A Teacher's Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honoring Grace and Chuck Tolson

Autumn 2014 & Autumn Classes Catalogue The Journal of the San Geronimo Valley Community Center had three children, Barbara, Chalmer and David Tolson. Chuck and Grace Honoring Grace and first met in 1961 through Grace’s brother Mel who worked with Chuck as a mechanic. They didn’t see each other for over ten years, but after their first marriages ended Chuck and Grace became a couple. Today they have four Chuck Tolson children, two foster sons, twelve grandchildren, and two great grandchildren. By Dave Cort and Carol Rebscher Grace always loved horses and she began teaching other children to ride when she was thirteen years old. Together Grace and Chuck manage the Dickson This year at the Community Center’s Annual Gala on September Ranch and run eight horse shows 27th, we our honoring two amazing people who are heroes to so each year. In 1990 they founded many people in our San Geronimo Valley and Nicasio Valley com- Valley Toys and Joys, and every year munities. Their commitment to supporting children and families they host the Fourth of July festivities is unmatched. Every year during the winter holidays, through their at their ranch as well as major fund- organization, Valley Toys and Joys, Chuck and Grace support close raisers. For over ten years, Chuck and to 200 children in the San Geronimo Valley and Nicasio Valley by Grace hosted the Valley Visions fund- filling their holiday gift wish lists. Each gift is beautifully wrapped raiser for LEAP, the Lagunitas School th with a personalized card. Chuck and Grace are the 6 generation of Foundation. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Lecture Explores Female

C A LIFO R NI A S T A T E U NIVE RS IT Y , F U LLE R TON Jodie Cox strikes INSIDE out 16 Scarlet Knights as the 3 n NEWS: Sushi restaurants offer unique Titans begin the cuisine and community atmosphere Kia Klassic 4 n DETOUR: Nas and Jay-Z throw in their with a win. towels in the battle of lyrics —see Sports page 6 VOLU M E 73, I SSUE 14 THURSDAY M ARCH 14, 2002 Lecture explores female nSPEAKER: Artist Jacqueline Cooper presents contemporary feminist performance art Wednesday BY MICHAEL MATTER may be at CSUF but you will be negative signification of the written are still stuck trying to use exterior Daily Titan Staff Writer getting a Harvard or Scripps College word,” Cooper said. “ Arguably, a language to explain the similarities lecture.” similar spatial imperative fueled the and divisions between interior space As part of the Women’s History Cooper was born in London. She development of a performance and in both the literary and the visual Month lecture series, artist, author earned her master’s degree from installation art practice increasingly arts. and social critic Jacqueline Cooper, UCLA in 1998 and has taught at apparent since the emergence of Cooper’s opening video presenta- offered a multimedia presentation Santa Monica College and Long the women’s movement in the late tion showed three separate women titled “(Re)Presenting the Feminist Beach City College. 1960s.” sitting on stools facing the audi- Vision,” at the Titan Theatre She has also taught at UCLA and Cooper suggested that perfor- ence. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Radio Starz Karaoke Song Book

Radio Starz Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Aerosmith Barenaked Ladies Angel RSZ613-12 What A Good Boy RSZ604-11 Baby, Please Don't Go RSZ613-01 When I Fall RSZ604-09 Back In The Saddle RSZ613-16 Beatles, The Big Ten Inch Record RSZ613-13 All You Need Is Love RSZ623-08 Cryin' RSZ613-17 And I Love Her RSZ623-06 Dream On RSZ613-04 And Your Bird Can Sing RSZ622-17 Dude (Looks Like A Lady) RSZ613-06 Another Girl RSZ621-16 I Don't Want To Miss A Thing RSZ613-10 Back In The USSR RSZ622-02 Jaded RSZ613-07 Birthday RSZ622-05 Janie's Got A Gun RSZ613-14 Can't Buy Me Love RSZ622-09 Last Child RSZ613-03 Come Together RSZ621-14 Love In An Elevator RSZ613-09 Day Tripper RSZ621-07 Mama Kin RSZ613-11 Do You Want To Know A Secret RSZ623-11 Same Old Song And Dance RSZ613-15 Don't Let Me Down RSZ623-09 Sweet Emotion RSZ613-05 Eight Days A Week RSZ623-05 Train Kept A Rollin' RSZ613-18 Eleanor Rigby RSZ622-13 Walk This Way RSZ613-08 From Me To You RSZ623-15 What It Takes RSZ613-02 Get Back RSZ622-04 Alanis Morissette Golden Slumbers, Carry That Weight, The End RSZ621-20 All I Really Want RSZ626-13 Good Day Sunshine RSZ621-06 Everything RSZ626-11 Hard Days Night, A RSZ623-03 Forgiven RSZ626-12 Hello Goodbye RSZ622-06 Hand In My Pocket RSZ626-05 Help! RSZ621-04 Hands Clean RSZ626-08 Helter Skelter RSZ622-08 Hands Clean RSZ626-08A Here, There & Everywhere RSZ623-18 Hands Clean RSZ626-08B Hey Jude RSZ622-01 Head Over Feet RSZ626-07 I Feel Fine RSZ622-10 Ironic RSZ626-02 I Saw Her Standing There RSZ621-01 Precious Illusions -

Catalogue Karaoke

CHANSONS ANGLAISES A A A 1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE NO MORE SAME OLD BRAND NEW YOU Aallyah THE ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO Aaliyah & Timbaland WE NEED A RESOLUTION Abba CHIQUITITA DANCING QUEEN KNOWING ME AND KNOWING YOU MONEY MONEY MONEY SUPER TROUPER TAKE A CHANCE ON ME THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Ace of Base ALL THAT SHE WANTS BEAUTIFUL LIFE CRUEL SUMMER DON'T TURN AROUND LIVING IN DANGER THE SIGN Adrews Sisters BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGLE BOY Aerosmith I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING SAME OLD SONG AND DANCE Afroman BECAUSE I GOT HIGH After 7 TILL YOU DO ME RIGHT Air Supply ALL OUT OF LOVE LOST IN LOVE Al Green LET'S STAY TOGETHER TIRED OF BEING ALONE Al Jolson ANNIVERSARY SONG Al Wilson SHOW AND TELL Alabama YOU'VE GOT THE TOUCH Aladdin A WHOLE NEW WORLD Alanis Morissette EVERYTHING IRONIC PRECIOUS ILLUSIONS THANK YOU Alex Party DON'T GIVE ME YOUR LIFE Alicia Keys FALLIN' 31 CHANSONS ANGLAISES HOW COME YOU DON'T CALL ME ANYMORE IF I AIN'T GOT YOU WOMAN'S WORTH Alison Krauss BABY, NOW THAT I'VE FOUND YOU All 4 One I CAN LOVE YOU LIKE THAT I CROSS MY HEART I SWEAR All Saints ALL HOOKED UP BOTIE CALL I KNOW WHERE IT’S AT PURE SHORES Allan Sherman HELLO MUDDUH, HELLO FADDUH ! Allen Ant Fam SMOOTH CRIMINAL Allure ALL CRIED OUT Amel Larrieux FOR REAL America SISTER GOLDEN HAIR Amie Stewart KNOCK ON WOOD Amy Grant BABY BABY THAT'S WHAT LOVE IS FOR Amy Studt MISFIT Anastacia BOOM I'M OUTTA LOVE LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE MADE FOR LOVING YOU WHY'D YOU LIE TO ME Andy Gibb AN EVERLASTING LOVE Andy Stewart CAMPBELTOWN LOCH Andy Williams CAN'T GET USED TO LOSING YOU MOON RIVER -

Christmas O Christmas Tree Christmas O Come All Ye Faithful

Christmas O Christmas Tree Christmas O come All Ye Faithful Christmas O Come O Come Emmanuel Celine Dion O Holy Night Christmas O Holy Night Tevin Campbell O Holy Night Christmas O Little Town of Bethlehem Christmas O Tannenbaum Shakira Objection Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da Animotion Obsession Frankie J. & Baby Bash Obsession (No Es Amor) [Karaoke] Christina Obvious Yellowcard Ocean Avenue Billie Eilish Ocean Eyes Billie Eilish Ocean Eyes George Strait Ocean Front Property Bobbie Gentry Ode To Billy Joe Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Cranberries Ode To My Family Alabama Of Course I'm Alright Michael Jackson Off The Wall Lana Del Rey Off To The Races Dave Matthews Oh Buddy Holly Oh Boy Neil Sedaka Oh Carol Shaggy Oh Carolina Beatles Oh Darling Madonna Oh Father Paul Young Oh Girl Sister Act Oh Happy Day Larry Gatlin Oh Holy Night Vanessa Williams Oh How The Years Go By Ulf Lundell oh la la Don Gibson Oh Lonesome Me Brad Paisley & Carrie Underwood Oh Love (Duet) Diamond Rio Oh Me Oh My Sweet Baby Stampeders Oh My Lady Roy Orbison Oh Pretty Woman Ready For the world Oh Sheila Steve Perry Oh Sherrie Childrens Oh Susanna Blessed Union of Souls Oh Virginia Frankie Valli Oh What A Night (December '63) Big Tymers & Gotti & Boo & Tateeze Oh Yeah! [Karaoke] Wiseguys Ohh la la Linda Ronstadt Ohhh Baby Baby Crosby Stills Nash and Young Ohio Merle Haggard Okie From Muskogee Billy Gilman Oklahoma [Karaoke] Reba McEntire and Vince gill Oklahoma Swing Eagles Ol 55 Randy Travis Old 8X10 Brad Paisley Old Alabama Kenny Chesney Old Blue Chair Jim Reeves Old Christmas Card Nickelback Old Enough Three Dog Night Old Fashioned Love Song Alabama Old Flame Dolly Parton Old Flames Can't Hold A Candle To You Mark Chesnutt Old Flames Have New Names Phil Stacey Old Glory Eric Clapton Old Love Childrens Old MacDonald Hootie and the Blowfish Old Man & Me Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Tanya Tucker Old Weakness George Micheal Older Cherie Older Than My Years Trisha Yearwood On A Bus To St. -

To Alanis Morissette, After Reading About Her Postpartum Depression in My Therapist's Waiting Room

TR 05 To Alanis Morissette, After Reading About Her Postpartum Depression in My Therapist’s Waiting Room Alanis Morissette Julia C. Alter “Precious Illusions” You’ll rescue me, right? Under Rug Swept 02/2002 I’ve replaced water with iced coffee. I only sweat Maverick, Warner Bros. when I sleep. Nothing happens in my dreams. I am dead weight in that specific sea, that shifty gray gnawing. Your hair is platinum now, Alanis, but I see your roots, the dark truth spreading over your story. I know how we become unrecognizable. I wore a black maxi dress with grotesque flowers all summer so I wouldn’t come looking for myself. They put you on a beach in that blue and white muumuu, strategically positioned your kids in front of your belly, juxtaposed it with a picture of you ten years ago, maybe twenty, in a white tanktop, wild hair waving onstage. They want your confession but not your flesh. They would rather have you in a muumuu, only your forearms exposed. Hands and wrists taut from lifting the baby. They can’t see the carpal tunnel from nursing, the nerve damage from gripping the toilet seat in the heaviest waves of labor. You’ll complete me, right? Alanis, I know the panic of sensing the baby stirring 11 TR 05 · Julia Alter · To Alanis Morissette, After Reading About Her Postpartum Depression in My Therapist’s Waiting Room out of his nap, what it is to click him back into his car seat for the third time in one afternoon, to ride around the block again so he will just keep sleeping. -

Alphabetical Order by Artist Big Hammer Music Entertainment 701

Alphabetical Order by Artist Big Hammer Music Entertainment Alphabetical Order by Song Title 701-840-9337 Artist Disc # Song Title Artist Disc # Song Title 112 SC 426-05 CUPID Spears, Britney CB 1101-02 3 311 PH 325-09 ALL MIXED UP Swift, Taylor PT 1403-12 22 311 SC 794-14 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE Smashing Pumpkins PH 325-08 33 702 SC 985-02 GET IT TOGETHER Beach Boys SC 165-11 409 702 SC 352-14 WHERE MY GIRLS AT? Phoenix PH 1073-05 1901 10,000 Maniacs MS 813-04 BECAUSE THE NIGHT Blunt, James CB 1034-04 1973 10,000 Maniacs SC 913-05 BECAUSE THE NIGHT Smashing Pumpkins TH 315-01 1975 10,000 Maniacs DK 961-08 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS Bowling for Soup AS 1002-05 1985 10,000 Maniacs PH 372-07 MORE THAN THIS Prince SC 142-04 1999 10,000 Maniacs SC 884-03 TROUBLE ME Estefan, Gloria PT 416-01 37623 100 Proof Aged in Soul SC 986-09 SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING Nelly SC 832-02 #1 (RADIO VERSION) 10CC SF 915-09 I'M NOT IN LOVE Garbage PH 325-07 #1 CRUSH 1910 Fruitgum Co. LC 183-14 SIMON SAYS Garbage SC 853-05 #1 CRUSH 2 Live Crew SC 375-07 ME SO … Plain White T's CB 1082-15 1 2 3 4 (I LOVE YOU) 20 Fingers SC 212-07 SHORT DICK MAN Montana, Randy CB 1203-11 1,000 FACES 21 Pilots PT 1804-03 STRESSED OUT Ciara ft. Missy Elliott AS 1002-06 1,2 STEP 3 Doors Down SC 543-07 AWAY FROM THE SUN Third Eye Blind SC 964-11 10 DAYS LATE 3 Doors Down TH 461-14 BE LIKE THAT Five For Fighting AS 573-08 100 YEARS 3 Doors Down SC 794-15 BE LIKE THAT (RADIO VERSION) Five For Fighting SC 543-10 100 YEARS 3 Doors Down SC 873-05 DUCK AND RUN Atkins, Rodney CB 1066-03 15 MINUTES 3 Doors Down SC 676-06 HERE WITHOUT YOU Dalton, Lacy J. -

Ulkomaiset Esittäjän Mukaan

• RELAX • DRINK • SING • DANCE • KARAOKE Ulkomaiset esittäjän mukaan www.esongbook.net/lista/677 Voit varata lauluvuorosi myös kännykällä! ULKOMAISET ESITTÄJÄN MUKAAN 1 / 30 ABBA Angel eyes ABBA As good as new ABBA Bang a Boomerang ABBA Chiquitita ABBA Dancing Queen ABBA Does your mother know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimmie gimmie gimmie ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Mañana ABBA Head over heels ABBA Honey honey ABBA I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA I have a dream ABBA Knowing me knowing you ABBA Lay all your love on me ABBA Mamma Mia ABBA Money, money, money ABBA One of us ABBA Ring ring ABBA Rock me ABBA S.O.S. ABBA So long ABBA Summer night city ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take a chance on me ABBA Thank you for the music ABBA The name of the game ABBA Voulez-Vous ABBA Waterloo ABBA Winner takes it all AC/DC Back in black AC/DC Dirty deeds done dirt cheap AC/DC For those about to rock AC/DC Girls got rhythm www.esongbook.net/lista/677 Voit varata lauluvuorosi myös kännykällä! ULKOMAISET ESITTÄJÄN MUKAAN 2 / 30 AC/DC Hell's bells AC/DC High voltage AC/DC Highway to hell AC/DC Jailbreak AC/DC Money talks AC/DC Shoot to thrill AC/DC Stiff upper lip AC/DC T.N.T. AC/DC Whole lotta Rosie Ace of Base All that she wants Adele Chasing pavements Adele Cold shoulder Adele Daydreamer Adele Hiding my heart Adele Hometown glory Adele Lovesong Adele Make you feel my love Adele One and only Adele Rolling in the deep Adele Rumour has it Adele Set fire to the rain Adele Someone like you Adele Turning tables Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the saddle Aerosmith Big ten inch record Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream on Aerosmith I don't want to miss a thing Aerosmith Jaded Aerosmith Janie's got a gun Aerosmith Last child Aerosmith Love in an elevator Aerosmith Mama Kin Aerosmith Same old song and dance www.esongbook.net/lista/677 Voit varata lauluvuorosi myös kännykällä! ULKOMAISET ESITTÄJÄN MUKAAN 3 / 30 Aerosmith Sweet emotion Aerosmith Train kept a rollin' Aerosmith Walk this way Aerosmith ft. -

Uniter 18 Text Corrected.Qxd

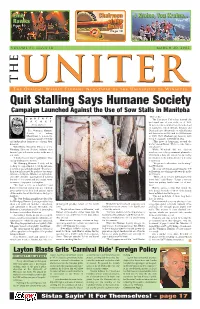

Emo Chairmen I Kraine, You Kraine... Rawks of the Page 12 Page 10 Board Page 18 VolumeUniterUniter 57, Issue 18 march 20, 2003 THE T HE O FFICIAL W EEKLY S TUDENT N EWSPAPER OF THE U NIVERSITY OF W INNIPEG Quit Stalling Says Humane Society Campaign Launched Against the Use of Sow Stalls in Manitoba “Human life.” CORTNEY The European Union has banned the P ACHET prolonged use of sow stalls as of 2013. News Editor However, some countries have moved ahead of legislation. Great Britain, Sweden and The Winnipeg Humane Denmark have all banned sow stalls. Finland Society is asking will ban crates in 2006 and the Netherlands Manitobans to join in the in 2008. New Zealand pig farmers have campaign against sow stalls voted to eliminate sow stalls by 2012. and independent farmers are echoing their “This move is happening around the demands. world,” stated Burns. “We’re not the first to Vicki Burns, Executive Director of the talk about it.” Winnipeg Humane Society, believes that While Wowchuk did not disclose financial gain is the main motive in the use of whether or not the government planned to sow stalls. implement a ban, she stated that providing “I think it’s economics,” said Burns.“They information to the public about sow housing end up making more money.” is a priority. The Winnipeg Humane Society will be “We promote alternative sow housing,” looking for opportunities to set up informa- said Wowchuk. tion tables and publicly display “Penelope”, The corporate farms, many using the sow their sow, in her crate. -

Artist Title 15 Distracted 110 Rapture (Tastes So Sweet) 112 Cupid

Artist Title 15 Distracted 110 Rapture (Tastes So Sweet) 112 Cupid [Karaoke] 112 Dance With Me [Karaoke] 112 It's Over Now [Karaoke] 112 Peaches and Cream 112 U Already Know [Karaoke] 311 All Mixed Up [Karaoke] 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 311 Creatures 311 Don't Tread On Me [Karaoke] 311 First Straw 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe 702 Where My Girls At [Karaoke] .38 Special Back Where You Belong .38 Special Second Chance 10 Years Wasteland [Karaoke] 10 Years After I'd Love to Change the World 100 Proof Aged in Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping 10000 Maniacs I Like The Weather 10000 Maniacs More Than This 10000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10CC I'm Not In Love 14 Waycross Nineteen 1910 Fruitgum C Simon Says 2 Live Crew Do Wha Diddy Diddy 2 Live Crew Me So Horny 2 Live Crew We Want Some Pussy 2 Pac Changes 2 Pac Thugz Mansion [Karaoke] 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 22 Minutes Sorry (Parody) 2Pac California Love 2Pak Until the End of Time 3 Days Grace I Hate Everything About You 3 Days Grace Just Like YOu 3 Days Grace Never Too Late 3 Days Grace The Good Life 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Duck And Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Live For Today [Karaoke] 3 Doors Down Loser [Karaoke] 3 Doors Down Road I'm On 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain [Karaoke] 3 Of Hearts Christmas Shoes 3 Of Hearts Love Is Enough [Karaoke] 30 Seconds to Mars Walk on Water 30 Seconds To Mars Walk on Water