Analysis of the Performance of Local Hybrid Maize Seed.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

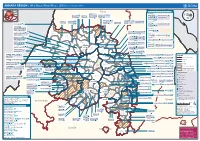

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Addis Ababa University College of Development Studies Tourism Development and Managment Programme

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Challenges in Sekela Wereda, West Gojjam, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia Submitted by: Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa A Thesis Submitted to the College of Development Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Tourism Development and Management Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2019 1 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Challenges in Sekela Wereda, West Gojjam, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia Submitted by: Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa A Thesis Submitted to the College of Development Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Tourism Development and Management Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2019 2 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa, entitled: "Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Opportunities and Challenges in Sekela Wereda". In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Tourism Development and Management complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by Examining -

The Role of Users at the Different Levels of Wash Projects

Briefing note – No. 6 The Role of Users at the Different Levels of WaSH Projects Learning and Communications in WASH in Amhara Introductio n recommendations for increasing community management of WaSH in the Amhara Region. The In Africa and other developing countries, sustainability of rural water supply is quite low with 30 to 60% of the main research document will soon be available at schemes becoming non-functional at some point after www.wateraidethiopia.org and www.bdu.edu.et. implementation (Brikké and Bredero, 2003). The lack of community participation especially in management has been recognized as one of the reasons for the low Background sustainability (Carter.1999). For example, limited Harvey and Reed (2006) explain that “community involvement of the community at all stages of water participation does not automatically lead to effective development, the lack of a modest water service fee community management, nor should it have to. and a shortage of adequate skill and capacity to Community participation is a prerequisite for maintain water resources are specific aspects of sustainability, i.e. to achieve efficiency, effectiveness, community participation that have decreased equity, and replicablity, but community management is sustainability of rural water supply in the Amhara not. The community management in rural Ethiopia is Region of Ethiopia (Mengesha et al, 2003). based on the formation of water user committees All water supply providers in Ethiopia are currently usually at each water point in order to follow up the following the principle of community participation and implementation process, to manage the WaSH scheme community management in the rural area. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

ASSESSMENT of CHALLENGES of SUSTAINABLE RURAL WATER SUPPLY: QUARIT WOREDA, AMHARA REGION a Project Paper Presented to the Facult

ASSESSMENT OF CHALLENGES OF SUSTAINABLE RURAL WATER SUPPLY: QUARIT WOREDA, AMHARA REGION A Project Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Zemenu Awoke January 2012 © 2012 Zemenu Awoke Alemeyehu ABSTRACT Sustainability of water supplies is a key challenge, both in terms of water resources and service delivery. The United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that one third of rural water supplies in sub-Saharan Africa are non- operational at any given time. Consequently, the objective of this study is to identify the main challenges to sustainable rural water supply systems by evaluating and comparing functional and non-functional systems. The study was carried out in Quarit Woreda located in West Gojjam, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. A total of 217 water supply points (169 hand-dug wells and 50 natural protected springs) were constructed in the years 2005 to 2009. Of these water points, 184 were functional and 33 were non-functional. Twelve water supply systems (six functional and six non-functional) among these systems were selected. A household survey concerning the demand responsiveness of projects, water use practices, construction quality, financial management and their level of satisfaction was conducted at 180 households. All surveyed water projects were initiated by the community and the almost all of the potential users contributed money and labor towards the construction of the water supply point. One of the main differences between the functional and non-functional system was the involvement of the local leaders. -

Debre Markos-Gondar Road

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ethiopian Roads Authority , / International Development Association # I VoL.5 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS OF THE FIVE Public Disclosure Authorized ROADS SELECTED FOR REHABILITATION AND/OR UPGRADING DEBRE MARKOS-GONDAR ROAD # J + & .~~~~~~~~i-.. v<,,. A.. Public Disclosure Authorized -r~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ - -':. a _- ..: r. -. * .. _, f_ £ *.. "''" Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report October 1997 [rJ PLANCENTERLTD Public Disclosure Authorized FYi Opastinsilta6, FIN-00520HELSINKI, FINLAND * LJ Phone+358 9 15641, Fax+358 9 145 150 EA Report for the Debre Markos-Gondar Road Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................... i ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................... iv GENERALMAP OF THE AREA ........................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................... vi I. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Location of the StudyArea. 1 1.3 Objectiveof the Study. 1 1.4 Approachand Methodologyof the Study. 2 1.5 Contentsof the Report. 3 2. POLICY,LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONALFRAMEWORK ....... 4 2.1 Policy Framework..Framewor 4 2.2 Legal Framework..Framewor 6 2.3 InstitutionalFramework. .Framewor 8 2.4 Resettlement and Compensation .12 2.5 Public Consultation 15 3. DESCRIPTIONOF THE PROPOSEDROAD PROJECT........... 16 4. BASELINEDATA ............. ........................... 18 4.1 Descriptionof the Road.18 4.2 Physical Environment nvironmt. 20 4.2.1 Climate and hydrology ................. 20 4.2.2 Physiography ............ ....... 21 4.2.3 Topography and hydrography ............ 21 4.2.4 Geology ....... ............ 21 4.2.5 Soils and geomorphology ................ 21 4.3 BiologicalEnvironment......................... 22 4.3.1 Land use and land cover .22 4.3.2 Flora .22 4.3.3 Fauna .22 4.4 Human and Social Environent .23 4.4.1 Characteristics of the population living by/alongthe road ..................... -

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1. Tigrey No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Adwa 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 2(*) Hawzen 12 3(*) Wukro 7 Per Feasibility Study 4(*) Samre 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Alamata 10 Total 55 1 Tahtay Adiyabo 8 2 Medebay Zana 10 3 Laelay Mayechew 10 4 Kola Temben 11 5 Abergele 7 Per Filed Survey by ETC 6 Ganta Afeshum 15 7 Atsbi Wenberta 9 8 Enderta 14 9(*) Hintalo Wajirat 16 10 Ofla 15 Total 115 1 Kafta Humer 5 2 Laelay Adiyabo 8 3 Tahtay Koraro 8 4 Asegede Tsimbela 10 5 Tselemti 7 6(**) Welkait 7 7(**) Tsegede 6 8 Mereb Lehe 10 9(*) Enticho 21 10(**) Werie Lehe 16 Per Filed Survey by ETC 11 Tahtay Maychew 8 12(*)(**) Naeder Adet 9 13 Degua temben 9 14 Gulomahda 11 15 Erob 10 16 Saesi Tsaedaemba 14 17 Alage 13 18 Endmehoni 9 19(**) Rayaazebo 12 20 Ahferom 15 Total 208 1/14 Tigrey D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 2. Affar No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Ayisaita 3 2 Dubti 5 Per Filed Survey by ETC 3 Chifra 2 Total 10 1(*) Mile 1 2(*) Elidar 1 3 Koneba 4 4 Berahle 4 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Amibara 5 6 Gewane 1 7 Ewa 1 8 Dewele 1 Total 18 1 Ere Bti 1 2 Abala 2 3 Megale 1 4 Dalul 4 5 Afdera 1 6 Awash Fentale 3 7 Dulecha 1 8 Bure Mudaytu 1 Per Filed Survey by ETC 9 Arboba Special Woreda 1 10 Aura 1 11 Teru 1 12 Yalo 1 13 Gulina 1 14 Telalak 1 15 Simurobi 1 Total 21 2/14 Affar D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 3. -

Prevalence of Small Ruminant Lung Worm Infection in Yilmana Densa District Northwest Ethiopia

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 27 (7): 538-543, 2019 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2019.538.543 Prevalence of Small Ruminant Lung Worm Infection in Yilmana Densa District Northwest Ethiopia Fentahun Mengie, Tsegaw Fentie and Abiyu Muluken College of Veterinary Medicine, Gondar University, Gondar, Ethiopia Abstract: A cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2017 to March 2018 to estimate the prevalence of lungworms infection and to investigate possible risk factors associated with small ruminant lungworm infections in Yilmana densa district of Amahara region, Ethiopia. Fecal samples were collected from randomly selected 384 animals (242 sheep and 142 goats) to examine first stage larvae L (1) using modified Baerman technique. The overall prevalence of lungworm infections in the study area was 53.13% (95%CI: 48.11-58.13%) in coproscopic examination. Prevalence of lungworm infection was significantly higher in goats (59.86%) than in sheep (49.17%). Three species of lungworms were identified with higher proportion of infection with Dictyocaulus filaria (62.75%) and Mulliries capillaries (23.5%). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses indicated that host related factors such as animal age, sex, body condition, respiratory illness and management were identified as potential risk factors for the occurrence of lungworms infection in small ruminants in the study area. Female animals were more likely of getting lungworm infection (OR= 2.056; p=0.001) as compared to male animals. Young age (OR=1.69; p=0.012), poor conditioned animals (OR=24.42; p=<0.001) and animals with respiratory illness were at higher risk of getting lungworm infections. -

Ethiopia, Amhara Region Infectious Disease Surveillance (Amrids) Project Completion Report

Ethiopia Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau Ethiopia, Amhara Region Infectious Disease Surveillance (AmRids) Project Completion Report February 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association 㻭㼎㼎㼞㼑㼢㼕㼍㼠㼕㼛㼚㼟㻌 AFP Acute flaccid paralysis ARHB Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention EPHI Ethiopia Public Health Institute EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization FETP Field Epidemiologist Training Programme FMoH Federal Ministry of Health HC Health Centre HDA Health Development Army HEP Health Extension Programme HEW Health Extension Worker HP Health Post IDSR Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response IHR International Health Regulation JCC Joint Coordination Committee JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency KSO Kebele Surveillance Officer NNT Neonatal Tetanus PHEM Public Health Emergency Management SNNPR Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region SOP Standard Operating Procedures TOT Training of Trainers WHO World Health Organisation Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia JICA Amhara Regional Infectious Disease Surveillance (AmRids) Project Completion Report February 2015 Contents 1㸬Background of the Project .......................................................................................... 1 2㸬Project Activity .......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Strengthening surveillance system ......................................................................... -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

Ethiopia Administrative Map As of 2013

(as of 27 March 2013) ETHIOPIA:Administrative Map R E Legend E R I T R E A North D Western \( Erob \ Tahtay Laelay National Capital Mereb Ahferom Gulomekeda Adiyabo Adiyabo Leke Central Ganta S Dalul P Afeshum Saesie Tahtay Laelay Adwa E P Tahtay Tsaedaemba Regional Capital Kafta Maychew Maychew Koraro Humera Asgede Werei Eastern A Leke Hawzen Tsimbila Medebay Koneba Zana Kelete Berahle Western Atsbi International Boundary Welkait Awelallo Naeder Tigray Wenberta Tselemti Adet Kola Degua Tsegede Temben Mekele Temben P Zone 2 Undetermined Boundary Addi Tselemt Tanqua Afdera Abergele Enderta Arekay Ab Ala Tsegede Beyeda Mirab Armacho Debark Hintalo Abergele Saharti Erebti Regional Boundary Wejirat Tach Samre Megale Bidu Armacho Dabat Janamora Alaje Lay Sahla Zonal Boundary Armacho Wegera Southern Ziquala Metema Sekota Endamehoni Raya S U D A N North Wag Azebo Chilga Yalo Amhara East Ofla Teru Woreda Boundary Gonder West Belesa Himra Kurri Gonder Dehana Dembia Belesa Zuria Gaz Alamata Zone 4 Quara Gibla Elidar Takusa I Libo Ebenat Gulina Lake Kemkem Bugna Kobo Awra Afar T Lake Tana Lasta Gidan (Ayna) Zone 1 0 50 100 200 km Alfa Ewa U Fogera North Farta Lay Semera ¹ Meket Guba Lafto Semen Gayint Wollo P O Dubti Jawi Achefer Bahir Dar East Tach Wadla Habru Chifra B G U L F O F A D E N Delanta Aysaita Creation date:27 Mar.2013 P Dera Esite Gayint I Debub Bahirdar Ambasel Dawunt Worebabu Map Doc Name:21_ADM_000_ETH_032713_A0 Achefer Zuria West Thehulederie J Dangura Simada Tenta Sources:CSA (2007 population census purpose) and Field Pawe Mecha -

A Study of Migrants from Sekela Woreda (West Gojjam) to Addis Ababa

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY Migration Decisions and Experiences: A Study of Migrants from Sekela Woreda (West Gojjam) to Addis Ababa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of Master of Arts Degree in Social Anthropology By: Fikremariam Yoseph H/Mariam ID No.GSE/1348/05 Advisor: Dr. Fekadu Adugna JULY, 2016 ADDIS ABABA ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY Migration Decisions and Experiences: A Study of Migrants from Sekela Woreda (West Gojjam) to Addis Ababa By: Fikremariam Yoseph H/Mariam Approved by Board of Examiners: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Signature _______________________________ _______________________________ Examiner Signature _______________________________ _______________________________ Examiner Signature Declaration I, Fikremariam Yoseph, declare that this thesis is my original work and has never been presented for a degree in any other university and that all sources of materials used for this thesis have been duly acknowledged. Approved by: Confirmed by: Fikremariam Yoseph Dr. Fekadu Adugna Candidate Advisor Signature: _______________________ Signature: _______________________ Date: _______________________ Date: _______________________ 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I praise God who works everything for his own ends and granting me the capability to proceed. I would also thank my advisor Dr Fikadu Adugna for his guidance and valuable feedback he provides me with. I want also to express special thanks to the respondents, who spent their valuable time and shared their knowledge and experiences with me. Last but not least, I want to thank my wife, Meskerem Shenkute, my daughter Haleluya and my family and friends for their patience and lovely support.