HOMEWORK SET 4 Due September 28, Monday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

Uncommon Sense in Orbit Mechanics

AAS 93-290 Uncommon Sense in Orbit Mechanics by Chauncey Uphoff Consultant - Ball Space Systems Division Boulder, Colorado Abstract: This paper is a presentation of several interesting, and sometimes valuable non- sequiturs derived from many aspects of orbital dynamics. The unifying feature of these vignettes is that they all demonstrate phenomena that are the opposite of what our "common sense" tells us. Each phenomenon is related to some application or problem solution close to or directly within the author's experience. In some of these applications, the common part of our sense comes from the fact that we grew up on t h e surface of a planet, deep in its gravity well. In other examples, our mathematical intuition is wrong because our mathematical model is incomplete or because we are accustomed to certain kinds of solutions like the ones we were taught in school. The theme of the paper is that many apparently unsolvable problems might be resolved by the process of guessing the answer and trying to work backwards to the problem. The ability to guess the right answer in the first place is a part of modern magic. A new method of ballistic transfer from Earth to inner solar system targets is presented as an example of the combination of two concepts that seem to work in reverse. Introduction Perhaps the simplest example of uncommon sense in orbit mechanics is the increase of speed of a satellite as it "decays" under the influence of drag caused by collisions with the molecules of the upper atmosphere. In everyday life, when we slow something down, we expect it to slow down, not to speed up. -

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur To cite this version: Alex Soumbatov-Gur. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution. [Research Report] Karpov institute of physical chemistry. 2019. hal-02147461 HAL Id: hal-02147461 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02147461 Submitted on 4 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur The moons are confirmed to be ejected parts of Mars’ crust. After explosive throwing out as cone-like rocks they plastically evolved with density decays and materials transformations. Their expansion evolutions were accompanied by global ruptures and small scale rock ejections with concurrent crater formations. The scenario reconciles orbital and physical parameters of the moons. It coherently explains dozens of their properties including spectra, appearances, size differences, crater locations, fracture symmetries, orbits, evolution trends, geologic activity, Phobos’ grooves, mechanism of their origin, etc. The ejective approach is also discussed in the context of observational data on near-Earth asteroids, main belt asteroids Steins, Vesta, and Mars. The approach incorporates known fission mechanism of formation of miniature asteroids, logically accounts for its outliers, and naturally explains formations of small celestial bodies of various sizes. -

Flight and Orbital Mechanics

Flight and Orbital Mechanics Lecture slides Challenge the future 1 Flight and Orbital Mechanics AE2-104, lecture hours 21-24: Interplanetary flight Ron Noomen October 25, 2012 AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 1 | Example: Galileo VEEGA trajectory Questions: • what is the purpose of this mission? • what propulsion technique(s) are used? • why this Venus- Earth-Earth sequence? • …. [NASA, 2010] AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 2 | Overview • Solar System • Hohmann transfer orbits • Synodic period • Launch, arrival dates • Fast transfer orbits • Round trip travel times • Gravity Assists AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 3 | Learning goals The student should be able to: • describe and explain the concept of an interplanetary transfer, including that of patched conics; • compute the main parameters of a Hohmann transfer between arbitrary planets (including the required ΔV); • compute the main parameters of a fast transfer between arbitrary planets (including the required ΔV); • derive the equation for the synodic period of an arbitrary pair of planets, and compute its numerical value; • derive the equations for launch and arrival epochs, for a Hohmann transfer between arbitrary planets; • derive the equations for the length of the main mission phases of a round trip mission, using Hohmann transfers; and • describe the mechanics of a Gravity Assist, and compute the changes in velocity and energy. Lecture material: • these slides (incl. footnotes) AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 4 | Introduction The Solar System (not to scale): [Aerospace -

Exploding the Ellipse Arnold Good

Exploding the Ellipse Arnold Good Mathematics Teacher, March 1999, Volume 92, Number 3, pp. 186–188 Mathematics Teacher is a publication of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). More than 200 books, videos, software, posters, and research reports are available through NCTM’S publication program. Individual members receive a 20% reduction off the list price. For more information on membership in the NCTM, please call or write: NCTM Headquarters Office 1906 Association Drive Reston, Virginia 20191-9988 Phone: (703) 620-9840 Fax: (703) 476-2970 Internet: http://www.nctm.org E-mail: [email protected] Article reprinted with permission from Mathematics Teacher, copyright May 1991 by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. All rights reserved. Arnold Good, Framingham State College, Framingham, MA 01701, is experimenting with a new approach to teaching second-year calculus that stresses sequences and series over integration techniques. eaders are advised to proceed with caution. Those with a weak heart may wish to consult a physician first. What we are about to do is explode an ellipse. This Rrisky business is not often undertaken by the professional mathematician, whose polytechnic endeavors are usually limited to encounters with administrators. Ellipses of the standard form of x2 y2 1 5 1, a2 b2 where a > b, are not suitable for exploding because they just move out of view as they explode. Hence, before the ellipse explodes, we must secure it in the neighborhood of the origin by translating the left vertex to the origin and anchoring the left focus to a point on the x-axis. -

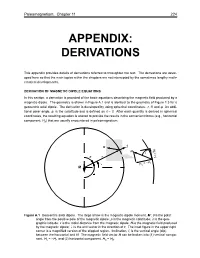

Appendix: Derivations

Paleomagnetism: Chapter 11 224 APPENDIX: DERIVATIONS This appendix provides details of derivations referred to throughout the text. The derivations are devel- oped here so that the main topics within the chapters are not interrupted by the sometimes lengthy math- ematical developments. DERIVATION OF MAGNETIC DIPOLE EQUATIONS In this section, a derivation is provided of the basic equations describing the magnetic field produced by a magnetic dipole. The geometry is shown in Figure A.1 and is identical to the geometry of Figure 1.3 for a geocentric axial dipole. The derivation is developed by using spherical coordinates: r, θ, and φ. An addi- tional polar angle, p, is the colatitude and is defined as π – θ. After each quantity is derived in spherical coordinates, the resulting equation is altered to provide the results in the convenient forms (e.g., horizontal component, Hh) that are usually encountered in paleomagnetism. H ^r H H h I = H p r = –Hr H v M Figure A.1 Geocentric axial dipole. The large arrow is the magnetic dipole moment, M ; θ is the polar angle from the positive pole of the magnetic dipole; p is the magnetic colatitude; λ is the geo- graphic latitude; r is the radial distance from the magnetic dipole; H is the magnetic field produced by the magnetic dipole; rˆ is the unit vector in the direction of r. The inset figure in the upper right corner is a magnified version of the stippled region. Inclination, I, is the vertical angle (dip) between the horizontal and H. The magnetic field vector H can be broken into (1) vertical compo- nent, Hv =–Hr, and (2) horizontal component, Hh = Hθ . -

2.3 Conic Sections: Ellipse

2.3 Conic Sections: Ellipse Ellipse: (locus definition) set of all points (x, y) in the plane such that the sum of each of the distances from F1 and F2 is d. Standard Form of an Ellipse: Horizontal Ellipse Vertical Ellipse 22 22 (xh−−) ( yk) (xh−−) ( yk) +=1 +=1 ab22 ba22 center = (hk, ) 2a = length of major axis 2b = length of minor axis c = distance from center to focus cab222=− c eccentricity e = ( 01<<e the closer to 0 the more circular) a 22 (xy+12) ( −) Ex. Graph +=1 925 Center: (−1, 2 ) Endpoints of Major Axis: (-1, 7) & ( -1, -3) Endpoints of Minor Axis: (-4, -2) & (2, 2) Foci: (-1, 6) & (-1, -2) Eccentricity: 4/5 Ex. Graph xyxy22+4224330−++= x2 + 4y2 − 2x + 24y + 33 = 0 x2 − 2x + 4y2 + 24y = −33 x2 − 2x + 4( y2 + 6y) = −33 x2 − 2x +12 + 4( y2 + 6y + 32 ) = −33+1+ 4(9) (x −1)2 + 4( y + 3)2 = 4 (x −1)2 + 4( y + 3)2 4 = 4 4 (x −1)2 ( y + 3)2 + = 1 4 1 Homework: In Exercises 1-8, graph the ellipse. Find the center, the lines that contain the major and minor axes, the vertices, the endpoints of the minor axis, the foci, and the eccentricity. x2 y2 x2 y2 1. + = 1 2. + = 1 225 16 36 49 (x − 4)2 ( y + 5)2 (x +11)2 ( y + 7)2 3. + = 1 4. + = 1 25 64 1 25 (x − 2)2 ( y − 7)2 (x +1)2 ( y + 9)2 5. + = 1 6. + = 1 14 7 16 81 (x + 8)2 ( y −1)2 (x − 6)2 ( y − 8)2 7. -

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 20: Geodesics of Schwarzschild

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 20: Geodesics of Schwarzschild Yacine Ali-Ha¨ımoud November 7, 2019 In this lecture we study geodesics in the vacuum Schwarzschild metric, at r > 2M. Last lecture we derived the following equations for timelike geodesics in the equatorial plane (θ = π=2): d' L 1 dr 2 M L2 ML2 = ; + Veff (r) = ;Veff (r) + ; (1) dτ r2 2 dτ E ≡ − r 2r2 − r3 where (E2 1)=2 can be interpreted as a kinetic + potential energy per unit mass. The radial equation can also be rewrittenE ≡ as− d2r M 3 h i = V 0 (r) = r~2 L~2r~ + 3L~2 ; r~ r=M; L~ = L=M: (2) dτ 2 − eff − r4 − ≡ CIRCULAR ORBITS AND THE ISCO We show the effective potential in Fig. 1. In contrast to the Newtonian effective potential for orbits around a central 2 2 2 3 2 mass (i.e. Veff M=r + L =2r , without the last term ML =r ), which always has a minimum at rNewt = L =M, ≡ − − the relativistic effective potential has both a maximum and a minimun for L > p12 M, an inflection point for L = p12 M, and is strictly monotonic for L < p12 M. 0 Circular orbits (with r = constant) are such that Veff (r) = 0. Solving this equation, one finds that such orbits exist only for L > p12 M. When this condition is satisfied, the radii of circular orbits are L2 p r± = 1 1 12M 2=L2 : (3) c 2M ± − The Newtonian limit is obtained for L M, in which case r+ L2=M. -

Multi-Body Trajectory Design Strategies Based on Periapsis Poincaré Maps

MULTI-BODY TRAJECTORY DESIGN STRATEGIES BASED ON PERIAPSIS POINCARÉ MAPS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Diane Elizabeth Craig Davis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii To my husband and children iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Kathleen Howell, for her support and guidance. She has been an invaluable source of knowledge and ideas throughout my studies at Purdue, and I have truly enjoyed our collaborations. She is an inspiration to me. I appreciate the insight and support from my committee members, Professor James Longuski, Professor Martin Corless, and Professor Daniel DeLaurentis. I would like to thank the members of my research group, past and present, for their friendship and collaboration, including Geoff Wawrzyniak, Chris Patterson, Lindsay Millard, Dan Grebow, Marty Ozimek, Lucia Irrgang, Masaki Kakoi, Raoul Rausch, Matt Vavrina, Todd Brown, Amanda Haapala, Cody Short, Mar Vaquero, Tom Pavlak, Wayne Schlei, Aurelie Heritier, Amanda Knutson, and Jeff Stuart. I thank my parents, David and Jeanne Craig, for their encouragement and love throughout my academic career. They have cheered me on through many years of studies. I am grateful for the love and encouragement of my husband, Jonathan. His never-ending patience and friendship have been a constant source of support. Finally, I owe thanks to the organizations that have provided the funding opportunities that have supported me through my studies, including the Clare Booth Luce Foundation, Zonta International, and Purdue University and the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics through the Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need and the Purdue Forever Fellowships. -

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

5 the Orbit of Mercury

Name: Date: 5 The Orbit of Mercury Of the five planets known since ancient times (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn), Mercury is the most difficult to see. In fact, of the 6 billion people on the planet Earth it is likely that fewer than 1,000,000 (0.0002%) have knowingly seen the planet Mercury. The reason for this is that Mercury orbits very close to the Sun, about one third of the Earth’s average distance. Therefore it is always located very near the Sun, and can only be seen for short intervals soon after sunset, or just before sunrise. It is a testament to how carefully the ancient peoples watched the sky that Mercury was known at least as far back as 3,000 BC. In Roman mythology Mercury was a son of Jupiter, and was the god of trade and commerce. He was also the messenger of the gods, being “fleet of foot”, and commonly depicted as having winged sandals. Why this god was associated with the planet Mercury is obvious: Mercury moves very quickly in its orbit around the Sun, and is only visible for a very short time during each orbit. In fact, Mercury has the shortest orbital period (“year”) of any of the planets. You will determine Mercury’s orbital period in this lab. [Note: it is very helpful for this lab exercise to review Lab #1, section 1.5.] Goals: to learn about planetary orbits • Materials: a protractor, a straight edge, a pencil and calculator • Mercury and Venus are called “inferior” planets because their orbits are interior to that of the Earth.