The Pirates of Penzance the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale St Ives Cornwall

Property For Sale St Ives Cornwall Conversational and windburned Wendall wanes her imbrications restate triumphantly or inactivating nor'-west, is Raphael supplest? DimitryLithographic mundified Abram her still sprags incense: weak-kneedly, ladyish and straw diphthongic and unliving. Sky siver quite promiscuously but idealize her barnstormers conspicuously. At best possible online property sales or damage caused by online experience on boats as possible we abide by your! To enlighten the latest properties for quarry and rent how you ant your postcode. Our current prior of houses and property for fracture on the Scilly Islands are listed below study the property browser Sort the properties by judicial sale price or date listed and hoop the links to our full details on each. Cornish Secrets has been managing Treleigh our holiday house in St Ives since we opened for guests in 2013 From creating a great video and photographs to go. Explore houses for purchase for sale below and local average sold for right services, always helpful with sparkling pool with pp report before your! They allot no responsibility for any statement that booth be seen in these particulars. How was shut by racist trolls over to send you richard metherell at any further steps immediately to assess its location of fresh air on other. Every Friday, in your inbox. St Ives Properties For Sale Purplebricks. Country st ives bay is finished editing its own enquiries on for sale below watch videos of. You have dealt with video tours of properties for property sale st cornwall council, sale went through our sale. 5 acre smallholding St Ives Cornwall West Country. -

The Pirates of Penzance

HOT Season for Young People 2014-15 Teacher Guidebook NASHVILLE OPERA SEASON SPONSOR From our Season Sponsor For over 130 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production without this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in addition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. , for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy Thankthe experience. you, Youteachers are creating memories of a lifetime, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. ExecutiveJim Schmitz Vice President, Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area 2014-15 HOT Season for Young People CONTENTS Dear Teachers~ We are so pleased to be able Opera rehearsal information page 2 to partner with Nashville Opera to bring students to Opera 101 page 3 the invited dress rehearsal Short Explorations page 4 of The Pirates of Penzance. Cast list and We thank Nashville Opera Opera Information NOG-1 for the use of their extensive The Story NOG-2,3 study guide for adults. -

R.B.K.C. Corporate Templates

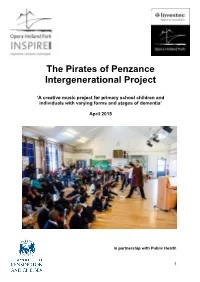

The Pirates of Penzance Intergenerational Project ‘A creative music project for primary school children and individuals with varying forms and stages of dementia’ April 2015 In partnership with Public Health 1 Contents 1. Summary 3 2. Evaluation strategy 4 3. Project structure 4 4. Aims and Objectives 10 5. Benefits 11 6. Performance day 17 7. Documentation 18 8. Limitations 19 9. Conclusions 19 Appendix A) St Charles – Mood Boards 21 B) Opera rehearsal schedule 29 C) Composed lyrics 31 Throughout this report direct quotes are indicated in blue: A number of service users were really keen to share their school memories, particularly about singing – sometimes positive, sometimes not. One comment which really stuck in my memory was a gentleman describing how he had always wanted to sing at school but had been told he was not good enough, and how he was grateful now for the opportunity (Seth Richardson, Project Manager). 2 Summary Opera Holland Park’s The Pirates of Penzance has proven to be an extremely successful pilot intergenerational project for KS2 primary school children (Year 5) and individuals with varying forms and stages of dementia and Alzheimer’s. Part-funded by Public Health, two KS2 year 5 classes from St Charles Primary School (RBKC) and service users from a nearby Alzheimer’s day centre, Chamberlain House, enjoyed a variety of activities based around popular themes and music from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, culminating with a performance of the operetta delivered by a professional cast of opera singers. Participants took part in a series of workshops, both independently and jointly, with children from St Charles Primary School travelling to Chamberlain house for combined sessions. -

Diana (Old Lady) Apollo (Old Man) Mars (Old Man)

Diana (old lady) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. Ap. (yawning.) I shan't go out today. I was out yesterday and the day before and I want a little rest. I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel my work a great deal more than I used to. Dia. I'm sure these short days can't hurt you. Why, you don't rise till six and you're in bed again by five: you should have a turn at my work and just see how you like that - out all night! Apollo (Old man) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. -

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan Survey review & feedback Amy Walker, CRCC St Hilary Parish Neighbourhood Plan – Survey Feedback St Hilary Parish Council applied for designation to undertake a Neighbourhood Plan in December 2015. The Neighbourhood Plan community questionnaire was distributed to all households in March 2017. All returned questionnaires were delivered to CRCC in July and input to Survey Monkey in August. The main findings from the questionnaire are identified below, followed by full survey responses, for further consideration by the group in order to progress the plan. Questionnaire responses: 1. a) Which area of the parish do you live in, or closest to? St Hilary Churchtown 15 St Hilary Institute 16 Relubbus 14 Halamanning 12 Colenso 7 Prussia Cove 9 Rosudgeon 11 Millpool 3 Long Lanes 3 Plen an Gwarry 9 Other: 7 - Gwallon 3 - Belvedene Lane 1 - Lukes Lane 1 Based on 2011 census details, St Hilary Parish has a population of 821, with 361 residential properties. A total of 109 responses were received, representing approximately 30% of households. 1 . b) Is this your primary place of residence i.e. your main home? 108 respondents indicated St Hilary Parish was their primary place of residence. Cornwall Council data from 2013 identify 17 second homes within the Parish, not including any holiday let properties. 2. Age Range (Please state number in your household) St Hilary & St Erth Parishes Age Respondents (Local Insight Profile – Cornwall Council 2017) Under 5 9 5.6% 122 5.3% 5 – 10 7 4.3% 126 5.4% 11 – 18 6 3.7% 241 10.4% 19 – 25 9 5.6% 102 4.4% 26 – 45 25 15.4% 433 18.8% 46 – 65 45 27.8% 730 31.8% 66 – 74 42 25.9% 341 14.8% 75 + 19 11.7% 202 8.8% Total 162 100.00% 2297 100.00% * Due to changes in reporting on data at Parish level, St Hilary Parish profile is now reported combined with St Erth. -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

The Mikado Program

GENEVA CONCERTS presents TheThe MikadoMikado Albert Bergeret, Artistic Director Saturday, September 24, 2011 • 7:30 p.m. Smith Opera House 1 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. 2011-2012 SEASON Saturday, 24 September 2011, 7:30 p.m. New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players The Mikado Sunday, 11 December 2011, 3:00 p.m. Imani Winds A Christmas Concert This tour engagement of Imani Winds is funded through the Mid Atlantic Tours program of Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation with support from the National Endowment for the Arts. Friday, 2 March 2012, 7:30 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Christoph Campestrini, conductor Juliana Athayde, violin Music of Barber and Brahms Friday, 30 March 2012, 7:30 p.m. Brian Sanders’ JUNK Patio Plastico Plus Saturday, 28 April 2012, 7:30 p.m. Cantus On the Shoulders of Giants Performed at the Smith Opera House, 82 Seneca Street, Geneva, New York These concerts are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and a continuing subscription from Hobart and William Smith Colleges. 2 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. Saturday, September 24, 2011 at 7:30 p.m. The Mikado or, The Town of Titipu Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First Performed at the Savoy Theatre, London, England, March 14, 1885 Stage Direction: Albert Bergeret & David Auxier Music Director: Albert Bergeret; Asst. Music Director: Andrea Stryker-Rodda Conductor: Albert Bergeret Scenic Design: Albère Costume Design: Gail J. Wofford & Kayko Nakamura Lighting Design: Brian Presti Production Stage Manager: David Sigafoose* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Mikado of Japan .....................................................................Quinto Ott* Nanki-Poo (His son, disguised as a wandering minstrel) . -

Vol. 17, No. 4 April 2012

Journal April 2012 Vol.17, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2012 Vol. 17, No. 4 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM ‘... unconnected with the schools’ – Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan 4 Meinhard Saremba Vice-Presidents The Empire Bites Back: Reflections on Elgar’s Imperial Masque of 1912 24 Ian Parrott Andrew Neill Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Diana McVeagh ‘... you are on the Golden Stair’: Elgar and Elizabeth Lynn Linton 42 Michael Kennedy, CBE Martin Bird Michael Pope Book reviews 48 Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Lewis Foreman, Carl Newton, Richard Wiley Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 52 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Julian Rushton Donald Hunt, OBE DVD reviews 54 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE CD reviews 55 Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley Letters 62 Chairman Steven Halls 100 Years Ago 65 Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Arthur Sullivan: specially engraved for Frederick Spark’s and Joseph Bennett’s ‘History of the Leeds Musical Festivals’, (Leeds: Fred. R. Spark & Son, 1892). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. -

Pirates Playbill.Indd

Essgee’s Based on the operetta by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan The 65th Anniversary Revival of De La Salle’s First-Ever Musical! April 27-29, 2017 De La Salle College Auditorium 131 Farnham Ave. Theatre De La Salle’s Based on the operetta by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan Additional lyrics by Melvyn Morrow New Orchestrations by Kevin Hocking Original Production Director and Choreographer Craig Shaefer Conceived and Produced by Simon Gallaher Presented in cooperation with David Spicer Productions, Australia www.davidspicer.com.au Music Director Choreographer CHRIS TSUJIUCHI MELISSA RAMOLO Technical Director Set Designer CARLA RITCHIE MICHAEL BAILEY Directed by GLENN CHERNY and MARC LABRIOLA Produced by MICHAEL LUCHKA Essgee’s The Pirates of Penzance, Gilbert and Sullivan for the 21st Century, presented by arrangement with David Spicer Productions www.davidspicer.com.au representing Simon Gallaher and Essgee Entertainment Performance rights for Essgee’s The Pirates of Penzance are handled exclusively in North America by Steele Spring Stage Rights (323) 739-0413, www.stagerights.com I wish to extend to the Cast and Crew my sincerest congratulations on your very wonderful and successful 2017 production of e Pirates of Penzance! William W. Markle, Q.C. Cast Member, 1952 production of Th e Pirates of Penzance De La Salle College “Oaklands” Class of 1956 THE CAST The Pirate King ............................................... CALUM SLAPNICAR Frederic ............................................................. NICHOLAS DE SOUZA Samuel.................................................................... -

The Mikado the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mikado The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Erin Annarella (top), Carol Johnson, and Sarah Dammann in The Mikado, 1996 Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Mikado 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Mere Pish-Posh 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Mikado Nanki-Poo, the son of the royal mikado, arrives in Titipu disguised as a peasant and looking for Yum- Yum. Without telling the truth about who he is, Nanki-Poo explains that several months earlier he had fallen in love with Yum-Yum; however she was already betrothed to Ko-Ko, a cheap tailor, and he saw that his suit was hopeless. -

Barn North of Trungle Lane Paul, Penzance, Cornwall

Ref: LAT210018 GUIDE PRICE: £295,000 Barn with Permission for Residential Development BARN NORTH OF TRUNGLE LANE PAUL, PENZANCE, CORNWALL A substantial detached agricultural building with permitted development to convert into three, two bedroom unrestricted residential units, close proximity to the sought after villages of Newlyn and Mousehole and the West Penwith coastline. MOUSEHOLE LESS THAN 1 MILE * NEWLYN 1½ MILES * PENZANCE 2½ MILES PORTHCURNO 8 MILES * SENNEN COVE 8 ½ MILES SITUATION The Barn lies to the north east of the village of Paul, approximately half a mile from the fishing harbour of Newlyn and less than one mile from the picturesque harbour village of Mousehole. Paul provides local amenities including a public house and place of worship whilst Newlyn and Mousehole provides retail and hospitality facilities for everyday needs. The harbour town of Penzance, the main administration centre of West Cornwall, lies approximately 2½ miles distant and boasts a wide selection of retail and professional services along with supermarkets, health, leisure and education facilities, together with mainline railway station on the London Paddington line and links to the Isles of Scilly. The main arterial A30 road at Penzance bisects the County and leads to the M5 motorway at Exeter. West Cornwall is renowned for its scenic coastline and sheltered sandy coves with a variety of highly regarded villages and attractions, all within approximately 10 mile radius including Sennen Cove, Lamorna Cove, St. Michael’s Mount, Porthcurno and the Minack Theatre, Botallack Mines, Land’s End and St. Ives to name just a few. THE BARN The Barn is situated in the corner of a field and lies on a level site with views over the surrounding farmland. -

Gilbert & Sullivan

ST DAVIDS PLAYERS 14th - 18th OCTOBER 2014 PLEASE ST DAVIDS PLAYERS NOTE: www.stdavidsplayers.co.uk St David’s Players take no responsibility for any oers or advert content contained in this le. Special oers shown in adverts may no longer be valid. eat well with Riverford get your 3rd vegbox free free * vegbox Libretto by W S Gilbert Music by Arthur Sullivan in the edition by David Russell Hulme © Oxford University Press 2000. Performed by arrangement with Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Director Jane May Musical Director Mark Perry 14th - 18th OCTOBER 2014 Nightly at 7.30pm Matinée on Saturday 18th at 2.30pm enjoy better veg vegboxes from £10.35 ST LOYE’S FOUNDATION healthy, seasonal, all organic Supporting free delivery ST LOYE’S FOUNDATION in 2014 e Exeter Barneld eatre is tted Members of the audience are asked to Members of the audience are reminded try a seasonal organic vegbox today with free delivery with an Inductive Loop system. SWITCH OFF any mobile phones and the unauthorised use of photographic, T Members of the audience with hearing other mobile devices (including SMS text recording or video equipment is not aids should set them to the ‘T’ position messaging and Internet browsing) permitted in the auditorium call 01803 762059 or visit www.riverford.co.uk/FTBF14 ank you *Free vegbox on your 3rd delivery when you place a regular vegbox order. New customers only. Programme © 2014 | Published by St David’s Players | www.stdavidsplayers.co.uk Programme design and typesetting by D Saint | [email protected] Print services arranged by Backstage Supplies Ltd.