What Property Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rehabilitating Repugnancy? Preserving That Piece of Medieval Lumber

REHABILITATING REPUGNANCY? PRESERVING THAT PIECE OF MEDIEVAL LUMBER SCOTT GRATTAN* This article examines restraints on alienation imposed by the grantor as a condition in the transfer of property to the grantee (rather than contractual restraints subsequently entered into by an owner). It considers whether the doctrine of repugnancy has any useful part to play in testing the validity of such restraints in light of Glanville Williams’ criticism of the doctrine as ‘pseudo-logical’ and lacking utility. Examining the numerus clausus principle and Australian, English and (certain) American cases in which the doctrine has been addressed, the article argues that a wholesale rejection of repugnancy is unwarranted. First, some version of the repugnancy doctrine is necessarily required as part and parcel of distinguishing between various forms of proprietary (and non- proprietary) interests. Second, the courts continue to apply the repugnancy doctrine in distinguishing between determinable interests and those defeasible by condition subs- equent when ascertaining the validity of a condition that operates upon a purported alienation or bankruptcy. Finally, it may be seen that testing restraints by reasonableness and policy alone, without recourse to repugnancy, can produce problematic results. The doctrine of repugnancy cannot, therefore, simply be dismissed as a mere historical relic. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 922 II The Context: Restraints -

A Bundle of Rights

A BUNDLE OF RIGHTS 17 U.S.C. § 106 (2004) Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following: (1) to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords; (2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work; (3) to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending; (4) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly; (5) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; and (6) in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission. __________ A. THE DISTRIBUTION RIGHT 17 U.S.C. § 109 (2004) (a) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106 (3), the owner of a particular copy or phonorecord lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy or phonorecord. Notwithstanding the preceding sentence, copies or phonorecords of works subject to restored copyright under section 104A that are manufactured before the date of restoration -

A Bundle of Confusion for the Income Tax: What It Means to Own Something Stephanie H

University of Cincinnati College of Law University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications Faculty Articles and Other Publications College of Law Faculty Scholarship 2014 A Bundle of Confusion for the Income Tax: What It Means to Own Something Stephanie H. McMahon University of Cincinnati College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Taxation-Federal Commons Recommended Citation Stephanie Hunter McMahon, A Bundle of Confusion for the Income Tax: What It Means to Own Something, 108 Nw. U. L. Rev. 959 (2014) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law Faculty Scholarship at University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles and Other Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 2014 by Stephanie Hunter McMahon Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 108, No. 3 A BUNDLE OF CONFUSION FOR THE INCOME TAX: WHAT IT MEANS TO OWN SOMETHING Stephanie Hunter McMahon ABSTRACT-Conceptions of property exist on a spectrum between the Blackstonian absolute dominion over an object to a bundle of rights and obligations that recognizes, if not encourages, the splitting of property interests among different people. The development of the bundle of rights conception of property occurred in roughly the same era as the enactment of the modem federal income tax. -

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water

Florida State University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1975 The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water Glenn J. MacGrady Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Glenn J. MacGrady, The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511 (1975) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 3 FALL 1975 NUMBER 4 THE NAVIGABILITY CONCEPT IN THE CIVIL AND COMMON LAW: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT, CURRENT IMPORTANCE, AND SOME DOCTRINES THAT DON'T HOLD WATER GLENN J. MACGRADY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ---------------------------- . ...... ..... ......... 513 II. ROMAN LAW AND THE CIVIL LAW . ........... 515 A. Pre-Roman Legal Conceptions 515 B. Roman Law . .... .. ... 517 1. Rivers ------------------- 519 a. "Public" v. "Private" Rivers --- 519 b. Ownership of a River and Its Submerged Bed..--- 522 c. N avigable R ivers ..........................................- 528 2. Ownership of the Foreshore 530 C. Civil Law Countries: Spain and France--------- ------------- 534 1. Spanish Law----------- 536 2. French Law ----------------------------------------------------------------542 III. ENGLISH COMMON LAw ANTECEDENTS OF AMERICAN DOCTRINE -- --------------- 545 A. -

The Principles of Gift Law and the Regulation of Organ Donation Alexandra K

Transplant International ISSN 0934-0874 REVIEW The principles of gift law and the regulation of organ donation Alexandra K. Glazier New England Organ Bank, Boston University School of Law, Waltham, MA, USA Keywords Summary allocation, consent, donation, ethics, legal, regulation. The principles of gift law establish a consistent international legal understand- ing of consent to donation under a range of regulatory systems. Gift law as Correspondence the primary legal principle is important to both the foundation of systems that Alexandra K. Glazier JD, MPH, Vice President prevent organ sales and the consideration of strategies to increase organ dona- & General Counsel, New England Organ tion for transplantation. Bank, Adjunct Professor, Boston University School of Law, 60 First Ave, Waltham, MA 02451, USA. Tel.: 617-244-8000; fax: 617- 558-1094; e-mail: alexandra_glazier@ neob.org Conflicts of Interest The authors have declared no conflicts of interest. Received: 13 September 2010 Revision requested: 13 October 2010 Accepted: 1 January 2011 Published online: 29 January 2011 doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01226.x Introduction The principles of gift law The regulation of consent to organ donation provides the Gift law has its origins in the legal doctrine of property. cornerstone to any system of transplantation by establish- To ‘‘give’’ is understood to mean ‘‘the act by which the ing the legal and ethical infrastructure from which the owner of a thing voluntarily transfers the title and posses- rights and duties of donors, transplant professionals and sion of the same from himself to another person without recipients can be understood. The approach to the con- consideration’’ [1]. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

ANNALES Inheritance and Gift Tax in Poland

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS MARIAE CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA LUBLIN — POLONIA VOL. XLV SECTIO G 1998 Zakład Prawa Finansowego ANTONI HANUSZ Inheritance and gift tax in Poland Podatek od spadków i darowizn w Polsce I Inheritance tax has been around for a very long time - already in ancient times, it was one of the fiscal measures used. From time imme morial, it has been held that the moment of handing down a legacy after the death of an owner is, because of the increase in the assets of the heir, a suitable opportunity to impose a special tax upon him. The economic character of inheritance and gift tax assigns it to the category of property tax, since it draws, as a single, extraordinary levy, on the increase in the assets, which usually becomes the source of the collection of this tax. For a relatively long time inheritance and gift tax had not occurred in the Polish tax system as a separate tax. It was however part of an entirely different property rights acquisition tax. It reemerged as a separate inheritance and gift tax in 1975 and is now regulated according to an act of July 28,1983, which has been frequently amended. II Inheritance and gift tax is a levy imposed solely on individuals for only persons can be, since 1990, payers of this tax. In respect to a type 176 ANTONI HANUSZ of personal bond between the vendee and the person from whom or after whom the property or the rights to property have been acquired, the bond being kinship or adoption, the payers of this tax can be divided into three groups. -

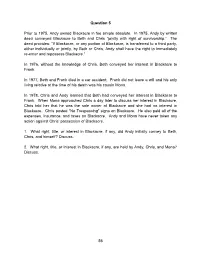

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy Owned Blackacre in Fee Simple Absolute. In

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute. In 1975, Andy by written deed conveyed Blackacre to Beth and Chris “jointly with right of survivorship.” The deed provides: “If Blackacre, or any portion of Blackacre, is transferred to a third party, either individually or jointly, by Beth or Chris, Andy shall have the right to immediately re-enter and repossess Blackacre.” In 1976, without the knowledge of Chris, Beth conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. In 1977, Beth and Frank died in a car accident. Frank did not leave a will and his only living relative at the time of his death was his cousin Mona. In 1978, Chris and Andy learned that Beth had conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. When Mona approached Chris a day later to discuss her interest in Blackacre, Chris told her that he was the sole owner of Blackacre and she had no interest in Blackacre. Chris posted “No Trespassing” signs on Blackacre. He also paid all of the expenses, insurance, and taxes on Blackacre. Andy and Mona have never taken any action against Chris’ possession of Blackacre. 1. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, did Andy initially convey to Beth, Chris, and himself? Discuss. 2. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, are held by Andy, Chris, and Mona? Discuss. 56 Answer A to Question 5 1. WHAT RIGHT, TITLE OR INTEREST IN BLACKACRE DID ANDY INITIALLY CONVEY TO BETH, CHRIS, AND HIMSELF? Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute, which indicates absolute ownership and means he had the full right to convey Blackacre. -

Efficiency, Utility, and Wealth Maximization Jules L

Hofstra Law Review Volume 8 | Issue 3 Article 3 1980 Efficiency, Utility, and Wealth Maximization Jules L. Coleman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Recommended Citation Coleman, Jules L. (1980) "Efficiency, Utility, and Wealth Maximization," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 8: Iss. 3, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol8/iss3/3 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coleman: Efficiency, Utility, and Wealth Maximization EFFICIENCY, UTILITY, AND WEALTH MAXIMIZATION Jules L. Coleman* CONTENTS I. EFFICIENCY AND UTILITY ......................... 512 A. The Pareto Criteria ............................ 512 B. Kaldor-Hicks ........................... 513 C. The Pareto Standards and Utilitarianism ......... 515 1. Pareto Superiority ......................... 515 2. Pareto Optimality ......................... 517 D. Kaldor-Hicks and Utility ....................... 518 II. THE CONCEPTUAL BASIS OF WEALTH MAXIMIZATION . 520 A. Wealth and Efficiency ......................... 521 B. Consequences of the Reliance of Wealth on Prices . 523 1. Exchange ................................ 523 2. Scarcity .................................. 524 3. Theoretical Incompleteness ................. 524 4. Assigning Basic Entitlements ............... 524 5. Circularity -

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013 QUESTION 1 Moe, the owner of Blackacre, a single-family home, told Curly that he wanted to sell Blackacre for $300,000. Curly said to Moe that he would try to find a purchaser if Moe would agree to pay him a commission of 6%, and Moe orally agreed. Curly is not a licensed real estate broker. Thereafter, without Curly’s knowledge, Moe and Larry entered into negotiations for the sale of Blackacre. Larry faxed to Moe a signed letter stating that he offered to buy Blackacre for $250,000 in cash to be paid at the closing to take place in 90 days. The letter described Blackacre by street address and dimensions. Moe responded by mailing a signed letter to Larry stating that he was refusing Larry’s offer but would agree to sell Blackacre to him for $275,000 on the same terms. Larry immediately responded by mailing a signed letter to Moe stating that he agreed to the higher price. Before Moe received that letter from Larry, Curly presented Moe with a proposed contract for the sale of Blackacre to another prospective buyer for $300,000. Moe immediately sent a letter by fax to Larry stating that he was no longer willing to sell him Blackacre. Larry received this letter before Moe received Larry’s letter agreeing to the higher price. Larry then called Moe to confirm his willingness to buy Blackacre for $275,000, but Moe said he was now unwilling to sell Blackacre to him. -

Professor Crusto

Crusto, Personal Property: Adverse Possession, Bona Fide Purchaser, and Entrustment New Admitted Assignment, Monday, May 11, 2020 ************************************** Please kindly complete in writing and kindly prepare for discussion for the online class on Friday, May 15, 2020, the following exercises: I. Reading Assignments (see attached below, following Crusto’s lecture notes): 1. Adverse Possession, Bona Fide Purchaser, Entrustment: pp. 116-118, 151-163: O’Keeffe v. Snyder (see attachment) and 2. Crusto’s Notes (below) II. Exercises: Exercise 1 Based on the cases and the reading assignment (above) and Crusto lecture notes (below), write an “outline” listing five legal issues for the personal property topics of 1. Adverse Possession, Bona Fide Purchaser, and Entrustment, and ten rules and authorities (one word case name or other source). Exercise 2 Answer the following questions, providing a one sentence answer for each question: 1. Provide three examples of personal (not real) property. 2. What are the indicia (evidence) of ownership of personal property? 3. How does a person normally acquire title to personal property? 4. What role does possession play in evidencing ownership of personal property? 5. What is meant by the maxim that “possession is 9/10s of the law”? 6. How, if ever, can a person acquire title to personal property by adverse possession? 7. What is a statute of limitations? 8. What role did the statute of limitations play in the O’Keefe case? 9. How does a person qualify as a bona fide purchaser? 10. What benefits result from such a qualification? 11. What is the rule of discovery? 12. -

Steps for Creating a Deed of Gift

STEPS FOR CREATING A DEED OF GIFT This worksheet defines the steps for creating a Deed of Gift template. A Deed of Gift is a formal and legal agreement between a donor and a repository, that transfers ownership of and legal rights to the donated materials. Deeds of Gift help build a relationship of trust between an institution and a donor by setting the expectations and conditions an institution must meet as it assumes responsibility and ownership of a collection. Deeds of Gift state what is being donated, who is granting permission for the transfer, and any special rules concerning the access and use of a collection. Deeds of Gift are important in that once signed by both parties, they establish and govern the legal relationship between donor and repository and the legal status of the materials. Follow the steps below to create a template for a deed of gift between your institution and a donor. 1. Give the deed a title Include the name of your institution and “Deed of Gift”. Remember, you will want to give a copy of this document to a donor. Adding a clear, simple title will help donors and their descendants identify the function and importance of this record. Example: Deed of Gift Washington State University Libraries 2. Write a basic statement establishing the transfer of materials to the repository This consists of a generic statement that includes the transfer of ownership and intellectual property rights from the donor to the institution. This statement can be edited depending on the actual agreement made with the donor.