Continuum of Fujian Language Boundary Perception: Dialect Division and Dialect Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Service Summary

COSCO SHIPPING TRANSPACIFIC SERVICE OVERVIEW Service Summary 23 SERVICE LINES cover 161 PORT PAIRS since 1st. April, 2017 * Including COSCO SHIPPING Out-Alliance Service Lines PSW/PNW/AWE SERVICE LINE OVERVIEW PSW Service Summary 12 Far-east to Southwest Coast of America Service lines Cover 61 Port Pairs CEN (COSCO)* AAC (COSCO) AAC2 (CMA+EMC) AAC3 (COSCO+WHL+PIL)** AAC4 (OOCL) Service 6 X 10000 6 X 10000 6 X 9000 6 X 8500 5 X 7800 Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB XINGANG 0 DALIAN 0 QINGDAO 0 QINGDAO 0 NINGBO 0 QINGDAO 3 LIANYUNGANG 1 SHANGHAI 2 SHANGHAI 2 SHANGHAI 1 SHANGHAI 5 SHANGHAI 4 NINGBO 4 NINGBO 3 PUSAN 4 Port Load of Port NINGBO 6 PRINCE RUPERT 17 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 18 LONG BEACH 17 LONG BEACH 16 LONG BEACH 22 SEATTLE 28 OAKLAND 23 OAKLAND 22 PUSAN 33 OAKLAND 27 DALIAN 42 TOKYO 38 QINGDAO 42 NINGBO 35 XINGANG 42 NAGOYA 39 QINGDAO 42 Port Discharge of Port *The details of all the services will be optimized further. ** COSCO SHIPPING’s Out-Alliance Service Lines PSW Service Summary 12 Far-east to Southwest Coast of America Service lines Cover 61 Port Pairs AAS (OOCL) AAS2 (CMA) AAS3 (EMC) AAS4 (EMC) Service 6 X 9000 6 X 14000 6 X 6500 6 X 7000 Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB Port ETB CAI MEP 0 FUQING 0 TAIPEI 0 YANTIAN 0 SHEKOU 3 NANSHA 2 XIAMEN 3 HONG KONG 1 HONG KONG 3 HONG KONG 3 SHEKOU 4 KAOHSIUNG 3 Port of Load Port YANTIAN 4 YANTIAN 4 YANTIAN 5 TAIPEI 4 KAOHSIUNG 6 XIAMEN 6 LONG BEACH 19 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 20 LONG BEACH 18 KAOHSIUNG 38 OAKLAND 25 OAKLAND 24 OAKLAND 22 CAI MEP 42 FUQING 42 TAIPEI 42 -

Filariasis and Its Control in Fujian, China

REVIEW FILARIASIS AND ITS CONTROL IN FUJIAN, CHINA Liu ling-yuan, Liu Xin-ji, Chen Zi, Tu Zhao-ping, Zheng Guo-bin, Chen Vue-nan, Zhang Ying-zhen, Weng Shao-peng, Huang Xiao-hong and Yang Fa-zhu Fujian Provincial Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Fuzhou, Fujian, China. Abstract. Epidemiological survey of filariasis in Fujian Province, China showed that malayan filariasis, transmitted by Anopheles lesteri anthropophagus was mainly distributed in the northwest part and bancrof tian filariasis with Culex quinquefasciatus as vector, in middle and south coastal regions. Both species of filariae showed typical nocturnal periodicity. Involvement of the extremities was not uncommon in mala yan filariasis. In contrast, hydrocele was often present in bancroftian filariasis, in which limb impairment did not appear so frequently as in the former. Hetrazan treatment was administered to the microfilaremia cases identified during blood examination surveys, which were integrated with indoor residual spraying of insecticides in endemic areas of malayan filariasis when the vector mosquito was discovered and with mass treatment with hetrazan medicated salt in endemic areas of bancroft ian filariasis. At the same time the habitation condition was improved. These factors facilitated the decrease in incidence. As a result malayan and bancroftian filariasis were proclaimed to have reached the criterion of basic elimination in 1985 and 1987 respectively. Surveillance was pursued thereafter and no signs of resurgence appeared. DISCOVER Y OF FILARIASIS time: he found I male and 16 female adult filariae in retroperitoneallymphocysts and a lot of micro Fujian Province is situated between II S050' filariae in pulmonary capillaries and glomeruli at to 120°43' E and 23°33' to 28°19' N, on the south 8.30 am (Sasa, 1976). -

Returning to China I Am Unsure About CLICK HERE Leaving the UK

Praxis NOMS Electrronic Toolkit A resource for the rresettlement ofof Foreign National PrisonersPrisoners (FNP(FNPss)) www.tracks.uk.net Passport I want to leave CLICK HERE the UK Copyright © Free Vector Maps.com I do not want to CLICK HERE leave the UK Returning to China I am unsure about CLICK HERE leaving the UK I will be released CLICK HERE into the UK Returning to China This document provides information and details of organisations which may be useful if you are facing removal or deportation to China. While every care is taken to ensure that the information is correct this does not constitute a guarantee that the organisations will provide the services listed. Your Embassy in the UK Embassy of the People’s Republic of China Consular Section 31 Portland Place W1B 1QD Tel: 020 7631 1430 Email: [email protected] www.chinese-embassy.org.uk Consular Section, Chinese Consulate-General Manchester 49 Denison Road, Rusholme, Manchester M14 5RX Tel: 0161- 2248672 Fax: 0161-2572672 Consular Section, Chinese Consulate-General Edinburgh 55 Corstorphine Road, Edinburgh EH12 5QJ Tel: 0131-3373220 (3:30pm-4:30pm) Fax: 0131-3371790 Travel documents A valid Chinese passport can be used for travel between the UK and China. If your passport has expired then you can apply at the Chinese Embassy for a new passport. If a passport is not available an application will be submitted for an emergency travel certificate consisting of the following: • one passport photograph • registration form for the verification of identity (completed in English and with scanned -

Adapting MARBERT for Improved Arabic Dialect Identification

Adapting MARBERT for Improved Arabic Dialect Identification: Submission to the NADI 2021 Shared Task Badr AlKhamissi∗ Mohamed Gabr∗ Independent Microsoft EGDC badr [at] khamissi.com mohamed.gabr [at] microsoft.com Muhammed ElNokrashy Khaled Essam Microsoft EGDC Mendel.ai muelnokr [at] microsoft.com khaled.essam [at] mendel.ai Abstract syntax, morphology, vocabulary, and even orthog- raphy. Dialects may be heavily influenced by pre- In this paper, we tackle the Nuanced Ara- viously dominant local languages. For example, bic Dialect Identification (NADI) shared task Egyptian variants are influenced by the Coptic lan- (Abdul-Mageed et al., 2021) and demonstrate guage, while Sudanese variants are influenced by state-of-the-art results on all of its four sub- the Nubian language. tasks. Tasks are to identify the geographic ori- gin of short Dialectal (DA) and Modern Stan- In this paper, we study the classification of such dard Arabic (MSA) utterances at the levels of variants and describe our model that achieves state- both country and province. Our final model is of-the-art results on all of the four Nuanced Ara- an ensemble of variants built on top of MAR- bic Dialect Identification (NADI) subtasks (Abdul- BERT that achieves an F1-score of 34:03% for Mageed et al., 2021). The task focuses on distin- DA at the country-level development set—an guishing both MSA and DA by their geographi- improvement of 7:63% from previous work. cal origin at both the country and province levels. The data is a collection of tweets covering 100 1 Introduction provinces from 21 Arab countries. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

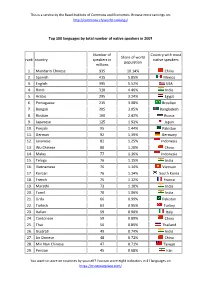

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

(AHP)-Based Assessment of the Value of Non-World Heritage Tulou

Tourism Management Perspectives 26 (2018) 67–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tourism Management Perspectives journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tmp Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)-based assessment of the value of non- T World Heritage Tulou: A case study of Pinghe County, Fujian Province ⁎ Hang Maa, Shanting Lib, Chung-Shing Chanc, a Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen Graduate School, Shenzhen 518050, China b Shanghai W&R Group, Shanghai 200052, China c Department of Geography and Resource Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, N.T, Hong Kong ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: China's Fujian Tulou (earthen buildings constructed dating to the 12th century) represent a valuable source of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) human cultural heritage. As the Tulou have not been classified as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, they lack Conservation and reuse financial support, receive minimal attention and face structural deterioration. The purpose of this study is to Cultural heritage explore a methodological approach to assess the value of non-World Heritage Tulou (NWHT) and provide Evaluation system grounds for the reuse of Tulou accordingly. First, building-type, planar layout and other characteristics of Pinghe Tulou NWHTs in Pinghe are reviewed. Next, an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is applied to the value evaluation of Pinghe Tulou. Then, policy recommendations for reuse and redevelopment are put forward. The findings suggest that focusing on the reuse of Tulou alone is not justifiable. Rather, funding, public participation and the con- tinuity of community life are important factors relating to the reuse of NWHTs. 1. Introduction Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2008 (and are thus referred to here as ‘World Heritage Tulous’ (Fig. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait Through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks

sustainability Article Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks Yan Ma * and Feng Xue School of Architecture and Urban-Rural Planning, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, Fujian, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 April 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2019; Published: 24 May 2019 Abstract: Globalization and the spread of information have made city networks more complex. The existing research on city network structures has usually focused on discussions of regional integration. With the development of interconnections among cities, however, the characterization of city network structures on a regional scale is limited in the ability to capture a network’s complexity. To improve this characterization, this study focused on network structures at both regional and local scales. Through the lens of function and innovation, we characterized the city network structure of the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through a social network analysis and a Fast Unfolding Community Detection algorithm. We found a significant imbalance in the innovation cooperation among cities in the region. When considering people flow, a multilevel spatial network structure had taken shape. Among cities with strong centrality, Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Whenzhou had a significant spillover effect, which meant the region was depolarizing. Quanzhou and Ganzhou had a significant siphon effect, which was unsustainable. Generally, urbanization in small and midsize cities was common. These findings provide support for government policy making. Keywords: city network; spatial organization; people flows; innovation network 1. -

Fujian's Industrial Eco-Efficiency

sustainability Article Fujian’s Industrial Eco-Efficiency: Evaluation Based on SBM and the Empirical Analysis of lnfluencing Factors Xiaoqing Wang *, Qiuming Wu, Salman Majeed * and Donghao Sun School of Economics and Management, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350000, China; [email protected] (Q.W.); [email protected] (D.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (S.M.); Tel.: +86-(0)-379-608-92800 (S.M.) Received: 17 July 2018; Accepted: 13 September 2018; Published: 18 September 2018 Abstract: The coordinated development of industrialization and its ecological environment are vital antecedents to sustainable development in China. However, along with the accelerating development of industrialization in China, the contradiction between industrial development and environment preservation has turned out to be increasingly evident and inevitable. Eco-efficiency can be seen either as an indicator of environmental performance, or as a business strategy for sustainable development. Hence, industrial eco-efficiency promotion is the key factor for green industrial development. This study selects indicators relevant to resources, economy, and the environment of industrial development, and the indicators can well reflect the characteristics of industrial eco-efficiency. The SBM (Slacks-Based Measure) model overcomes the limitations of a radial model and directly accounts for input and output slacks in the efficiency measurements, with the advantage of capturing the entire aspect of inefficiency. This study evaluates the industrial eco-efficiency of nine cities in Fujian province during the period of 2006–2016, based on undesired output SBM (Slacks-Based Measure) model and also uses a Tobit regression model to analyze the influencing factors. The results show that there is a positive correlation among the economic development level, opening level, research and development (R&D) innovation, and industrial eco-efficiency in Fujian Province.