VICTORIOUS NARRATIVES of AFRICAN AMERICAN MALES NAVIGATING the SCHOOL-TO-PRISON NEXUS Clarice Thomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

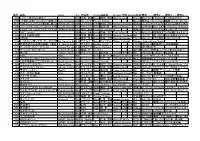

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

Page | 1 VON FREEMAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2012) Interviewee: Von

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. VON FREEMAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2012) Interviewee: Von Freeman (October 3, 1923 – August 11, 2012) Interviewer: Steve Coleman Date: May 23-24, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 110 pp. Coleman: Tuesday, May 23rd, 2000, 5:22 pm, Von Freeman oral history. My name: I’m Steve Coleman. I’ll keep this in the format that I have here. I’d like to start off with where you were born, when you were born. Freeman: Let’s see. It’s been a little problem with that age thing. Some say 1922. Some say 1923. Say 1923. Let’s make me a year younger. October the 3rd, 1923. Coleman: Why is there a problem with the age thing? Freeman: I don’t know. When I was unaware that they were writing, a lot of things said that I was born in ’22. I always thought I was born in ’23. So I asked my mother, and she said she couldn’t remember. Then at one time I had a birth certificate. It had ’22. So when I went to start traveling overseas, I put ’23 down. So it’s been wavering between ’22 and ’23. So I asked my brother Bruz. He says, “I was always two years older than you, two years your elder.” So that put me back to 1923. So I just let it stand there, for all the hysterians – historian that have written about me. -

NAETC Notes – October 16, 2012

Page 1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR + + + + + NATIVE AMERICAN EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING COUNCIL + + + + + STRATEGIC PLANNING SESSION + + + + + TUESDAY OCTOBER 16, 2012 + + + + + The Council met in Conference Rooms 2 & 3 at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2 Massachusetts Avenue, NE, Washington, DC, at 9:00 a.m., Winona Whitman, Vice Chair, presiding. PRESENT WINONA WHITMAN, Vice Chair JACOB BERNAL, Member CARLA BOWLAN, Member KIM CARROLL, Member JESSICA JAMES, Member CHRISTINE MOLLE, Member ANNE RICHARDSON, Member ELKTON RICHARDSON, Member LORENDA SANCHEZ, Member* RODNEY STAPP, Member DARRELL WALDRON, Member Neal R. Gross & Co., Inc. 202-234-4433 Page 2 DOL PARTICIPANTS EVANGELINE M. CAMPBELL, Designated Federal Officer TOYA CAPERS MIKE DELANEY YOLANDA HARRIS CRAIG LEWIS ALSO PRESENT JAMES HARDIN, LRDA BRAD HARRIS, LED ROD LOCKLEAR, LRDA *Participating via teleconference Neal R. Gross & Co., Inc. 202-234-4433 Page 3 A-G-E-N-D-A PAGE Welcome and Opening Evangeline M. Campbell, Designated Federal Officer (DFO) . .5 Managed Change - Introduction U.S. Department of Labor Professional Development and Training Office Toya Capers and Yolanda Harris, Facilitators. .6 Strategic Planning Activities Toya Capers and Yolanda Harris, Facilitators. 38 Strategic Planning Debrief Toya Capers and Yolanda Harris, Facilitators. 53 Council Strategic Planning - Closing Toya Capers and Yolanda Harris, Facilitators. 90 Neal R. Gross & Co., Inc. 202-234-4433 Page 4 1 P-R-O-C-E-E-D-I-N-G-S 2 (9:15 a.m.) 3 MS. CAMPBELL: Okay. I do believe 4 we have everyone. And we can send over to do 5 our name tags. I know normally they're always 6 here and out for you. -

MINUTES BUILDING CONSTRUCTION CODES COMMISSION February 4, 2013

MINUTES BUILDING CONSTRUCTION CODES COMMISSION February 4, 2013 MEMBERS PRESENT ALTERNATE MEMBERS PRESENT Mr. Fred Malicoat Mr. Rob Jackson Mr. Kas Carlson Mr. Eric Lidholm Mr. Brian Connell Mr. Doug Muzzy Mr. Jay Creasy Mr. Stuart Scroggs Mr. Ben Londeree Mr. John Page Mr. Mike Rose Mr. Richard Shanker Mr. Matt Young 1.) CALL TO ORDER MR. MALICOAT: Call the meeting to order. 2.) APPROVAL OF MINUTES MR. MALICOAT: I’ll entertain a motion to approve the minutes. Do I hear one? Everybody read the minutes from the last time? MR. CONNELL: I did not. UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Were they e-mailed? MR. MALICOAT: Yes, sir. MR. CONNELL: When? MR. MALICOAT: Friday. Excuse me. They were e-mailed Wednesday. UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: People didn’t get their e-mail. MR. MALICOAT: Well, I read them, so I’ll make a motion to approve the minutes. I wasn’t here, but I read them. MR. CONNELL: Well, I’ll second it then. MR. MALICOAT: Okay. MR. SHANKER: Two uninformed individuals. MR. MALICOAT: All those in favor of the minutes, aye. Opposed? (Unanimous voice vote for approval.) 3.) INTERNATIONAL BUILDING CODE REVIEW MR. MALICOAT: All right. Let’s move right into the Code Review, the IBC. I believe, Brian, you were the chairman of that committee. MR. CONNELL: Yes, sir. 1 MR. MALICOAT: So we’ll let you have the floor. MR. CONNELL: Thank you. MR. MALICOAT: And when you ask to talk to Brian, raise your hand please, and he will acknowledge you and we’ll go from there. MR. CONNELL: Does everybody or most everybody have one of these handouts (indicating)? Because in an effort to expedite this process, I’m going to suggest that we breeze through the stuff where it’s -- we considered it administrative or there were no changes, and get right to the heart of things that we wanted to bring before the BCCC and keep this thing moving. -

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin University of Tokyo, Japan Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Introduction, selection -

The Beatles and the Counterculture

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XII APRIL, 2010 THE BEATLES AND THE COUNTERCULTURE Author: Jessica Corry Faculty Sponsor: David Venturo, Department of English ABSTRACT Throughout the 1960s, the Beatles exerted enormous influence not only as a critically acclaimed and commercially successful band, but also in the realm of social and cultural change. A number of factors facilitated the Beatles‟ rise to success, including the model of 1950s rock „n‟ roll culture, their Liverpudlian roots, and a collective synergy as well as a unique ability to adapt and evolve with their era. As both agents and models of change, the Beatles played a key role in establishing three main attributes of the embryonic counterculture: the maturing sensibility of rock music, greater personal freedom as expressed by physical appearance, and experimentation with drugs. United by the goal of redefining social norms, activists, protestors, hippies, and proponents of the growing counterculture found in the Beatles an ideal representation of the sentiments of the times. Embodying the very principle of change itself, the Beatles became a major symbol of cultural transformation and the veritable leaders of the 1960s youth movement. “All you need is love, love, love is all you need” (Lennon-McCartney). Broadcast live on the international television special, “Our World,” the Beatles performed “All You Need is Love” for an unprecedented audience of hundreds of millions around the world. As confetti and balloons rained down from the studio ceiling, the Beatles, dressed in psychedelic attire and surrounded by the eccentric members of Britain‟s pop aristocracy, visually and musically embodied the communal message of the 1967 Summer of Love. -

RIAJ Yearbook 2019 1 Overview of Production of Recordings and Digital Music Sales in 2018

Statistics RIAJ YEARBOOK Trends 2019 The Recording Industry in Japan 2019 Contents Overview of Production of Recordings and Digital Music Sales in 2018 .................. 1 Statistics by Format (Unit Basis — Value Basis) .............................................................. 4 1. Total Recorded Music — Production on Unit Basis ............................................... 4 2. Total Audio Recordings — Production on Unit Basis ............................................ 4 3. Total CDs — Production on Unit Basis .................................................................... 4 4. Total Recorded Music — Production on Value Basis ............................................. 5 5. Total Audio Recordings — Production on Value Basis .......................................... 5 6. Total CDs — Production on Value Basis ................................................................. 5 7. CD Singles — Production on Unit Basis .................................................................. 6 8. 5" CD Albums — Production on Unit Basis ............................................................ 6 9. Music Videos — Production on Unit Basis ............................................................. 6 10. CD Singles — Production on Value Basis................................................................ 7 11. 5" CD Albums — Production on Value Basis.......................................................... 7 12. Music Videos — Production on Value Basis ........................................................... 7 13. Digital -

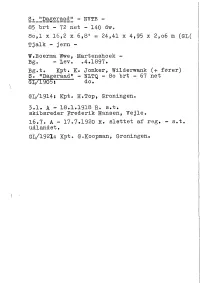

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect

PRINCE June 7, 1958 — Third Thursday in April The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect 70s 2000s 1. For You (1978) 24. The Rainbow Children (2001) 2. Prince (1979) 25. One Nite Alone... (2002) 26. Xpectation (2003) 80s 27. N.E.W.S. (2003) 3. Dirty Mind (1980) 28. Musicology (2004) 4. Controversy (1981) 29. The Chocolate Invasion (2004) 5. 1999 (1982) 30. The Slaughterhouse (2004) 6. Purple Rain (1984) 31. 3121 (2006) 7. Around the World in a Day (1985) 32. Planet Earth (2007) 8. Parade (1986) 33. Lotusflow3r (2009) 9. Sign o’ the Times (1987) 34. MPLSound (2009) 10. Lovesexy (1988) 11. Batman (1989) 10s 35. 20Ten (2010) I’VE BEEN 90s 36. Plectrumelectrum (2014) REFERRING TO 12. Graffiti Bridge (1990) 37. Art Official Age (2014) P’S SONGS AS: 13. Diamonds and Pearls (1991) 38. HITnRUN, Phase One (2015) ALBUM : SONG 14. (Love Symbol Album) (1992) 39. HITnRUN, Phase Two (2015) P 28:11 15. Come (1994) IS MY SONG OF 16. The Black Album (1994) THE MOMENT: 17. The Gold Experience (1995) “DEAR MR. MAN” 18. Chaos and Disorder (1996) 19. Emancipation (1996) 20. Crystal Ball (1998) 21. The Truth (1998) 22. The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale (1999) 23. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic (1999) DONATE TO MUSIC EDUCATION #HonorPRN PRINCE JUNE 7, 1958 — THIRD THURSDAY IN APRIL THE ULTIMATE LISTENING-RETROSPECT 051916-031617 1 1 FOR YOU You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ me away 1 For You 2. In Love (In love) April 7, 1978 Ever since I met you, baby I’m fallin’ baby, girl, what can I do? I’ve been wantin’ to lay you down I just can’t be without you But it’s so hard to get ytou Baby, when you never come I’m fallin’ in love around I’m fallin’ baby, deeper everyday Every day that you keep it away (In love) It only makes me want it more You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ Ooh baby, just say the word me away And I’ll be at your door (In love) And I’m fallin’ baby. -

View Latest Version Here. Fieldkit Open House for Educators

This transcript was exported on Mar 01, 2021 - view latest version here. Lindsay Starke: Cool. Let's give people a couple more minutes to come in, and if it's something that you are currently able to do, I would love folks to in the chat introduce yourself with your name, where you are, including the traditional denizens of the land that you're on, and we can share Native Land where you can find that if you are not already aware, as well as what you teach, and just why you're interested in FieldKit. Thanks, Jer. (silence) Jer Thorp: We'll just give everybody about another two minutes to get in here, and then we'll get started and people can always catch up with us a little later. Lindsay Starke: Yeah, so just to get some housekeeping stuff out there, we do have a pretty lovely group of folks, so lovely and large. So, if possible, if you could either type questions you have in the chat, or we're going to do a pretty hefty Q&A portion toward the end so you can ask stuff then, raise hand, all the good meeting hygiene so that we don't descend into pure chaos. (silence) All right. Beautiful. All right. I think we can go ahead and start getting things moving. Oh, more people are filtering in. That's awesome. I'll go ahead and share my screen. Jer Thorp: Yeah, and let me just say while Lindsay is talking that if anybody has any issues or questions that you don't want to put into the public feed, or if you're having tech issues or whatever, you can ping any of us with FieldKit and our names, and we'll do our best to help you out. -

'Gotta Make Your Own Heaven' Guns, Safety, and the Edge of Adulthood in New York City

'Gotta Make Your Own Heaven' Guns, Safety, and the Edge of Adulthood in New York City by Rachel Swaner, Elise White, Andrew Martinez, Anjelica Camacho, Basaime Spate, Javonte Alexander, Lysondra Webb, and Kevin Evans ‘Gotta Make Your Own Heaven’: Guns, Safety, and the Edge of Adulthood in New York City By Rachel Swaner, Elise White, Andrew Martinez, Anjelica Camacho, Basaime Spate, Javonte Alexander, Lysondra Webb, and Kevin Evans © August 2020 Center for Court Innovation 520 Eighth Avenue, 18th Floor New York, New York 10018 646.386.3100 fax 212.397.0985 www.courtinnovation.org Acknowledgements This study was supported by Award No. 2016-IJ-CX-0008 from the National Institute of Justice of the U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the Department of Justice. We would like to thank our former research assistants on this project for conducting interviews with compassion and thoughtfulness: Dereck Marmolejos, Jacques Brunvil, Gustavo Cabezas, Marcus Enfiajan, Amanda Lombardo, and William Rivera. We also thank research assistants Emily Genetta and Jona Belieu for helping with data cleaning, coding, and analysis; and Ariel Wolf for mapping participant network trees. Thanks to former Center staff members Cassandra Ramdath, Earl Thomason, Victor St. John, and Sienna Walker for their involvement in the early phases of this project. We thank Center staff Amanda Cissner, Sarah Picard, Matt Watkins, and Julian Adler for their edits to and comments on this report; and Samiha Amin Meah for designing the summary version.