Oral History Interview with Patti Warashina, 2005 September 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Impact Report

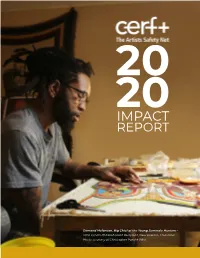

20 20 IMPACT REPORT Demond Melancon, Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters – 2020 COVID-19 Relief Grant Recipient, New Orleans, Louisiana, Photo courtesy of Christopher Porché West OUR MISSION A Letter from CERF+ Plan + Pivot + Partner CERF+’s mission is to serve artists who work in craft disciplines by providing a safety In the first two decades of the 21st century,CERF+ ’s safety net of services gradually net to support strong and sustainable careers. CERF+’s core services are education expanded to better meet artists’ needs in response to a series of unprecedented natural programs, resources on readiness, response and recovery, advocacy, network building, disasters. The tragic events of this past year — the pandemic, another spate of catastrophic and emergency relief assistance. natural disasters, as well as the societal emergency of racial injustice — have thrust us into a new era in which we have had to rethink our work. Paramount in this moment has been BOARD OF DIRECTORS expanding our definition of “emergency” and how we respond to artists in crises. Tanya Aguiñiga Don Friedlich Reed McMillan, Past Chair While we were able to sustain our longstanding relief services, we also faced new realities, which required different actions. Drawing from the lessons we learned from administering Jono Anzalone, Vice Chair John Haworth* Perry Price, Treasurer aid programs during and after major emergencies in the previous two decades, we knew Malene Barnett Cinda Holt, Chair Paul Sacaridiz that our efforts would entail both a sprint and a marathon, requiring us to plan, pivot, Barry Bergey Ande Maricich* Jaime Suárez and partner. -

On the Edge Nceca Seattle 2012 Exhibition Guide

ON THE EDGE NCECA SEATTLE 2012 EXHIBITION GUIDE There are over 190 exhibitions in the region mounted to coincide with the NCECA conference. We offer excursions, shuttles, and coordinated openings by neighborhood, where possible. Read this document on line or print it out. It is dense with information and we hope it will make your experience in Seattle fulfilling. Questions: [email protected] NCECA Shuttles and Excursions Consider booking excursions or shuttles to explore 2012 NCECA Exhibitions throughout the Seattle region. Excursions are guided and participants ride one bus with a group and leader and make many short stops. Day Dep. Ret. Time Destination/ Route Departure Point Price Time Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Tacoma Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Bellingham Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 2:00 pm 7:00 pm Bellevue & Kirkland Convention Center $59 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 12:45 pm Northwest Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 1:30 pm 6:15 pm Northeast Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 6:15 pm Northwest/Northeast Seattle Convention Center $69 combo ticket *All* excursion tickets must be purchased in advance by Tuesday, March 13. Excursions with fewer than 15 riders booked may be cancelled. If cancelled, those holding reservations will be offered their choice of a refund or transfer to another excursion. Overview of shuttles to NCECA exhibitions and CIE openings Shuttles drive planned routes stopping at individual venues or central points in gallery dense areas. -

Earthenware Clays

Arbuckle Earthenware Earthenware Clays Earthenware usually means a porous clay body maturing between cone 06 – cone 01 (1873°F ‐ 2152°F). Absorption varies generally between 5% ‐20%. Earthenware clay is usually not fired to vitrification (a hard, dense, glassy, non‐absorbent state ‐ cf. porcelain). This means pieces with crazed glaze may seep liquids. Terra sigillata applied to the foot helps decrease absorption and reduce delayed crazing. Low fire fluxes melt over a shorter range than high fire materials, and firing an earthenware body to near vitrification usually results in a dense, brittle body with poor thermal shock resistance and increased warping and dunting potential. Although it is possible to fire terra cotta in a gas kiln in oxidation, this is often difficult to control. Reduced areas may be less absorbent than the rest of the body and cause problems in glazing. Most lowfire ware is fired in electric kilns. Gail Kendall, Tureen, handbuilt Raku firing and bodies are special cases. A less dense body has better thermal shock resistance and will insulate better. Earthenware generally shrinks less than stoneware and porcelain, and as a result is often used for sculpture. See Etruscan full‐size figure sculpture and sarcophagi in terra cotta. At low temperatures, glaze may look superficial & generally lacks the depth and richness of high fire glazes. The trade‐offs are: • a brighter palette and an extended range of color. Many commercial stains burn out before cone 10 or are fugitive in reduction. • accessible technology. Small electric test kilns may be able to plug into ordinary 115 volt outlets, bigger kilns usually require 208 or 220 volt service (the type required by many air conditioners and electric dryers). -

Craft Alliance Center for Art and Design Records (S0439)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY S0439 (SA0010, SA2390, SA2492, SA2714, SA3035, SA3068, SA3103, SA3633, SA3958) CRAFT ALLIANCE CENTER FOR ART AND DESIGN RECORDS This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- St. Louis. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Introduction Approximately 58 cubic feet The Craft Alliance is a non-profit, cultural and educational organization which promotes the production, enjoyment, and understanding of the crafts. The records include budgets, bylaws, correspondence, exhibition schedules, Education Center program schedules, newsletters, scrapbooks, and photographs. Donor Information The records were donated to the University of Missouri by Mrs. Norman Morse on January 29, 1971 (Accession No. SA0010). Additions were made on April 7, 1981 by a representative of the Craft Alliance (Accession No. SA2930); November 2, 1982 by Mary Colton (Accession No. SA2492); September 11, 1985 by Wilda Swift (Accession No. SA2714); December 1, 1991 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3035); June 24, 1992 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3068); December 28, 1992 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3103); September 7, 2005 by Alexi Glynias (Accession No. SA3633); July 12, 2011 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3958); August 14, 2020 by Mark Witzling (Accession No. SA4474); August 26, 2020 by Mark Witzling (Accession No. SA4479). Copyright and Restrictions The Donor has given and assigned to the State Historical Society of Missouri all rights of copyright which the Donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the Society from others. -

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad. -

Acknowledgments from the Authors

Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, published by University of North Carolina Press. Please note that this document provides a complete list of acknowledgments by the authors. The textbook itself contains a somewhat shortened list to accommodate design and space constraints. Acknowledgments from the Authors The Craft-Camarata Frederick Hürten Rhead established a pottery in Santa Barbara in 1914 that was formally named Rhead Pottery but was known as the Pottery of the Camarata (“friends” in Italian). It was probably connected with the Gift Shop of the Craft-Camarata located in Santa Barbara at that time. Like his pottery, this book is not an individual achievement. It required the contributions of friends of the field, some personally known to the authors, but many not, who contributed time, information and funds to the cause. Our funders: Windgate Charitable Foundation / The National Endowment for the Arts / Rotasa Foundation / Edward C. Johnson Fund, Fidelity Foundation / Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund / The Greenberg Foundation / The Karma Foundation / Grainer Family Foundation / American Craft Council / Collectors of Wood Art / Friends of Fiber Art International / Society of North American Goldsmiths / The Wood Turning Center / John and Robyn Horn / Dorothy and George Saxe / Terri F. Moritz / David and Ruth Waterbury / Sue Bass, Andora Gallery / Ken and JoAnn Edwards / Dewey Garrett / and Jacques Vesery. The people at the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design in Hendersonville, N.C., administrators of the book project: Dian Magie, Executive Director / Stoney Lamar / Katie Lee / Terri Gibson / Constance Humphries. Also Kristen Watts, who managed the images, and Chuck Grench of the University of North Carolina Press. -

2011 Honor Roll

The 2011 Archie Bray p Alexander C. & Tillie S. Andrew Martin p Margaret S. Davis & Mary Roettger p Barbara & David Beumee Park Avenue Bakery Jane M Shellenbarger p Ann Brodsky & Bob Ream Greg Jahn & Nancy Halter p Denise Melton $1,000 to $4,999 Charles Hindes Matching Gift 2011 From the Center p p p p Honor Roll shows Ted Adler p Dwight Holland Speyer Foundation Mathew McConnell Bruce Ennis Janet Rosen Nicholas Bivins Alex Kraft Harlan & William Shropshire Amy Budke Janice Jakielski Melissa Mencini Organizations to the Edge: 60 Years cumulative gifts of cash, Allegra Marketing Ayumi Horie & Chris & Kate Staley p Karl McDade p Linda M. Deola, Esq, Diane Rosenmiller & Mark Boguski p Marian Kumner Kayte Simpson Lawrence Burde Erin Jensen Forrest Merrill Organizations matching of Creativity and securities & in-kind Print & Web Robin Whitlock p Richard & Penny Swanson pp Bruce R. & Judy Meadows Morrison, Motl & Sherwood Nicholas Seidner pp Fay & Phelan Bright Jay Lacouture p Gay Smith p Scott & Mary Buswell Michael Johnson Sam Miller employee gifts to the Innovation at the Autio standing casually in jeans and work shirts. The Bray has certainly evolved since 1952, a time contributions made Gary & Joan Anderson Kathryn Boeckman Howd Akio Takamori p Andrew & Keith Miller Alanna DeRocchi p Elizabeth A. Rudey p Barbara & Joe Brinig Anita, Janice & Joyce Lammert Spurgeon Hunting Group Dawn Candy Michael Jones McKean John Murdy Archie Bray Foundation Archie Bray They came from vastly different cultural and when studio opportunities for ceramic artists January 1 through Target Jeffry Mitchell p Mary Jane Edwards Renee Brown p Marjorie Levy & Larry Lancaster Abigail St. -

HONOR ROLL & NEWSLETTER Spring 2018

archiebrayfoundation HONOR ROLL & NEWSLETTER Spring 2018 MOVED IN AND MAKING POTS 2017 BRAY COMMUNITY NewEducationandResearchFacility The “Bray community” comprises many—residents, students, community artists, volunteers, donors and more. And what brings them all together is simple… a passion for a place and people committed to the enrichment of the ceramic arts. To everyone who lends their enthusiasm, generosity and energy: Thank You. 250 190 Friends of the Bray Individuals and and Members Business Supporters Education and Research Facility 241 61 The doors are open and there’s clay on the floor! Following a ribbon-cutting ceremony Artists Volunteers and celebratory banquet, we opened the Bray’s new Education and Research Facility with its first session of classes in October 2017. Now in the middle of our third session of classes in the building, artists and students have more opportunities to explore their creativity in a greater diversity of class offerings than ever before. 11,300 911 Facebook Students Friends Not only are class instruction and open studio time able to happen concurrently thanks to two, large flexible classrooms, 2,641 20,000 Twitter Instagram but new glazing and plaster labs and Followers Followers auxiliary spaces make it possible for the resident-artist instructors to explore their specializations and interests in special-topics courses like mold-making IN MEMORIAM and advanced anatomical studies for In 2017 and early 2018, we were saddened to lose sculpting. Moreover, the building includes some dedicated members of the Bray community. a new home for the Bray’s Library, making Gordon Bennett, Local Supporter this extensive collection of ceramics- Jim Cassidy, Local Supporter based titles available for research, reference and inspiration. -

Semi-Annual Sale: up to 60% Off

ADVERTISEMENT Semi-Annual Sale: Up to 60% Off ENTERTAINMENT & ARTS Ceramic art, once written off as mere craft, wins a brighter spotlight in the L.A. scene Visitors to the recent Scripps College Ceramic Annual consider “The Guardian,” a 2015 piece of stoneware, underglaze, glaze, resin and milk paint by Kyungmin Park. The longtime event is now joined by two new ceramics biennials, signaling a resurgence for the medium. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) By LEAH OLLMAN APRIL 25, 2018 | 2:44 PM f anything is a sign of the elevated status of ceramics, it's the central place a kiln now occupies on the campus of CalArts. I Once in disrepair because of limited interest, the kiln is in high demand. The studio area for ceramics, once a neglected corner, has become "something of a social hub," reports Thomas Lawson, dean of the School of Art. "Ceramics has flourished at CalArts in sync with its resurgence all over." Painting has been pronounced dead enough times to render the claim meaningless, if not ludicrous. But has clay, that most primordial matter, ever been significant enough as an art medium to merit killing off? In the last decade, however, the spotlight has burned klieg-bright and kiln-hot, to the point where clay's standing in the wider art world has never been higher, the L.A. scene never more alive. Two museums have just launched ceramic biennials, complementing the Scripps College Ceramic Annual, the longest continuously running show of its kind in the country, which recently finished in its 74th iteration. -

CLAYWORKS: 20 AMERICANS Museum of Contemporary Crafts of the American Crafts Council June 18-September 12, 1971

CLAYWORKS: 20AMERICANS CLAYWORKS: 20 AMERICANS Museum of Contemporary Crafts of The American Crafts Council June 18-September 12, 1971 Raymond Allen Maps Robert Arneson The Cook Clayton Bailey Creatures Patti Warashina Bauer layered Drea ms Jack Earl Penguins Kurt Fishback Houses Verne Funk Mouth Pots David Gilhooly Animals Dick Hay Traps Rodger Lang Pies Marilyn Levine Garments William Lombardo Washington Cows James Melchert A's Richard Shaw Sinking Ships Victor Spinski Machines Bill Stewart Duck Houses & Snak~s Chris Unterseher Bookends Peter VandenBerge Vegetables Ken neth Vavrek Bullets William Warehall Cakes ) 20 Americans (from left 10 righI, lop 10 bottom) Rodger Lang David Gilhooly Clayton Bailey Robert Arneson Verne Funk Victor Spinski Dick Hay Raymond Allen William Warehall Jack Earl Richard Shaw Bill Stewart Chris Unterseher Peter Vanden Berge James Melchert Patti Warashina Bauer William Lombardo Kurt E. Fishback Kenneth Vavrek Marilyn Levine Acknowledgements We wish to express our appreciation to the artists for making their work avail able and to the galleries and collectors who loaned pieces for the exhibition: Mr. and Mrs. Wayne Andersen; Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Nones; Obelisk Gallery, Inc.; State University College, Potsdam, New York; Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Stevenson; Ann Stockton and Peter Voulkos; and Allan Stone. Introduction Clayworks: 20 Americans represents Arneson and James Melchert must a group of ceramic artists with a certainly be mentioned among the very sensitive view of the world, artists who were instrumental who are engaged in making objects, in defining the object-oriented usually in a series, to develop a ceramic movement in the early particular theme with social, sixties. -

The Juliette K

The Juliette K. and Leonard S. Rakow Research Library The Corning Museum of Glass Finding Aid for the ARTIST FILES, ARTIST INTERVIEWS & ADDITIONAL INFORMATION COMPILED BY KAREN CHAMBERS (bulk 1975–2000) ACCESS: Open for research BIBLIOGRAPHIC #: 59848 COPYRIGHT: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be discussed with one of the following: the Archivist, Librarian, or the Rights & Reproductions Manager. PROCESSED BY: Nive Chatterjee, May 2007 PROVENANCE: Karen Chambers donated this archive in 1999 SIZE: 14 linear feet (15 boxes) The Juliette K. and Leonard S. Rakow Research Library The Corning Museum of Glass 5 Museum Way Corning, New York 14830 Tel: (607) 974-8649 TABLE OF CONTENTS Karen Chambers 3 Scope and Content Note 4 Series Descriptions 5-6 Box and Folder List 7-24 Series I: Artist Files 7-18 Sub-Series A: Artist Files (slides) Sub-Series B: Artist Files (non-slides) Sub-Series C: Artist Interviews Series II: Articles, Notes, Report & Slides 18-21 Sub-Series A: Slides Sub-Series B: Glass in Different Countries Sub-Series C: Articles, Notes & Report Sub-Series D: Miscellaneous Series III: Audio Cassettes 21-24 Sub-Series A: Audio Cassettes Sub-Series B: Audio Microcassettes 2 KAREN CHAMBERS Karen Chambers received her B.F.A. from Wittenberg University, Springfield, OH, and her M.A. in art history from the University of Cincinnati. From 1983 to 1986, Karen Chambers was editor of New Work, now Glass: The UrbanGlass Quarterly, published by UrbanGlass. She has written over a hundred articles on glass for magazines including: Neues Glas, Art & Antiques, The World & I, and American Craft. -

Patti Warashina (1940 - )

PATTI WARASHINA (1940 - ) Patti Warashina, along with Robert Sperry and Howard Kottler were instrumental in bringing the Seattle ceramic scene to prominence, heading up the department at the University of Washington, Seattle, as well as producing pieces that took inspiration from the Funk movement in the Bay area but with their own interpretations. Warashina is best known for her figurative sculpture – pieces that tell stories which are often dream- like or fantasies – and ranging in size from very small to larger-than-life. She works in low-fire polychrome ceramics, the colors and surface decoration both vivid and animated. While her primarily female figures clearly emerge from her own experiences, Warashina says, “They aren’t me exactly, or any version of me….they represent what I know and what I’m curious about. When I’m curious about something else, I’ll move on.”1 1. Hackett, Regina. “Pioneering Ceramic Artist Patti Warashina is Still Standing.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 18, 2001. http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/visualart/50966_pattiwarashina18.shtml ARTIST’S STATEMENT – PATTI WARASHINA “The human figure has been an absorbing visual fascination in my work. I use the figure in voyeuristic situations in which irony, humor, absurdities portray human behavior as a relief from society’s pressure and frustrations on mankind. At times, I use the figure in complex arrangements so that it will be seethingly alive. I like the visual stimulation of portraying human energy, as a way to compare it to any biological organization found