Assata Shakur: the Battle for Memory in the Imagined Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church Model

Women Who Lead Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church model: ● “A predominantly female membership with a predominantly male clergy” (159) Competition: ● “Black Panther Party...gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead...than any of its contemporaries” (161) “We Want Freedom” (pt. 2) Invisibility does not mean non existent: ● “Virtually invisible within the hierarchy of the organization” (159) Sexism does not exist in vacuum: ● “Gender politics, power dynamics, color consciousness, and sexual dominance” (167) “Remembering the Black Panther Party, This Time with Women” Tanya Hamilton, writer and director of NIght Catches Us “A lot of the women I think were kind of the backbone [of the movement],” she said in an interview with Michel Martin. Patti remains the backbone of her community by bailing young men out of jail and raising money for their defense. “Patricia had gone on to become a lawyer but that she was still bailing these guys out… she was still their advocate… showing up when they had their various arraignments.” (NPR) “Although Night Catches Us, like most “war” films, focuses a great deal on male characters, it doesn’t share the genre’s usual macho trappings–big explosions, fast pace, male bonding. Hamilton’s keen attention to minutia and everydayness provides a strong example of how women directors can produce feminist films out of presumably masculine subject matter.” “In stark contrast, Hamilton brings emotional depth and acuity to an era usually fetishized with depictions of overblown, tough-guy black masculinity.” In what ways is the Black Panther Party fetishized? What was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense? The Beginnings ● Founded in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali. -

JOANNE DEBORAH CHESIMARD Act of Terrorism - Domestic Terrorism; Unlawful Flight to Avoid Confinement - Murder

JOANNE DEBORAH CHESIMARD Act of Terrorism - Domestic Terrorism; Unlawful Flight to Avoid Confinement - Murder Photograph Age Progressed to 69 Years Old DESCRIPTION Aliases: Assata Shakur, Joanne Byron, Barbara Odoms, Joanne Chesterman, Joan Davis, Justine Henderson, Mary Davis, Pat Chesimard, Jo-Ann Chesimard, Joanne Debra Chesimard, Joanne D. Byron, Joanne D. Chesimard, Joanne Davis, Chesimard Joanne, Ches Chesimard, Sister-Love Chesimard, Joann Debra Byron Chesimard, Joanne Deborah Byron Chesimard, Joan Chesimard, Josephine Henderson, Carolyn Johnson, Carol Brown, "Ches" Date(s) of Birth Used: July 16, 1947, August 19, 1952 Place of Birth: New York City, New York Hair: Black/Gray Eyes: Brown Height: 5'7" Weight: 135 to 150 pounds Sex: Female Race: Black Citizenship: American Scars and Marks: Chesimard has scars on her chest, abdomen, left shoulder, and left knee. REWARD The FBI is offering a reward of up to $1,000,000 for information directly leading to the apprehension of Joanne Chesimard. REMARKS Chesimard may wear her hair in a variety of styles and dress in African tribal clothing. CAUTION Joanne Chesimard is wanted for escaping from prison in Clinton, New Jersey, while serving a life sentence for murder. On May 2, 1973, Chesimard, who was part of a revolutionary extremist organization known as the Black Liberation Army, and two accomplices were stopped for a motor vehicle violation on the New Jersey Turnpike by two troopers with the New Jersey State Police. At the time, Chesimard was wanted for her involvement in several felonies, including bank robbery. Chesimard and her accomplices opened fire on the troopers. One trooper was wounded and the other was shot and killed execution-style at point-blank range. -

SEVEN STORIES PRESS 140 Watts Street

SEVEN STORIES PRESS 140 Watts Street New York, NY 10013 BOOKS FOR ACADEMIC COURSES 2019 COURSES ACADEMIC FOR BOOKS SEVEN STORIES PRESS STORIES SEVEN SEVEN STORIES PRESS BOOKS FOR ACADEMIC COURSES 2020 SEVEN STORIES PRESS TRIANGLE SQUARE SIETE CUENTOS EDITORIAL BOOKS FOR ACADEMIC COURSES 2020–2021 “Aric McBay’s Full Spectrum Resistance, Volumes One and Two “By turns humorous, grave, chilling, and caustic, the stories and are must reads for those wanting to know more about social essays gathered in [Crossing Borders] reveal all the splendors movement theory, strategies and tactics for social change, and and all the miseries of the translator’s task. Some of the most the history and politics of activism and community organizing. distinguished translators and writers of our times offer reflections There is nothing within the realm of social justice literature that that deepen our understanding of the delicate and some- matches the breadth of modern social movements depicted in times dangerous balancing act that translators must perform. these books. These are engaging, critical, exciting, and outstand- Translators are often inconspicuous or unnoticed; here we have ing intersectional books that respectfully speak about the pitfalls a chance to peer into the realities and the fantasies of those who and successes for social change.” live in two languages, and the result is altogether thrilling and —ANTHONY J. NOCELLA II, assistant professor of criminology, instructive.” Salt Lake Community College, and co-editor of Igniting a Revolution: —PETER CONNOR, director of the Center for Translation Studies, Voices in Defense of the Earth Barnard College “By placing readers into an intimate conversation with one of “For large swaths of the body politic, the December 2016 US this country’s most important thinkers, as well as members of the elections offered up the prospect of a long and dark winter in Occupy Wall Street movement, Wilson and Gouveia provide a America. -

The Revolutionary Nationalist Leadership of Malcolm X and the Rise of National Liberation Movements Worldwide Fighting U,S

The revolutionary nationalist leadership of Malcolm X and the rise of national liberation movements worldwide fighting u,s. imperialism in the 1950's propelled the Black liberation struggle from a movement for civil rights to a struggle for human rights, Black power and self-determination, Revolutionary organizations such as the Black Panther Party (B.P.P.) and the Revolutionary Action Movement (R.A.M.) emerged to lead Black people to fight for liberation against u.s. imperialism and all its repressive forces, It was the Panthers who gave political leadership in defining the police as pigs and enemies of all people. The establishment of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika in 1968 named the national territory of the New Afrikan nation and fought that land and independence would be the only strategy for freedom, The Black liberation struggle led in the building of anti-imperialist struggle in this country and led the call to build solidarity with the Vietnamese nation in its fight for national liberation and socialism, It was this clear identification of u.s. imperialism as the enemy of Third World nations and progressive white people that organized millions of white people to build a massive anti- imperialist student movement and gave power to the building of the anti- imperialist struggle for women's liberation and gay liberation as well. This movement also engaged in many militant and armed actions against the u.s. imperialist state and in support of Vietnam and the Black liberation struggle. The u.s. government unleashed its COINTELPRO war against the Black liberation struggle to attempt to destroy it by attacking organizations and frame-ups, jailings and murders of thousands of Black activists, The government attempted to portray the Panthers and the Black Liberation Army as "mad dogs" and "criminals" and consolidate support among white people for this fbi/police counterinsurgency warfare. -

Black Revolutionary Icons and `Neoslave' Narratives

Social Identities, Volume 5, N um ber 2, 1999 B lack Revolutionary Icons and `N eoslave ’ Narrative s JOY JAMES U niversity of C olorado Over the centuries that America enslaved Blacks, those men and women most determined to win freedom became fugitives, ¯ eeing from the brutal captivity of slavery . Many of their descendants who fought the Black liberation struggle also became fugitives. These men and women refused to endure the captivity awaiting them in retaliation for their systematic effort to win freedom. But unlike runaway slaves, these men and women fought for a more expansive freedom, not merely as individuals, but for an entire nation, and sought in the face of interna- tionally overwhelming odds to build a more humane and democratic political order. (Kathleen Neal Cleaver, 1988) As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole consciousness is, of course, revolution. (George Jackson, 1972) Neoslave Narrative s Historically, African Americans have found themselves corralled into dual and con¯ ictual roles, functioning as either happy or sullen slaves in compliant conformity or happy or sullen rebels in radical resistance to racial dominance. The degree to which historical slave narratives continue to shape the voices of their progeny rem ains the object of some speculation. In his introduction to Live from Death Row: This is M umia Abu-Jam al,1 John Edgar Widem an argues that many Americans continue to encounter black life and political struggles through the `neoslave narrative’ (popularise d in the 1970s by the television miniseries Roots based on Alex Haley’s ® ctional text of the same title). -

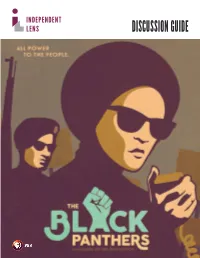

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using this Guide 1 From the Filmmaker 2 The Film 3 Framing the Context of the Black Panther Party 4 Frequently Asked Questions 6 The Black Panther Party 10-Point Platform 9 Background on Select Subjects 10 Planning Your Discussion 13 In Their Own Words 18 Resources 19 Credits 21 DISCUSSION GUIDE THE BLACK PANTHERS Using This Guide This discussion guide will help support organizations hosting Indie Lens Pop-Up events for the film The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, as well as other community groups, organizations, and educators who wish to use the film to prompt discussion and engagement with audiences of all sizes. This guide is a tool to facilitate dialogue and deepen understanding of the complex topics in the film The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. It is also an invitation not only to sit back and enjoy the show, but also to step up and take action. It raises thought-provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply and spark conversations with one another. We present suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also include valuable resources and Indie Lens Pop-Up is a neighborhood connections to organizations on the ground series that brings people together for that are fighting to make a difference. film screenings and community-driven conversations. Featuring documentaries seen on PBS’s Independent Lens, Indie Lens Pop-Up draws local residents, leaders, and organizations together to discuss what matters most, from newsworthy topics to family and relationships. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Support the Struggle for Black People's Human Rights! Independence for the New Afrikan Nation!

SUPPORT THE STRUGGLE FOR BLACK PEOPLE'S HUMAN RIGHTS! INDEPENDENCE FOR THE NEW AFRIKAN NATION! published by the John Brown Book Club TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 . EDITORIAL The Black Nation's Struggle for Land and Independence —PFOC Statement p. 1 2. 'LAW AND ORDER': Blueprint for Fascism (PFOC) p. 2 3 . ASSATA IS FREE! BLA Communique p. 12 Statement from Assata Shakur p. 13 4 . PUERTO RICO: DE PIE Y EN GUERRA PROTECT AND DEFEND THE ARMED CLANDESTINE MOVEMENT "A Nuestro Pueblo" —reprinted from El Nuevo Dia p. 16 Statement by the Liga Socialista Puertorriquefla p. 17 Statement by the Movimiento de Liberaci6n Nacional p. 18 Vieques: There's No Turning Back (PFOC) p. 19 5 . FREE LEONARD PELTIER! p. 22 Statements by Leonard Peltier —reprinted from Crazy Horse Spirit published by the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee p. 23 6. FREE the RNA-11: FREE THE LAND! p. 25 "RNA Freedom Fighters: A Continuing Episode of Human Rights Violations in Amerika" —reprinted from The New Afrikan published by the Republic of New Afrika p. 26 "Editorial: Denial of Self-Determination A New Afrikan View" —reprinted from The New Afrikan p. 31 7. FREE THE PONTIAC BROTHERS! "The People Are the Best Judges!" —reprinted from The FUSE published by the New Afrikan Prisoners Organization p. 34 8. REVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE IN GUYANA —by the Editors of Soulbook p. 38 Press Release, August 23, 1979 —Coalition for a Free Guyana p. 42 9 . A RESPONSE TO THE AFRICAN PEOPLES SOCIALIST PARTY —PFOC Statement p. 44 Breakthrough, political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, is published by John Brown Book Club. -

The Black Guerrilla Family in Context, 9 Hastings Race & Poverty L.J

Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Winter 2012 1-1-2012 Resistance and Repression: The lB ack Guerrilla Family in Context Azadeh Zohrabi Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_race_poverty_law_journal Part of the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Azadeh Zohrabi, Resistance and Repression: The Black Guerrilla Family in Context, 9 Hastings Race & Poverty L.J. 167 (2012). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_race_poverty_law_journal/vol9/iss1/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resistance and Repression: The Black Guerrilla Family in Context AZADEH ZOHRABI* Introduction The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation ("CDCR") has identified prison gangs as "a serious threat to the safety and security of California prisons."' In response to this safety concern, the CDCR has developed a "gang validation" system to identify suspected prison gang members and associates and to administratively segregate them from the general population by holding them for years in harsh, highly restrictive security facilities, often referred to secure housing units ("SHUs"). This note examines CDCR's gang validation process as applied to the Black Guerrilla Family ("BGF"), the only Black prison gang that CDCR recognizes. Initial research for this note revealed a glaring void in legal and scholarly writings about the BGF. This Note began with a focus on the serious constitutional issues raised by CDCR's gang validation policies and procedures as applied to Black inmates. -

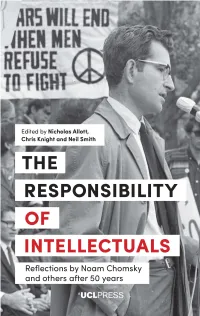

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

The Responsibility of Intellectuals EthicsTheCanada Responsibility and in the FrameAesthetics ofofCopyright, TranslationIntellectuals Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 ExploringReflections the by Work Noam of ChomskyAtxaga, Kundera and others and Semprún after 50 years HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme Edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Allott, N., Knight, C. and Smith, N. (eds). The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years. London: UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14324/ 111.9781787355514 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

Assata Shakur (Previously Joanne Chesimard) Made a Daring Escape from Prison in 1979, She—Like Our Fugitive Slave Ancestors—Became Legendary in the Black Community

,. :-V •:;..'/, BY CHERYLL Y. GREENE • - . WORD FROM A SISTERIN When revolutionary political activist Assata Shakur (previously JoAnne Chesimard) made a daring escape from prison in 1979, she—like our fugitive slave ancestors—became legendary in the Black community. Here she speaks about her life in Cuba today • Assata Shal£ur has been relentlessly called out of her name by government and law-enforcement agencies and the media. Branded "bank robber," "kidnapper," "murderer" and "soul of the Black Liberation Army" — an amorphous group the authorities claimed murdered police officers and pulled off bank robberies during the 1970V — Shakur,- now 40, calls herself a revolutionary fighter in thF ongoing struggle of Black people for political, social and economic justice. The chasm ' between those two perspectives reverberates with the historical antagonism between African America and America's ruling powers. As with Harriet Tubman and our myriad other fugitive slave ancestors, Assata Shakur is seen as someone to be protected or to be hunted, depending upon on which side of the Black community you're standing. To tell her side of it, Shakur has written the just published •' .--.. ' : i| Assata: An Autobiography (Lawrence Hill & Co.). (See excerpt on next page.) i ' v ;: ••' I Shakur's story reveals a rather typical girlhood and young womanhood in Black communities of North Carolina and New York City, where she was a sensitive, ' . .intense person trying to come to grips with being Black and female in a racist and sexist society. The turbulent -

The Black Liberation Army and the Paradox of Political Engagement” Is Forthcoming in Postcoloniality-Decoloniality-Black Critique: Joints and Fissures

““ IfIf wewe looklook closelyclosely wewe alsoalso seesee thatthat gen-gen- derder itselfitself cannotcannot bebe reconciledreconciled withwith aa slave’sslave’s genealogicalgenealogical isolation;isolation; that,that, forfor thethe Slave,Slave, therethere isis nono surplussurplus valuevalue toto bebe restoredrestored toto thethe timetime ofof labor;labor; thatthat nono treatiestreaties betweenbetween TTHETTHEHE BlacksBlacks andand HumansHumans areare inin WashingtonWashington BBLACKBBLACKLACK waitingwaiting toto bebe signedsigned andand ratifiratifi ed;ed; andand LLIBERATIONLLIBERATIONIBERATION that,that, unlikeunlike thethe SettlerSettler inin thethe NativeNative AARMYAARMYRMY AmericanAmerican politicalpolitical imagination,imagination, therethere isis &&&&TTHETTHEHE nono placeplace likelike EuropeEurope toto wwhichhich thethe SlaveSlave cancan PPARADOXPPARADOXARADOX returnreturn HumanHuman beings.beings. OOFOOFF PPOLITICALOLITICAL EENGAGEMENTEENGAGEMENTNGAGEMENT ILLILL WILLWILL EDITIONSEDITIONS ill-will-editions.tumblr.comill-will-editions.tumblr.com Frank B. Wilderson, III “The Black Liberation Army and the Paradox of Political Engagement” is forthcoming in Postcoloniality-Decoloniality-Black Critique: Joints and Fissures. Zine assembled in March 2014 based on an unoffi cial draft of the text. ill-will-editions.tumblr.com [email protected] 1 / THE BLACK LIBERATION ARMY WILDERSON / 38 THE BLACK LIBERATION ARMY & THE PARADOX OF POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT FRANK B. WILDERSON, III 37 / THE BLACK LIBERATION ARMY WILDERSON / 2 A BREAKBREAK ININ