De Mello 1 Football, Racism, and Nationalism Time Moved in Slow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Leyenda De Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 Pie Izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney Siempre Fue Un Talento Incontro- Enero

JUGADORES GOLES 53de cabeza11 ROONEY, CON MÁS PARTIDOS Ganados 1970-90 PARTIDOS 119 1º Peter Shilton125 71 Empatados 5 2003-17 29 la leyenda de Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 pie izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney siempre fue un talento incontro- enero. "Se merece estar en los libros de 3º David Beckham pie derecho Probablemente, Rooney 115 lable. Su expulsión en los cuartos del historia del club. Estoy seguro de que ROONEY está entre los 10 mejores futbolistas Mundial de 2006 ante Portugal por su anotará muchos más", armó Sir Alex ingleses de la historia. Su carrera es trifulca con Cristiano aún retumba en las Ferguson, el técnico que le llevó al 4º Steve Gerrard2000-14 maravillosa. Islas. Jugó tres Copas del Mundo (2006, United. 114 2010 y 2014) y tres Euros (2004, 2012 y Después de ganar 14 títulos en Old Gary Lineker 2016) sin suerte. Siete goles en 21 Traord, 'Wazza' ha vuelto 13 años partidos de fases nales, 37 en 74 después a casa, al Everton, para apurar 5º Bobby Moore1962-73 Del 12 de febrero de 2003, cuando debutó encuentros ociales y 16 en 45 amistosos su carrera. Y en Goodison Park ha 108 con Inglaterra en un amistoso ante son el baje del jugador de campo con aumentado su mito anotando dos tantos Australia con 17 años y 111 días, a su más duelos y más victorias (71) de la en dos jornadas de liga inglesa que le último duelo, el 11 de noviembre de 2016 historia de Inglaterra al que han llegado disparan a los 200 goles en Premier. -

Under the Radar’ Provides a Concise Overview and Thoughtful Analysis of Critical Stories Currentlysummary Being &Overlooked

Under TheThe RadarLabour Leadership While the media landscape is preoccupiedContest by COVID-19, 2020 politics and business grinds on. ‘Under the Radar’ provides a concise overview and thoughtful analysis of critical stories currentlySummary being &overlooked. Analysis Rooney Rules Campbell had to make his start at the very bottom of the footballing pyramid with Macclesfield Town. What happened? And the disparity doesn’t end there. Kick It Out, an anti-racism campaign Lampard failed to achieve promotion but group, have criticised the Football was then awarded with the manager’s Association (FA) for failing to properly job at Chelsea, one of the biggest and implement the ‘Rooney Rule’. richest clubs in the country. Meanwhile, Campbell performed a miracle by The ‘Rooney Rule’ requires football clubs rescuing Macclesfield from seemingly to interview at least one BAME candidate inevitable relegation, but then had to walk for vacant coaching positions. But since away due to the club’s financial issues. He adopting the rule in 2016, coaching now manages Southend in the third tier demographics have hardly changed and of English football, where he cannot sign there is currently just one Premier League players due to financial restraints. manager from a BAME background. So, one privately educated footballer Raheem Sterling has provided backing with pre-existing family connections to to Kick It Out, pointing to the disparity the game has quickly risen to the top between the post-playing careers of of management, despite barely meeting Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard, expectations, while a working class son of compared to their former BAME a Jamaican factory worker has struggled teammates, Ashley Cole and Sol to get his foot in the door, even after out- Campbell. -

Described by Leading Directors As the Youth Soccer Bible, and Endorsed

Described by leading Directors as the Youth Soccer Bible, and endorsed by coaches at Manchester United, COACHING OUTSIDE THE BOX: Changing the Mindset in Youth Soccer is having a profound effect on the psyche of vast numbers of coaches and parents throughout the U.S. Paul Mairs and Richard Shaw grew up in the soccer hotbed of North West England playing against the likes of David Beckham, Paul Scholes, and Steven Gerrard. After they both progressed through the academy system of the professional and former English Premier League (EPL) club Blackpool FC, Richard went on to gain a National Championship and All-American honors playing college soccer in the U.S., and played professionally in the MISL (Major Indoor Soccer League). Paul continued his playing career in England and became heavily involved in youth development while gaining his Master’s degree and pursuing research in sport science. Furthermore, after developing young players both in Europe and the U.S. for over 15 years and travelling to various countries to research coaching methods and philosophies together they have collectively acquired valuable insight and knowledge. “Any parent whose child is playing youth soccer in the U.S. must read this book as the information is going to have a powerful impact on your child’s experiences, development, and ultimately their success in the sport. This book is an essential tool for any club, coach, or parent who is truly focusing on player development.” Manchester United Youth Academy Coach Dean Whitehouse Click the book to preview on www.amazon.com Using insightful anecdotes, personal experiences, and perspectives of numerous development experts, they passionately provide the reader with a clear and compelling breakdown of critical issues involved with youth development. -

Deschamps' Wcup

27 Sports Tuesday, July 17, 2018 Thank you heroes, You gave us everything! Media hails Croatia Croatia fly flag for the little guys ZAGREB: Croatian media yesterday hailed their team as With a population of just over four million, Croatia heroes after the small country’s historic success in reach- punched considerably above their weight to reach the ing the World Cup final where France beat them 4-2. final, going down gallantly at Moscow’s Luzhniki Stadium. “Thank you, heroes! - You gave us everything!” read the Belgium reached the semi-finals with a golden generation Sportske Novosti frontpage. “‘Vatreni’ (the “Fiery Ones” of players despite a relatively modest footballing infra- in Croatian), you are the biggest, you are our pride, your structure and will have legitimate ambitions of claiming a names will remain written in gold forever!” the newspa- first major international title at Euro 2020. At the per said. European Championship two years ago, Wales were sur- It showed a photo of captain Luka Modric who was prise semi-finalists and Iceland captured the imagination awarded the Golden Ball for the best player at the tourna- by beating England to make the last eight. With just over ment, holding a trophy, although with a sad face after the 300,000 people, Iceland followed that up by becoming defeat. “Brave hearts - You made us proud,” said Jutarnji the smallest nation to qualify for the World Cup. List daily. “Croatia celebrates you, you are our gold!” On other continents too, there are growing examples of echoed the Vecernji List. It noted that for the past month consistent challenges to the established order and particu- coach Zlatko Dalic’s team “made Croatia better”. -

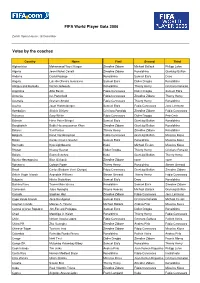

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

Case Study Football Hero Wins Fans for Pepsi

Case Study Football Hero wins fans for Pepsi PepsiCo International wanted to build on the success of its PepsiMax Club campaign. The goal was to attract male consumers aged 18-34 from new markets to its interactive digital football experience to expose them to the PepsiMax brand. Building a Social Gaming Solution Building on the momentum of the 2010 World Cup, Microsoft® Advertising and PepsiCo developed Football Hero, an innovative web experience that set the stage for football fans around the world to dive into the action and feel like a world-famous footballer. The Microsoft Advertising Global Creative Solutions team worked closely with PepsiCo International Digital Marketing and OMD International to design, build, and deploy the campaign. Microsoft Advertising promoted Client PepsiCo International the campaign in 14 global markets via editorial and media Countries UK, Spain, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Brazil, Mexico, properties such as Xbox.com, Xbox LIVE®, Hotmail®, and Romania, Greece, Poland, Argentina, Egypt, Saudi the MSN Portal. Arabia, and Ireland One key to the success of Football Hero was making the Industry CPG microsite relevant to local gamers in the 14 target Agencies OMD countries. Microsoft Advertising developed 30 versions of the microsite in 10 languages to allow PepsiCo to Objectives Engage target audience with an interactive, immersive, and fun experience showcase the individual promotions and advertising messages specifically crafted for each local market. The Target end result: A centrally controlled web experience with Audience Males 18-34 local flavor. Solutions Custom microsite, MSN, Windows Live, Xbox LIVE Results 10 million unique users One million games shared virally 10 minutes on site and games per user (average) Going from Zero to Hero The Football Hero experience offered five interactive games and featured exclusive content from international football stars such as Lionel Messi, Didier Drogba, Thierry Henry, Kaka, Frank Lampard, Fernando Torres, Andrei Arshavin, and Michael Ballack. -

Soccer in Manchester & London

Sports Travel Experience Designed Especially for Fremont Youth Soccer Club Soccer in Manchester & London August 16 - August 25, 2019 ITINERARY OVERVIEW DAY 1 DEPARTURE FROM SAN FRANCISCO DAY 2 ARRIVE MANCHESTER AREA (4 NIGHTS) DAY 3 TRAINING SESSION, MANCHESTER & PROFESSIONAL GAME DAY 4 TRAINING SESSION & MANCHESTER DAY 5 5V5 POWER LEAGUES PICK UP GAME & CHESTER DAY 6 MANCHESTER AREA - ST. GEORGES PARK - LONDON AREA (4 NIGHTS) DAY 7 LONDON DAY 8 5V5 POWER LEAGUES PICK UP GAME & LONDON DAY 9 LONDON & PROFESSIONAL GAME DAY 10 DEPARTURE FROM LONDON ITINERARY Soccer is home to England where "association rules football" was first drawn up amongst public school teams. The sport has become the passion of England where the national team, The Three Lions, won the World Cup in 1966. England also boasts the most famous soccer league in the world, The Premier League. World renowned soccer clubs Manchester United, Arsenal FC, Liverpool FC and Manchester City are just a few of the teams that call the Premier league home. Educational Tour/Visit Cultural Experience Festival/Performance/Workshop Tour Services Recreational Activity LEAP Enrichment Match/Training Session DAY 1 Friday, 16 August 2019 Relax and enjoy our scheduled flight from San Francisco to Manchester, England. * Please note that the final itinerary may be slightly different from this program. The final itinerary will be determined based on the size of the group, any adjustments that are required (such as adding additional matches), and the final schedule of the matches. (If additional matches are required, then some sightseeing content will be replaced by the additional matches needed.) DAY 2 Saturday, 17 August 2019 Our 24-hour Tour Director will meet us at the airport and remain with us until our final airport departure. -

Sepp Blatter

P 8 | FOOTBALL P 14 | BASKETBALL SoLID FoUNDATIoN GUARDED oPTImISm Construction of Al Bayt Stadium-Al Khor City, Traditional powerhouse Al Rayyan start as a proposed venue of the 2022 World Cup favourites to retain the Qatar League title, semifinal, progresses at a steady pace. but their task is easier said than done. WEDNESDAY, NovEmbER 18, 2015 | Vol X | No.42 | QR 2.00 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com Follow us on Qatar become the first team to reach the final round of World Cup Asian Zone qualification as an easy victory over Bhutan ensures Daniel Carreno’s confident wards top spot in Group C. PAGES 6-7 DSP/Fadi Al Assaad DSP/Fadi UK ...................................... £1 UAE ...............................Dh 5 Europe ............................. €2 Yemen..................75 Riyals P 10 | FOOTBALL Oman ...............200 Baisas Sudan ...................1 Pound Bahrain ..................200 Fils KSA .......................... 2 Riyals P 20 | POSTER Egypt .............................LE 2 Jordan ....................500 Fils Euro 2016 must Lebanon ..........3,000 Livre Iraq .................................... $1 SPECIAL Kuwait ....................250 Fils Palestine ......................... $1 IKER CASILLAS Morocco ......................Dh 6 Syria .............................LS 20 COLUMN go on as planned www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com | WEDNESDAY, NovEmbEr 18, 2015 3 EXCITEMENT NOW OPINION » The writer can be contacted at: JUST A TOUCH AWAY Editor-in-Chief Dr Ahmed Al Mohannadi [email protected] Managing Editor Kumar Ravi Senior Editor/Writer Aswin Abraham Senior Sports Writer N Ganesh Sports Writers Sajith B Warrier Aju George Chris Mohammad Amin-ul Islam Sarath Pookkat Positive developments for Photographers Mohan Vinod Divakaran Fadi Al Assaad Mohammed Dabboos Qatar on and off the field A K BijuRaj Graphic Designers Abhilash Chacko ATAr’S approach on the face of all the unfair higher authorities has helped us become a sporting Gopakumar K criticism hurled at it ever since winning the center par excellence. -

FA Fears That England Players Will Be Racially Abused at the Euros

THE INDEPENDENT THE INDEPENDENT 68/Sport/Football WEDNESDAY 16 MAY 2012 WEDNESDAY 16 MAY 2012 Football/Sport/69 Celtic cousins join RACE WARS ABUSE FOR ENGLISH PLAYERS With Neville in the camp, forces in hope of 12 Oct 2002, Slovakia v England investigated racist chants aimed Ashley Cole and Emile Heskey at England’s Nedum Onuoha, were targeted by Slovakian fans while Justin Hoyte was also England’s players should hosting Euro 2020 during the Euro 2004 qualifier in targeted by an opposition player Bratislava, leading to the Slovakian in the tunnel after the match. ambassador formally apologising not fall prey to indifference to the Football Association. “To 10 Sept 2008, Croatia v England By ROBIN SCOTT-ELLIOT ing patience with Turkey due to the have the whole stadium shouting Fifa fined the Croatian Federation chaos in the football there. The at you and making those gestures £15,000 after monkey chants Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Olympic clash does not help either so was frightening,” Heskey said. were aimed at Heskey in a World Ireland are set to mount a joint bid to this could be good news for Scotland, Cup qualifier in Zagreb. COMMENT host Euro 2020. Turkey and Georgia Wales and Ireland if they were to 17 Nov 2004, Spain v England are the other predicted bidders and proceed with a bid.” Shaun Wright-Phillips and Cole 10 Oct 2009, Ukraine v England JAMES as both countries have potentially Uefa are keen to encourage a Celtic were subjected to monkey chants Visiting players complained of LAWTON serious flaws as prospective hosts, the bid, especially as Georgia are expect- in a friendly held at the Bernabeu. -

Set Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1972/73 Arbeshi Reproductions George Keeling Caricatures

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Set checklist I have the complete set 1972/73 Arbeshi Reproductions George Keeling caricatures Peter Allen Orient Brian Hall Liverpool Terry Anderson Norwich City Paul Harris Orient Robert Arber Orient Ron Harris Chelsea George Armstrong Arsenal David Harvey Leeds United Alan Ball Arsenal Steve Heighway Liverpool Gordon Banks - All Stars Stoke City Ricky Heppolette Orient Geoff Barnett Arsenal Phil Hoadley Orient Phil Beal Tottenham Hotspur Pat Holland West Ham United Colin Bell - All Stars Manchester City John Hollins Chelsea Peter Bennett Orient Peter Houseman Chelsea Clyde Best West Ham United Alan Hudson Chelsea George Best - All Stars Manchester United Emlyn Hughes - All Stars Liverpool Jeff Blockley - All Stars Arsenal Emlyn Hughes Liverpool Billy Bonds West Ham United Norman Hunter Leeds United Jim Bone Norwich City Pat Jennings Tottenham Hotspur Peter Bonetti Chelsea Mick Jones Leeds United Ian Bowyer Orient Kevin Keegan Liverpool Billy Bremner Leeds United Kevin Keegan - All Stars Liverpool Max Briggs Norwich City Kevin Keelan Norwich City Terry Brisley Orient Howard Kendall - All Stars Everton Trevor Brooking West Ham United Ray Kennedy Arsenal Geoff Butler Norwich City Joe Kinnear Tottenham Hotspur Ian Callaghan Liverpool Cyril Knowles Tottenham Hotspur Clive Charles West Ham United Frank Lampard West Ham United Jack Charlton Leeds United Chris Lawler Liverpool Martin Chivers Tottenham Hotspur Alec Lindsay Liverpool Allan Clarke Leeds United Doug Livermore Norwich -

Wizards O.T. Coast Football Champions

www.soccercardindex.com Wizards of the Coast Premier League Football Champions 2001/02 checklist Arsenal □68 Mario Melchiot □136 Mark Viduka (F) □202 Claus Lundekvam □1 David Seaman □69 Slavisa Jokanovic □203 Dean Richards □2 Tony Adams (F) □70 Frank Lampard Leicester □204 Wayne Bridge □3 Ashley Cole □71 Jody Morris (F) □137 Ian Walker □205 Mark Draper □4 Lee Dixon □72 Mario Stanic □138 Callum Davidson □206 Matt Le Tissier (F) □5 Martin Keown □73 Eidur Gudjohnsen □139 Gary Rowett* □207 Chris Marsden □6 Gilles Grimaldi □74 Jimmy-Floyd Hasselbaink (F) □140 Frank Sinclair □208 Paul Murray □7 Frederik Ljunberg (F) □75 Gianfranco Zola □141 Matt Elliot □209 Matthew Oakley* □8 Ray Parlour* □142 Muzzy Izzet (F) □210 Kevin Davies □9 Robert Pires Derby □143 Matthew Jones □211 Marian Pahars (F) □10 Patrick Viera (F) □76 Andy Oakes □144 Robbie Savage (F) □212 Jo Tessem □11 Dennis Bergkamp □77 Bjorn Otto Bragstad □145 Dennis Wise □12 Thierry Henry (F) □78 Horacio Carbonari □146 Ade Akinbiyi Sunderland □13 Sylvain Wiltord □79 Danny Higginbotham □147 Arnar Gunnlaugsson □213 Thomas Sorensen □80 Chris Riggott □148 Dean Sturridge □214 Jody Craddock Aston Villa □81 Craig Burley* □215 Michael Gray (F) □14 Peter Schmeichel □82 Seth Johnson Liverpool □216 Emerson Thome (F) □15 Gareth Barry □83 Darry Powell (F) □149 Sander Westerveld □217 Stanislav Varga □16 Mark Delaney □84 Malcolm Christie (F) □150 Markus Babbel □218 Darren Williams □17 Alpay Ozalan □85 Georgi Kinkladze □151 Stephane Henchoz □219 Julio Arca □18 Alan Wright □86 Fabrizio Ravanelli □152 Sami -

Football Discipline As a Barometer of Racism in English Sport and Society, 2004-2007: Spatial Dimensions

Middle States Geographer, 2012, 44:27-35 FOOTBALL DISCIPLINE AS A BAROMETER OF RACISM IN ENGLISH SPORT AND SOCIETY, 2004-2007: SPATIAL DIMENSIONS M.T. Sullivan*1, J. Strauss*2 and D.S. Friedman*3 1Department of Geography Binghamton University Binghamton, New York 13902 2Dept. of Psychology Macalester College 1600 Grand Avenue St. Paul, MN 55105 3MacArthur High School Old Jerusalem Road Levittown, NY 11756 ABSTRACT: In 1990 Glamser demonstrated a significant difference in the disciplinary treatment of Black and White soccer players in England. The current study builds on this observation to examine the extent to which the Football Association’s antiracism programs have changed referee as well as fan behavior over the past several years. Analysis of data involving 421 players and over 10,500 matches – contested between 2003-04 and 2006-07 – indicates that a significant difference still exists in referees’ treatment of London-based Black footballers as compared with their White teammates at non-London matches (p=.004). At away matches in other London stadia, the difference was not significant (p=.200). Given the concentration of England’s Black population in the capital city, this suggests that it is fan reaction/overreaction to Black players’ fouls and dissent that unconsciously influences referee behavior. Keywords: racism, sport, home field advantage, referee discipline, match location INTRODUCTION The governing bodies of international football (FIFA) and English football (The FA or Football Association) have certainly tried to address racism in sport – a “microcosm of society.” In April of 2006, FIFA expelled five Spanish fans from a Zaragoza stadium and fined each 600 Euros for monkey chants directed towards Cameroonian striker Samuel Eto’o.