Hour’, but it was in 2001, I first played the piano accompaniment for Dick Whittington, after our resident pianist moved away. Since then I have continued to provide the music for pantomime most years. I took the decision this year to have a go at directing for the first time, but could not have achieved this without the solid support of Martin and Nick, both of whom have lent their experience and knowledge every step of the way. I also want to thank David and Alison Woolford who helped hugely before setting off on their travels, Shirley for the wonderful costumes and Richard and David for the sound and lights. As for the cast, they have been truly fantastic, having contributed their ideas and skills and in some cases suddenly taking on more than they thought. It has been a real team effort! I hope you have as much fun watching ‘Mother Goose’ as we have had in the making and performing of it. -

Relatively Speaking

39th Season • 379th Production JULIANNE ARGYROS STAGE / MARCH 18 THROUGH APRIL 6, 2003 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents RELATIVELY SPEAKING by ALAN AYCKBOURN Scenic and Costume Design Lighting Design Production Manager Stage Manager NEPHELIE ANDONYADIS LONNIE ALCARAZ JEFF GIFFORD *JAMIE A. TUCKER Directed by DAVID EMMES Honorary Producers SUE AND RALPH STERN Presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. Relatively Speaking • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Greg ...................................................................................... *Douglas Weston Ginny .................................................................................... *Jennifer Dundas Philip ........................................................................................ *Richard Doyle Sheila .................................................................................... *Linda Gehringer SETTING Apartment in London and the English countryside. LENGTH Approximately two hours and 10 minutes with one intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting Director ................................................................................. Joanne DeNaut Dramaturg ................................................................................. Linda Sullivan Baity Production Assistant .......................................................................... Christi Vadovic Dialect Consultant .......................................................................... -

The Alan Ayckbourn and Andrew Lloyd Webber Musical Based on the Jeeves Stories by P.G

SPOTLIGHT ON THEATER NOTES PRODUCED BY THE PERFORMANCE PLUS™ PROGRAM, KENNEDY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT THE ALAN AYCKBOURN AND ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER MUSICAL BASED ON THE JEEVES STORIES BY P.G. WODEHOUSE logo designed by Dewynters plc., London TM © 1996 RUG Ltd. TM © 1996 RUG London plc., Dewynters designed by logo Y EEVES “The Fairy Tale World B J Jeevesorever joined and at the comic Bertie hip, Reginald Jeeves and Bertram Wilberforce Wooster are in the front rank of Fdroll characters invented in the 20th century. of P.G.odehouse Wodehouse” biographer Richard Jeeves is the perfect manservant. Bertie (“Bertram Voorhees* points out that BERTheTIE WOO STCharactersER TheTHE SCENE Story: A church hall, later to represent a London Wilberforce” is reserved for the rarest of occasions) is the WWodehouse’s fiction belongs “spiri- John Scherer flat and the house and grounds of Totleigh Towers. far-from-perfect master. Through the imagination of P.G. tually to the world of Victoria and Edward VII,” a THE TIME: This very evening. Wodehouse they have found a happy symbiosis, not unlike world “roughly limited on one side by the EEVES his manservant J , Eager to contribute to the festivities of a charity benefit that of naughty child and protective parent. Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria [1897] and Richard Kline performance in an English village hall, dim-but-affable Given Bertie’s propensity for foolish capers and his limited on the other by the introduction of the cross- Bertie Wooster bursts on stage strumming a frying pan. HONORIA GLOSSOP, his ex-fiance vocabulary, it is a bit difficult to understand how he managed word puzzle [1925].” To his confusion and chagrin, he realizes that the pan has Donna Lynne Champlin to graduate such prestigious institutions of learning as Eton been substituted for his stolen banjo. -

A Technician in the Wings: Ayckbourn's Comic Potential Stephanie Tucker

Spring 2003 71 A Technician in the Wings: Ayckbourn's Comic Potential Stephanie Tucker Alan Ayckboum has spent his entire professional life in the theater. Before becoming a director and playwright, he worked as "a stage manager, sound technician, lighting technician, scene painter, prop-maker and actor."^ He wrote his first play at 20, encouraged by his mentor Stephen Joseph, who, in response to Ayckboum's distaste for the role of Nicky in John van Druten's Bell Book and Candle, suggested that the young actor write himself a promising part. So he did—Jerry Wattis in The Square Cat "It was a piece of wish-fulfillment for the lad who fancied being a rock star—a central role for himself in which he got to dress up in glitzy teddy-boy drapes and play (very badly, apparently!) rock 'n' roll guitar."^ A dream, realized by an actor, in a fiction he had created! Boundaries between life and art had already begun to blur. That was in 1959. Since then Ayckboum has written sixty-one^ more plays, including two trilogies, a dramatic diptych, and several musicals. Because his plays are commercially successful, his subject matter the trials and woes of the middle classes, his genre of choice comedy-cum-farce, the playwright was initially perceived "as the inheritor of the lightweight boulevardier mantle recently worn by Terence Rattigan, Peter Ustinov and Enid Bagnold'"^—and, as such, dismissed as a minor if prodigiously productive playwright. According to Michael Billington, this critical prejudice has persisted, at least until 1990: "Alan Ayckboum is popular.