Roses and Castles: Competing Visions of Canal Heritage and the Making of Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Annual Report 2015

Britain’s Creative Greenhouse A Year of Impact and Growth Channel Four Television Corporation Report and Financial Statements 2015 Channel Four Television Corporation Report and Financial Statements 2015 Incorporating the Statement of Media Content Policy Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraph 13(1) of Schedule 3 to the Broadcasting Act 1990 annualreport.channel4.com Printed by Park Communications on FSC® certified paper. Park is an EMAS certified CarbonNeutral® company and its Environmental Management System is certified to ISO14001. 100% of the inks used are vegetable oil based, 95% of press chemicals are recycled for further use and on average 99% of any waste associated with this production will be recycled. This document is printed on Heaven 42, a paper containing 100% virgin fibre sourced from well-managed, responsible, FSC® certified forests. Some pulp used in this product is bleached using an elemental chlorine free (ECF) process and some using a totally chlorine free (TCF) process. Channel 4 Annual Report 2015 Contents 03 Chair’s statement 04 Financial report and statements Contents Chief Executive’s statement 06 Strategic report 108 2015 at a glance 10 Report of the Members 119 Independent auditor’s report 121 Statement of Media Content Policy Corporate governance 123 The remit and model 12 Members 127 Investing in innovation 16 Audit Committee report 129 Making an impact 26 Members’ remuneration report 132 Spotlights 40 Consolidated income statement Our programmes 48 and statement of comprehensive Thank you 92 income -

West Midlands Annual Report

West Midlands Annual Report 2020/21 canalrivertrust.org.uk Introduction A year in numbers Introduction from Regional Director & Regional to maintain, protect and develop the Advisory Board Chair £20m total spend West Midlands canal network in 2020/21 Delivered With a further miles Whilst Covid has dramatically changed all our lives and £2.6m £1.2m +35 – 41% 559 of externally delivered More people have used our of canals made life extremely difficult for so many, over this time, funded projects by other towpaths this year, with a 41% our canals have been discovered by many more people organisations, increase in users at Sandwell, and and £4m benefitting 35% increase at Walsall. Footfall and miles as a place for nature, exercise and wellbeing. secured for the network has also increased in Coventry 6 8 3 future years and Wolverhampton of towpaths Last October, we reached an During this time, we have Alongside the physical works, important milestone, when continued to work with our we are working closely with the Revolution Walk – along the partners across the region to Organising Committee’s Physical Birmingham Mainline Canal from make important improvements to Activity & Wellbeing programme, the centre of Birmingham to our waterways. We’ve spent over looking at leaving a legacy of £4.1m 26 900+ Chance Glassworks in Sandwell £20million on management and engagement on our waterways. priority works – received the Green Flag maintenance across the network, reservoirs access points For both the Coventry UK City of programme delivered Award. We have since submitted and we’ve worked with thousands to our canals Culture 2021 and the Birmingham Green Flag applications for the of volunteers wanting to make 2022 Commonwealth Games, Coventry Canal (from Coventry a difference to their local canal we look forward to continuing to Basin to Hawkesbury Junction), environment. -

Boaters' Update 22 April 2016 I Start This Edition By

Boaters’ Update 22 April 2016 I start this edition by unashamedly preaching to the converted. As mentioned in the last edition we work with Drifters Waterways Holidays to, once a year, run Open Days around the country. It gives those considering a waterway holiday the chance to get out on the cut for free to see if it’s for them. Of course, most readers need no such enticement! I am very pleased to report that this year over 3,000 people took the opportunity to go cruising – three times as many as did last year. And with Drifters reporting a 14% increase in bookings last year it seems that more and more people are getting the boating bug. I don’t think the rising popularity of boating can be put down to just one thing but inspirational TV series such as Great Canal Journeys certainly help. In fact, that gives me a handy segue into the first article of this edition – it’s a review, of sorts, of the book that accompanies the first series of Barging Round Britain. If you’re quick, you can read it and the rest of this edition before the second series starts tonight on ITV at 8pm. Elsewhere in this edition you’ll find: Last week, this week - what’s happening on or by the cut? Armchair cruising Mike’s monthly column – Waterway Writers Keeping your boat secure Maintenance, repair or restoration work affecting cruising this weekend Bits and bobs If there’s something you’d like to share with the boating community via this update then please drop me a line. -

Annual Report 2012

Re-Union Canal Boats Ltd Annual Report 2014 Introduction Re-Union Canal Boats is a social enterprise based on and around the Union Canal. We engage meaningfully with canalside communities in Edinburgh and Falkirk through a variety of projects including boat training, community engagement, canal clean up’s, education trips, floating youth clubs and co-ordinating and the annual Edinburgh Canal Festival and Raft Race. We provide training programmes in Edinburgh and Falkirk for people referred to us by a range of agencies and also for people who love the canal. Re-Union offer boat trips to community and private groups in Falkirk and Edinburgh to generate income. We also own 51% of Capercaillie Cruisers, a holiday hire boat company, based in Falkirk, which is the trading arm of the organisation. Board The voluntary Board of Directors of Re-Union in 2014 consisted of Sheila Durie, Sam Baumber, Douglas Tharby, Gerry Baker, Helen Wyllie, Jan Colligen, Christine Wilson, Sheila McMillan and Caroline St Johnston. Sam Baumber resigned in July 2014 due to pressure of work. The Board regretfully accepted his resignation as Sam was a co-founder of Re-Union and had put many hours into the development of the organisation. The Board thanked him for everything he had done to make the organisation into what it is today. Staff Pat Bowie continued as full-time General Manager. Sam Adderley remained as Canal Community Development Worker while Anna Canning and Miranda Morgan held the post of Volunteer Development Worker in Falkirk and Edinburgh respectively. Miranda was replaced by Jenny White in February and Lesley Young replaced Anna in August. -

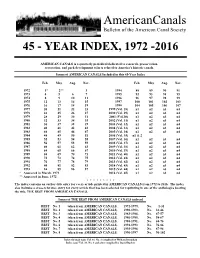

AC 45 Year Index

AmericanCanals Bulletin of the American Canal Society 45 - YEAR INDEX, 1972 -2016 AMERICAN CANALS is a quarterly periodical dedicated to research, preservation, restoration, and park development efforts related to America's historic canals. Issues of AMERICAN CANALS Included in this 45-Year Index Feb. May Aug. Nov. Feb. May Aug. Nov. 1972 1* 2** 3 1994 88 89 90 91 1973 4 5 6 7 1995 92 93 94 95 1974 8 9 10 11 1996 96 97 98 99 1975 12 13 14 15 1997 100 101 102 103 1976 16 17 18 19 1998 104 105 106 107 1977 20 21 22 23 1999 (Vol. 28) n1 n2 n3 n4 1978 24 25 26 27 2000 (Vol. 29) n1 n2 n3 n4 1979 28 29 30 31 2001 (Vol.30) n1 n2 n3 n4 1980 32 33 34 35 2002 (Vol. 31) n1 n2 n3 n4 1981 36 37 38 39 2003 (Vol. 32) n1 n2 n3 n4 1982 40 41 42 43 2004 (Vol. 33) n1 n2 n3 n4 1983 44 45 46 47 2005 (Vol. 34) n1 n2 n3 n4 1984 48 49 50 51 2006 (Vol. 35) n1 & 2 1985 52 53 54 55 2007 (Vol. 36) n1 n2 n3 n4 1986 56 57 58 59 2008 (Vol. 37) n1 n2 n3 n4 1987 60 61 62 63 2009 (Vol. 38) n1 n2 n3 n4 1988 64 65 66 67 2010 (Vol. 39) n1 n2 n3 n4 1989 68 69 70 71 2011 (Vol. 40) n1 n2 n3 n4 1990 72 73 74 75 2012 (Vol. -

Meeting of the Board of Trustees

MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Minutes of a meeting of the Board of Trustees (the Trustees) of Canal & River Trust (the Trust) held on Tuesday 22 November 2016 at 8.30am at Holiday Inn London Stratford City, 10a Chestnut Plaza, Westfield, Stratford City, London, E20 1G Present Allan Leighton, Chair Lynne Berry, Trustee and Deputy Chair Jane Cotton, Trustee John Dodwell, Trustee Frances Done, Trustee Nigel Annett, Trustee Jenny Abramsky, Trustee Janet Hogben, Trustee Tim Reeve, Trustee Ben Gordon, Trustee In attendance Richard Parry, Chief Executive Stuart Mills, Director Sandra Kelly, Director Sophie Castell, Director Heather Clarke, Director Ian Rogers, Director Julie Sharman, Director Simon Bamford, Director Gill Eastwood (minute taker) Darren Leftley, Head of Commercial Water Development 16/186 APOLOGIES No apologies were received. 16/187 CHAIR’S WELCOME AND REMARKS The Chair welcomed all attendees to the meeting. 16/188 REGISTER OF INTERESTS AND DECLARATION OF INTERESTS IN ANY MATTER ON THE AGENDA The attendees declared interests and set out in Report CRT224. redacted 16/189 MINUTES AND SCHEDULE OF ACTIONS The minutes of the following meeting were approved: • Board of Trustees, Friday 23 September 2016 Summary of actions arising from Board Meetings All matters arising were in hand or on the agenda. 16/190 redacted 16/191 redacted 16/192 redacted 16/193 redacted 16/194 redacted 16/195 redacted 16/196 redacted 16/197 GOVERNANCE REPORT GE presented paper CRT232 which drew attention to various matters of Governance. Revisions to the Scheme of Delegation were reported as having been actioned and the Fundraising Committee has been deleted. -

Graham Hodson Editor A Vid, FCP

Agent: Bhavinee Mistry [email protected] 020 7199 3852 Graham Hodson Editor Avid, FCP Education University of Nottingham. BSc Joint Honours - Physics and Applied Physics with Electronics 4 ‘A’ Levels 12 ‘O’ levels NOCN accredited qualification in Health and Safety. 6 credits at Level 2 Documentary and Factual Are Women the Fitter Sex? Blink Films Channel 4 60 min Documentary, Additional Editor Doctor Ronx, an emergency Doctor from London’s Hackney Homerton Hospital, takes us on a journey of discovery, interviewing researchers and patients, in search of answers. There have currently been over 20 million coronavirus cases around the world and Covid-19 seems to be affecting more men than women. This one-off special will solve the mystery of - are women truly the fitter sex? Royals Declassified Blink Films Channel 4 60 min Documentary, Additional Editor The three-part series looks at the Queen’s relationship with her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, and the rest of her family, as well as British and foreign politicians. The programme is based on declassified documents, including letters, diaries, eye-witness testimony and audio recordings. Wonderful World of Truckers Crackit Channel 5 60 min Factual This series a rare glimpse into the bustling world of trucking and heavy vehicle rescue. Cameras capture the entire recovery mission cycle as heavy rescue companies risk life and limb to perform extreme rescue missions and keep Britain’s roads moving. Producer/Director: Simon Withington Save Money: Lose Weight TwoFour ITV 30 min Factual Entertainment Series that reveals a wealth of money saving tips and tricks to help people to lose weight and eat well without spending a fortune Producer/Director: Gill Hennessey How Do Animals Do It? Wag TV Animal Planet 30 min Factual This series travels the world to explain the bizarre, the brilliant and the most mind blowing animal behaviours. -

Caledonian Canal Centre Fort Augustus • Acquisition £600K (Inc

Welcome Caledonian Canal Customer Forum 2017 Agenda 10:30am Welcome 10.35am Operations Overview (Scotland) by Russell Thomson, Head of Customer Operations 10.55am Overview of Caledonian Canal Customer Operations by Ailsa Andrews, Customer Operations Manager 11.15am Communications overview and Pricing Consultation by Josie Saunders, Head of Corporate Affairs 11.30am Growing a Tourism Business by Mark Smith, Head of Tourism & Destinations 11.45am Q&As followed by refreshments 12.30pm Ends Russell Thomson Head of Customer Operations Operational Overview (Scotland) Revenue split by year 70% 60% 50% 40% Own Income GIA 30% 20% 10% 0% 12-13 13-14 14-15 15-16 Total income Release of capital grant Interest 2% 0% Commercial income 22% Grant-in-aid 40% Retail income 13% Freight Income 1% Third party contributions Cost recoveries & sundry 20% sales 2% Commercial income SWD Premiums 4% Commercial Craft Licences Leisure Moorings 4% 11% Property Rents 25% Craft Licences 11% This is the split of Bigg Regeneration the 22% of Own 14% Income that is classed as Utilities Commercial 31% Income Insurance re-charges 0% Canal income & expenditure Lowlands Caledonian Crinan Craft Licences (Nav. 38,283 263,555 168,355 Licence & Short Term/Transit Mooring Fees 151,643 193,724 84,425 Commercial Income 27,117 208,970 127,396 Total Boating 217,043 666,249 380,176 Income Total Expenditure 2,845,387 2,196,064 1,051,520 Capital Spend Top 20 Assets 1 11 Ness Weir Refurbishment Crinan Canal: lock gates 2 Tomnahurich Bridge M&E 12 Upgrade Caledonian Canal: Lock grouting 3 13 Avon Aqueduct 19 Caledonian Canal Leakage Repair 4 Linlithgow Embankments 14 Crinan Canal Leakage Repair Leakage Repair 5 Muirtown Bridge M&E 15 Lowlands Canals Leakage Repair Upgrade 6 16 Ardrishaig Swing Bridge 1 - M&E TFW Site Works repairs 7 17 Kytra & Cullochy Locks, Weir Oich Weir and Reach repairs. -

Communications Update 21St August 2015

Communications Update 21 st August 2015 News Round up The emergency repairs on the Rufford branch of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal have attracted media attention last week, with BBC TV North West Tonight, BBC Radio Merseyside . BBC Radio Lancashire and the local newspapers all covering the Trust’s work Timothy West mentioned the Trust on BBC Radio Northampton as he promoted Great Canal Journeys. The series is being repeated to much media fanfare on Channel 4 starting last weekend The Sunday Telegraph is the latest national newspaper to examine the rising popularity of living afloat BBC Radio Wiltshire joined our team of junior lock keepers as they helped boats through the locks at Caen Hill Flight Last weekend saw over 5,000 people come to the canal in King’s Cross to take part in Clay Cargo , the latest event of the Trust’s Arts on the Waterways programme. ITV London (16/8/15) and London Live TV (17/8/15) broadcast from the event David Viner and Pete Dunn were interviewed on BBC Radio Bristol and BBC Radio Somerset about improvements being made to Claverton Pumping Station Stuart Moodie explained major repairs to a leak on the Montgomery Canal to BBC Radio Shropshire In social media: For the Waterfront newsletter we asked our audience ‘what’s your favourite spot on your local canal and why’? The post did particularly well reaching 3,776 people on Twitter and 6,949 people on Facebook with 168 likes, comments and shares. We promoted Great Nature Watch on our channels too. The post also did well particularly on Twitter where it reached 5,556 people with 92 retweets, post clicks and favourites.