ITEM 3 Propulsion Components and Equipment Propulsion Components And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propulsion Controls at NASA Lewis

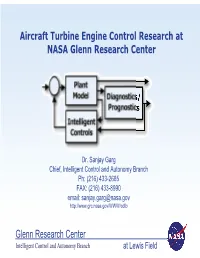

Aircraft Turbine Engine Control Research at NASA Glenn Research Center Dr. Sanjay Garg Chief, Intelligent Control and Autonomy Branch Ph: (216) 433-2685 FAX: (216) 433-8990 email: [email protected] http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/cdtb Glenn Research Center Intelligent Control and Autonomy Branch at Lewis Field Outline – The Engine Control Problem • Safety and Operational Limits • State-of-the-Art Engine Control Logic Architecture – Historical Glenn Research Center Contributions • Early Stages of Turbine Engine Control (1945-1960s) • Maturation of Turbine Engine Control (1970-1990) – Advanced Engine Control Research • Recent Significant Accomplishments (1990- 2004) • Current Research (2004 onwards) – Conclusion Glenn Research Center Intelligent Control and Autonomy Branch at Lewis Field Basic Engine Control Concept • Objective: Provide smooth, stable, and stall free operation of the engine via single input (PLA) with no throttle restrictions • Reliable and predictable throttle movement to thrust response • Issues: • Thrust cannot be measured • Changes in ambient condition and aircraft maneuvers cause distortion into the fan/compressor • Harsh operating environment – high temperatures and large vibrations • Safe operation – avoid stall, combustor blow out etc. • Need to provide long operating life – 20,000 hours • Engine components degrade with usage – need to have reliable performance throughout the operating life Glenn Research Center Intelligent Control and Autonomy Branch at Lewis Field Basic Engine Control Concept • Since Thrust (T) -

Turbopump Design and Analysis Approach for Nuclear Thermal Rockets

Turbopump Design and Analysis Approach for Nuclear Thermal Rockets Shu-cheng S. Chen1, Joseph P. Veres2, and James E. Fittje3 1NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44135 2Chief, Compressor Branch, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44135 3Analex Corporation, 1100 Apollo Drive, Brook Park, Ohio 44142 1(216) 433-3585, [email protected] Abstract. A rocket propulsion system, whether it is a chemical rocket or a nuclear thermal rocket, is fairly complex in detail but rather simple in principle. Among all the interacting parts, three components stand out: they are pumps and turbines (turbopumps), and the thrust chamber. To obtain an understanding of the overall rocket propulsion system characteristics, one starts from analyzing the interactions among these three components. It is therefore of utmost importance to be able to satisfactorily characterize the turbopump, level by level, at all phases of a vehicle design cycle. Here at NASA Glenn Research Center, as the starting phase of a rocket engine design, specifically a Nuclear Thermal Rocket Engine design, we adopted the approach of using a high level system cycle analysis code (NESS) to obtain an initial analysis of the operational characteristics of a turbopump required in the propulsion system. A set of turbopump design codes (PumpDes and TurbDes) were then executed to obtain sizing and performance characteristics of the turbopump that were consistent with the mission requirements. A set of turbopump analyses codes (PUMPA and TURBA) were applied to obtain the full performance map for each of the turbopump components; a two dimensional layout of the turbopump based on these mean line analyses was also generated. -

The Propulsion of Sea Ships – in the Past, Present and Future –

The Propulsion of Sea Ships – in the Past, Present and Future – (Speech by Bernd Röder on the occasion of the VHT General Meeting on 11.12.2008) To prepare for today’s topic, more specifically for the topic: ship propulsion of the future, I did what every reasonable person would have done in my situation if he should have a look into the future – I dug out our VHT crystal ball. As you know, our crystal ball is a reliable and cost-efficient resource which we have been using for a long time with great suc- cess. Among other things, we’ve been using it to provide you with the repair costs or their duration or the probable claims experience of a policy, etc. or to create short-term damage statistics, as well. So, I asked the crystal ball: What does ship propulsion of the future look like? Every future and all statistics lie in the crystal ball I must, however, admit that what I saw there was somewhat irritating, and it led me to only the one conclusion – namely, that we’re taking a look into the very distant future at a time in which humanity has not only used up all of the oil reserves but also the entire wind. This time, we’re not really going to get any further with the crystal ball. Ship propulsion of the future or 'back to the roots'? But, sometimes it helps to have a look into the past to be able to say something about the fu- ture. According to the principle, draw a line connecting the distant past to today and simply extend it into the future. -

Rocket Nozzles: 75 Years of Research and Development

Sådhanå Ó (2021) 46:76 Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-021-01584-6Sadhana(0123456789().,-volV)FT3](0123456789().,-volV) Rocket nozzles: 75 years of research and development SHIVANG KHARE1 and UJJWAL K SAHA2,* 1 Department of Energy and Process Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Guwahati 781039, India e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] MS received 28 August 2020; revised 20 December 2020; accepted 28 January 2021 Abstract. The nozzle forms a large segment of the rocket engine structure, and as a whole, the performance of a rocket largely depends upon its aerodynamic design. The principal parameters in this context are the shape of the nozzle contour and the nozzle area expansion ratio. A careful shaping of the nozzle contour can lead to a high gain in its performance. As a consequence of intensive research, the design and the shape of rocket nozzles have undergone a series of development over the last several decades. The notable among them are conical, bell, plug, expansion-deflection and dual bell nozzles, besides the recently developed multi nozzle grid. However, to the best of authors’ knowledge, no article has reviewed the entire group of nozzles in a systematic and comprehensive manner. This paper aims to review and bring all such development in one single frame. The article mainly focuses on the aerodynamic aspects of all the rocket nozzles developed till date and summarizes the major findings covering their design, development, utilization, benefits and limitations. -

Propulsion Systems for Aircraft. Aerospace Education II

. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 621 SE 017 458 AUTHOR Mackin, T. E. TITLE Propulsion Systems for Aircraft. Aerospace Education II. INSTITUTION 'Air Univ., Maxwell AFB, Ala. Junior Reserve Office Training Corps.- PUB.DATE 73 NOTE 136p.; Colored drawings may not reproduce clearly. For the accompanying Instructor Handbook, see SE 017 459. This is a revised text for ED 068 292 EDRS PRICE, -MF-$0.76 HC.I$6.97 Plus' Postage DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace 'Education; *Aerospace Technology;'Aviation technology; Energy; *Engines; *Instructional-. Materials; *Physical. Sciences; Science Education: Secondary Education; Textbooks IDENTIFIERS *Air Force Junior ROTC ABSTRACT This is a revised text used for the Air Force ROTC _:_progralit._The main part of the book centers on the discussion -of the . engines in an airplane. After describing the terms and concepts of power, jets, and4rockets, the author describes reciprocating engines. The description of diesel engines helps to explain why theseare not used in airplanes. The discussion of the carburetor is followed byan explanation of the lubrication system. The chapter on reaction engines describes the operation of,jets, with examples of different types of jet engines.(PS) . 4,,!It********************************************************************* * Documents acquired by, ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other souxces. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copravailable. nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document" Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. -

Development of Turbopump for LE-9 Engine

Development of Turbopump for LE-9 Engine MIZUNO Tsutomu : P. E. Jp, Manager, Research & Engineering Development, Aero Engine, Space & Defense Business Area OGUCHI Hideo : Manager, Space Development Department, Aero Engine, Space & Defense Business Area NIIYAMA Kazuki : Ph. D., Manager, Space Development Department, Aero Engine, Space & Defense Business Area SHIMIYA Noriyuki : Space Development Department, Aero Engine, Space & Defense Business Area LE-9 is a new cryogenic booster engine with high performance, high reliability, and low cost, which is designed for H3 Rocket. It will be the first booster engine in the world with an expander bleed cycle. In the designing process, the performance requirements of the turbopump and other components can be concurrently evaluated by the mathematical model of the total engine system including evaluation with the simulated performance characteristic model of turbopump. This paper reports the design requirements of the LE-9 turbopump and their latest development status. Liquid oxygen 1. Introduction turbopump Liquid hydrogen The H3 rocket, intended to reduce cost and improve turbopump reliability with respect to the H-II A/B rockets currently in operation, is under development toward the launch of the first H3 test rocket in FY 2020. In rocket development, engine is an important factor determining reliability, cost, and performance, and as a new engine for the H3 rocket first stage, an LE-9 engine(1) is under development. A rocket engine uses a turbopump to raise the pressure of low-pressure propellant supplied from a tank, injects the pressurized propellant through an injector into a combustion chamber to combust it under high-temperature and high- pressure conditions. -

Study and Numerical Simulation of Unconventional Engine Technology

STUDY AND NUMERICAL SIMULATION OF UNCONVENTIONAL ENGINE TECHNOLOGY by ANJALI SHEKHAR B.E Aeronautical Engineering VTU, Karnataka, 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Aerospace Engineering, College of Engineering and Applied Science, University of Cincinnati, Ohio 2018 Thesis Committee: Chair: Ephraim Gutmark, Ph.D. Member: Shaaban Abdallah, Ph.D. Member: Mark Turner, Sc.D. An Abstract of Study and Numerical Simulation of Unconventional Engine Technology by Anjali Shekhar Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Aerospace Engineering University of Cincinnati December 2018 The aim of this thesis is to understand the working of two unconventional aircraft propul- sion systems and to setup a two-dimensional transient simulation to analyze its operational mechanism. The air traffic has nearly increased by about 40% in past three decades and calls for alternative propulsion techniques to replace or support the current traditional propulsion methodology. In the light of current demand, the thesis draws motivation from renewed inter- est in two non-conventional propulsion techniques designed in the past and had not been given due importance due to various flaws/drawbacks associated. The thesis emphasizes on the work- ing of Von Ohains thermal compression engine and pulsejet combustors. Computational Fluid Dynamics is used in current study as it offers very high flexibility and can be modified easily to incorporate the required changes. Thermal Compression engine is a design suggested by Von Ohain in 1948. The engine works on the principle of pressure rise caused inside the engine which completely depends on the temperature of working fluid and independent of rotations per minute. -

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines John Schenderlein1, and Tyler Clayton2 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 80304 Although they garnish less attention than their flashy jet cousins, turboshaft engines hold a specialized niche in the aviation industry. Built to be compact, efficient, and powerful, turboshafts have made modern helicopters and the feats they accomplish possible. First implemented in the 1950s, turboshaft geometry has gone largely unchanged, but advances in materials and axial flow technology have continued to drive higher power and efficiency from today's turboshafts. Similarly to the turbojet and fan industry, there are only a handful of big players in the market. The usual suspects - Pratt & Whitney, General Electric, and Rolls-Royce - have taken over most of the industry, but lesser known companies like Lycoming and Turbomeca still hold a footing in the Turboshaft world. Nomenclature shp = Shaft Horsepower SFC = Specific Fuel Consumption FPT = Free Power Turbine HPT = High Power Turbine Introduction & Background Turboshaft engines are very similar to a turboprop engine; in fact many turboshaft engines were created by modifying existing turboprop engines to fit the needs of the rotorcraft they propel. The most common use of turboshaft engines is in scenarios where high power and reliability are required within a small envelope of requirements for size and weight. Most helicopter, marine, and auxiliary power units applications take advantage of turboshaft configurations. In fact, the turboshaft plays a workhorse role in the aviation industry as much as it is does for industrial power generation. While conventional turbine jet propulsion is achieved through thrust generated by a hot and fast exhaust stream, turboshaft engines creates shaft power that drives one or more rotors on the vehicle. -

Propulsion and Flight Controls Integration for the Blended Wing Body Aircraft

Cranfield University Naveed ur Rahman Propulsion and Flight Controls Integration for the Blended Wing Body Aircraft School of Engineering PhD Thesis Cranfield University Department of Aerospace Sciences School of Engineering PhD Thesis Academic Year 2008-09 Naveed ur Rahman Propulsion and Flight Controls Integration for the Blended Wing Body Aircraft Supervisor: Dr James F. Whidborne May 2009 c Cranfield University 2009. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. Abstract The Blended Wing Body (BWB) aircraft offers a number of aerodynamic perfor- mance advantages when compared with conventional configurations. However, while operating at low airspeeds with nominal static margins, the controls on the BWB aircraft begin to saturate and the dynamic performance gets sluggish. Augmenta- tion of aerodynamic controls with the propulsion system is therefore considered in this research. Two aspects were of interest, namely thrust vectoring (TVC) and flap blowing. An aerodynamic model for the BWB aircraft with blown flap effects was formulated using empirical and vortex lattice methods and then integrated with a three spool Trent 500 turbofan engine model. The objectives were to estimate the effect of vectored thrust and engine bleed on its performance and to ascertain the corresponding gains in aerodynamic control effectiveness. To enhance control effectiveness, both internally and external blown flaps were sim- ulated. For a full span internally blown flap (IBF) arrangement using IPC flow, the amount of bleed mass flow and consequently the achievable blowing coefficients are limited. For IBF, the pitch control effectiveness was shown to increase by 18% at low airspeeds. -

6. Chemical-Nuclear Propulsion MAE 342 2016

2/12/20 Chemical/Nuclear Propulsion Space System Design, MAE 342, Princeton University Robert Stengel • Thermal rockets • Performance parameters • Propellants and propellant storage Copyright 2016 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE342.html 1 1 Chemical (Thermal) Rockets • Liquid/Gas Propellant –Monopropellant • Cold gas • Catalytic decomposition –Bipropellant • Separate oxidizer and fuel • Hypergolic (spontaneous) • Solid Propellant ignition –Mixed oxidizer and fuel • External ignition –External ignition • Storage –Burn to completion – Ambient temperature and pressure • Hybrid Propellant – Cryogenic –Liquid oxidizer, solid fuel – Pressurized tank –Throttlable –Throttlable –Start/stop cycling –Start/stop cycling 2 2 1 2/12/20 Cold Gas Thruster (used with inert gas) Moog Divert/Attitude Thruster and Valve 3 3 Monopropellant Hydrazine Thruster Aerojet Rocketdyne • Catalytic decomposition produces thrust • Reliable • Low performance • Toxic 4 4 2 2/12/20 Bi-Propellant Rocket Motor Thrust / Motor Weight ~ 70:1 5 5 Hypergolic, Storable Liquid- Propellant Thruster Titan 2 • Spontaneous combustion • Reliable • Corrosive, toxic 6 6 3 2/12/20 Pressure-Fed and Turbopump Engine Cycles Pressure-Fed Gas-Generator Rocket Rocket Cycle Cycle, with Nozzle Cooling 7 7 Staged Combustion Engine Cycles Staged Combustion Full-Flow Staged Rocket Cycle Combustion Rocket Cycle 8 8 4 2/12/20 German V-2 Rocket Motor, Fuel Injectors, and Turbopump 9 9 Combustion Chamber Injectors 10 10 5 2/12/20 -

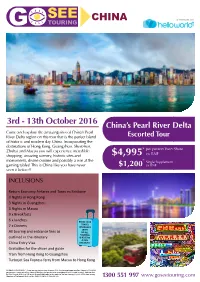

China's Pearl River Delta Escorted Tour

3rd - 13th October 2016 China’s Pearl River Delta Come and explore the amazing sites of China’s Pearl River Delta region on this tour that is the perfect blend Escorted Tour of historic and modern day China. Incorporating the destinations of Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, per person Twin Share Zhuhai and Macau you will experience incredible shopping, amazing scenery, historic sites and $4,995 ex BNE monuments, divine cuisine and possibly a win at the Single Supplement gaming tables! This is China like you have never $1,200 ex BNE seen it before!! BOOK YOUR TRAVEL INCLUSIONSINSURANCE WITH GO SEE Return EconomyTOURIN AirfaresG and Taxes ex Brisbane & RECEIVE A 25% 3 Nights in HongDISCOUNT Kong 3 Nights in Guangzhou 3 Nights in Macau 9 x Breakfasts 6 x lunches Book your Travel Insurance 7 x Dinners with Go See Touring All touring and entrance& fees receiv eas a 25% discount outlined in the itinerary China Entry Visa Gratuities for the driver and guide Train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou Turbojet Sea Express ferry from Macau to Hong Kong TERMS & CONDITIONS: * Prices are per person twin share in AUD. Single supplement applies. Deposit of $500.00 per person is required within 3 days of booking (unless by prior arrangement with Go See Touring), balance due by 03rd August 2016. For full terms & conditions refer to our website. Go See Touring Pty Ltd T/A Go See Touring Member of Helloworld QLD Lic No: 3198772 ABN: 72 122 522 276 1300 551 997 www.goseetouring.com Day 1 - Tuesday 04 October 2016 (L, D) Depart BNE 12:50AM Arrive HKG 7:35AM Welcome to Hong Kong!!!! After arrival enjoy a delicious Dim Sum lunch followed by an afternoon exploring the wonders of Kowloon. -

2. Afterburners

2. AFTERBURNERS 2.1 Introduction The simple gas turbine cycle can be designed to have good performance characteristics at a particular operating or design point. However, a particu lar engine does not have the capability of producing a good performance for large ranges of thrust, an inflexibility that can lead to problems when the flight program for a particular vehicle is considered. For example, many airplanes require a larger thrust during takeoff and acceleration than they do at a cruise condition. Thus, if the engine is sized for takeoff and has its design point at this condition, the engine will be too large at cruise. The vehicle performance will be penalized at cruise for the poor off-design point operation of the engine components and for the larger weight of the engine. Similar problems arise when supersonic cruise vehicles are considered. The afterburning gas turbine cycle was an early attempt to avoid some of these problems. Afterburners or augmentation devices were first added to aircraft gas turbine engines to increase their thrust during takeoff or brief periods of acceleration and supersonic flight. The devices make use of the fact that, in a gas turbine engine, the maximum gas temperature at the turbine inlet is limited by structural considerations to values less than half the adiabatic flame temperature at the stoichiometric fuel-air ratio. As a result, the gas leaving the turbine contains most of its original concentration of oxygen. This oxygen can be burned with additional fuel in a secondary combustion chamber located downstream of the turbine where temperature constraints are relaxed.