How Singers Fall in Love with Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUDI SILVANO Vocalist, Composer, Lyricist

Website: judisilvano.com Booking: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel: 914 213-2992 JUDI SILVANO Vocalist, Composer, Lyricist JUDI SILVANO’S WOMEN’S WORK By Lynn Jordan, March 2009 Judi Silvano is a traditional Jazz singer, whose release “Woman’s Work” showcases her bright voice against a simple backdrop of piano, drums and bass in an intimate live performance. Rosemary Clooney, Peggy Lee with a pinch of Ella Fitzgerald are good points of reference for her vocal style. Silvano is not afraid to be playful and light on such songs as “Not To Worry” and “New Dance” where she scats convincingly, and she can also handle a song with more depth such as “Inside A Silent Tear” and the lovely “Why Do I Still Dream of You”, which is the standout track and her best vocal performance. The backing band’s musicianship is excellent, and they exercise restraint where other musicians may have gone overboard with solos. This CD is pleasant listen, and perfect for those who can appreciate a singer with a clean, unfussy voice that is not afraid to take some chances for her craft. Judi Silvano: Women’s Work - 4 STARS DOWN BEAT MAGAZINE Caught live at New York’s Sweet Rhythm in March 2006, JSilvano gives a masterful performance. The album title nods not only to the bold, vibrant all-female ensemble, but to the repertoire, which was penned exclusively by women. Far more than a concept album, Women’s Work finds the singer at the peak of her creative game. Silvano displays a firm knowledge of jazz history and vocal technique, subtly coloring the songs with a well-placed shere, a cheery squeak there. -

CHAN 10411 Booklet.Indd

CHAN 10411 Words and Music Katie Vandyck 1 It might as well be spring 3:12 Words: Oscar Hammerstein II Music: Richard Rodgers 2 Don’t sleep in the subway 3:18 Words: Tony Hatch Music: Jackie Trent 3 Get rid of Monday 2:37 Words: Johnny Burke Music: Jimmy van Heusen 4 Someone to watch over me 4:16 Words: Ira Gershwin Music: George Gershwin 5 Angel eyes 4:10 Words: Tom Adair Music: Matt Dennis Richard Rodney Bennett 3 6 Spring can really hang you up the most 5:01 11 On second thought 3:56 Words: Fran Landesman Words: Carolyn Leigh Music: Tommy Wolf Music: Cy Coleman 7 Let me down easy 4:02 12 Early to bed 3:07 Words: Carolyn Leigh Words: Franklin Underwood Music: Cy Coleman Music: Richard Rodney Bennett 8 I won’t dance 2:57 13 Wake up, chill’un, wake up 3:45 Words: Dorothy Fields Words: Jo Trent Music: Jerome Kern Music: Willard Robison 9 Killing time 3:00 14 Goodbye for now 3:27 Words: Carolyn Leigh Words: Charles Hart Music: Jule Styne Music: Richard Rodney Bennett 10 How long has this been going on? 4:23 15 Words and Music 2:32 Words: Ira Gershwin Words: Richard Rodney Bennett Music: George Gershwin Music: Richard Rodney Bennett TT 53:52 Richard Rodney Bennett vocals and piano 4 5 and Jackie Trent), to which Richard was Orchestra at the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the Richard Rodney Bennett: Words and Music introduced by the late great British jazz BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus at the pianist Pat Smythe. -

Cash Box March 6, 1993 8

CASH BOX MARCH 6, 1993 8 TALENT RE¥8BW TALENT REVIEW Blossom Dearie Suzanne Vega By Robert Adds By Hilarie Grey McCABE’S, SANTA MONICA, CA—Cute. Mature. Off-center. In- dividually, these words describe legions of recording artists. But string them together and the field narrows to the sin- gularly magnificent Blos- som Dearie. Her "cute" is not the cultivated variety, but the genetically pre-deter- mined kind. Thank her parents for the perky visage on her just-reissued Verve album Once Upon A Summertime. Her model- next-door look is the real thing, and not just another example of the countless blondes who appeared on '50s album covers as mute stand-ins for the less-than- photogenic Hugo Winter- THE WILTERN THEATRE, LOS ANGELES, CA—On her latest halters of the era. album, 99.9 °F, Suzanne Vega (A&M Records) breaks striking new The cuteness of ground by surrounding and infusing her gentle acoustic-based sound Blossom's voice and ap- with a full complement of unusual rhythms, textures and noises. These pearance have both defied bold strokes, which vary from "industrial" bangs and crashes to brassy the chronological challenge of four intervening decades. As if to provide calliope-like keyboard settings, combined with Vega's keenly observa- scientific proof of that observation, her current songbag still includes tional lyrics and deadpan delivery, made for a superbly executed "Everything I've Got (Belongs To You)," the sweetly menacing Rodgers evening of musical contrasts for the Wiltem audience. & Hart song from her very first Verve album Blossom Dearie (also From the spare, walking bass of set-opener "Fat Man And Dancing recently reissued on CD via PolyGram). -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

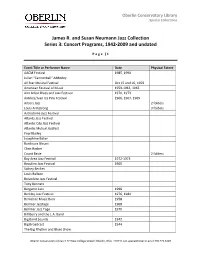

James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and Undated

Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 1 Event Title or Performer Name Date Physical Extent AACM Festival 1985, 1990 Julian "Cannonball" Adderley All Star Musical Festival Oct 15 and 16, 1959 American Festival of Music 1959-1963, 1965 Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival 1970, 1973 Antibes/Juan les Pins Festival 1966, 1967, 1969 Arbors Jazz 2 folders Louis Armstrong 3 folders Astrodome Jazz Festival Atlanta Jazz Festival Atlantic City Jazz Festival Atlantic Mutual Jazzfest Pearl Bailey Josephine Baker Banlieues Bleues Chris Barber Count Basie 2 folders Bay Area Jazz Festival 1972-1973 Beaulieu Jazz Festival 1960 Sidney Bechet Louis Bellson Belvedere Jazz Festival Tony Bennett Bergamo Jazz 1998 Berkley Jazz Festival 1976, 1984 Berkshire Music Barn 1958 Berliner Jazztage 1968 Berliner Jazz Tage 1970 Bill Berry and the L.A. Band Big Band Sounds 1942 Big Broadcast 1944 The Big Rhythm and Blues Show Oberlin Conservatory Library l 77 West College Street l Oberlin, Ohio 44074 l [email protected] l 440.775.5129 Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 2 The Big Show 1957, 1965 The Biggest Show of… 1951-1954 Birdland 1956 Birdland Stars of… 1955-1957 Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers Blue Note Boston Globe Jazz Festival Boston Jazz Festival Lester Bowie British Jazz Extravaganza Big Bill Broonzy Les Brown and His Band of Renown -

A Study Companion

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents A Study Companion 1118 Clearview Pkwy. Metairie, LA 70001 Ph 504.885.2000 Fx 504.885.3437 [email protected] www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher Notes………………………………………………………………………………..………….3 Standards and Benchmarks……………………….………………………..…….………….4 Past, Present and Future……………………………….………………………..………………5 The Play………………………………………………………………………..…………………………….24 Multiplication Rock: the Songs…………………………………………………….……….28 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………………………………………….51 Calculating Rates, Fractions and Graphs ………………………………..52 Parts of Speech and Grammar Rock………………………………………...68 Delirious Descriptive Adjectives...............................73 Science………………………………………………………..………………………….…………82 Additional Resources………………………………………………………….…………………….91 2 | P a g e Teacher Notes Theatre Kids! Presents Schoolhouserock Live! Jr. Lyrics by Bob Dorough Music by Bob Dorough Lyrics by Dave Frishberg Music by Dave Frishberg Book by George Keating Lyrics by George Newall Music by George Newall Lyrics by Kathy Mandry Music by Kathy Mandry Book by Kyle Hall Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens Music by Lynn Ahrens Book by Scott Ferguson Lyrics by Tom Yohe Music by Tom Yohe Based on the ABC-TV educational animated series which aired from the 1970's -1980's One Act, Pop / Rock, Revue, Rated G Broadway Junior Version The Emmy® Award-winning Saturday morning educational cartoon series and pop culture phenomenon is now the basis for one of the most fun and easily mounted musicals ever to hit the stage, SCHOOLHOUSE ROCK LIVE! JR. A loose, revue-like structure allows for a great deal of flexibility in staging and cast size in this energetic musical, which follows Tom, a young school teacher who is nervous about his first day of teaching. He tries to relax by watching TV when various characters representing facets of his personality emerge from the set and show him how to win his students over with imagination and music. -

Late Night Jazz Reprise: Unbeschreiblich Weiblich!

Late Night Jazz Reprise: Unbeschreiblich weiblich! Samstag, 09. März 2019 22.05 - 24.00 Uhr (Erstsendung: 15.4.2017) SRF2 Kultur Fast immer steht in Late Night Jazz der Song im Mittelpunkt, in dieser Ausgabe soll es anders sein. Die Musiker stehen im Zentrum, oder vielmehr die Musikerinnen. Zwei Stunden lang Jazz und jazzverwandtes, nur von Frauen gesungen und vor allem gespielt. Musikerinnen von Lil Hardin bis Heidi Happy sind zu hören, alles andere, vor allem Männer, ist Nebensache! Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Andreas Müller-Crepon Five Play - Plus (2004) Label: Arbors Jazz Track 03: Funk in A Deep Freeze Anat Cohen - Claroscuro (2011) Label: Anzic Track 10: Um A Zero Esperanza Spalding - Disney Jazz Volume I/Everybody Wants to Be A Cat (2010) Label: Walt Disney Track 02: Chim-Chim-Cheree Nicole Johänntgen - Henry (2016) Label: Eigenvertrieb Track 01: Henry Mary Lou Williams - A Keyboard History (1955) Label: Jazztone Track 12: Easy Blues Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong - Ella And Louis Again (1957) Label: Verve CD 02/Track 06: A Fine Romance Melba Liston - Melba Liston And Her Bones (1958) Label: Fresh Sound Track 06: Blues Melba Marian McPartland - 85 Candles, Live In New York (2003) Label: Concord CD 02/Track 02: My Foolish Heart Carmen McRae - Any Old Time (1986) Label: Denon Track 05: I Hear Music Mary Osborn - A Memorial (1959) Label: Stash Track 13: I Love Paris Kathy Stobart - Saxploitation (1976) Label: Spotlight Records Track 01: Softly as In A Morning Sunrise Diana Krall - From This Moment On (2006) Label: Verve -

Lucia Stavros - Harps Songlist

LUCIA STAVROS - HARPS SONGLIST Bach, J.S. "Andante" From Violin Sonata No 2 CLASSICAL Bach, J.S. "Bourrée" From Violin Partita No 1 Bach, J.S. "Fugue" From Violin Sonata No 1 Salzedo Ballade Salzedo Chanson Dans La Nuit Debussy Clair De Lune Mozart Concerto For Flute And Harp Ginastera Concerto For Harp Handel Concerto In Bb Major Renie, H. Contemplation Debussy Danses Sacreé Et Profane Saint-Saens Fantasie For Harp And Violin Grandjany Fantasie On A Theme Of Haydn Desenclos Fantasie Pour Harpe Debussy First Arabesque Salzedo Flight Bach, J.S. French Suite No 6 In E Major Satie Gymnopedie No.1 Faure Impromptu Pierne Impromptu Caprice Ravel Introduction Et Allegro Salzedo Introspection Debussy La Cathedrale Engloutie Debussy La Fille Aux Cheveux De Lin Hasselmans La Source Saint-Saens Le Cyne Presle, J De La Le Jardin Mouille Liszt Liebestraume No 3 Salzedo Mirage Handel Passacaglia Ravel Pavane Pour Une Infante Défunte Watkins Petite Suite Prokofiev Prelude For Harp Rota Sarabande Et Toccata Salzedo Scintillation Persichetti Serenade No 10 Bax Sonata For Flute And Harp Bach, C.P.E. Sonata In G Major Houdy Sonata Pour Harpe Hindemith Sonate Fur Harfe Tournier Sonatine Britten Suite For Harp Damase Tango For Harp Debussy Trio For Flute Harp And Viola Liszt Un Sospiro Lucia Stavros - Harps Songlist 1 of 7 Night Shift Entertainment, LLC. www.nightshiftent.com [email protected] 800 465 1917 Russia Ah! See The Old Pear-Tree (Zéléna Grusha) FOLK Wales All Through The Night (Ar Hyd Y Nos) Germany All's The Same To Me ('S Ist Mir Alles -

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. MOSE ALLISON NEA Jazz Master (2013) Interviewee: Mose Allison (November 11, 1927-) Interviewer: Ted Panken and audio engineer Ken Kimery Dates: September 13-14, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Description: Transcript. 107 pp. Panken: I’m Ted Panken. It’s September 13, 2012. We’re in Eastport, Long Island, with the great Mose Allison, for part one of what we’re anticipating will be a two-session oral history for the Smithsonian in honor of Mose Allison and his Jazz Masters Award. Thank you very much for being here, Mr. Allison, and making us so comfortable. Allison: Thank you. Panken: Let’s start with the facts. Your full name, date of birth, location of birth. Allison: Mose J. Allison, Junior. Date of birth, 11-11-27. Panken: You’re from Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, near Tippo. Allison: Yes. It was just a crossroad. I was born on a farm three miles south of Tippo. Audre Allison: It was called the island. Tippo Creek. Panken: We also have with us, for the record, Audre Allison. You’ve been married over 60 years. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Allison: Yes. Audre Allison: 62, it will be. Or is it already 62? Panken: So I guess you’re qualified to act as a proxy. Allison: Ok. Audre Allison: Well, how much... When I just think that he leaves something out, I should fill in? I don’t want to take over the thing. -

WDR 3 Jazz, 6. Januar 2014 Jazz in Der Ehe 22:00 – 23:00

WDR 3 Jazz, 6. Januar 2014 Jazz in der Ehe 22:00 – 23:00 Stand: 02.01.2014 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de/ Moderation: Götz Alsmann Redaktion: Bernd Hoffmann Laufplan 1. Am I Blue K/T: Clarke / Akst JACKIE CAIN & ROY Kral Fantasy 9643 LP: Bogie 2:38 2. The Glory of Love K/T: Hill JACKIE & ROY Jasmine 1033 LP: The Glory Of Love 3:08 3. In A Little Provincial Town K/T: Jaspar BOBBY JASPAR Columbia FPX 123 LP: Bobby Jaspar Quintet 3:41 4. Chez Moi K/T: Lama BLOSSOM DEARIE Verve 2125 LP: My Gentleman Friend 3:05 5. Anyplace I Hang My Hat Is Home K/T: Arlen / Mercer PEARL BAILEY Roulette 25012 LP: A-Broad 2:36 6. Sticks K/T: Rogers LOUIS BELLSON & THE JUST JAZZ ALL STARS Capitol 926 LP: Hi Fi Drum 3:21 7. Rex Rhumba K/T: Moore / Cole NAT KING COLE Capitol 1551883 LP: Classics 3:19 8. Hey Not Now K/T: Alfred NAT KING COLE & MARIA COLE Capitol 1176 3:05 9. Get Out And Geht Under The Mooon K/T: Shy / Tabias / Jerome wie Titel 8 2:49 Dieses Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des WDR. 1 WDR 3 Jazz, 6. Januar 2014 Jazz in der Ehe 22:00 – 23:00 Stand: 02.01.2014 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de/ 10. I Don’t Mean A Thing K/T: Ellington / Mills DUKE ELLINGTON RCA Victor 541 LP: Jonny Come Lately 3:03 11. -

Jazz Times “She Has That Special Gift You Cannot Buy in a Music Store.” Les Paul “

nickiparrott “ Nicki Parrott could make anyone love jazz!” Cabaret Scene “Nicki brings clear articula- tion, beautiful tone, a sense of rhythmic assuredness and a touch of allure to inven- tive arrangements.” Jazz Times “She has that special gift you cannot buy in a music store.” Les Paul “... at the risk of betraying a certain male penchant I can’t help noting that Parrott is the other lady bassist singer around these days whose beauty matches her musicianship.” Downbeat “There are some performers who have what I would call star quality. It is a combination of talent and charisma that enables them to stand out from the pack, and simply wow an audi- ence.” Joe Lang “...must see... show stop- ping....” Jon Weber, NPR Piano Jazz “...a rarity, a first-class bassist whose playing is as sublime as her vocals.” Limelight A R C D O 5:56 1 Strictly Confidential 1 9 L A R B 4 O R S L (Bud Powell) R E 4 C O R D E S 9 P R I E S E 5:27 RO N T 2 SS S T ockingbird A Sunset and the M NO R SPOR R T (Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn) o IELLO s NIC O KI s P ARR a O P T 3 4:25 n T E n D y’s Wife m D John Hard o I S E i ME o T t Z on) o (Duke Ellingt a O c S c . i p l N s o 4 t a Difference a Day Made 4:14 p Wha r d u A t r d i S ever, English lyrics by Stanley Adams) O (Maria Gr e o d S l N l c e o z O A 4:14 i 5 e I ujah, I Love Him So Hallel r r N R P o s (Ray Charles) i h r c t k u o i NICKI PARROTT a 6 5:31 P Misty b n r a U (Erroll Garner) r a . -

Validating the Voice in the Music of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross

VALIDATING THE VOICE IN THE MUSIC OF LAMBERT, HENDRICKS & ROSS by Lee Ellen Martin Bachelor of Music, McGill University, 2008 Master of Music, The University of Toledo, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Lee Ellen Martin It was defended on March 23, 2016 and approved by Geri Allen, Masters of Music, Associate Professor Michael Heller, PhD, Assistant Professor Farah Jasmine Griffin, PhD Dissertation Advisor: Gavin Steingo, PhD, Assistant Professor ii Copyright © by Lee Ellen Martin 2016 iii VALIDATING THE VOICE IN THE MUSIC OF LAMBERT, HENDRICKS & Ross Lee Ellen Martin, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Lambert, Hendricks & Ross was an unusual vocal jazz trio. Made up of Dave Lambert, Jon Hendricks, and Annie Ross, they were the only interracial and mixed gender vocal jazz group in the United States in the late 1950s. In the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott victory and President Eisenhower’s consideration of the Equal Rights Act, the trio became one of the most popular vocal jazz groups of the day by singing lyricized arrangements of famous instrumental jazz recordings through a medium called vocalese. Although they seemed to reflect a utopian ideal of an integrated American society, each member of the group faced unique challenges. Referred to as the Poet Laureate of Jazz, African American lyricist and singer Jon Hendricks considers himself “a person who plays the horn without the horn,” and he is known for his gift with words.