The Best from Two Schools …

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinity 2020 Calendar-2.Pdf

Week 11B August Mon 22 End of Year Examination Marks & Grades for Sat 1 Shell & Lower Vth Entered 5:15pm Sun 2 WSC Global at the Prague Ends Tue 23 Prefects Induction 8:30am-3:00pm Wed 24 Tutor Reports for Shell, Lower Vth & Lower VI Entered Mon 3 Common Room Meeting (Shell) 4:15pm Tue 4 End of Year Concert 7:00pm Wed 5 Thu 25 UK Cricket Tour Departs Thu 6 Fri 26 Term Ends 10:00am Fri 7 Sat 27 Sat 8 Sun 28 Sun 9 Mon 29 Mt Kilimanjaro Gold PA Expedition Departs Mon 10 Shell & Lower Vth End of Year Examination Results & Tue 11 Provisional CIE IGCSE & A Level Results Available Lower VI Tutor Reports Emailed to Parents Wed 12 Tue 30 Business/Economics Trip to Singapore, Malaysia and Thu 13 Provisional Edexcel A Level Results Available Dubai Returns Fri 14 Sat 15 July Sun 16 Wed 1 Thu 2 Mon 17 FORTHCOMING DATES Fri 3 P1 Speech Day Tue 18 Sat 4 Wed 19 MICHAELMAS 2020 Sun 5 Thu 20 Provisional Edexcel IGCSE Results Available Boarders Return: Monday, 31st August Mon 6 UK Cricket Tour Returns Fri 21 Term Begins: Tuesday, 1st September Mt Kilimanjaro Gold PA Expedition Returns Sat 22 Half Term: Begins, Friday, 16th October Tue 7 Sun 23 Boarders Return: Sunday, 25th October th Peponi School Wed 8 Term Restarts: Monday, 26 October Thu 9 Mon 24 Induction of New Members of the Common Room 9:00am Term Ends: Friday, 11th December Fri 10 Tue 25 Induction of New Members of the Common Room 9:00am Sat 11 Wed 26 HILARY 2021 Sun 12 Thu 27 Boarders Return: Sunday, 10th January Fri 28 Term Begins: Monday, 11th January Mon 13 Sat 29 Shell Induction Half Term: Begins, -

27Th September, 2019 Issue 18

Day BASKETBALL CAMP THIS ISSUE 6th September, 2014 Issue No. 13- 1 2014– 2015 Term 1 Week 1 2 IN THIS BULLETIN THIS ISSUE Page 2 – Message from Headteacher; Art Competition 27th September, 2019 Page 3 – Message Executive Headteacher; Music Notices; Page 4 – Junior School Issue 18 – 2 Page 5 – Sixth Form ; Hillcrest Hikers Page 6 – Inspiration from Learning Support Term 1 Page 7 – Boys’ Sports; Calendar Page 8 – Football Poster Page 9 – Girls’ Sports Week 4 Mr. John Eveson Headteacher 0786 888 890 [email protected] Mrs. Razwana Kimutai Deputy Headteacher 0710 540 079 [email protected] Ms. Tiffaney Algar Deputy Headteacher 0717 041 506 [email protected] Mr. Maurice Otieno Head of Senior School 0722 740 795 [email protected] Ms. Jane Akelola Head of Middle School 0733 714 579 [email protected] Mrs. Kira Channa Head of Junior School 0723 688 666 [email protected] MESSAGE FROM THE HEADTEACHER Joining two schools into one is no small challenge. On Friday 13th September our Year 9 students departed for a successful bonding trip together with their Head of Year, Mrs Kira Channa and their form teachers. Last Friday 20th September the Year 10 students also departed for their bonding weekend. They all apparently “had a blast”, enjoyed each other’s company and established friendships which will last long after they leave Hillcrest. My thanks go to all the staff who gave up their weekends to make lasting memories and begin the process of building one school so well. -

CJW Breakfast Presentation Vfinal

Presentation to CJW Clients Introduction to Cytonn & Real Estate Investment Opportunities June 2016 Table of Contents I. Overview of the Firm II. Investment Asset Classes III. Joint Ventures IV. Real Estate Deal Showcases 2 I: Overview of the Firm This image 3 160 Members, 1 Agenda – The Client This image 4 Introduction to Cytonn Investments Cytonn Investments is an independent investments management company • Our mission is that “we wo rk to deliver innovative & differentiated financial solutions that speak to our clients needs” • Cytonn Investments is differentiated in several respects: 1. Independence & Investor Focus: Cytonn is solely focused on serving the interest of clients, which is best done on an independent investment management platform to minimize conflicts of interest 2. Alternative Investments: Specialized focus on alternative assets - real estate, private equity, and structured products 3. Partnerships with GloBal Institutional Investors: Such as Taaleri of Finland 4. Strong Alignment: Every staff member participates in ownership. When clients do well, the firm does well; and when the firm does well, staff do well This image 5 Cytonn’s Corporate Structure – Kshs 73 bn Under Mandate Cytonn Investments Kenya United States Cytonn Cytonn Cytonn Real Private Cytonn Investments Investments Estate Equity Diaspora Ltd LLC • Independent • Development affiliate • Financial Services • Diaspora platform • US advisory and investment providing investment • Education connecting investors investment management grade real estate • Technology in the diaspora with management company, serving development opportunities in the company HNW & institutional solutions East African Region clients This image 6 Board of Directors The board is comprised of 10 members from diverse backgrounds, each bringing in unique skill-sets Prof. -

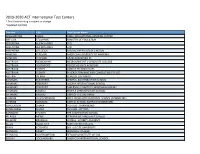

2019-2020 ACT International Test Centers * Test Center Listing Is Subject to Change

2019-2020 ACT International Test Centers * Test Center listing is subject to change. *Updated 2/24/20 Country City Test Center Name AFGHANISTAN KABUL KABUL EDUCATIONAL ADVISING CENTER ANTIGUA ST JOHNNS MINISTRY OF EDUCATION ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES EXO ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES EXO ARGENTINA LA LUCILA ASOCIACION ESCUELAS LINCOLN ARMENIA YEREVAN AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA ARMENIA YEREVAN GARIK ARAKELYAN PE AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE MELBOURNE INT'L GRADUATE COLLEGE AUSTRALIA SOUTHPORT FOREST HEIGHTS ACADEMY AUSTRALIA SYDNEY PARKUS TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA SYDNEY SYNERGY TRAINING AND CONSULTING PTY LTD AUSTRIA VIENNA SEMIZEN EDV GMBH BAHAMAS ELEUTHERA CENTRAL ELEUTHRA HIGH SCHOOL BAHAMAS FREEPORT LUCAYA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BAHAMAS FREEPORT TABERNACLE BAPTIST CHRISTIAN ACADEMY BAHAMAS NASSAU TEMPLE CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL BAHAMAS NASSAU UNIV OF THE BAHAMAS BAHRAIN AL MAZROWIAH RIFFA VIEWS INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL (CONNECME) BAHRAIN MANAMA CAPITAL SCHOOL BAHRAIN (CONNECME) BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - DHANMONDI BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - UTTARA BARBADOS ST JOHN THE CODRINGTON SCHOOL BELARUS MINSK STREAMLINE LANGUAGE SCHOOL BELGIUM BRUSSELS XCUELA - XCONIFY ACADEMY BELIZE BELIZE CITY SAINT JOHN'S COLLEGE BENIN COTONOU EPS - LA CITE UNIVERSITY BERMUDA PAGET BERMUDA COLLEGE BERMUDA SOUTHAMPTON BERMUDA INSTITUTE OF SDA BOLIVIA COCHABAMBA AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BOLIVIA LA PAZ AMERICAN COOPERATIVE SCHOOL BOLIVIA SANTA CRUZ SANTA CRUZ COOPERATIVE SCHOOL BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE CULTURA INGLESA BELO HORIZONTE BRAZIL BRASILIA CASA THOMAS JEFFERSON - FILIAL SUDOESTE -

13Th September, 2019 Issue 18

Day BASKETBALL CAMP THIS ISSUE 6th September, 2014 Issue No. 13- 1 2014– 2015 Term 1 Week 1 Head of school with her two deputies 1 IN THIS BULLETIN THIS ISSUE Page 2 – Message from Headteacher; Alumni News th Page 3 – Middle School; Music Notices; Ski Trip 13 September, 2019 Page 4 – IJSO Page 5 – Sixth Form; Exam Results; Food Trip Page 6 – Zanzibar Photos Issue 18 – 1 Page 7 – Hospice Walk info Page 8 – MSMUN; Debating Term 1 Page 9 – Inspiration from Learning Support Page 10 – Sports Notices Page 11 – Swimming Week 2 Page 12 – Boys Football; Hockey Page 13 – Girls Basketball; Gym Timings; Calendar Kenya Girls’ Swimming team Mr. John Eveson Headteacher 0786 888 890 [email protected] Mrs. Razwana Kimutai Deputy Headteacher 0710 540 079 [email protected] Ms. Tiffaney Algar Deputy Headteacher 0717 041 506 [email protected] Mr. Maurice Otieno Head of Senior School 0722 740 795 [email protected] Ms. Jane Akelola Head of Middle School 0733 714 579 [email protected] Mrs. Kira Channa Head of Junior School 0723 688 666 [email protected] MESSAGE FROM THE HEADTEACHER . This academic year should be an even more vibrant and dynamic one! We have a large number of new staff (see the list in my letter issued last week) and many more students from GEMS and elsewhere. Team building, which is ongoing, began with team building challenges for the staff on Wednesday 28th August. Some highlights are in the images below. Last Saturday the Sixth Form Bonding event opened a series of these for students too. -

Laws of Kenya

LAWS OF KENYA THE RATING ACT CHAPTER 267 Revised Edition 2010 (1986) Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney General www.kenyalaw.org 2 CAP. 267 Rating [Rev. 2010 CHAPTER 267 THE RATING ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1—Short title. 2—Interpretation. 3—Duty to levy rates. 4—Forms of rating. 5—Alternative methods of area rating. 6—Site value and improvement rates. 7—Appointment of valuer. 8—Supplementary rate. 9—Special rate. 10—Uniformity of rate. 11—Areas chargeable with rates. 12—Equitable distribution of rates. 13—Rating in areas of urban, area and local councils. 14—Fees for collection of rates on behalf of urban, area and local councils. 15—Notice of rate to be published and valuation roll to be conclusive. 16—Payment of rates discount and interest. 17—Enforcement of payment of rate. 18—Recovery of rates from tenants or occupiers. 19—Rates chargeable on property. 20—Rateable owners liable for rates. 21—Statement of payment of rates and other charges. 22—Exemption from, and remission of, rates. 23—Contribution in lieu of rates. 24—Evidence. 25—Jurisdiction of magistrates. 26—Publication and service of notices, etc. 27—Power to make rules. 28—Saving. SCHEDULES. Rev. 2010] Rating CAP. 267 3 CHAPTER 267 20 of 1964, L.N. 39/1965, THE RATING ACT L.N. 264/1965, 7 of 1968, Commencement: 12th December, 1963 6 of 1977, 11 of 1992, An Act of Parliament to provide for the imposition of rates on land and 8 of 1997. buildings in Kenya; to amend the law relating to valuation and rating in Kenya; and for purposes connected therewith and incidental thereto 1. -

2Nd March, 2018 Issue 16

Mr Leon Bareham Headteacher 0733 800 155 [email protected] Ms. Lucy Darwin Deputy Headteacher Pastoral 0734 700605 [email protected] Mr. Peter Wairi Deputy Headteacher Admin [email protected] Mr. Duncan Gowen Deputy Headteacher Academic [email protected] Mr. Chris Starling Deputy Headteacher Co- Curricular School Contacts 020 8067783/4, 020 2662137/8, 0724 255444 Hillcrest students at President’s Award Hiking/Camping weekend 20 IN THIS BULLETIN THIS ISSUE Page 2 – Head Teacher’s message; Alumni 2nd March, 2018 Page 3 – Board of Governors’ message; Deputy Head Page 5 – Inspiration from the Hexagon Issue 16 – 20 Page 7 – Junior School; Middle School Pages 8 and 9 – President’s Award Expedition Term 2 Page 10 - EAMUN Page 11 – Sixth Form; Music News Week 8 Pages 12 and 13 – Girls’ Hockey; Swimming Page 14 – Boys’ Hockey; Events U15 Boys’ Hockey team who won the Peponi Tournament last weekend Mr. John Eveson Head Teacher 0786 888 890 [email protected] Mrs. Razwana Kimutai Deputy Headteacher 0710 540 079 [email protected] Ms. Tiffaney Algar Deputy Headteacher 0717 041 506 [email protected] Mr. Maurice Otieno Head of Senior School 0722 740 795 [email protected] Ms. Jane Akelola Head of Middle School 0733 714 579 [email protected] Mrs. Kira Channa Head of Junior School 0723 688 666 [email protected] . MESSAGE FROM THE HEAD TEACHER Congratulations must go to our U15 boys who won the Hockey Tournament last week at Peponi School. -

Espresso December 2015

Nairobi International school ESPRESSO December 2015 From the Director’s Desk Dear Parents Thank God another term is over! I can only sigh in relief as I pen these few lines to you. Looking after youngsters is no easy task and it requires loads of energy and patience, needless to say understanding and unconditional love too! I am just grateful that we managed to end yet another long term without any incidents that left any sour taste in our mouths and minds. Each day that is my prayer …to start and end the day without any upheavals, especially amongst the student body. The world we are living in today gives one night mares every single moment. As parents and teachers we can only pray and hope to give our children wisdom, guidance and strength, to take one day at a time. As we rest and reflect on the bygone days, here is something for you to think about for the future. We have been offering ‘Parent Teacher Consultations’ once a term, but I feel there is need for more involvement from the parents in the school. Towards this we are planning to have year group socials each term where you will be invited to a coffee evening and this is a forum where you can socialize and exchange ideas while attending workshops on parenting. From what we have noticed, there is definite need for this. The dates for such socials will be in the calendar that will be coming to you on the first day of school and I would appreciate if you were to make a note of the ones concerning you as a parent at NIS and attend the socials without fail. -

Amazing Kenya Relocation Guide

AMAZING KENYA - WELCOME BOOKLET Relocation Guide for United Nations Secretariat Staff & Families THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE IN NAIROBI (UNON) Credits: Written and designed by Karla Rodriguez Harvey ([email protected]) in coordination with UNON Staff Development and Training Unit ([email protected]) Cover Photography by Dietmar Temps ([email protected]) May 2016 CONTENTS Visiting Kenya ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Nairobi at glance ............................................................................................................................... 8 Where to stay ...................................................................................................................................... 1 What to do ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Travel in Kenya .................................................................................................................................... 6 Dining.................................................................................................................................................... 7 Airport - Transportation ...................................................................................................................... 8 Car Rental ........................................................................................................................................... -

Rosslyn Academy Middle School Student Handbook 2020

Rosslyn Academy Middle School Student Handbook 2020 - 2021 Off Limuru Road Off Unep Avenue Past Unep. Off Magnolia Close Gigiri Nairobi, Kenya Mailing Address: P.O. Box 14146-00800, Nairobi, Kenya School Phone Numbers: +254-20-263-5294/5295/5296/5261 Cell Phone: +254-732-646-602 or +254-727-646-602 Office Hours: 8:30-4:00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rosslynacademy.com 1 Letter from your MS Principal Summer 2020 Theme Verse 2020-2021: I Peter 4:10 “Each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms.” (NIV) As we begin this new school year in a challenging situation, my prayer for the Middle School is for every student and teacher to come to realize their particular gifts given to them by God and to share them and use them for service to one another and for His glory. Beginning the year with VLE will bring its challenges, but my hope is that we can find unique and creative ways to give to one another and support one another in spite of our circumstances. As a middle school, we can become a community where we serve and love each other well. I am so thankful for each and every one of you and the specific gifts you bring to our middle school community! Ms. Heather Schneider Middle School Principal 2 Contents Letter from your MS Principal 2 Statement of Support 7 Middle School 2018-2019 Calendar 9 Middle School Bell Schedule 10 History and Organization 11 Governance 11 Accreditation 11 Educational Philosophy 12 What is Middle School (Grades 6-8)? 12 -

Rosslyn Academy Middle School Student Handbook 2019

Rosslyn Academy Middle School Student Handbook 2019 - 2020 Off Limuru Road Off Unep Avenue Past Unep. Off Magnolia Close Gigiri Nairobi, Kenya Mailing Address: P.O. Box 14146-00800, Nairobi, Kenya School Phone Numbers: +254-20-263-5294/5295/5296/5261 Cell Phone: +254-732-646-602 or +254-727-646-602 Office Hours: 8:30-4:00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rosslynacademy.com 1 Letter from your MS Principal Summer 2019 Theme Verse 2019-2020: John 8:12, “Jesus said, ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the light of life.’” (NIV). As we begin this new school year, my prayer for the Middle School is that every student and teacher seeks to understand and pursue Jesus as the light of our life. We all of secret parts our life that we would rather now come to light. Things that the people that know us best don’t even know. The reality is, God knows. He doesn’t want our sins to come out so he can shame us, He wants to shine his light on our hearts to purify our lives and transform us in to vessels that pour out His love on others. I am praying for each and every one of us to be living our lives in the Light of Christ this year! Mr. Tyler Heugel Middle School Principal 2 Contents Letter from your MS Principal 2 Statement of Support 7 Middle School 2018-2019 Calendar 9 Middle School Bell Schedule 10 History and Organization 11 Governance 11 Accreditation 11 Educational Philosophy 12 What is Middle School (Grades 6-8)? 12 Middle School Objectives 12 General Objectives 12 Spiritual Objectives -

2018-2019 ACT International Test Centers Test Centers Are Subject to Change

2018-2019 ACT International Test Centers Test centers are subject to change. To see the most current list, please visit http://my.act.org and begin the registration process for the ACT test. *Updated 8.07.18. Country City Test Center Name ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES EXO ARMENIA YEREVAN GARIK ARAKELYAN PE AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE SAXONS TRAINING FACILITIES AUSTRALIA SOUTHPORT THE SOUTHPORT SCHOOL AUSTRALIA SYDNEY SAXONS TRAINING FACILITIES AUSTRIA VIENNA SEMIZEN EDV GMBH AZERBAIJAN BAKU AZERBAIJAN MEDICAL UNIVERSITY A AZERBAIJAN BAKU AZERBAIJAN MEDICAL UNIVERSITY B Bahamas Bimini, Bah Gateway Christian Academy Bahamas FREEPORT LUCAYA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL Bahamas NASSAU TEMPLE CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL Bahamas NASSAU UNIV OF THE BAHAMAS BAHRAiN MANAMA MODERN KNOWLEDGE-CONNECME BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - DHANMONDI BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - UTTARA BARBADOS ST. MICHAEL GENESIS TRAINING SYSTEMS, INC. BELARUS MINSK STREAMLINE LANGUAGE SCHOOL BELGIUM BRUSSELS XCUELA - XCONIFY ACADEMY BELIZE BELIZE CITY SAINT JOHN'S COLLEGE BENIN COTONOU EPS - LA CITE UNIVERSITY BERMUDA PAGET BERMUDA COLLEGE BERMUDA SOUTHAMPTON BERMUDA INSTITUTE OF SDA BOLIVIA COCHABAMBA AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BOLIVIA LA PAZ AMERICAN COOPERATIVE SCHOOL BOLIVIA SANTA CRUZ BIT CONSULTING BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ILIDZA INTL UNIV OF SARAJEVO-CONNECME BRAZIL BAHIA PAN AMERICAN SCHOOL OF BAHIA BRAZIL BRASILIA, DF CASA THOMAS JEFFERSON - FILIAL SUDOESTE BRAZIL FORTALEZA UNIFOR - UNIVERSIDADE DE FORTALEZA BRAZIL MARINGA/PARANA CULTURA INGLESA MARINGA BRAZIL RECIFE PE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF RECIFE