Journalists and Terrorism: Captives of the Libertarian Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

83Rd National Headliner Awards Winners

83rd National Headliner Awards winners The 83rd National Headliner Award winners were announced today honoring the best journalism in newspapers, photography, radio, television and online. The awards were founded in 1934 by the Press Club of Atlantic City. The annual contest is one of the oldest and largest in the country that recognizes journalistic merit in the communications industry. Here is a list of this year's winners beginning with the Best of Show in each category: Best of show: Newspapers “Painkiller Profiteers” Eric Eyre Charleston Gazette-Mail, Charleston, W. Va. Best of show: Photography “An Assassination” Burhan Ozbilici Associated Press, New York, N.Y. Best of show: Online The Panama Papers, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a project of the Center for Public Integrity Best of show: Radio “Texas Standard: Out of the Blue: 50 Years After the UT Tower Shooting” Texas Standard staff Texas Standard, Austin, Texas Best of show: TV First place “Cosecha de Miseria (Harvest of Misery) & The Source” Staff of weather.com and Telemundo Network weather.com and Telemundo Network, New York, N.Y. DAILY NEWSPAPERS AND NEWS SYNDICATES Spot News in daily newspapers, all sizes First Place “Dallas Police Shootings” The Dallas Morning News Staff Dallas, Texas Second Place “Oakland's Ghost Ship warehouse fire” East Bay Times staff East Bay Times, San Jose, California Third Place “The Shooting Death of Philando Castile” Star Tribune staff Star Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota Local news beat coverage or continuing story by an individual or team First Place “The Pulse Shooting” Orlando Sentinel staff Orlando Sentinel, Orlando, Fla. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Philip Matthew Stinson, Sr. 232

CURRICULUM VITAE PHILIP MATTHEW STINSON, SR. 232 Health & Human Services Building Criminal Justice Program Department of Human Services College of Health & Human Services Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, Ohio 43403-0147 419-372-0373 [email protected] I. Academic Degrees Ph.D., 2009 Department of Criminology College of Health & Human Services Indiana University of Pennsylvania Indiana, PA Dissertation Title: Police Crime: A Newsmaking Criminology Study of Sworn Law Enforcement Officers Arrested, 2005-2007 Dissertation Chair: Daniel Lee, Ph.D. M.S., 2005 Department of Criminal Justice College of Business and Public Affairs West Chester University of Pennsylvania West Chester, PA Thesis Title: Determining the Prevalence of Mental Health Needs in the Juvenile Justice System at Intake: A MAYSI-2 Comparison of Non- Detained and Detained Youth Thesis Chair: Brian F. O'Neill, Ph.D. J.D., 1992 David A. Clarke School of Law University of the District of Columbia Washington, DC B.S., 1986 Department of Public & International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences George Mason University Fairfax, VA A.A.S., 1984 Administration of Justice Program Northern Virginia Community College Annandale, VA 1 II. Academic Positions Professor, 2019-present (tenured) Associate Professor, 2015-2019 (tenured) Assistant Professor, 2009-2015 (tenure track) Criminal Justice Program, Department of Human Services Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 (non-tenure track) Department of Criminology Indiana University of -

Station ID Time Zone Long Name FCC Code 10021 Eastern D.S. AMC AMC 10035 Eastern D.S

Furnace IPTV Media System: EPG Support For Furnace customers who are subscribed to a Haivision support program, Haivision provides Electronic Program Guide (EPG) services for the following channels. If you need additional EPG channel support, please contact [email protected]. Station ID Time Zone Long Name FCC Code Station ID Time Zone Long Name FCC Code 10021 Eastern D.S. AMC AMC 10035 Eastern D.S. A & E Network AETV 10051 Eastern D.S. BET BET 10057 Eastern D.S. Bravo BRAVO 10084 Eastern D.S. CBC CBC 10093 Eastern D.S. ABC Family ABCF 10138 Eastern D.S. Country Music Television CMTV 10139 Eastern D.S. CNBC CNBC 10142 Eastern D.S. Cable News Network CNN 10145 Eastern D.S. HLN (Formerly Headline News) HLN 10146 Eastern D.S. CNN International CNNI 10149 Eastern D.S. Comedy Central COMEDY 10153 Eastern D.S. truTV TRUTV 10161 Eastern D.S. CSPAN CSPAN 10162 Eastern D.S. CSPAN2 CSPAN2 10171 Eastern D.S. Disney Channel DISN 10178 Eastern D.S. Encore ENCORE 10179 Eastern D.S. ESPN ESPN 10183 Eastern D.S. Eternal Word Television Network EWTN 10188 Eastern D.S. FamilyNet FAMNET 10222 Eastern D.S. Galavision Cable Network GALA 10240 Eastern D.S. HBO HBO 10243 Eastern D.S. HBO Signature HBOSIG 10244 Pacific D.S. HBO (Pacific) HBOP 10262 Central D.S. Fox Sports Southwest (Main Feed) FSS 10269 Eastern D.S. Home Shopping Network HSN 10309 Pacific D.S. KABC ABC7 KABC 10317 Pacific D.S. KINC KINC 10328 Central D.S. KARE KARE 10330 Central D.S. -

WTHR-DT 7Th 36Dbu

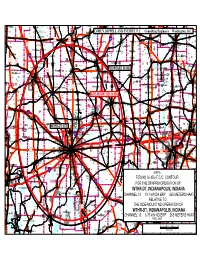

BROOK BUFFALO MONON RO 27 YAL CENTER DENVER HUNTINGTON OSSIAN ÙÚ Fairgrounds VAN WERT 30 Big Monon Trailer ÙÚ Park LAGROCOHEN, DIPPELL AND EVERIST, P.C. Consulting EngineersDELPHOS Washington, D.C. MEXICO MARKLE 224 DECATUR BEAVERDAM NTLAND WABASH ÙÚ REMINGTON NORWAY WREN M 24 24F VENEDOCIA ELIDA ONTICELLO ÙÚ LOGANSPORT Ú PERU 69 OHIO CITY A Ù ÍÌÎ LAFAYETTE AD 231 D MOUNT ETNA BLUFFTON MONROE WILLSHIRE ELGIN LIMA ARL PARK ÙÚ ittman Airport Mississinewa Reservoir ONWARD Landing SPENCERVILLE Lima Allen County Airport C YEOM VERA CRUZ HALMERS AN LA FONTAINE WARREN ROCKFORD MCGUFFEY GRISSOM AFB FORT SHAWNEE FOWLER PONETO BERNE 65 CRIDERSVILLE ÍÌÎBRO CAMDEN OKSTON VAN BUREN 41 DE ÙÚ 52 LPHI 127 ÙÚ GALVESTON CONVERSE GENEVA ÙÚ WAYNESFIELD B Delphi Muni Airport FLORA WAPAKONETA OSWELL OXFORD MARION MONTPELIER CELINA 33 Kokomo M ST. MARYS BATTLE GROUN uni Airport BRYANT ÙÚ OTTERBEIN D 421 SWAYZEE 75 BURLINGT GAS CITY PROPOSED 36 dBu BELLE CENT PINE VI ÙÚ ON GREENT PENNVILLE NEW KNOXVILLEÍÌÎ LLAGE WEST LA KOKOMO OWN COLDWATER FAYETTE UPLAND Hoover Park RUSSELLS POINTRUSHS ROSSVILL E INDIAN HEIGHTS PORTLAND NEW BREMEN JACKSON CENTER LAFAYETTE FAIRMOUNT ST. HENRY Cherokee Hills Golf MATTHEWS MINSTER ANNA W SHADELAND SALAMONIA ARREN MULBERRY WINDFALL CITY DUNKIRK 31 BURKET BELLEFONTAI MICHIGANTOWN ÙÚ SUMMITVILLE EATON TSVILLE FORT LORAMIE ATTICA PORT JEFFERSON Robert Pl NORTH STAR VAL aza FRANKF KEMPTON ALBANY ORT TIPTON RIDGEVILLE QUINCY s Ceme ELWOOD ROSSBURG SIDNEY tery CLARKS HILL SIDE-MOUNTALEXANDRIA ND 36 dBu Jackson Township Cemetery WEST LIBER NEWTOWN SARATOGA Sidney Muni Airport LIN ATLANTA FRANKTON DEN COLFAX KIRKLIN ANSONIA VERSAILLES WINGATE UNION CITY LOCKINGTON 136 ARCADIA MUNCIE 68 ÙÚ W Kiser Lake State Park ÙÚ MADISON INCHESTER Stillwater Beach Campground VEEDERSBURG THORNTOWN SHERIDAN PIQUA CICERO FLETCHER ÍÌÎ74 ST. -

WTHR-TV/WALV-CD, Indianapolis, Indiana EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021

Page: 1/6 WTHR-TV/WALV-CD, Indianapolis, Indiana EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Producer - 8722 1-3, 6-7, 9-11, 13-16, 18-19, 21-24 7 Producer - 9380 1-3, 5-16, 18-19, 21-24 12 Weekend Anchor/Reporter - 9381 1-4, 6-7, 9-11, 13-19, 21-24 7 Digital Desk Editor - 9815 1-3, 6, 9-11, 13-16, 18-24 21 Sales Project Manager- 9843 1-3, 6, 9-11, 13-19, 21-24 17 Page: 2/6 WTHR-TV/WALV-CD, Indianapolis, Indiana EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period Ball State University - Career Center 2000 W University Lucina Hall 220 Muncie, Indiana 47306 1 Phone : 765-285-2431 Y 0 Email : [email protected] Jennifer Randall Career Builder 200 N. LaSalle St Suite 1100 Chicago, Illinois 60601 2 Phone : 773-527-3600 N 0 Career Services Manual Posting Career Consultants - Oi Partners, Inc. 32 E Washington St Ste 900 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 3 Phone : 317-264-4178 Y 0 Email : [email protected] Patty Prosser 4 Current Employee - Transfer/Promotion N 1 5 Current Intern N 1 DePauw University - Hubbard Center for Student Engagement 408 South Locust St 6 Greencastle, Indiana 46135 Y 0 Phone : 765-658-4138 Email : [email protected] Erin Duffy 7 Employee Referral N 6 8 Facebook post N 1 Fort Wayne Urban League, Inc. -

San Francisco, WUSA-TV Washington and WAGA-TV Atlanta

San Francisco, WUSA-TV Washington Sandy Newton has been named enter- Palladium/New Century Television's and WAGA-TV Atlanta. tainment reporter. Power Pack film package has been li- censed to 31 stations since its release in Samuel Goldwyn Television has sold Coral Pictures has sold five telenove- mid-January. Among the stations are November Gold 2, package of "acven- las to the Univision Network: Prima- WTAF-TV Philadelphia, KGMC-TV ture" films, to more than 20 markets. vera (200 hours), to debut June 1; Cris- Oklahoma City, WXXA-TV Albany, Among the stations are WTAF-TV tal (246 hours); La Dama De Rosa (219 WAWS-TV Jacksonville and KING- Philadelphia, KTVT-TV Dallas, hours); Leonela (133 hours); and Topa- TV Seattle. WDCA-TV Washington, WUAB-TV ciao (187 hours). Also, Coral recently Cleveland, KHTV(TV) Houston, concluded 111 sales in Latin America LBS Communications will distribute WGNX-TV Atlanta, KTZZ-TV Seat- on 10 novelas, including 47 deals in the one-hour HBO Sports production tle, KPLR-TV St. Louis, WVTV(TV) South America, 47 in Central America of Countdown to Tyson-Spinks, to air Milwaukee and WZTV(TV) Nashville. and nine in the Dominican Republic, between June 13 and June 26. The one- Titles include A Prayer for the Dying, four in Mexico and four in Puerto Rico. hour show is being offered via barter, Hello Mary Lou, Prom Night II and All told, Coral is now distributing 5,176 with stations getting eight minutes, April Morning. hours of Spanish-language program- and national five. Stations have option ming. -

WALV-CD Engineering Statement.Pdf

EXHIBIT E ENGINEERING STATEMENT RE IN SUPPORT OF CONSTRUCTION PERMIT FOR REPACKED FACILITIES PURSUANT TO DA 17-314 WALV-CA, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA CHANNEL 17 8.18 KW ND ERP 269.8 METERS HAAT JULY 2017 COHEN, DIPPELL AND EVERIST, P.C. CONSULTING ENGINEERS RADIO AND TELEVISION WASHINGTON, D.C. Cohen, Dippell and Everist, P.C. WALV-CA, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA PAGE 1 This engineering statement has been prepared in support of a construction permit for repacked facilities for Channel 17 pursuant to DA 17-314 on behalf of VideOhio, Inc., licensee of Class A TV station WALV-CD, licensed to Indianapolis, Indiana. WALV-CA presently is licensed to operate on television Channel 46 with a maximum visual effective radiated power (“ERP”) of 15 kW non-directional with an antenna radiation center above mean sea level (“RCAMSL”) of 521.8 meters and a height above average terrain (“HAAT”) of 269.8 meters. WALV-CA will provide its viewers appropriate advance notice of its plans to cease operations on Channel 46 prior to the transition, and will cease operating on Channel 46. Transmitter Site The existing WALV transmitter site is located at Ditch Road and 96th Street, Hamilton County, Indiana. The existing tower (Exhibit E-1) has a total overall structure height above ground of 316.8 meters (1039.4 feet). The WALV-CD antenna will be side-mounted on this tower at 270.7 meters above ground level. The registration number for the existing tower is 1024109. The geographic coordinates of the existing site are as follows: North Latitude: 39° 55' 43" West Longitude: 86° 10' 55" NAD-27 Cohen, Dippell and Everist, P.C. -

OHV Deaths Report

# Decedent Name News Source Reporter News Headline Hyperlink 1 Williquette Green Bay Press Gazette.com Kent Tumpus Oconto man dies in ATV crash Jan. 22 https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/oconto-county/2021/02/02/oconto-county-sheriff-man-dies-atv-accident/4340507001/ 2 Woolverton Idaho News.com News Staff 23-yr-old man killed in UTV crash in northern Idaho https://idahonews.com/news/local/23-year-old-man-killed-in-atv-crash-in-northern-idaho 3 Townsend KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 4 Vazquez KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 5 Taylor The Ada News.com News Staff Stonewall woman killed in UTV accident https://www.theadanews.com/news/local_news/stonewall-woman-killed-in-utv-accident/article_06c3c5ab-f8f6-5f2d-bf78-40d8e9dd4b9b.html 6 Unknown The Southern.com Marily Halstead Body of 39-yr-old man recovered from Ohio River https://thesouthern.com/news/local/body-of-39-year-old-man-recovered-from-ohio-river-after-atv-entered-water-saturday/article_612d6d00-b8ac-5bdc-8089-09f20493aea9.html 7 Hemmersbach LaCrosse Tribune.com News Staff Rural Hillsboro man dies in ATV crash https://lacrossetribune.com/community/vernonbroadcaster/news/update-rural-hillsboro-man-dies-in-atv-crash/article_3f9651b1-28de-5e50-9d98-e8cf73b44280.html 8 Hathaway Wood TV.com News Staff Man killed in UTV crash in Branch County https://www.woodtv.com/news/southwest-michigan/man-killed-in-utv-crash-in-branch-county/ -

CH PROGRAMMING 2 WFYI, PBS, Ch.20, Indianapolis 3 WHMB, Ch.40

CH PROGRAMMING CH PROGRAMMING CH PROGRAMMING 2 WFYI, PBS, Ch.20, Indianapolis 24 USA Network 341 VICELAND 3 WHMB, Ch.40, Indianapolis 25 TBS Superstation, Atlanta 342 BBC AMERICAS 4 WTTV, CBS, Indianapolis 26 WGN America 352 BET HERS 5 Local Access 27 Spike TV 372 LIFETIME MOVIES 6 WRTV, ABC, Ch. 6, Indianapolis 28 Country Music Television 404 DISNEY XD 7 THE CW 29 Disney Channel 441 ESPN NEWS 8 WISH-TV 30 The History Channel 445 GOLF CHANNEL 9 WCLJ, TBN, Ch 42,Bloomington 31 TNT 453 FXX 10 WNDY-TV, Ch.23, Marion 32 TLC 457 FOX SPORTS 1 11 WXIN, FOX, Ch.59, Indianapolis 33 Arts & Entertainment 458 DISCOVERY LIFE 12 QVC 34 Cartoon Network 490 FX MOVIE 13 WTHR NBC 35 The Weather Channel 491 INDEPENDENT FILM 36 Nickelodeon 600 CINEMAX 4.1 WTTV – HD, CBS, Indianapolis 37 HGTV 4.2 In dependent 38 Comedy Central 602 MORE MAX 604 ACTION MAX 4.3 Comet TV 39 Lifetime Television 6.1 WRTV – HD, ABC Ch. 6, Indy 40 The Discovery Channel 605 THRILLER MAX 6.2 GRIT 41 Animal Planet 6.3 Laff TV 42 Hallmark Channel 610 STARZ ENCORE 612 STARZ ENCORE ACTION 6.4 Escape TV 43 Hallmark Movie & Mysteries 8.1 W ISH – TV HD 44 FX 614 STARZ ENCORE CLASSIC 616 STARZ ENCORE SUSPENSE 8.2 Get TV 46 C-Span 8.3 Justice Network 47 Fox News 618 STARZ ENCORE BLACK 620 STARZ ENCORE WESTERNS 59.1 WXIN – HD, FOX, Ch. 59, Indy 48 Tru TV 59.2 Ant. Tv 49 Food Network 622 STARZ ENCORE FAMILY 59.3 This TV 51 The Travel Channel 630 HBO 13.1 WTHR NBC HD 52 WIPX, ION, Ch. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 6, 2021 TEGNA Honored with 86

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 6, 2021 TEGNA Honored with 86 Regional Edward R. Murrow Awards, Including Six for Excellence in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Tysons, VA – TEGNA Inc. (NYSE: TGNA) today announced its stations received 86 Regional Edward R. Murrow Awards – more than any other local broadcast television group – for excellence in broadcast journalism, including the coveted prizes for overall excellence, excellence in innovation, and the new category of excellence in diversity, equity, and inclusion. More than a third of TEGNA’s 64 stations were among the winners with four stations – KARE, KING, WFAA and WUSA – garnering overall excellence, the highest honor awarded. Seven TEGNA stations – KGW, KUSA, KSDK, NEWS CENTER Maine, WFAA and WGRZ – also won for excellence in innovation, which recognizes “news organizations that innovate their product to enhance the quality of journalism and the audience’s understanding of news.” In addition, six TEGNA stations – KARE, KGW, KSDK, WFAA, WWL and WXIA – received the Edward R. Murrow’s newest honor – excellence in diversity, equity, and inclusion – which is given for “outstanding advocacy journalism tackling the topic of diversity, racial injustice and/or inequality.” “TEGNA’s commitment to exceptional journalism has once again been recognized by the prestigious Regional Edward R. Murrow awards,” said Dave Lougee, president and CEO, TEGNA. “As our nation continues to confront acts of racial and social injustice, we are especially proud that our stations are recognized for covering and facilitating important discussions about race and inequality that will help drive systemic change.” Overall, 24 TEGNA stations were honored, with 10 awarded to KARE; nine to KUSA; eight to WFAA; seven to KDSK; six to KING and WXIA; four to KGW, NEWS CENTER Maine and WHAS; three to WBIR, WGRZ, WUSA, WTHR and WWL; two to KHOU, KXTV, WOI and WTC; and one each to First Coast News, KPNX, KTVB, KWES, WTOL and WVEC. -

Comscore Signs Local TV Ratings Contract with Dispatch Printing Company

July 7, 2016 comScore signs Local TV Ratings Contract with Dispatch Printing Company Every Local Station in Columbus, Ohio and Over Half of the Local Stations in Indianapolis, Indiana Now Subscribe to comScore's Local Television Ratings RESTON, Va., July 7, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- comScore (NASDAQ: SCOR) today announced it has signed a local TV measurement agreement with the Dispatch Printing Company television stations, WTHR-TV (NBC) in Indianapolis, Indiana and WBNS-TV (CBS) in Columbus, Ohio. The Dispatch Printing Company, a family owned local broadcast group since 1929, makes Columbus the latest market to have every major affiliate now using comScore local ratings. Both stations will now have access to comScore local advanced demographic ratings and advanced automotive ratings. "We have been watching comScore, formerly Rentrak, local television measurement make progress in our markets and across the country for several years," said CEO & Vice Chairman, Dispatch Printing Company, Michael J. Fiorile. "The timing is right in adopting comScore's local television service, which provides our markets another choice in local media measurement. The automotive advanced demographics tool will allow our stations to be better equipped to offer solutions to our advertiser partners." "We are excited to have the Dispatch Printing Company join the comScore family and are committed to providing the most reliable and powerful measurement available," said comScore's Executive Vice Chairman & President Bill Livek. "Their commitment further illustrates that the local TV industry is adopting comScore as their massive database currency." About comScore comScore, Inc. (NASDAQ: SCOR) is a leading cross-platform measurement company that precisely measures audiences, brands and consumer behavior everywhere. -

History Newsletter Summer 2018

History Newsletter Summer 2018 Edited by Norma Hiebert-Duffy What to watch out for this semester: History Programme Special Guest Lectures Autumn 2018 Friday 5 October, 12-1 in W3 Professor Máire Cross (Newcastle University) Blazing A Trail For Gender Equality: Flora Tristan (1803‑1844), Utopian Socialist and Feminist and Her Modern Influence Professor Cross is Emerita Professor of French Studies at Newcastle University and a former President both of the Society for the Study of French History and of the Association for the Study of Modern and Contemporary France. A specialist in the history of gender, the history of political ideas and the history of letter-writing, she is the world’s leading expert on Flora Tristan. Professor Cross is currently writing In the Footsteps of Flora Tristan. A Political Biography in Motion, which examines the intertwined lives of Flora Tristan and her biographer Jules-Louis Puech, an early twentieth century pacifist, feminist and socialist. Compulsory for students on HIS2033 Introduction to Contemporary History, this will also be of interest to students taking HIS1012 Interpreting European History: the Nineteenth Century. In association with Edge Hill's Gender and Sexuality Research Group. All welcome. Tuesday 20 November, 4-6 in CE102 Richard Hall (Cambridge University) Fathers' and Sons' Educational Experiences in Britain Richard Hall is completing a PhD in the Faculty of History at Cambridge University on The Emotional Lives and Legacies of Fathers and Sons in Britain, 1945-1974. Richard has published on working men’s clubs in post-war Britain, and emotions and subjectivity in oral history interviews.