GIPE-071956.Pdf (4.127Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order Sheet in the Islamabad High Court, Islamabad

Form No: HCJD/C-121 ORDER SHEET IN THE ISLAMABAD HIGH COURT, ISLAMABAD (JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT) W. P. No.676/2017 Shahzada Sikandar ul Mulk & 4 others Versus The Capital Development Authority & 4 others Petitioners by : Dr. Muhammad Aslam Khakhi, Advocate. Syed Asghar Hussain Sabwari, Advocate. Dr Babar Awan, Advocate. Mr Sajjar Abbas Hamdani, Advocate. Mr Qausain Faisal Mufti, Advocate. Mr Tajammal Hussain Lathi, Advocate. Malik Zafar Husain, Advocate. Mr Ishtiaq Ahmed Raja, Advocate. Ms Kalsoom Rafique, Advocate. Ms Yasmin Haider, Advocate. Respondents by : Mr Fiaz Ahmed Anjum Jandran, Advocate. Mr Babar Sattar, Advocate. Mr Sultan Mazhar Sher, Advocate. Mr Waqar Hassan Janjua, Advocate. Malik Qamar Afzal, Advocate. Mr Khurram Mehmood Qureshi, Advocate. Mr Muhammad Anwar Mughal, Advocate. Ch. Hafeez Ullah Yaqoob, Advocate. Mr Muhammad Waqas Malik, Advocate. Mr Amjad Zaman, Advocate. Mr Muhammad Khalid Zaman, Advocate. Mr Mujeeb ur Rehman Kiani, Advocate. Barrister Jehangir Khan Jadoon, Advocate. Malik Mazhar Javed, Advocate. Raja Inam Amin Minhas, Advocate. Ch. Waqas Zamir, Advocate. Fazal ur Rehman, Advocate. Ms Zaitoon Hafeez, Advocate. -2- W.P No.676/2017 Ms Zainab Janjua, Advocate. Barrister Amna Abbas, Advocate. Ms Ayesha Ahmed, Advocate. Mr Kashif Ali Malik, Advocate. Mr Amir Latif Gill, Advocate. Mr Tariq Mehmood Jehangiri, Advocate General, Islamabad Capital Territory. Mr Awais Haider Malik, State Counsel. Mr Asad Mehboob Kiyani, Member (P&D), Mr Zafar Iqbal, Director (Master Plan), Mr Faraz Malik, Director (HS), Sh. Ijaz, Director (Urban Planning), Mr Arshad Chohan, Director (Rural Planning), for Capital Development Authority. Mr Mehrban Ali, & Arbab Ali, Zoologists on behalf of Secretary, M/o Climate Change. Date of Hearing : 19-04-2018. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online Pakistan Post PKA PK

Parcel Post Compendium Online PK - Pakistan Pakistan Post PKA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 50 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 50 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of information -

List of Ngos

Registration Sr. Name of NGO Address Status(Reg No,& No Date & Relevant Law Malot Commercial Center, Shahpur VSWA/ICT/494 ,Date: 1. Aas Welfare Association Simly Dam Road, Islamabad. 051- 6/9/2006, VSWA 2232394, 03005167142 Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/439, Village Khana Dak, Madina Town, Date:31/3/2004, 2. Abaseen Welfare Society Jabbah, Barma Chowk, Islamabad. VSWA Ordinance 03005308511 1961 Office No.5, 1st Floor, A & K Plaza, F- VSWA/ICT/511,Date 3. Acid Survivors Foundation. 10 Markaz, Islamabad. 051-2214052, 02/08/2007, VSWA 03008438984 Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/282, Date Ali Pur Frash Lehtrar Road, 4. Akhmat Welfare Centre 24/04/1998, VSWA Islamabad. 051-2519062 Ordinance 1961 Al Mustafa Towers VSWA/ICT/438, Date # 204, Al Mustafa Towers F-10 5. Residents Associations 27/03/2004,VSWA Markaz, Islamabad. 03458555872 (AMPTRWA) Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/520, Date Al-Firdous Welfare Mohallah Ara, Bharakau, Islamabad. 6. 2/04/2008, VSWA Association 051-2512308, 03008565227 Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/261,Date:0 Model Village Ali Pur Farash 7. Al-Itehad Welfare Society 5/08/1996, VSWA Islamabad. Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/202,Date:1 NearF.G.Boys High School Shahdra 8. Al-Jihad Youth Organization 7/06/1993,VSWA Islamabad Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/377, Date H.No.39 Gali No.67 I- 9. Al-Noor Foundation. 17.4.2002, VSWA 10/1,Islamabad.051-4443227 Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/90, Date 10. Al-Noor Islamic Center Rawal Town Islamabad 2.12.1990 VSWA Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/89, Date 11. Al-Noor Islamic Center Sharifabad Tarlai Islamabad 2.12.1990 VSWA Ordinance 1961 VSWA/ICT/271, Date PEC Building, Ataturk Avenue, G-5/2, 12. -

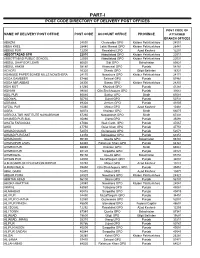

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

The Study on Improvement of Management Information Systems in Health Sector in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan Dhis Manual

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF HEALTH, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN THE STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN HEALTH SECTOR IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN DHIS MANUAL FEBRUARY 2007 NATIONAL HEALTH INFORMATION RESOURCE CENTER HM SYSTEM SCIENCE CONSULTANTS INC. JR 06-46 Japan International Cooperation Agency Ministry of Health, Islamic Republic of Pakistan THE STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN HEALTH SECTOR IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN FINAL REPORT DHIS MANUAL February 2007 System Science Consultants Inc PART I PROCEDURES MANUAL Procedures Manual For District Health Information System (DHIS) Pakistan The Study on Improvement of Management Information Systems in Health Sector in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan National Health Information Resource Center, Ministry of Health, Pakistan Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Systems Science Consultants, Inc. Contents Table 1 List of DHIS Instruments......................................................................................1 Table 2 When and Who Fills the DHIS Instruments.........................................................2 Table 3 Source of Data for DHIS Monthly Reports ........................................................82 Table 4 Detail Description of Data Source for DHIS Monthly Report ...........................83 Procedures Manual 1. Central Registration Point Register .................................................................................4 2. OPD Ticket ....................................................................................................................8 -

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 8

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 8 Criteria CHAKWAL Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 92.71% 87.61% PASS Pass + Pass Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 94.06% 89.28% with Grace marks in one subject Marks Pass + Pass with Grace Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four 99.08% 96.89% Marks + subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Pass + Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Gender Promoted Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Promoted % Students Male 7754 7698 7058 91.69 7615 98.92 Public School Female 8032 7982 7533 94.37 7941 99.49 Male 1836 1810 1652 91.27 1794 99.12 Private School Female 1568 1559 1484 95.19 1555 99.74 Male 496 471 390 82.80 444 94.27 Private Candidate Female 250 243 205 84.36 232 95.47 19936 19763 18322 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Overall Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-232-295 Muhammad Abdul Rehman 479 1st 65-141-174 Maryam Batool 476 2nd 65-141-208 Wajeeha Gul 476 2nd 65-208-182 Sawaira Azher 474 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Male Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-232-295 Muhammad Abdul Rehman 479 1st 65-231-135 Muhammad Huzaifa 468 2nd 65-183-183 Fasih Ur Rehman 463 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL FEMALE Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-141-174 Maryam Batool 476 1st 65-141-208 Wajeeha Gul 476 1st 65-208-182 Sawaira Azher 474 2nd 65-236-232 Kiran Shaheen 473 3rd j b i i i i Punjab Examination Commission Grade 8 Examination 2019 School wise Results Summary Sr. -

Population Census of Pakistan 1961

( ·~ " POPULATION CENSUS OF PAKISTAN 1961 ~ DISTRICT CENSUS REPORT -RAWALPINDI PART-V rV lllAGE STATISJ.ics· 'COMPIL~D BY i<i-iA ·~ BASHIR AHMED KAAN 'ASSJSTANT DIRECTOR OF cENSUS Ri\WALPINoi ~ lt ~':"",.a;ll!;. mn=-rr:n INTRODUCTION The village is the ba sic unit of revenue The Village Statistics contained in this administration and the need for basic statis part have been compiled from Block-wise tics for villages is quite obvious as au plan fi gures contained in the Summaries prepared ning depends on such statistics. They are a lso by the Census Supervisors and Charge indispensable fo r carrying out sample surveys Superintendents. Except for data on houses over limited areas and form the basis of contin and houseJ10lds they are based on the results uous collection ofs tatistics on different aspects of the "Circle Sort"' which was carried out in of rural life and economy. The village was ta ken the Hand Sorting Centres after the physical as the basic unit of enumeration if its popula counting of the individual enumeration tion was 600 or it was a continuous collection schedules. The literacy figures, however, have of about 150 houses on an average. Where been lifted from the Summaries prepared by the village approximated to this size, it was the Supervisors and Charge Superintendents. constituted into a Block. A large nu mber of villages ha d to be split up into a number of The plan of presentati on is that for each Blocks, but the boundaries of Census Block village, the Hadbast number, its name in did not go beyond the limits of a revenue English and Urdu a nd a rea in acres, the estate. -

Vulnerability of Agriculture to Climate Change in Chakwal District: Assessment of Farmers’ Adaptation Strategies

VULNERABILITY OF AGRICULTURE TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAKWAL DISTRICT: ASSESSMENT OF FARMERS’ ADAPTATION STRATEGIES SARAH AMIR Reg. No. 4-FBAS/PHDES/F13 Department of Environmental Science Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD 2020 VULNERABILITY OF AGRICULTURE TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN CHAKWAL DISTRICT: ASSESSMENT OF FARMERS’ ADAPTATION STRATEGIES A thesis submitted to the Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences in fulfillment of the requirement for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy of International Islamic University, Islamabad. SARAH AMIR Registration No: 4/FBAS/PHDES/F13 Supervisor Dr. Muhammad Irfan Khan Professor Department of Environmental Science Co-supervisors Dr. Zafeer Saqib Dr. Muhammad Azeem Khan Assistant Professor Chairman Department of Environmental Science Pakistan Agricultural Research Council Spring 2020 Department of Environmental Science Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD DEDICATION I dedicate my work to my beloved parents, husband, children, family members, friends and respectable teachers for their unconditional support and love. ACCEPTANCE BY THE VIVA VOCE COMMITTEE Title of Thesis: Vulnerability of Agriculture to Climate Change in Chakwal District: Assessment of Farmers’ Adaptation Strategies Name of Student: Sarah Amir Registration No: 4/FBAS/PHDES/F13 Accepted by the Doctoral Research Committee of the Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences, for the award -

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and Their Branches (December 31, 2008)

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and their Branches (December 31, 2008) Allied Bank Ltd. Bhalwal (2) Chishtian (2) -Grain Market -Grain Market (743) -Noor Hayat Colony -Mohar Sharif Road Abbaspur 251 RB Bandla Bheli Bhattar (A.K.) Chitral Chungpur (A.K.) Abbottabad (4) Burewala (2) Dadu -Bara Towers, Jinnahabad -Grain Market -Pineview Road -Housing Scheme Dadyal (A.K) (2) -Supply Bazar -College Road -The Mall Chak Jhumra -Samahni Ratta Cross Chak Naurang Adda Johal Chak No. 111 P Daharki Adda Nandipur Rasoolpur Chak No. 122/JB Nurpur Danna (A.K.) Bhal Chak No. 142/P Bangla Danyor Adda Pansra Manthar Darband Adda Sarai Mochiwal Chak No. 220 RB Dargai Adda Thikriwala Chak No. 272 HR Fortabbas Darhal Gaggan Ahmed Pur East Chak No. 280/JB (Dawakhri) Daroo Jabagai Kombar Akalgarh (A.K) Chak No. 34/TDA Daska Arifwala Chak No. 354 Daurandi (A.K.) Attock (Campbellpur) Chak No. 44/N.B. Deenpur Bagh (A.K) Chak No. 509 GB Deh Uddhi Bahawalnagar Chak No. 76 RB Dinga Chak No. 80 SB Bahawalpur (5) Chak No. 88/10 R Dera Ghazi Khan (2) Chak No. 89/6-R -Com. Area Sattelite Town -Azmat Road -Dubai Chowk -Model Town -Farid Gate Chakwal (2) -Ghalla Mandi -Mohra Chinna Dera Ismail Khan (3) -Settelite Town -Talagang Road -Circular Road -Commissionery Bazar Bakhar Jamali Mori Talu Chaman -Faqirani Gate (Muryali) Balagarhi Chaprar Balakot Charsadda Dhamke (Faisalabad) Baldher Chaskswari (A.K) Dhamke (Sheikhupura) Bucheke Chattar (A.K) Dhangar Bala (A.K) Chhatro (A.K.) Dheed Wal Bannu (2) Dina -Chai Bazar (Ghalla Mandi) Chichawatni (2) Dipalpur -Preedy Gate -College Road Dir Barja Jandala (A.K) -Railway Road Dunyapur Batkhela Ellahabad Behari Agla Mohra (A.K.) Chilas Eminabad More Bewal Bhagowal Faisalabad (20) Bhakkar Chiniot (2) -Akbarabad Bhaleki (Phularwan Chowk) -Muslim Bazar (Main) -Sargodha Road -Chibban Road 415 ABL -Factory Area -Zia Plaza Gt Road Islamabad (23) -Ghulam Muhammad Abad Colony Gujrat (3) -I-9 Industrial Area -Gole Cloth Market -Grand Trunk Road -Aabpara -Gole Kiryana Bazar -Rehman Saheed Road -Blue Area ABL -Gulburg Colony -Shah Daula Road. -

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornament & Valuables

PUBLIC NOTICE AUCTION OF GOLD ORNAMENT & VALUABLES Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized from such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank as mentioned hereunder: Customer Sr. No. Customer's Name Address Balance as on 12th October 2020 Number 1 1038553 ZAHID HUSSAIN MUHALLA MASANDPURSHI KARPUR SHIKARPUR 327,924 2 1012051 ZEESHAN ALI HYDERI MUHALLA SHIKA RPUR SHIKARPUR PK SHIKARPUR 337,187 3 1008854 NANIK RAM VILLAGE JARWAR PSOT OFFICE JARWAR GHOTKI 65110 PAK SITAN GHOTKI 565,953 4 999474 DARYA KHAN THENDA PO HABIB KOT TALUKA LAKHI DISTRICT SHIKARPU R 781000 SHIKARPUR PAKISTAN SHIKARPUR 298,074 5 352105 ABDUL JABBAR FAZALEELAHI ESTATE S HOP -

Rawalpindi 1 Rawalpindi Leprosy Hospital, Zafar-Ul-Haq Road P.O Box No

Valid X-ray License Holder Sr. Facility Rawalpindi 1 Rawalpindi Leprosy Hospital, Zafar-ul-Haq Road P.O Box No. 135, Rawalpindi 2 Al-Shifa Eye Hospital, Jehlum Road, Rawalpindi 3 Health Ways Medical Centre, 8-111, Murree Road Opp. Ministry of Defence Secretrait, Saddar, Rawalpindi 4 Habib Hospital, Saidpur Road, Banni, Rawalpindi 5 Armed Forces Institute of Cadialogy(AFIC), The Mall Road, Rawalpindi 6 Christian Hospital, Faisal Shahid Road, Taxila, Rawalpindi 7 Islamic International Medical Complex Trust, Railway Hospital, Westridge, Rawalpindi 8 Abrar Surgery (Pvt.) Ltd, 219-B(1), Peshawar Road, Rawalpindi 9 Abrar Diagnostic Centre, 312-E, Chairing Cross Peshawar Road, Rawalpindi 10 WAPDA Hospital, Marrier Hassan, Rawalpindi 11 Combined Military Hospital, Murree, Rawalpindi 12 Attock Hospital(Pvt.) Ltd., P. O. Refinary Morgah, Rawalpindi 13 Kahuta Research Laboratories (KRL) Hospital, P. O. Sumbulgah, Tehsil Kahuta, Rawalpindi 14 KRL Medical Center, Dr. A. Q. Khan Road, P. O. Box 502, Rawalpindi 15 Urgent Medical Centre, Medical Tower, 101-A 6th Road, Satellite Town, Rawalpindi 16 Adil Diagnostics, B-1315, Saidpur Road, Rawalpindi 17 Valley Clinic (Pvt.) Ltd., 213, Peshawar Road, Lane 4, Rawalpindi 18 Maryam Memorial Hospital, Peshawar Road, Rawalpindi 19 Dr. Aslam Uppal Hospital & Labs, 3-Quaid Avenue Near Aslam Uppal Square, Lalazar, Wah Cantt., Rawalpindi 20 C/o Dr. Amenah Dental Clinic, 167/3A, Adamjee Road, Rawalpindi, Rawalpindi 21 Margalla Hospital, Pirwadahi Road, Pirwadahi, Rawalpindi 22 Al-Noor Dental Clinic, Mushtaq Plaza Holy Family Chowk Saidpur Raod, Rawalpindi 23 Hearts International Hospital, 192-A, The Mall, Rawalpindi 24 Al-Mustafa Trust Medical Center, Street No. 14, Mini Market Chaklala Scheme-III, Rawalpindi 25 Aman Hospital, 519/8-A, Misrial Road, Rawalpindi 26 DHQ Hospital, Raja Bazar, Rawalpindi 27 HIT Hospital, Taxila Cantt., Taxila, Rawalpindi 28 Syed Mohd Hussain Govt. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of City District Government Rawalpindi Audit

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF CITY DISTRICT GOVERNMENT RAWALPINDI AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS............................................................................................. I PREFACE...................................................................................................................................... III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... IV SUMMARY TABLE & CHARTS ............................................................................................ VIII TABLE 1: AUDIT WORK STATISTICS ................................................................................... VIII TABLE 2: AUDIT OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................................ VIII TABLE3: OUTCOME STATISTICS ............................................................................................ IX TABLE4: IRREGULARITIES POINTED OUT ............................................................................. X TABLE 5 COST BENEFIT ............................................................................................................. X CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CITY DISTRICT GOVERNMENT RAWALPINDI ........................................................ 1 1.1.1 INTRODUCTION OF DEPARTMENTS ........................................................................