Gatekeeping in the Coverage of Interethnic Conflicts: an Analysis of Mainstream and Alternative Newspapers in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

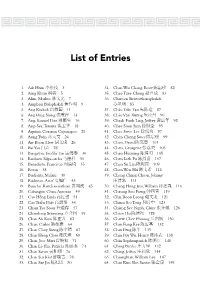

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Jenis Media Tajuk Berita Harian Azmin Jawab Hadi Berita Harian

Jenis Media Tajuk Berita Harian Azmin jawab Hadi Berita Harian Cacat penglihatan tetapi celik ilmu Berita Harian Polis nafi keluar kenyataan roboh kuil Batu Caves Berita Harian Masalah sampah di Kuala Langat membimbangkan Berita Harian Hampir 300 belia didedah peluang kerjaya Berita Harian Kebersihan Bandar Baru Bangi semakin merosot Berita Harian The Titans turun tempang Utusan Malaysia Hudud bukan dasar Pakatan Utusan Malaysia Tiada permohonan tukar status kedai kepada gereja Utusan Malaysia Arahan roboh kuil Batu Caves palsu -KPN Utusan Malaysia Kerjasama Serantau Utusan Malaysia Pengarah JPNIN Sabah terima Anugerah Khas JPM 2014 Utusan Malaysia Tindakan Utusan Malaysia Curi air: Syabas rugi RM4.7 juta Utusan Malaysia Syabas cadang badan bebas siasat paip pecah di Bukit Bintang Utusan Malaysia - Supplement Reka bentuk seksi, ikonik Harian Metro Terminal seksa Harian Metro Tak sangup tunggu setahun Harian Metro Periksa lebih kerap Harian Metro Kereta berjoget Harian Metro Buaian jahanam nanti mangsa Harian Metro Menembak bersama APMM Harian Metro Tong sampah anti monyet Harian Metro Pertandingan landskap tonjol Ampang Jaya Harian Metro PKR setia bersama 2 parti Harian Metro Melimpah masuk rumah Harian Metro Azmin tolak dakwaan Hadi Sinar Harian PKR tolak alasan hudud demi keselamatan Sinar Harian Gereja dibenarkan pasang semula salib Sinar Harian Dilanda banjir kilat kali ketiga Sinar Harian Beri tempoh hingga hujung tahun Sinar Harian Jais mahu semuka Ekhsan Bukharee Sinar Harian Promosi bayaran kompaun MBSA Sinar Harian Ahli keluarga -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

23Rd AGM Minutes - 180614.Doc

TALIWORKS CORPORATION BERHAD (Company No. 6052-V) (Incorporated in Malaysia) MINUTES OF THE TWENTY THIRD ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF TALIWORKS CORPORATION BERHAD (“TALIWORKS” OR “THE COMPANY”) HELD AT BALLROOM 1, FIRST FLOOR, SIME DARBY CONVENTION CENTRE, 1A, JALAN BUKIT KIARA 1, 60000 KUALA LUMPUR ON WEDNESDAY, 18 JUNE 2014 AT 11:00 A.M. DIRECTORS : Y. Bhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Ong Ka Ting (Chairman and Senior Independent Non-Executive Director) : Mr. Lim Yew Boon (Executive Director) : Mr. Vijay Vijendra Sethu (Non-Independent Non- Executive Director Director) : Mr. Lim Chin Sean (Non-Independent Non-Executive Director) : Mr. Soong Chee Keong (Independent Non-Executive Director) MEMBERS, : As per Attendance Lists PROXY HOLDERS, CORPORATE REPRESENTATIVES, PRESS & INVITEES IN ATTENDANCE : Ms. Chua Siew Chuan (Company Secretary) CHAIRMAN Mr. Lim Yew Boon (“Mr. Lim”) introduced Y. Bhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Ong Ka Ting (“Tan Sri Chairman”) who was recently appointed as Chairman of the Company to all present. Tan Sri Chairman welcomed all present to the Twenty Third Annual General Meeting (“23rd AGM”) of the Company and called the Meeting to order at 11:00 a.m. QUORUM The requisite quorum being present pursuant to Article 58 of the Company's Articles of Association (“AA”), the Chairman declared the Meeting duly convened. NOTICE The Notice convening the Meeting dated 27 May 2014 having been circulated within the prescribed period, was with the permission of the Meeting, taken as read. Tan Sri Chairman proceeded to report on the performance of the Taliworks Group (“the Group”) for the financial year ended 31 December 2013 (“2013”). -

<Notes> Malaysia's National Language Mass Media

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository <Notes> Malaysia's National Language Mass Media : History Title and Present Status Author(s) Lent, John A. Citation 東南アジア研究 (1978), 15(4): 598-612 Issue Date 1978-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/55900 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University South East Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No.4, March 1978 Malaysia's National Language Mass Media: History and Present Status John A. LENT* Compared to its English annd Chinese language newspapers and periodicals, Nlalaysia's national language press is relatively young. The first recognized newspaper in the Malay (also called Bahasa Malaysia) language appeared in 1876, seven decades after the Go'vern ment Gazette was published in English, and 61 years later than the Chinese J!lonthly 1\1agazine. However, once developed, the Malay press became extremely important in the peninsula, especially in its efforts to unify the Malays in a spirit of national consciousness. Between 1876 and 1941, at least 162 Malay language newspapers, magazines and journals were published, plus eight others in English designed by or for Malays and three in Malay and English.I) At least another 27 were published since 1941, bringing the total to 200. 2) Of the 173 pre-World War II periodicals, 104 were established in the Straits Settlements of Singapore and Penang (68 and 36, respectively): this is understandable in that these cities had large concentrations of Malay population. In fact, during the first four decades of Malay journalism, only four of the 26 newspapers or periodicals were published in the peninsular states, all four in Perak. -

Conference Papers, Edited by Ramesh C

Quantity Meets Quality: Towards a digital library. By Jasper Faase & Claus Gravenhorst (Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Netherland) Jasper Faase Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Netherland Jasper Faase is a historian and Project Manager Digitization at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library of the Netherlands). Since 1999 Jasper has been involved in large scale digitization projects concerning historical data. In 2008 he joined the KB as coordinator of ‘Heritage of the Second World War’, a digitization programme that generated the following national collections: war diaries, propaganda material and illegally printed literature. He currently heads the Databank Digital Daily Newspapers project at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, as well as several other mass-digitization projects within the KB’s digitization department. Claus Gravenhorst CCS Content Conversion Specialists GmbH Claus Gravenhorst joined CCS Content Conversion Specialists GmbH in 1983, holds a diploma in Electrical Engineering (TU Braunschweig, 1983). Today he is the Director of Strategic Initiatives at CCS leading business development. For 10 years Claus was in charge of the product management of CCS products. During the METAe Project, sponsored by the European Union Framework 5, from 2000 to 2003 Claus collaborated with 16 international partners (Universities, Libraries and Research Institutions) to develop a conversion engine for books and journals. Claus was responsible for the project management, exploration and dissemination. The METAe Project was successfully completed in August 2003. Since 2003 he is engaged in Business Development and promoted docWORKS as a speaker on various international conferences and exhibitions. In 2006 Claus contributed as a co-author to “Digitalization - International Projects in Libraries and Archives”, published in June 2007 by BibSpider, Berlin. -

Malaysian Newspaper Discourse and Citizen Participation

www.ccsenet.org/ass Asian Social Science Vol. 8, No. 5; April 2012 Malaysian Newspaper Discourse and Citizen Participation Arina Anis Azlan (Corresponding author) School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-4456 E-mail: [email protected] Samsudin A. Rahim School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5832 E-mail: [email protected] Fuziah Kartini Hassan Basri School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5908 E-mail: [email protected] Mohd Safar Hasim Centre of Corporate Communications Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5540 E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 26, 2012 Accepted: March 13, 2012 Published: April 16, 2012 doi:10.5539/ass.v8n5p116 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n5p116 This project is funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia under the research code UKM-AP-CMNB-19-2009/1 Abstract Newspapers are a particularly important tool for the communication of government agenda, policies and issues to the general public. An informed public makes for better democracy and active citizen participation, with citizens able to make well-informed decisions about the governance of their nation. This paper observes the role of Malaysian mainstream newspapers in the facilitation of citizen participation to exercise their political rights and responsibilities through a critical discourse analysis on newspaper coverage of the New Economic Model (NEM), a landmark policy of the Najib Administration. -

Malaysia's National Language Mass Media: History and Present Status

South East Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No.4, March 1978 Malaysia's National Language Mass Media: History and Present Status John A. LENT* Compared to its English annd Chinese language newspapers and periodicals, Nlalaysia's national language press is relatively young. The first recognized newspaper in the Malay (also called Bahasa Malaysia) language appeared in 1876, seven decades after the Go'vern ment Gazette was published in English, and 61 years later than the Chinese J!lonthly 1\1agazine. However, once developed, the Malay press became extremely important in the peninsula, especially in its efforts to unify the Malays in a spirit of national consciousness. Between 1876 and 1941, at least 162 Malay language newspapers, magazines and journals were published, plus eight others in English designed by or for Malays and three in Malay and English.I) At least another 27 were published since 1941, bringing the total to 200. 2) Of the 173 pre-World War II periodicals, 104 were established in the Straits Settlements of Singapore and Penang (68 and 36, respectively): this is understandable in that these cities had large concentrations of Malay population. In fact, during the first four decades of Malay journalism, only four of the 26 newspapers or periodicals were published in the peninsular states, all four in Perak. The most prolific period in the century of Malay press is the 35 years between 1906-1941, when 147 periodicals were issued: however, in this instance, 68, or nearly one half, were published in the peninsular states. Very few of the publications lasted long, to the extent that today, in Malaysia, despite the emphasis on Malay as the national language, there are only three Malay dailies. -

Framing Interethnic Conflict in Malaysia: a Comparative Analysis of Newspaper Coverage on the Hindu Rights Action Force (Hindraf)

International Journal of Communication 6 (2012), 166–189 1932–8036/20120166 Framing Interethnic Conflict in Malaysia: A Comparative Analysis of Newspaper Coverage on the Hindu Rights Action Force (Hindraf) LAI FONG YANG Taylor's University Malaysia MD SIDIN AHMAD ISHAK University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur Despite repeated warnings from the Malaysian government, the Hindu Rights Action Force (Hindraf) rally drew thousands of Indians protesting on the streets of Kuala Lumpur on November 25, 2007. Mistreatment of Indians and lack of press coverage of their plight had been commonplace for years. By employing framing as the theoretical framework and content analysis as the research method, this study examines what perspectives newspapers have created that influence citizens’ understanding of the Hindraf movement. Three mainstream newspapers were found to focus on the conflict frame, and their representation of Hindraf articulated a hegemonic discourse that was prejudicial to the interests of the group and contrary to a spirit of democratic inquiry. The dissimilar coverage of the same issue by the alternative newspaper denoted that publication’s varied points of view, which were rooted in different political beliefs, cultural assumptions and institutional practices. Introduction Since gaining independence in 1957, the Malaysian government has viewed interethnic relations as a real challenge to the social stability of the country (Abdul Rahman, 2000; Baharuddin, 2005; Brown, 1994). As early as 1970, Mahathir Mohamad, who was then a medical doctor and later became the fourth and longest-serving prime minister of Malaysia, claimed that there was never true racial harmony in Malaysia. In his much-debated and once-banned book, The Malay Dilemma, he argued that although there was a certain amount of tolerance and accommodation, racial harmony in Malaysia was neither real nor Lai Fong Yang: [email protected] Md Sidin Ahmadd Ishak: [email protected] Date submitted: 2011–06–03 Copyright © 2012 (Lai Fong Yang & Md Sidin Ahmad Ishak). -

Foreign and Security Policy in the New Malaysia

Foreign and security policy in Elina Noor the New Malaysia November 2019 FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY IN THE NEW MALAYSIA The Lowy Institute is an independent policy think tank. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia — economic, political and strategic — and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high-quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Analyses are short papers analysing recent international trends and events and their policy implications. The views expressed in this paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute or the institutions with which the author is affiliated. FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY IN THE NEW MALAYSIA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia’s historic changE oF govErnment in May 2018 rEturnEd Former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad to ofFice supported by an eclectic coalition of parties and interests under the Pakatan Harapan (AlliancE of HopE) bannEr. This raisEd quEstions about how thE sElF-declared Malaysia Baharu (NEw Malaysia) would EngagE with thE rest of thE world. AftEr thE ElEction, it was gEnErally assumEd that Malaysia’s ForEign policy would largEly stay thE coursE, with some minor adjustments. This trajEctory was confirmEd with thE SEptembEr 2019 relEasE of thE Foreign Policy Framework of the New Malaysia: Change in Continuity, thE country’s First major Foreign policy restatement under the new government. -

Newpapers' Coverage During the Permatang Pauh By-Election

ISSC 2016 : International Soft Science Conference Newpapers’ Coverage During the Permatang Pauh By-Election Mohd Azizuddin Mohd Sani* * Corresponding author: Mohd Azizuddin Mohd Sani, [email protected] School of International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia Abstract http://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.110 This paper is based on a research about newspapers’ coverage during the Permatang Pauh By-Election which was held on 7 May 2015. Five newspapers were selected are the Utusan Malaysia, Berita Harian, Sinar Harian, New Straits Times and the Star. This research will determine the coverage of the press in term of biasness tendency toward political parties contested in the by-election. The Permatang Pauh by-election was contested by four candidates, consisting of former opposition leader Wan Azizah Wan Ismail from People’s Justice Party (PKR), Barisan Nasional (BN)’s Suhaimi Sabudin, Malaysia’s People’s Party (PRM)’s Azman Shah Othman and independent candidate Salleh Isahak. This by-election was won by Wan Azizah Wan Ismail. However, this research has been able to find the link between ownership with the biasness of print media toward political parties empirically. The finding is that all newspapers were bias toward the ruling BN, except for the Sinar Harian which was balance in its coverage. © 2016 Published by Future Academy www.FutureAcademy.org.uk Keywords: Permatang Pauh By-Election; Malaysia; Newspapers; Barisan Nasional; People’s Justice Party. 1. Introduction Permatang Pauh by-election was held for the Lower House (Dewan Rakyat) Parliamentary seat on 7 May 2015. The by-election was held after the seat was vacant. -

MDA Releases Rankings of Top Web Entities in Malaysia for December 2018

MDA Releases Rankings of Top Web Entities in Malaysia for December 2018 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29th March, 2019 – The Malaysian Digital Association (MDA), the apex representative body for online publishers, advertising agencies and digital service providers in Malaysia, today released monthly rankings of web activity for the top online entities in Malaysia for December 2018 based on data from Comscore MMX Multi-Platform®. Comscore MMX Multi- Platform provides an unduplicated view of total audience behavior across desktops, smartphones and tablets to give a deep look at audience size, demographic composition, engagement, and behavioral trends. Top 20 Malaysia-based Domains Visited in Malaysia BHARIAN.COM.MY took the top position again in the 20 local domains ranking in December 2018, with over 5 million unique visitors. KOSMO.COM.MY entered the top 20 ranking, featuring in position #17. Top 20 Local Domains visited in Malaysia^ December 2018 Total Malaysia – Desktop population age 6+, Mobile population age 18+ Source: Comscore MMX Multi-Platform Unique Visitors Unique Visitors Rank Entity Rank Entity (000) (000) 1 BHARIAN.COM.MY 5,090 11 UTUSAN.COM.MY 3,081 2 MAYBANK2U.COM.MY 4,688 12 ORIENTALDAILY.COM.MY 3,073 3 HMETRO.COM.MY 4,631 13 CHINAPRESS.COM.MY 2,967 4 ASTROAWANI.COM 4,121 14 SAYS.COM 2,896 5 MALAYSIAKINI.COM 4,047 15 CIMBCLICKS.COM.MY 2,224 6 DIGI.COM.MY 3,939 16 OHBULAN.COM 2,016 7 MUDAH.MY 3,777 17 KOSMO.COM.MY 1,777 8 THESTAR.COM.MY 3,747 18 NST.COM.MY 1,747 9 SINARHARIAN.COM.MY 3,278 19 PAULTAN.ORG 1,705 10 SINCHEW.COM.MY 3,238 20 LOWYAT.NET 1,614 ^According to MDA’s custom-defined ranking based on Comscore MMX Multi-Platform data.