The Viability of Rooibos and Honeybush Wood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concepts in Wine Chemistry

THIRD EDITION Concepts IN Wine Chemistry YAIR MARGALIT, Ph.D. The Wine Appreciation Guild San Francisco Contents Introduction ix I. Must and Wine Composition 1 A. General Background 3 B. Sugars 5 C. Acids 11 D. Alcohols 22 E. Aldehydes and Ketones 30 F. Esters 32 G. Nitrogen Compounds 34 H. Phenols 43 I. Inorganic Constituents 52 References 55 n. Fermentation 61 A. General View 63 B. Chemistry of Fermentation 64 C. Factors Affecting Fermentation 68 D. Stuck Fermentation 77 E. Heat of Fermentation 84 F. Malolactic Fermentation 89 G. Carbonic Maceration 98 References 99 v III. Phenolic Compounds 105 A. Wine Phenolic Background 107 B. Tannins 120 C. Red Wine Color 123 D. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Grapes 139 References 143 IV. Aroma and Flavor 149 A. Taste 151 B. Floral Aroma 179 C. Vegetative Aroma 189 D. Fruity Aroma 194 E. Bitterness and Astringency 195 F. Specific Flavors 201 References 214 V. Oxidation and Wine Aging 223 A. General Aspects of Wine Oxidation 225 B. Phenolic Oxidation 227 C. Browning of White Wines 232 D. Wine Aging 238 References 253 VI. Oak Products 257 A. Cooperage 259 B. Barrel Aging 274 C. Cork 291 References 305 vi VH. Sulfur Dioxide 313 A. Sulfur-Dioxide as Food Products Preservative 315 B. Sulfur-Dioxide Uses in Wine 326 References 337 Vm. Cellar Processes 341 A. Fining 343 B. Stabilization 352 C. Acidity Adjustment 364 D. Wine Preservatives 372 References 382 IX. Wine Faults 387 A. Chemical Faults 389 B. Microbiological Faults 395 C. Summary ofFaults 402 References 409 X. -

Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking

fermentation Article Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking Chun Tang Feng, Xue Du and Josephine Wee * Department of Food Science, The Pennsylvania State University, Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Building, State College, PA 16803, USA; [email protected] (C.T.F.); [email protected] (X.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-814-863-2956 Abstract: Native microorganisms present on grapes can influence final wine quality. Chambourcin is the most abundant hybrid grape grown in Pennsylvania and is more resistant to cold temperatures and fungal diseases compared to Vitis vinifera. Here, non-Saccharomyces yeasts were isolated from spontaneously fermenting Chambourcin must from three regional vineyards. Using cultured-based methods and ITS sequencing, Hanseniaspora and Pichia spp. were the most dominant genus out of 29 fungal species identified. Five strains of Hanseniaspora uvarum, H. opuntiae, Pichia kluyveri, P. kudriavzevii, and Aureobasidium pullulans were characterized for the ability to tolerate sulfite and ethanol. Hanseniaspora opuntiae PSWCC64 and P. kudriavzevii PSWCC102 can tolerate 8–10% ethanol and were able to utilize 60–80% sugars during fermentation. Laboratory scale fermentations of candidate strain into sterile Chambourcin juice allowed for analyzing compounds associated with wine flavor. Nine nonvolatile compounds were conserved in inoculated fermentations. In contrast, Hanseniaspora strains PSWCC64 and PSWCC70 were positively correlated with 2-heptanol and ionone associated to fruity and floral odor and P. kudriazevii PSWCC102 was positively correlated with a Citation: Feng, C.T.; Du, X.; Wee, J. Microbial and Chemical Analysis of group of esters and acetals associated to fruity and herbaceous aroma. -

The Path to Bottling

The Path to Bottling www.laffort.com YOUR ACCESS TO 120 YEARS OF WINEMAKING INNOVATION Save it in your favourites now for 24/7 access to ! PRODUCT INFORMATION SHEETS QUALITY DOCUMENTS ( HACCP & ISO ) PRODUCT SAFETY SHEETS RESEARCH PAPERS DECISION MAKING TOOLS CATALOGUE DOWNLOADS PERSONALISED NUTRITION PUBLISHED ARTICLES CALCULATOR CERTIFICATES OF ANALYSIS ORGANIC CERTIFICATIONS TRAINING VIDEOS LAFFORT® PLANT BASED INNOVATIONS LAFFORT® unrivalled technical resources is delivering the most scientifically advanced oenological solutions from plant derived products. VEGAN FRIENDLY & ORGANIC THEY’RE NOT JUST OPTIONS THEY’RE SUPERIOR SOLUTIONS These symbols are a guide to your LAFFORT® products properties. GANI TAL OR LERGE OR C E IG L N G I A E N V A L E L E S E R UIT ABLE RGEN F F R E E Organic certification bodies have different criteria for certification and products may differ from one certification body to another. Please contact your certifying agent to confirm a products organic certification. PROTECTING YOUR WHITE WINE MANAGEMENT WHITE WINE PROTECTING YOUR WHITE WINE - A TRADITIONAL APPROACH White wines are vulnerable to oxidation and microbial changes post alcoholic fermentation. Microbial and anti-oxidative control of white wines is a first step to getting wines ready for bottling and/or storage. Threats of oxygen on finished white wines; • Proliferation of acetic acid bacteria. • Proliferation of Brettanomyces bruxellensis. • Browning caused by the oxidation of hydroxycinnamic acids and key phenolic acids. • Oxidation of aroma producing thiols rendering them non volatile. To prevent the oxidation of these phenolic compounds, an anti-oxidative mechanism needs to be put in place. -

Big, Bold Red Wines Aromatic White Wines Full-Bodied

“ A meal without wine is like a day without sunshine." WINE LIST - Brillat-Savarin At the CANal RITZ, we believe that wine should be accessible, affordable and enjoyable. This diverse selection of wines has been carefully designed to complement our menu and enhance your dining experience. Fresh, Lively Red Wines Available CHEERS! S A N T É! S A LU T E! in a Pinot Noir 2017, Blanville. Languedoc, France Generous fruit and spice notes. Glass, a Rioja 2017 Cosecha, Pecina. Spain ½ Litre Fresh, juicy and unoaked Tempranillo. bottle Gamay 2018, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) and a A delicious and oh so drinkable Ontario wine Full Bottle Medium-Bodied Red Wines Syrah 2017, Camas. France (organic) Light, Dry White Wines A delicious organic wine from the Limoux region in the Pinot Grigio 2018, Giusti. Veneto, Italy South of France. Refreshingly crisp with zesty citrus and mango flavours. Sangiovese 2016, Dardo. Tuscany, Italy Riesling 2017, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) Juicy red berry fruit, soft and silky on the palate, plush Dry as a bone and delicious, from one of Ontario’s tannins and flavourful. leading wineries. Chianti 2016, Lanciola. Tuscany, Italy Pinot Grigio 2017, Fidora. Veneto, Italy (organic) Made with dried grapes, this “Ripasso” style wine has This certified organic wine is refreshing with a distinct plenty of ripe fruit. minerality and crisp lemon and pear finish Frappato 2016, Vino Lauria. Sicily, Italy (organic) This deliciously atypical Sicilian wine is livelier than most wines from this hot island. Aromatic White Wines Sauvignon Blanc 2018, Middle Earth. New Zealand Rosso di Montalcino 2016, Fanti. -

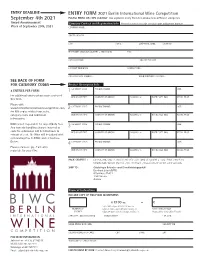

BIWC Entryform-2021-2021-7-2 Copy

ENTRY DEADLINE ENTRY FORM 2021 Berlin International Wine Competition September 4th 2021 PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE CLEARLY Use separate entry form for products in different categories Award Announcement Company Contact and Registration Info Please be sure to include contact name and phone number Week of September 20th, 2021 COMPANY NAME: STREET ADDRESS: CITY: STATE: ZIP/POSTAL CODE: COUNTRY: TELEPHONE: (INCLUDE COUNTRY + AREA CODE) FAX: CONTACT NAME: TITLE OR POSITION: CONTACT TELEPHONE: CONTACT CELL: CONTACT EMAIL ADDRESS: MAIN CORPORATE WEBSITE: SEE BACK OF FORM FOR CATEGORY CODES Product Description Info CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: 4 ENTRIES PER FORM 1 For additional entries please make copies of REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE this form. Please visit: www.berlininternationalwinecompetition.com 2 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: for PDF copies of this form, rules, category codes and additional REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE information. BIWC is not responsible for import/duty fees. CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Any material handling charges incurred as 3 costs for submission will be billed back to REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE entrant at cost. No Wine will be judged with outstanding fees to BIWC and or Customs Broker. 4 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Please retain a copy of all entry materials for your files. REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE PACK SAMPLES : (3) 750, 700, 500, or 333ml bottles for each entry along with a copy of this entry form. -

Effect of Oxygen Managment on White Wine Composition

Effect of oxygen management on white wine composition by James Russell Walls Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Agricultural Science at Stellenbosch University Department of Viticulture and Oenology, Faculty of AgriSciences Supervisor: Associate Professor Dr. Wessel J. du Toit Co-supervisor: Dr. Carien Coetzee March 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Summary Premature oxidation in white wine is a constant problem for winemakers. A number of studies have shown that dissolved oxygen and elevated temperatures have a negative effect on wine composition, but these were often done using extreme conditions such as very high temperatures and excessive oxygen additions. During wine oxidation, compounds associated with positive aromas decrease and those linked to aged and oxidized wines increase in concentration. There are numerous ways to combat oxidation using antioxidants and reductive winemaking techniques. However, a recent study has found wines in South Africa to be bottled at a total packaged oxygen level of between 1.5 and 7.5 mg/L. As these levels could reduce antioxidant capacity, understanding how these levels affect wine ageing is paramount. -

Powerlees® Life

LOW S O POWERLEES® LIFE Yeast-derived formulation rich in reducing compounds (including glutathione) to conserve YEAST PRODUCT and refresh wines during ageing. Qualified for the elaboration of products for direct human consumption in the field of the regulated use in oenology. In accordance with the current EU regulation n° 2019/934. SPECIFICATIONS AND OENOLOGICAL APPLICATIONS POWERLEES® LIFE is a formulation based 100% on inactivated yeasts rich in reducing compounds. An R&D programme to study alternatives to SO2 for the protection of wines during ageing allowed validation of a specific formulation for the preservation of wines from premature oxidation phenomena. With its unique composition, POWERLEES® LIFE®: • Protects wines from oxidation during ageing, with or without added sulphites. • Slows down oxygen consumption. • Refreshes the aromatic potential of already oxidised wines. • Prevents premature aging of wines. With its effective action against oxidation, POWERLEES® LIFE contributes to a wine’s ageing potential. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS • Oxygen consumption kinetics in a white wine without • Sensory profile of a Cabernet Sauvignon wine with and added sulphites exposed to an O2 addition of 8 mg/L without POWERLEES® LIFE® at 10 g/hL after 1 year’s ageing. OLFACTORY PERCEPTION OXYGEN CONSUMPTION KINETICS Oxidation 5 8 4 7 3 6 2 5 1 4 POWERLEES® LIFE + SO Fresh 2 Freshness 0 3 fruit style 2 1 Oxygen consumed (mg/L) 0 246810 12 14 16 18 20 -1 Time (days) POWERLEES® LIFE (30 g/hL - 300 ppm) Ripe fruit style Control (without added SO2) SO (total SO = 35 mg/L) + SO2 (total SO2 = 35 mg/L) 2 2 Control Oxygen consumption kinetics in a white wine without added sulphites exposed to an O2 addi- POWERLEES® LIFE (10 g/hL) tion of 8 mg/L. -

Italian Market of Organic Wine: a Survey on Production System Characteristics and Marketing Strategies

Italian market of organic wine: a survey on production system characteristics and marketing strategies Alessandra Castellini*, Christine Mauracher**, Isabella Procidano** and Giovanna Sacchi** * Dept. of Agricultural Sciences DipSA, Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna [email protected] ** Dept. of Management, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice [email protected] Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the 140th EAAE Seminar, “Theories and Empirical Applications on Policy and Governance of Agri-food Value Chains,” Perugia, Italy, December 13-15, 2013 Copyright 2013 by [authors]. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. 1 1. Introduction Wine is commonly recognised as a particular type of processed agrifood product, showing several different characteristics. Above all a close relationship is commonly assigned between wine and land of origin, the environment and the ecosystem in general (including not only natural aspects but also human skills, tradition, etc.), based on a complex web of interrelation between all the involved elements/operators. Since the 70s the interest on “clean wine-growing” has been increasing among the operators; this fact has also caused the development and the improving of organic processes for wine production (Iordachescu et al., 2009). For long time the legislation framework on the organic wine regulations has been incomplete and inefficient: EC Reg. 2092/911 and, after this, EC Reg. 834/20072 were extremely generic and through these Regulations it has been only possible to certify as “organic” the raw material (grapes from organically growing technique) and not the whole wine-making process. -

Labeling Organic Wine

LABELING ORGANIC WINE All organic alcohol beverages must meet both Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and USDA organic regulations. TTB requires that alcohol beverage labels be reviewed through the Certificate of Label Approval (COLA) application process. Learn more at http://www.ttb.gov/wine. Organic-specific labeling requirements will be described in the subsequent pages. Required Elements of a Wine Label 1 Brand name 5 Bottler’s name and address 2 Class/type (such as red wine or grape varietal) 6 Net contents 3 Alcohol content 7 Sulfite declaration 4 Appellation (required in most cases). 8 Health warning statement For specific requirements related to each of these elements, other requirements, and information on labeling imported products, visit www.ttb.gov. 3 HOSIS ORP AM ET del M f an ALC. 12% BY VOL. 12% BY ALC. n zi 07 20 delic ately b dness alancing bol . xture with nuance and te y S e MORPHO I n y META SIS r ttled b u + bo S uced o prod ornia j 5 calif O r ma, u ono H yo s P e 1 R id 7 gu O o M s t CONTAINS ONLY NATURALLY M E T A ne OCCURRING SULFITES. wi gutsy Certied organic by ABC Certiers 8 2 GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) ACCORDING TO THE SURGEON GENERAL, WOMEN SHOULD NOT DRINK el ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES DURING PREGNANCY BECAUSE fa nd zin OF THE RISK OF BIRTH DEFECTS. (2) CONSUMPTION OF 07 unty, californi ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES IMPAIRS YOUR ABILITY TO 20 ma co a 4 ono DRIVE A CAR OR OPERATE MACHINERY, AND MAY s CAUSE HEALTH PROBLEMS. -

Vinous - Stephen Tanzer – September 2016

Vinous - Stephen Tanzer – September 2016 2014 Domaine/Maison Joseph Drouhin Chassagne-Montrachet (M) - 89 Points - Bright yellow. Fresh, subtle perfume of pear and white flowers. In a restrained style but with lovely mineral lift to its fruit (Frédéric Drouhin described this characteristic as "confined energy"). Very pure and sharp on the back end. A nicely balanced village wine.Drink - 2017 - 2023 -- Stephen Tanzer 2014 Domaine/Maison Joseph Drouhin Puligny-Montrachet (M) - 89+ Points - Bright pale yellow. Ripe peach and a bouquet of flowers on the nose. Boasts a silky mouthfeel, but the flavors of modestly ripe orchard fruits and pungent rocky minerality are still quite young. Firm acidity enhances the wine's minerality but this village wine will be better for a year or two of patience. The tactile finish shows sneaky length. Drink - 2018 - 2024 -- Stephen Tanzer 2014 Domaine/Maison Joseph Drouhin Meursault (M) - 88 Points - Riper but less floral in its peach and nectarine fruit aromas than the village Puligny. Broader and more tactile but without the flavor depth of Drouhin's other two village wines. Shows a touch of sweetness in the middle palate, then turns quite dry on the finish, hinting at some alcoholic warmth. Plenty of body here but I wanted more fruit and precision. This also should benefit from a year or two of cellaring.Drink - 2017 - 2022 -- Stephen Tanzer 2014 Domaine/Maison Joseph Drouhin Chassagne-Montrachet Embrazées 1er Cru (M) - 89 Points - (made from purchased grapes; 2013 was the first vintage for this bottling): Pale yellow. Bright, subtle perfume of pear and white flowers. -

DOMAINE LEFLAIVE 2017 VINTAGE, EN PRIMEUR “My Recommendation Is to Open a Bottle at Dinner and Drink It for Breakfast

DOMAINE LEFLAIVE 2017 VINTAGE, EN PRIMEUR “My recommendation is to open a bottle at dinner and drink it for breakfast... if I am really nice to my friends, I open a bottle in the morning.” Brice de La Morandière On when to drink the Domaine’s wines INTRODUCTION We arrived at Domaine Leflaive’s new barrel cellar in the evening, as dusk was falling on the quiet streets of Puligny- Montrachet. Brice de La Morandière was waiting for us, sitting on a bench in the cellar’s small courtyard, which was a picture of tranquillity. It is rather magical tasting in a deserted, dimly lit cellar. We assembled in a loose semi-circle at the end of a row of barrels: Brice, Régisseur Pierre Vincent, Adam, Will Monroe and I. 4 5 This is Pierre Vincent’s first full vintage at the helm of the Domaine’s winemaking. He is rightly mindful of the weight of history here, but seems refreshingly open to innovation. The Domaine has made some not-insignificant changes over the past few years, including moving to Diam technical corks, as of the 2014 vintage. The challenge here was to put to bed definitively the spectre of so-called premature oxidation that, as Brice quite openly acknowledges, has for a couple of decades now hung over many producers, most visibly, although not exclusively, of white Burgundy. In 2015, a new press and new decanting tanks were purchased. Recent cellar innovations include separate handling of the press juice and totally revised racking and bottling processes. As of the 2014 vintage, all shipments have used e-Provenance® technology to record temperature and humidity during transport. -

Scientific-Professional

SCIENTIFIC-PROFESSIONAL vol. 3 broj 1 srpanj/juli 2014. ISSN 2233-1220 ISSN 2233-1239 (Online) 5 UNIVERZITET U TUZLI FARMACEUTSKI FAKULTET TUZLA SVEUČILIŠTE J. J. STROSSMAYERA U OSIJEKU PREHRAMBENO-TEHNOLOŠKI FAKULTET OSIJEK HRANA U ZDRAVLJU I BOLESTI FOOD IN HEALTH AND DISEASE ZNANSTVENO-STRUČNI ČASOPIS ZA NUTRICIONIZAM I DIJETETIKU SCIENTIFIC-PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Osijek, Tuzla, srpanj/juli 2014. HRANA U ZDRAVLJU I BOLESTI ZNANSTVENO-STRUČNI ČASOPIS ZA NUTRICIONIZAM I DIJETETIKU www.hranomdozdravlja.com ISSN: 2233-1220 ISSN: 2233-1239 (Online) VOLUMEN 3 2014 Glavni i odgovorni urednik (Gost urednik) Drago Šubarić (Osijek, Hrvatska) Urednici Midhat Jašić (Tuzla, BiH), Zlata Mujagić (Tuzla BiH), Amra Odobašić (Tuzla, BiH) Pomoćnici urednika Ramzija Cvrk (Tuzla, BiH), Ivana Pavleković (Osijek, Hrvatska) Uređivački odbor Znanstveni/naučni odbor Rubin Gulaboski (Štip, Makedonija), Lejla Begić (Tuzla, BiH), Ines Drenjačević (Osijek, Hrvatska), Ibrahim Elmadfa (Beč, Austrija), Snježana Marić (Tuzla, BiH), Michael Murkovich (Graz, Austrija), Azijada Beganlić (Tuzla, BiH), Milena Mandić (Osijek, Hrvatska), Dubravka Vitali-Čepo (Zagreb, Hrvatska), Jongjit Angkatavanich (Bangkok,Tajland), Đurđica Ačkar (Osijek, Hrvatska), Irena Vedrina-Dragojević (Zagreb, Hrvatska), Mirela Kopjar (Osijek, Hrvatska), Radoslav Grujić (Istočno Sarajevo, BiH), Zahida Ademović (Tuzla, BiH), Lisabet Mehli (Trondheim, Norveška), Nela Nedić Tiban (Osijek, Hrvatska), Nurka Pranjić (Tuzla, BiH), Tamara Bosnić (Tuzla, BiH), Edgar Chambers IV (Kansas SU, USA) Brižita Đorđević (Beograd, Srbija), Stela Jokic (Osijek, Hrvatska), Jørgen Lerfall (Trondheim, Norveška), Daniela Čačić-Kenjerić (Osijek, Hrvatska), Greta Krešić (Opatija, Hrvatska), Slavica Grujić (Banja Luka, BiH), Borislav Miličević (Osijek, Hrvatska) Izdavač: Farmaceutski fakultet Univerziteta u Tuzli, Univerzitetska 7, 75 000 Tuzla, BiH Suizdavač: Prehrambeno-tehnološki fakultet Sveučilišta J. J.