Femmes, Sport Et Médiatisation En Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’S Football, 1966-1999

Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 Downloaded from: https://research.chalmers.se, 2021-09-30 11:41 UTC Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Svensson, D., Oppenheim, F. (2018) Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 The International journal of the history of sport, 35(6): 575-590 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. research.chalmers.se offers the possibility of retrieving research publications produced at Chalmers University of Technology. It covers all kind of research output: articles, dissertations, conference papers, reports etc. since 2004. research.chalmers.se is administrated and maintained by Chalmers Library (article starts on next page) The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999 Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim To cite this article: Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim (2019): Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 -

Football League Tables 29 April

Issued Date Page England Top Leagues 2019 - 2020 29/04/2021 10:45 1/66 England - Premier League 20/21 England - Championship 20/21 P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES 1 ● MAN. CITY 33 24 5 4 69:24 12 2 3 37:15 12 3 1 32:9 77 Cl L W W 1 ● NORWICH 44 28 9 7 69:33 13 6 3 35:14 15 3 4 34:19 93 Pro D W W 2 ● MAN. UTD 33 19 10 4 64:35 9 3 4 34:21 10 7 0 30:14 67 Cl W W W 2 ● WATFORD 44 26 10 8 61:28 18 2 2 42:12 8 8 6 19:16 88 Pro W D W 3 ● LEICESTER 33 19 5 9 60:38 9 1 7 30:22 10 4 2 30:16 62 Cl W W L 3 ● BRENTFORD FC 44 22 15 7 74:41 11 9 2 37:20 11 6 5 37:21 81 Pro Pl D W D 4 ● CHELSEA 33 16 10 7 51:31 7 6 3 27:16 9 4 4 24:15 58 Cl W D L 4 ● BOURNEMOUTH 44 22 11 11 73:43 13 3 6 40:22 9 8 5 33:21 77 Pro Pl W W W 5 ● WEST HAM 33 16 7 10 53:43 9 4 4 29:21 7 3 6 24:22 55 Uefa L D W 5 ● SWANSEA 44 22 11 11 54:36 11 6 5 25:15 11 5 6 29:21 77 Pro Pl L W W 6 ● LIVERPOOL 33 15 9 9 55:39 8 3 6 25:20 7 6 3 30:19 54 L W W 6 ● BARNSLEY 44 23 8 13 56:46 12 5 5 28:20 11 3 8 28:26 77 Pro Pl D W W 7 ● TOTTENHAM 33 15 8 10 56:38 8 3 5 28:18 7 5 5 28:20 53 L W D 7 ● READING 44 19 12 13 59:48 12 3 7 35:25 7 9 6 24:23 69 D W L 8 ● EVERTON 32 15 7 10 44:40 5 4 7 22:25 10 3 3 22:15 52 L L D 8 ▼ CARDIFF CITY 44 17 13 14 61:48 8 5 9 36:25 9 8 5 25:23 64 L L D 9 ▼ LEEDS 33 14 5 14 50:50 6 5 6 22:19 8 0 8 28:31 47 D W W 9 ▼ MIDDLESBROUGH 44 18 9 17 54:49 11 4 7 30:22 7 5 10 24:27 63 L D L 10 ▲ ARSENAL 33 13 7 13 44:37 6 4 7 19:20 7 3 6 25:17 46 W D L 10 ▲ Q.P.R. -

Felix Michel Till AFC Under 2021

Pressmeddelande 2021-08-11 Felix Michel till AFC under 2021 AIK Fotboll är överens med Athletic FC Eskilstuna om ett lån av den libanesiske landslagsmannen Felix Michel. Lånet gäller från idag och fram till och med den 31 december 2021. – Prioriterat för oss båda har varit att finna en lösning där Felix får större möjlighet till kontinuerlig speltid. Det tror vi att Felix kan få i en miljö som han är väl bekant med sedan tidigare, säger herrlagets sportchef Henrik Jurelius. För en längre faktapresentation av Felix Michel, se det bifogade materialet i detta pressmeddelande. För mer information, kontakta: Henrik Jurelius, sportchef (herr) AIK Fotboll Mobil: 070 - 431 12 02 E-post: [email protected] Om AIK Fotboll AB AIK Fotboll AB bedriver AIK Fotbollsförenings elitfotbollsverksamhet genom ett herrlag, damlag samt ett juniorlag för herrar. 2021 spelar herrlaget i Allsvenskan, damlaget i OBOS Damallsvenskan och juniorlaget, som utgör en viktig rekryteringsgrund för framtida spelare, spelar i P19 Allsvenskan Norra. AIK Fotboll AB är noterat på NGM Nordic Growth Market Stockholm. För ytterligare information kring AIK Fotboll besök www.aikfotboll.se. Pressmeddelande 2021-08-11 Fakta Felix Michel 27-årige Felix Michel, född lördagen den 23 juli 1994 på Södertälje sjukhus, inledde som sjuåring sitt fotbolls- spelande i moderklubben Syrianska FC. Efter ungdoms- och juniorfotboll i Syrianska FC A-lagsdebuterade han 2013 för klubben och det blev spel i sex tävlingsmatcher under året. Felix spelade sammanlagt fyra säsonger med Syrianskas A-lag innan han i augusti 2016 skrev på ett avtal med den turkiska klubben Eskişehirspor som spelade i TFF First League, den näst högsta ligan i Turkiet. -

Record Book Wsoc 21.Pdf

QUICK FACTS GENERAL TEAM INFORMATION (continued) Location ...............................................................Birmingham, Ala. North Carolina (1) .....................................................................................Elliott Founded .................................................................................. 1969 Michigan (1) .............................................................................................Lipsey Enrollment ........................................................................... 22,563 Québec (1) .............................................................................................Barriere President ...................................................................Dr. Ray Watts South Carolina (1) .............................................................................Stephens Athletics Director ...................................................... Mark Ingram Texas (1) ................................................................................................. Presley Faculty Athletics Representative .......................Dr. Frank Messina Virginia (1) ...............................................................................................Kinnier Sport Administrator .............................................. Brad Hardekopf Hungary (1) ...................................................................................................Kiss Nickname ............................................................................ Blazers Slovakia (1) .....................................................................................Zemberyova -

L'évolution Démographique Des Principales Ligues De Football Féminin

Rapport mensuel de l’ Observatoire du football CIES n°66 - Juin 2021 L’évolution démographique des principales ligues de football féminin (2017-2021) Drs Raffaele Poli, Loïc Ravenel et Roger Besson 1. Introduction Figure 1 : nombre de joueuses par équipe dans les dix principales ligues féminines (2017-2021) L’engouement populaire suscité depuis les an- [2017] saison 2016/17 ou 2017 24.24 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| nées 2000 par les grandes manifestations entre [2018] saison 2017/18 ou 2018 24.98 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| équipes nationales de football féminines a for- tement stimulé les investissements aussi à [2019] saison 2018/19 ou 2019 25.39 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| l’échelle des clubs. En Europe notamment, de [2020] saison 2019/20 ou 2020 24.98 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| plus en plus d’équipes parmi les plus compéti- [2021] saison 2020/21 ou 2021 25.78 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| tives chez les hommes ont eu à cœur de mettre sur pied des équipes performantes également chez les femmes. La croissance économique du football féminin a amené plusieurs -

Ergebnisse Samstag, 25.09.2021 - Montag, 27.09.2021

Ergebnisse Samstag, 25.09.2021 - Montag, 27.09.2021 Fußball 1 Lyga Halbzeit Endstand G78 25.09. 18:00 FK Banga B : FK Vilnius BFA 1:0 1:0 1. CFL Halbzeit Endstand ABM 25.09. 18:00 FK Jezero Plav : FK Rudar Pljevlja 1:2 2:4 CD1 25.09. 19:00 FK Podgorica : FK Decic Tuzi 0:1 1:1 G378 26.09. 19:00 FK Mornar Bar : FK Sutjeska Niksic 0:2 0:2 CDKL 26.09. 20:00 OFK Petrovac : FK Buducnost 0:2 2:3 1. Division Halbzeit Endstand CFK 25.09. 14:00 Lyngby BK : Hvidovre IF 3:1 3:1 DGL 25.09. 15:00 Aalesunds FK : Strömmen IF 3:1 3:2 EHM 25.09. 15:00 KFUM Oslo : Grorud IL 0:0 2:0 FKN 25.09. 15:00 Ranheim IL : Aasane Fotball 2:0 2:2 GL1 25.09. 15:00 Sandnes Ulf : Stjördals-Blink FB 1:1 2:1 HM2 25.09. 15:00 Sogndal IL : Bryne FK 0:0 0:0 KN3 25.09. 15:00 Ullensaker/Kisa IL : Raufoss IL 0:1 0:2 L14 25.09. 15:00 BK Fremad Amager : Vendsyssel FF 0:0 1:0 BH9 25.09. 18:00 Aris Limassol FC : Anorth. Famagusta 3:1 3:2 AF1 25.09. 20:00 Cobh Ramblers : Bray Wanderers 0:0 1:2 KM1 26.09. 12:00 Igilik : Kyran Shymkent 0:1 0:4 F14 26.09. 14:00 Jammerbugt FC : Esbjerg FB 1:0 1:0 G25 26.09. 15:00 IK Start : Fredrikstad FK 2:4 2:6 K47 26.09. -

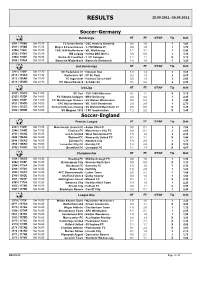

Results 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021

RESULTS 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021. Soccer-Germany Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2301 | 1358B Sat 15:30 FC Union Berlin - DSC Arminia Bielefeld 0:0 1:0 1 1,65 2303 | 1358D Sat 15:30 Bayer 04 Leverkusen - 1. FSV Mainz 05 0:0 1:0 1 1,70 2305 | 1358F Sat 15:30 TSG 1899 Hoffenheim - VfL Wolfsburg 1:1 3:1 1 2,50 2302 | 1358C Sat 15:30 RB Leipzig - Hertha BSC Berlin 3:0 6:0 1 1,30 2304 | 1358E Sat 15:30 Eintracht Frankfurt - 1. FC Cologne 1:1 1:1 X 3,75 2306 | 1359A Sat 18:30 Borussia M'gladbach - Borussia Dortmund 1:0 1:0 1 3,20 2nd Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2311 | 1359F Sat 13:30 SC Paderborn 07 - Holstein Kiel 1:0 1:2 2 3,65 2313 | 135AC Sat 13:30 Karlsruher SC - FC St. Pauli 0:2 1:3 2 2,85 2312 | 135AB Sat 13:30 FC Ingolstadt - Fortuna Düsseldorf 0:0 1:2 2 2,00 2314 | 135AD Sat 20:30 FC Hansa Rostock - Schalke 04 0:1 0:2 2 2,30 3rd Liga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2323 | 135CF Sat 14:00 SC Verl - TSV 1860 München 0:1 1:1 X 3,75 2325 | 135DF Sat 14:00 FC Viktoria Cologne - MSV Duisburg 2:0 4:2 1 2,45 2326 | 135EF Sat 14:00 FC Wurzburger Kickers - SV Wehen Wiesbaden 0:0 0:4 2 2,40 2321 | 135CD Sat 14:00 1 FC Kaiserslautern - VfL 1899 Osnabrück 2:0 2:0 1 2,70 2322 | 135CE Sat 14:00 Eintracht Braunschweig - SV Waldhof Mannheim 07 0:0 0:0 X 3,25 2324 | 135DE Sat 14:00 SV Meppen 1912 - 1 FC Saarbrucken 1:2 2:2 X 3,40 Soccer-England Premier League HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2347 | 1369F Sat 13:30 Manchester United FC - Aston Villa FC 0:0 0:1 2 7,00 2346 | 1369E Sat 13:30 Chelsea FC - Manchester City FC 0:0 0:1 2 2,60 2351 | 136AE Sat 16:00 Leeds United - West -

ERSÄTTNING Domare, Assisterande Domare Och Fjärdedomare Har Rätt Till Reseersättning

2021-01-29 FÖRESKRIFTER GÄLLANDE EKONOMISK ERSÄTTNING TILL DOMARE Förbundsserierna och övriga förbundstävlingar i fotboll Ersättning till domare, assisterande domare och fjärdedomare i förbundsserierna Allsvenskan–div. 3, herrar, Damallsvenskan–div. 1, damer, Svenska Cupen samt SEF U21-serier och ungdomsturneringar ska för spelåret 2021 utgå enligt nedan. MATCHARVODE Herrar Domare Assisterande domare Allsvenskan 9 170 kr 4 585 kr Superettan 4 895 kr 2 680 kr Ettan 2 490 kr 1 495 kr Div. 2 1 840 kr 1 100 kr Div. 3, SEF:s Folksam U21-serier, P19 Allsvenskan 1 390 kr 835kr P19 div 1, P17 Allsvenskan, Ligacupen P19 900 kr 655kr P17 div. 1, P16, Ligacupen P17 och P16 785 kr 575kr För fjärdedomare i Allsvenskan utgår arvode med 1 840 kr och i Superettan med 1 390 kr per match. Damer Damallsvenskan 2540 kr 1540 kr Elitettan Dam 1560 kr 905 kr Div. 1, damer 1130 kr 680 kr Svenska Spel F19 1130 kr 680 kr SM F17- slutspel (åttondelsfinaler, kvartsfinaler, semifinaler och final) 900 kr 655 kr SM F17-gruppspel 680 kr 495 kr För fjärdedomare i Damallsvenskan utgår arvode med 1 130 kr per match. Kvalspel Vid kvalspel utgår ersättning med ett belopp motsvarande det arvode som utgår i den serie som det laget med högst serietillhörighet tillhör. Svenska Cupen, herrar Ersättning utgår med belopp motsvarande det arvode som utgår i den serie som det lag med högst serietillhörighet tillhör, dock utgår ersättning som högst med ett belopp motsvarande match i Superettan. I semifinal och final utgår dock ersättning med ett belopp motsvarande match i Allsvenskan. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Bildandet Av Elitettan - Ett År Senare

Bildandet av Elitettan - ett år senare En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Lindgren, Louise Nygren, Josefin Åhlander, Sanna Idrottsvetenskapligt examensarbete (2IV31E) 15 högskolepoäng Datum: 22-05-14 Handledare: Tobias Stark Examinator: Per-Göran Fahlström Bildandet av Elitettan – ett år senare En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Abstrakt Titel: Bildandet av Elitettan – ett år senare - En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Författare: Louise Lindgren, Josefin Nygren & Sanna Åhlander Examinator: Per-Göran Fahlström Datum: 2014–05–22 Nyckelord: Elitettan, damfotboll, ekonomi, talangutveckling Problemområde: Elitettan är svensk fotbolls näst högsta serie på damsidan och denna spelades för första gången år 2013. Den nya rikstäckande serien innebar betydligt längre resor för seriens föreningar och således också en betydande ökning av resekostnaderna. Syfte: Syftet med studien är att undersöka organiseringen av elitverksamheten inom svensk damfotboll. Mer precist handlar det om att belysa betydelsen av omvandlingen av landets näst högsta serie, från två geografiskt uppdelade enheter – i form av en Söder- och en Norretta – till en enda riksomfattande serie, Elitettan. Ambitionen är att både jämföra synen på serieomläggningen på fältet och begrunda dess effekter för de inblandade föreningarna. Metod: Studien har genomförts som en kvalitativ intervjuundersökning som baseras på intervjuer med personer på ledande positioner i sju olika föreningar i Elitettan samt två utomstående personer, Hanna Marklund, expert på svensk damfotboll samt Anna Nilsson från intresseorganisationen Elitfotboll Dam. Resultat: Resultatet av studien visar det går att urskilja tydliga samband mellan synsättet på serieomläggningen och vilken historia samt var någonstans föreningarna befinner sig geografiskt. -

Table of Content

TABLE OF CONTENT PREFACE 7 1 INTRODUCTION 13 Prologue 13 Rationale 18 Aim 22 Framework 23 Disposition 24 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 27 Introduction 27 Gender Perspectives 28 A Development Approach 31 Promotion and Media Aspects of Women’s Football 35 Football and Identity Considerations 39 The Study’s Contribution 41 3 THEORETICAL VANTAGE POINT 43 Introduction 43 General Theoretical Approach 44 Brand Identity 48 Positioning 50 Communication 52 Case-Specific Theoretical Approaches 54 Combining General and Specific Theoretical Approaches 55 9 4 METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH 57 Research Design 57 The Embedded Multi-Case Approach 60 Selecting Suitable Informants 60 Mixed Methods for Attaining Empirical Data 63 Document Analysis 66 Qualitative Interviews 67 Quantitative Questionnaires 69 Observations 71 The Role of the Researcher 72 Reflections 72 Ethical Considerations 73 5 WOMEN’S FOOTBALL IN SCANDINAVIA 75 Setting the Scene 75 The Development of Women’s Football in Scandinavia 75 Sweden 78 Denmark 79 Norway 81 Contemporary Development for Scandinavian Women’s Football Clubs 82 Investigating Scandinavian Women’s Football Clubs 86 6 GENDER AS PART OF A FOOTBALL IDENTITY 89 The Case of Stabæk Football 89 Specific Theoretical Approach 91 Gender Constructions 91 Stabæk Football and the Geographical Setting 92 Stabæk, Always, Regardless – A Formulated Identity 94 Stabæk Football – Integrating Women and Men 100 Identity Conditions for Stabæk 108 Summary and Reflections 116 7 GENERATING ORGANISATIONAL VIABILITY THROUGH NETWORKING 121 The Case of Fortuna Hjørring -

Basic Knowledge About Swedish Professional Football

19 75 Average temperatures January July Malmö +31.6°F (-0.2°C) 62.2°F (+16.8°C) Stockholm +27.0°F (-2.8°C) 63.0°F (+17.2°C) Kiruna +3.2°F (-16.0°C) 55.0°F (+12.8°C) Daylight Januari 1 July 1 Malmö 7 hours 17 hours Stockholm 6 hours 18 hours Kiruna 0 hours 24 hours 2 Welcome to Sweden Spelarföreningen Fotboll i Sverige (SFS) would firstly Most important export goods: Machinery, electron- like to welcome you to Sweden. Established since ics and telecommunication, paper, pharmaceuticals, 1975 the Spelarföreningen has worked to improve the petroleum products, iron and steel, and foodstuffs playing conditions of all the players within Sweden. Most important imported goods: Electronics and Our dedicated team of representatives who are ex- telecommunication, machinery, foodstuffs, crude oil, professionals or still playing themselves are there to textiles and footwear, chemicals, pharmaceuticals help and answer your questions or concerns. If this and petroleum products is your first visit to Sweden let’s give you some basic information. There is so much more that we could tell you, but we will leave that up to your new club and team mates. Facts about Sweden But if you do need a little advice and help please read With a population of just over 9,3 million and 450 on to the next pages where we tell you what we can 000 km2 to live in, the third largest country in do for you. Western Europe, Forests: 53%, Mountains: 11%, Cultivated land: 8%, Lakes and rivers: 9%.