Report Botanical Groblershoop Resort Envafr Aug 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oriental Fruit Fly) in Several District Municipalities in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa

International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) country report by the National Plant Protection Organization (NPPO) of South Africa: Notification on the detection of Bactrocera dorsalis (Oriental Fruit Fly) in several District Municipalities in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa Pest Bactrocera dorsalis (Oriental Fruit Fly) Status of pest Transient: actionable, under eradication Host or articles concerned Citrus spp., Grape (including Table-, Wine-, and Dry grape varieties); Plum, Pomegranate fruits produced or present in this area in South Africa are under threat. Geographic distribution Several male, Bactrocera dorsalis specimens, were detected in Methyl Eugenol-baited traps between Douglas and Prieska, situated approximately 300 km East of Upington as well as in Groblershoop, Karos, Upington, Kakamas and Augrabies, areas alongside or close to the Orange River, in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. Other male detections occurred in Jan Kempsdorp, which is approximately 400km from North-West of Upington. Nature of immediate or Potential spread or establishment of B.dorsalis into other production potential danger areas where its presence may impede the export potential of the relevant host commodities affected. Summary Several male, Bactrocera dorsalis specimens, were detected in Methyl Eugenol-baited traps from Douglas to Kakamas, areas alongside or close to the Orange River, in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. Four specimens were collected from Douglas and two specimens from Prieska, situated approximately 300 km West of Upington, where wine grapes are produced. In Groblershoop, also an area of wine and dry grapes production, approximately 110 km from Upington, two specimens were detected. Two specimens were detected in Karos, situated 50 km West of Groblershoop. -

Major Vegetation Types of the Soutpansberg Conservancy and the Blouberg Nature Reserve, South Africa

Original Research MAJOR VEGETATION TYPES OF THE SOUTPANSBERG CONSERVANCY AND THE BLOUBERG NATURE RESERVE, SOUTH AFRICA THEO H.C. MOSTERT GEORGE J. BREDENKAMP HANNES L. KLOPPER CORNIE VERWEy 1African Vegetation and Plant Diversity Research Centre Department of Botany University of Pretoria South Africa RACHEL E. MOSTERT Directorate Nature Conservation Gauteng Department of Agriculture Conservation and Environment South Africa NORBERT HAHN1 Correspondence to: Theo Mostert e-mail: [email protected] Postal Address: African Vegetation and Plant Diversity Research Centre, Department of Botany, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0002 ABSTRACT The Major Megetation Types (MVT) and plant communities of the Soutpansberg Centre of Endemism are described in detail, with special reference to the Soutpansberg Conservancy and the Blouberg Nature Reserve. Phytosociological data from 442 sample plots were ordinated using a DEtrended CORrespondence ANAlysis (DECORANA) and classified using TWo-Way INdicator SPecies ANalysis (TWINSPAN). The resulting classification was further refined with table-sorting procedures based on the Braun–Blanquet floristic–sociological approach of vegetation classification using MEGATAB. Eight MVT’s were identified and described asEragrostis lehmanniana var. lehmanniana–Sclerocarya birrea subsp. caffra Blouberg Northern Plains Bushveld, Euclea divinorum–Acacia tortilis Blouberg Southern Plains Bushveld, Englerophytum magalismontanum–Combretum molle Blouberg Mountain Bushveld, Adansonia digitata–Acacia nigrescens Soutpansberg -

Ncta Map 2017 V4 Print 11.49 MB

here. Encounter martial eagles puffed out against the morning excellent opportunities for river rafting and the best wilderness fly- Stargazers, history boffins and soul searchers will all feel welcome Experience the Northern Cape Northern Cape Routes chill, wildebeest snorting plumes of vapour into the freezing air fishing in South Africa, while the entire Richtersveld is a mountain here. Go succulent sleuthing with a botanical guide or hike the TOURISM INFORMATION We invite you to explore one of our spectacular route and the deep bass rumble of a black- maned lion proclaiming its biker’s dream. Soak up the culture and spend a day following Springbok Klipkoppie for a dose of Anglo-Boer War history, explore NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Discover the heart of the Northern Cape as you travel experiences or even enjoy a combination of two or more as territory from a high dune. the footsteps of a traditional goat herder and learn about life of the countless shipwrecks along the coast line or visit Namastat, 15 Villiers Street, Kimberley CBD, 8301 Tel: +27 (0) 53 833 1434 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 along its many routes and discover a myriad of uniquely di- you travel through our province. the nomads. In the villages, the locals will entertain guests with a traditional matjies-hut village. Just get out there and clear your Traveling in the Kalahari is perfect for the adventure-loving family Email: [email protected] verse experiences. Each of the five regions offers interest- storytelling and traditional Nama step dancing upon request. mind! and adrenaline seekers. -

Outdoor Education & Sports Centre

OUTDOOR EDUCATION & SPORTS CENTRE INFO LEAFLET Make the outdoors your new classroom! Youth – Adventure – Fun – Leadership – Sport WELCOME AT DUIN IN DIE WEG OUTDOOR EDUCATION AND SPORTS CENTRE DUIN IN DIE WEG Who we are Outdoor education - Sport - Accommodation - Conferences & functions DUIN IN DIE WEG is a guest farm with an established Outdoor Education and Sports Centre, catering primarilly for the school going youth. We also offer excellent accommodation and programmes for various groups, tourists, and have facilities for conferences and functions. Our aim is to please each of our guests with an unforgettable experience by the time they leave us. Where can you find us? DUIN IN DIE WEG is located along the Orange River, 2 kilometers from the N10, between Upington and Groblershoop. The name is derived from our particular environment, being one of the few places where the Kalahari dunes and the Orange River meet. In the earlier years, after windy conditions, sand was blown over and covered the roads in the area, hence the dune in the road. The farm encapsulates all the contrasts of the beautiful Northern Cape – from the Kalahari dunes to the great green belt along the Orange river. This is a truly unique place where different ecosystems come together. What we do Being located on a privately owned farm that comprises over 2000 hectares, it is the perfect destination for outdoor education. Our outdoor educational and sport programmes are appropriately designed to fit different groups and focus on the environment, adventure, fun, leadership and sport. We cater for all grades, schools, teams and other groups. -

Training of Trainers Curriculum

TRAINING OF TRAINERS CURRICULUM For the Department of Range Resources Management on climate-smart rangelands AUTHORS The training curriculum was prepared as a joint undertaking between the National University of Lesotho (NUL) and World Agroforestry (ICRAF). Prof. Makoala V. Marake Dr Botle E. Mapeshoane Dr Lerato Seleteng Kose Mr Peter Chatanga Mr Poloko Mosebi Ms Sabrina Chesterman Mr Frits van Oudtshoorn Dr Leigh Winowiecki Dr Tor Vagen Suggested Citation Marake, M.V., Mapeshoane, B.E., Kose, L.S., Chatanga, P., Mosebi, P., Chesterman, S., Oudtshoorn, F. v., Winowiecki, L. and Vagen, T-G. 2019. Trainer of trainers curriculum on climate-smart rangelands. National University of Lesotho (NUL) and World Agroforestry (ICRAF). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This curriculum is focused on training of trainer’s material aimed to enhance the skills and capacity of range management staff in relevant government departments in Lesotho. Specifically, the materials target Department of Range Resources Management (DRRM) staff at central and district level to build capacity on rangeland management. The training material is intended to act as an accessible field guide to allow rangeland staff to interact with farmers and local authorities as target beneficiaries of the information. We would like to thank the leadership of Itumeleng Bulane from WAMPP for guiding this project, including organising the user-testing workshop to allow DRRM staff to interact and give critical feedback to the drafting process. We would also like to acknowledge Steve Twomlow of IFAD for his -

NC Sub Oct2016 ZFM-Keimoes.Pdf

# # !C # # ### !C^# !.!C# # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # #!C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # ^ # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # #^ # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # ##^ # !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # #!C # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # ## # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # !C # # # ## #!C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # ## # !C# # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # ## # # # # # # !C # ## # !C # # # # !C # ## !C # # # # # # !C # !.# # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # !C # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # ### # #^ # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C ## # # # # # ^ # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # ## ## # !C## !C## # # # !C # # # # ## # !C # # # ^ # # !C ### # # # !C# # #!C # !C # # ^ ## #!C ### # # !C # # # # # # # # ## # ## ## # # # # !C # # # # ## # # # # #!C # ## # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # ## # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C# !. # # !C# ### # # # # # # -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

Grasses of Namibia Contact

Checklist of grasses in Namibia Esmerialda S. Klaassen & Patricia Craven For any enquiries about the grasses of Namibia contact: National Botanical Research Institute Private Bag 13184 Windhoek Namibia Tel. (264) 61 202 2023 Fax: (264) 61 258153 E-mail: [email protected] Guidelines for using the checklist Cymbopogon excavatus (Hochst.) Stapf ex Burtt Davy N 9900720 Synonyms: Andropogon excavatus Hochst. 47 Common names: Breëblaarterpentyngras A; Broad-leaved turpentine grass E; Breitblättriges Pfeffergras G; dukwa, heng’ge, kamakama (-si) J Life form: perennial Abundance: uncommon to locally common Habitat: various Distribution: southern Africa Notes: said to smell of turpentine hence common name E2 Uses: used as a thatching grass E3 Cited specimen: Giess 3152 Reference: 37; 47 Botanical Name: The grasses are arranged in alphabetical or- Rukwangali R der according to the currently accepted botanical names. This Shishambyu Sh publication updates the list in Craven (1999). Silozi L Thimbukushu T Status: The following icons indicate the present known status of the grass in Namibia: Life form: This indicates if the plant is generally an annual or G Endemic—occurs only within the political boundaries of perennial and in certain cases whether the plant occurs in water Namibia. as a hydrophyte. = Near endemic—occurs in Namibia and immediate sur- rounding areas in neighbouring countries. Abundance: The frequency of occurrence according to her- N Endemic to southern Africa—occurs more widely within barium holdings of specimens at WIND and PRE is indicated political boundaries of southern Africa. here. 7 Naturalised—not indigenous, but growing naturally. < Cultivated. Habitat: The general environment in which the grasses are % Escapee—a grass that is not indigenous to Namibia and found, is indicated here according to Namibian records. -

Join Us for a Family & Friends Weekend!

An amazing adventure between dunes & river! JOIN US FOR A FAMILY & FRIENDS WEEKEND! JOIN US FOR YOUR NEXT ADVENTURE! An unforgettable experience! Come, join us on an adventure, leave only footprints and take away lasting memories... WELCOME! A whole weekend of living in the best of nature – affordable accommodation, good meals, canoeing and hiking. Hiking and canoeing is not only good for inner being, it is also a great healthy activity. We take you out of your comfort zone and into a place where you will connect with nature, your friends & family, and most importantly, with yourself... We want to add more meaning, adventure, memories and experiences. EXPERIENCE THIS… - Wake up with tunes of early morning bird-song and nature - Canoeing on the serene Orange River … fresh air in your face; an outing promising the soul food of awe-inspiring views - Walk / hike in the open veld or next to the Orange river – experiencing the breath-taking natural beauty of the Kalahari - Do special activities like a tractor trip in the veld or Orange river fishing with special friends - You can sleep in a tent or next to the fire in the open air. One of the few places left where this can be done - Sit around the camp fire at night enjoying each other’s company - Share sunrises and sunsets together COME AND HAVE THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE! We really hope you will depart home with a sense of achievement and well-being. New friendships will have been established and existing friendships and family relationships will have been renewed. -

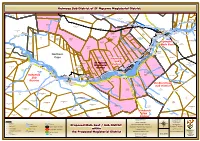

Groblershoop, Grootdrink, Kakamas, Keimoes, Upington

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 STAATSKOERANT, 15 NOVEMBER 2019 No. 42840 89 NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION NO. R. 1488 15 NOVEMBER 2019 R. 1488 Wine of Origin Scheme: Notice of application for the defining of production areas (wards): Groblershoop, Grootdrink, Kakamas, Keimoes, Upington and amendment of Central Orange River Ward to a District 42840 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR THE DEFINING OF PRODUCTION AREAS (WARDS) GROBLERSHOOP, GROOTDRINK, KAKAMAS, KEIMOES, UPINGTON AND AMENDMENT OF CENTRAL ORANGE RIVER WARD TO A DISTRICT ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (In terms of Section 6 of the Wine of Origin Scheme published by Government Notice No. R.1434 of 29 June 1990) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Please take note that Orange Rivier Cellars applied to the Wine and Spirit Board to define Groblershoop, Grootdrink, Kakamas, Keimoes and Upington as production areas (Wards) to produce Wine of Origin. Central Orange River District, consists of a 5km buffer strip, on both sides of the Orange River and extends from Boegoeberg Dam to the Augrabies waterfalls (a distance of about 275 kilometers), has been changed from a Ward to a District to accommodate new wards. The proposal is to divide the District into five Wards, namely: • Groblershoop Ward: The Ward extends from the Boegoeberg Dam embankment, downstream to Kalkwerf. Topography was used to distinguish it from the Grootdrink Ward. • Grootdrink Ward: The Ward extends from Kalkwerf to Leerhoek, just before the Rooikoppe. • Upington Ward: From Leerhoek, the Ward extends and includes the town Upington just before Kanoneiland. • Keimoes Ward: The upper boundary runs perpendicular to the river just above Kanoneiland and ends on the Neusbergrif at the weir of the Neus. -

Olympus AH Eco Assessment

FLORAL AND GENERAL ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED RELOCATION OF THE DINGLETON TOWN WITH ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE TO THE FARM SEKGAME 461 EAST OF KATHU WITHIN THE NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Prepared for Synergistics Environmental Services (Pty) Ltd 2012 Prepared by: Scientific Aquatic Services Report author S. van Staden (Pr. Sci. Nat) N. van de Haar (Pr.Sci. Nat) Report Reference: SAS 212055 Date: May 2012 Scientific Aquatic Services CC CC Reg No 2003/078943/23 Vat Reg. No. 4020235273 Cape Town Tel: 078 220 8571 082 866 9849 E-mail: [email protected] SAS 212055 – Floral Assessment May 2012 Declaration This report has been prepared according to the requirements of Section 33 (2) of the Environmental Impact Assessments Regulations, 2006 (GNR 385). We (the undersigned) declare the findings of this report free from influence or prejudice. Report Authors: Stephen van Staden Pr Sci Nat (Ecological Sciences) 400134/05 BSc. Hons (Aquatic Health) (RAU); M.Sc. Environmental Management (RAU). Field of expertise: Wetland, aquatic and terrestrial ecology. ___________________ Date:_ 02/04/2012___ Stephen van Staden Natasha van de Haar Pr Sci Nat (Botanical Science) 400229/11 M.Sc. Botany Field of expertise: Botanical specialist ___________________ Date:_ 02/04/2012___ Natasha van de Haar ii SAS 212055 – Floral Assessment May 2012 Executive summary Scientific Aquatic Services (SAS) was appointed to conduct a floral and general ecological assessment for the proposed relocation of the Dingleton town along with associated infrastructure to the farm Sekgame 461 east of the town of Kathu within the Northern Cape Province. Two areas were investigated as part of this assessment namely the existing Dingleton Town with surroundings as well as the proposed host site located on the farm Sekgame 461. -

NC Sub Oct2016 ZFM-Postmasburg.Pdf

# # !C # ### # ^ #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C # # # # # ## # #!C# # # # # # #!C # # ^ ## # !C# # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # # ^ !C # # # ^# # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # !C # # # !C# ## # !C# # ## # # # # #!C # # # #!C##^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# ## ## # ## # # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## #!C ## # ## # # !C### # # # # # # # # # # # # !C## # # ## #!C # # # ##!C# # # # ##^# # # # # ## ###!C# # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # ## # # ## !C# #^ # #!C # # !C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # ### # # ## ## # # # # ### ## ## # # # # !C# # !C # # # #!C # # # #!C# ### # #!C## # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # ## ## # # ## # # ## # # # # # # ## ### ## # ##!C # ## # # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ ## # #### ## # # # # # # #!C# # ## # ## #!C## # #!C# ## # # !C# # # ##!C#### # # ## # # # # # !C# # # # ## ## # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## ## ##!C### # # # # # !C # !C## #!C # !C # #!.##!C# # # # ## # ## ## # # ### #!C# # # # # # # ## ###### # # ## # # # # # # ## ## #^# ## # # # ^ !C## # # !C# ## # # ### # # ## # ## # # ##!C### ##!C# # !C# ## # ^ # # # !C #### # # !C## ^!C#!C## # # # !C # #!C## #### ## ## #!C # ## # # ## # # # ## ## ## !C# # # # ## ## #!C # # # # !C # #!C^# ### ## ### ## # # # # # !C# !.### # #!C# #### ## # # # # ## # ## #!C# # # #### # #!C### # # # # ## # # ### # # # # # ## # # ^ # # !C ## # # # # !C# # # ## #^ # # ^ # ## #!C# # # ^ # !C# # #!C ## # ## # # # # # # # ### #!C# # #!C # # # #!C # # # # #!C #!C### # # # # !C# # # # ## # # # # # # # #