Report on an Unannounced Inspection HMYOI Glen Parva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE for Information Only

DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE For Information Only APPROVALS ISSUED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1178/FUL Mr O Griffiths Countesthorpe Parish Land Off Regent Road Countesthorpe Council Erection of three storey detached building comprising 3 no. one bedroom apartments and 1 no. two bedroomed apartments. Associated car parking and amenity space. Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1179/LBC Mrs Sue Ward Kirby Muxloe Parish 77 Main Street Kirby Muxloe Leicestershire Council Installation of a replacement front door Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1220/DOC Cadeby Homes Enderby Parish Council Land Off Harolds Lane Enderby Discharge of condition 6 (landscaping) attached to planning permission 13/0301/1/PX. Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1264/HH Mr And Mrs J. Collingridge Narborough Parish Council 1 Coventry Road Narborough Leicestershire Demolition of existing garage, proposed erection of new garage and alterations to adjoining wall. Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1329/FUL Mr J Mac Sapcote Parish Council Land To South East Of Granitethorpe Quarry Leicester Road Sapcote Erection of stables, creation of manege and hard standing (Revised Scheme) Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1362/FUL Mr Oliver Pickering Blaby Parish Council 28 Park Road Blaby Leicestershire Detached double garage to rear Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/1376/HH Mr P Cudbill Glenfield Parish Council 2 Gallimore Close Glenfield Leicestershire Two storey side extension and retention of boundary wall and gate at the front of the property. -

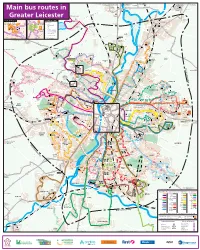

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Breakdown of COVID-19 Cases in Leicestershire

Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 11/08/2021 This report summarises the information from the surveillance system which is used to monitor the cases of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Leicestershire. The report is based on daily data up to 11th August 2021. The maps presented in the report examine counts and rates of COVID-19 at Middle Super Output Area. Middle Layer Super Output Areas (MSOAs) are a census based geography used in the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales. The minimum population is 5,000 and the average is 7,200. Disclosure control rules have been applied to all figures not currently in the public domain. Counts between 1 to 5 have been suppressed at MSOA level. An additional dashboard examining weekly counts of COVID-19 cases by Middle Super Output Area in Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland can be accessed via the following link: https://public.tableau.com/profile/r.i.team.leicestershire.county.council#!/vizhome/COVID-19PHEWeeklyCases/WeeklyCOVID- 19byMSOA Data has been sourced from Public Health England. The report has been complied by Strategic Business Intelligence in Leicestershire County Council. Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 11/08/2021 Breakdown of testing by Pillars of the UK Government’s COVID-19 testing programme: Pillar 1 + 2 Pillar 1 Pillar 2 combined data from both Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 data from swab testing in PHE labs and NHS data from swab testing for the -

Ageing Well Guide a Directory of Services, Clubs and Activities in Blaby District

Ageing Well Guide A directory of services, clubs and activities in Blaby District Published June 2016 Introduction Welcome to the new Ageing Well Guide for Blaby District. Our Ageing Population remains a priority for Blaby District Council. It is our vision that people are able to enjoy happy, healthy and independent lives, feeling involved and valued in their community during later life. Cllr David Freer – Portfolio Holder for Partnerships & Corporate Services – says: ‘Residents and professionals alike have told us what a valuable resource the Older Persons’ Guide has been and this new edition is bigger than ever. The Council and its partners provide a number of schemes that support our vision for our ageing population. The new Ageing Well Guide includes information about these and the numerous activities that are taking place across our parishes that are all helping in some way to reduce isolation and improve health and wellbeing’. The frst part of this guide provides information about district-wide services that provide help on issues such as health and social care, transport, community safety, money advice and library services. The second part of the guide gives details of clubs and activities taking place in each parish within the district, including GP practices, social or lunch clubs, ftness and exercise classes and special interest or hobby groups. 2 Blaby District Council has taken care to ensure the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. All information has been provided by third parties and the Council cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies in the information or any changes that may arise, such as changes to any fees, charges or activities listed. -

Glen Parva History

The Parish of Glen Parva Glen Parva is a civil parish in Leicestershire, United Kingdom with a population of over 5,000. It is bordered to the north by Aylestone and to the east by Eyres Monsell and South Wigston. Aylestone and Eyres Monsell are both districts of the City of Leicester. To the south and west it is bordered by open countryside. The Parish Council has its offices at the Memorial Hall on Dorothy Avenue. The Hall was built to commemorate residents of the Parish who fell in World War II. The Grand Union Canal near Glen Parva The Grand Union Canal passes to the south of the village where it runs parallel with the River Sence before the canal turns north, to the west of the village and then runs parallel to the River Soar. The Sence is a tributary of the Soar which in turn is a tributary of the River Trent. History “GLENN-PARVA, a township in Aylestone parish, Leicestershire; on the river Soar and the Union canal, 4 miles SSW of Leicester. Real property, £1,894. Pop., 119. Houses, 30.” (Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales 1870-72) Glen Parva was originally included in the Aylestone Ecclesiastical Parish but after the Local Government Act of 1894 it became a civil parish within the Rural District of Blaby. It is generally accepted that the original settlement of Glen Parva was situated near ‘The Ford’ on the River Sence, an area which is now known locally as ‘Glen Ford’. There is limited evidence of prehistoric activity in this area but excavations in 1962 on the site of a moated enclosure some 150m to the south-east of the area exposed a possible roundhouse, with a hearth, an oven and a cobbled surface associated with Late Bronze Age pottery. -

HMYOI Glen Parva

Report on a full unannounced inspection of HMYOI Glen Parva 2 – 6 November 2009 by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons Crown copyright 2010 Printed and published by: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons 1st Floor, Ashley House Monck Street London SW1P 2BQ England HMYOI Glen Parva 2 Contents Introduction 5 Fact page 7 Healthy prison summary 9 1 Arrival in custody Courts, escorts and transfers 19 First days in custody 20 2 Environment and relationships Residential units 23 Staff-prisoner relationships 26 Personal officers 28 3 Duty of care Bullying and violence reduction 31 Self-harm and suicide 35 Applications and complaints 37 Legal rights 38 Faith and religious activity 39 Substance use 41 4 Diversity 43 5 Health services 51 6 Activities Learning and skills and work activities 59 Physical education and health promotion 63 Time out of cell 64 7 Good order Security and rules 67 Discipline 68 Incentives and earned privileges 70 8 Services Catering 73 Prison shop 74 HMYOI Glen Parva 3 9 Resettlement Strategic management of resettlement 75 Offender management and planning 76 Resettlement pathways 79 10 Recommendations, housekeeping points and good practice 89 Appendices I Inspection team 102 II Prison population profile 103 III Safety and staff-prisoner relationship interviews 106 IV Summary of prisoner questionnaires and interviews 112 HMYOI Glen Parva 4 Introduction Glen Parva is a young offender institution in Leicester, holding around 800 sentenced, unsentenced and remanded young male prisoners aged 18 to 21. In recent inspections, we have charted the establishment’s progress towards providing a generally safe, respectful environment for its volatile population, increasingly focused on resettlement. -

Blaby District Council Ageing Well Guide

Ageing Well Guide A directory of services, clubs and activities in Blaby District Published June 2016 Introduction Welcome to the new Ageing Well Guide for Blaby District. Our Ageing Population remains a priority for Blaby District Council. It is our vision that people are able to enjoy happy, healthy and independent lives, feeling involved and valued in their community during later life. Cllr David Freer – Portfolio Holder for Partnerships & Corporate Services – says: ‘Residents and professionals alike have told us what a valuable resource the Older Persons’ Guide has been and this new edition is bigger than ever. The Council and its partners provide a number of schemes that support our vision for our ageing population. The new Ageing Well Guide includes information about these and the numerous activities that are taking place across our parishes that are all helping in some way to reduce isolation and improve health and wellbeing’. The first part of this guide provides information about district-wide services that provide help on issues such as health and social care, transport, community safety, money advice and library services. The second part of the guide gives details of clubs and activities taking place in each parish within the district, including GP practices, social or lunch clubs, fitness and exercise classes and special interest or hobby groups. 2 Blaby District Council has taken care to ensure the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. All information has been provided by third parties and the Council cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies in the information or any changes that may arise, such as changes to any fees, charges or activities listed. -

SAPCOTE NEWS Glenfield 56.68 Narborough 53.68 • Published by SRGMC Enderby 50.08 (Sapcote Recreational Ground Management Sapcote 47.50 Committee)

Issue: April 2007 S APCOTE NEWS YYourOUR Village VILLAGE Paper PAPER EDITORS: 2007/2008 Comparative Parish Council Precept Levels Christina Davey in Blaby District 59 Hinckley Road Tel: 273552 or It was reported in the last We can now report on what Sapcote, as reported in the issue that the Parish Council other parish councils within last issue, is levying a precept 07740 425447 had applied a less than Blaby District are charging below the £52.95 average for inflation increase to the per household based on Blaby parishes as the Emails: [email protected] Parish’s precept. Band D properties. following table shows. Council Charge per Household per year for Band D (£) Belinda Duggins Whetstone 88.74 6 Spring Gardens Braunstone 82.15 Tel: 271967 or Glen Parva 74.09 Blaby 73.94 07773 482399 Cosby 72.88 Countesthorpe 71.76 Huncote 63.42 SAPCOTE NEWS Glenfield 56.68 Narborough 53.68 • Published by SRGMC Enderby 50.08 (Sapcote Recreational Ground Management Sapcote 47.50 Committee). Stoney Stanton 42.78 Croft 39.66 • SRGMC has no opinions on the articles in this Thurlaston 39.32 edition. Leicester Forest East 34.82 Kirby Muxloe 34.07 • All articles submitted will be included in the earliest Kilby 30.62 edition where possible, Sharnford 29.78 and the editor on behalf Elmesthorpe 20.07 of the SRGMC reserves the right NOT to publish any material deemed to be unsuitable. WELCOME ALFIE DUGGINS!! • The views and opinions expressed in this and any On Friday 16th March our own edition are NOT those of editor Belinda Duggins gave birth the editors unless detailed to a baby boy. -

Everards Pubs

Pub Details Bus Route Aberdale Shackerdale Road, West Knighton, Leicester, LE2 6HT Arriva 44A Anchor Inn 74 Loughborough Road, Hathern, Leicestershire, LE12 5JB KinchBus Skylink Anne of Cleves 12 Burton Street, Melton Mowbray, LE13 1AE Arriva 5A Centrebus 100/128 Bakers Arms The Green, Blaby, Leicestershire, LE8 4FQ Arriva 84/85 Barley Mow 149 Granby Street, Leicester, LE1 6FE All City Centre Routes Birch Tree Bardon Road, Bardon Hill, LE67 1TD Arriva 29A/29X Black Dog 23 London Road, Oadby, LE2 5DL Arriva 31 Black Horse Braunstone Gate, Leicester, LE3 5LT Arriva 50/50A/51/52/104 First 18/19/20 Black Horse 65 Narrow Lane, Aylestone, Leicester, LE2 8NA Arriva 84/85/87 Centrebus 40/83 Blue Bell 39 High Street, Desford, Leicestershire, LE9 9JF Arriva 153 Blue Bell 20 Long Street, Stoney Stanton, Leicestershire, LE9 4DQ HinckleyBus X55 Bradgate Main Street, Newtown Linford, Leicestershire, LE6 0AE Roberts 120 Bricklayers Arms 213 Main Street, Thornton, Leicestershire, LE67 1AH Arriva 26 Bull Main Street, Broughton Astley, LE9 6RD Arriva 84 Bulls Head The Nook, Cosby, LE9 1RQ Arriva 84 Bulls Head Hinckley Road, Leicester Forest West, LE9 9JE Arriva 158 Stagecoach 48 Bulls Head 23 Main Street, Ratby, LE6 0LN Arriva 26/27 Bulls Head 44 Victoria Road, Whetstone, Leicestershire, LE8 6JX Arriva 84 Cheney Arms 2 Rearsby Lane, Gaddesby, LE7 4XE Centrebus 100 Cherry Tree Church Walk, Little Bowden, Market Harborough LE16 8AE Arriva X3 Stagecoach X7 Coach & Horses 54 Main Street, Lubenham, Leicestershire, LE16 9TF HinckleyBus 58 Coach & Horses 196 Leicester -

Vebraalto.Com

25 Glenhills Court Little Glen Road, Leicester, LE2 9DH For further details Guide price £159,995 LEASEHOLD please call 0345 556 4104 25 Glenhills Court Little Glen Road, Leicester, LE2 9DH A bright and spacious one bedroom retirement apartment. NO FORWARD CHAIN. Located in the ideal location just miles from Leicester city centre. Glenhills Court views as well as the perfect place for a morning stroll. .Glen Bedroom Glenhills Court is located beside the Grand Union Canal in Parva is a peaceful suburb to the south of the city, conveniently Double bedroom with a large mirror fronted wardrobe providing Glen Parva, just four miles from Leicester city centre. This fine situated to the M1 motorway. It is largely residential, with plenty of storage space. Double glazed window. TV, phone point collection of age-exclusive apartments is a must-see for those several small shops in its ‘Carvers Corner’, including a post and storage heater. Carpets, curtains and light fittings. seeking retirement living in Leicestershire; the complex office, chemist and newsagent. Nearby, you’ll find the large Bathroom includes one and two bedroom properties, which are spacious, Fosse Shopping Park, which features over thirty high street stylish, and offer the benefits of Retirement Living PLUS. stores. Glen Parva also benefits from a local park, library and Fully tiled and fitted bathroom with electric walk-in shower and An Estates Manager is on hand to manage the day to day memorial hall separate bath. Hand basin with vanity unit and mirrored cabinet running of the development and attend to any queries you may over. -

COVID 19 Cases in Leicestershire

Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 17/10/2020 This report summarises the information from the surveillance system which is used to monitor the cases of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Leicestershire. The report is based on daily data up to 17th October 2020. The maps presented in the report examine counts and rates of COVID-19 at Middle Super Output Area. Middle Layer Super Output Areas (MSOAs) are a census based geography used in the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales. The minimum population is 5,000 and the average is 7,200. Disclosure control rules have been applied to all figures not currently in the public domain. Counts between 1 to 7 have been suppressed at MSOA level. An additional dashboard examining weekly counts of COVID-19 cases by Middle Super Output Area in Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland can be accessed via the following link: https://public.tableau.com/profile/r.i.team.leicestershire.county.council#!/vizhome/COVID-19PHEWeeklyCases/WeeklyCOVID- 19byMSOA Data has been sourced from Public Health England. The report has been complied by Strategic Business Intelligence in Leicestershire County Council. Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 17/10/2020 Breakdown of testing by Pillars of the UK Government’s COVID-19 testing programme: Pillar 1 + 2 Pillar 1 Pillar 2 combined data from both Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 data from swab testing in PHE labs and NHS data from swab testing for the -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 08/01/2015, 16.30

To Members of the Development Control Committee Dear Councillor, Please find attached the following information items which relate to the DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE taking place on THURSDAY, 8 JANUARY 2015 at 4.30 p.m. INFORMATION ITEMS 6. Information Reports (Pages 3 - 18) Blaby District Council Council Offices Desford Road Narborough Leicestershire LE19 2EP Telephone: 0116 275 0555 Fax: 0116 275 0368 Minicom: 0116 284 9786 Web: www.blaby.gov.uk This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 6 INFORMATION REPORTS Committee Name of Report Officer Development Control Appeal Decision Ms. K. Ingles ± Committee ± 08/01/15 Development Services Delegated Reports Manager Tel: 0116 272 2301 Page 3 BLABY DISTRICT COUNCIL 8 JANUARY 2015 REPORT OF THE PLANNING & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT GROUP MANAGER INFORMATION ITEM APPEAL DECISION Crematorium Management Ltd Change of use of land to form new Crematorium with ancillary book of remembrance building, floral tribute area, memorial areas, garden of remembrance and associated parking and infrastructure ± Land off Welford Road, Kilby Application Number: 14/0356/1/PX ___________________________________ Since your last meeting, confirmation has been received that the Inspector has DISMISSED the above appeal. A copy of the decision, together with a plan showing the site, is attached hereto for the information of Members. Background Papers File 14/0356/1/PX is held in the Planning Division. Cat Hartley 11 December 2014 Planning & Economic Development Group Manager Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12 DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE For Information Only APPROVALS ISSUED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS Plan No.