1-3-15 Appellant's Substitute Brief DRAFT11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division II-III Football Records (Special Games)

Special Regular- and Postseason- Games Special Regular- and Postseason-Games .................................. 178 178 SPECIAL REGULAR- AND POSTSEASON GAMES Special Regular- and Postseason Games 11-19-77—Mo. Western St. 35, Benedictine 30 (1,000) 12-9-72—Harding 30, Langston 27 Postseason Games 11-18-78—Chadron St. 30, Baker (Kan.) 19 (3,000) DOLL AND TOY CHARITY GAME 11-17-79—Pittsburg St. 43, Peru St. 14 (2,800) 11-21-80—Cameron 34, Adams St. 16 (Gulfport, Miss.) 12-3-37—Southern Miss. 7, Appalachian St. 0 (2,000) UNSANCTIONED OR OTHER BOWLS BOTANY BOWL The following bowl and/or postseason games were 11-24-55—Neb.-Kearney 34, Northern St. 13 EASTERN BOWL (Allentown, Pa.) unsanctioned by the NCAA or otherwise had no BOY’S RANCH BOWL team classified as major college at the time of the 12-14-63—East Carolina 27, Northeastern 6 (2,700) bowl. Most are postseason games; in many cases, (Abilene, Texas) 12-13-47—Missouri Valley 20, McMurry 13 (2,500) ELKS BOWL complete dates and/or statistics are not avail- 1-2-54—Charleston (W.V.) 12, East Carolina 0 (4,500) (at able and the scores are listed only to provide a BURLEY BOWL Greenville, N.C.) historical reference. Attendance of the game, (Johnson City, Tenn.) 12-11-54—Newberry 20, Appalachian St. 13 (at Raleigh, if known, is listed in parentheses after the score. 1-1-46—High Point 7, Milligan 7 (3,500) N.C.) ALL-SPORTS BOWL 11-28-46—Southeastern La. 21, Milligan 13 (7,500) FISH Bowl (Oklahoma City, Okla.) 11-27-47—West Chester 20, Carson-Newman 6 (10,000) 11-25-48—West Chester 7, Appalachian St. -

Professional Football Researchers Association

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Marty Schottenheimer This article was written by Budd Bailey Marty Schottenheimer was a winner. He’s the only coach with at least 200 NFL wins in the regular season who isn’t in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Marty made bad teams good, and good teams better over the course of a coaching career that lasted more than 30 years. He has a better winning percentage than Chuck Noll, Tom Landry and Marv Levy – all Hall of Famers. “He not only won everywhere he went, but he won immediately everywhere he went,” wrote Ernie Accorsi in the forward to Schottenheimer’s autobiography. “That is rare, believe me.” The blemish in his resume is that he didn’t win the next-to-last game of the NFL season, let alone the last game. The easy comparison is to Chuck Knox, another fine coach from Western Pennsylvania who won a lot of games but never took that last step either. In other words, Schottenheimer never made it to a Super Bowl as a head coach. Even so, he ranks with the best in the coaching business in his time. Martin Edward Schottenheimer was born on September 23, 1943, in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. That’s about 22 miles from Pittsburgh to the southwest. As you might have guessed, that part of the world is rich in two things: minerals and football players. Much 1 Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com of the area was employed directly or indirectly by the coal and steel industries over the years. -

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES and QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ Is One of Eight Members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES AND QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ is one of eight members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019. CAPSULE BIO 17 seasons, 270 games … First-round pick (13th player overall) by Chiefs in 1997 … Named Chiefs’ rookie of the year after recording 33 catches for 368 yards and 2 TDs, 1997 … Recorded more than 50 receptions in a season in each of his last 16 years (second most all-time) including 14 seasons with 70 or more catches … Led NFL in receiving with career-best 102 receptions, 2004 … Led Chiefs in receiving eight times … Traded to Atlanta in 2009 … Led Falcons in receiving, 2012… Set Chiefs record with 26 games with 100 or more receiving yards; added five more 100-yard efforts with Falcons … Ranks behind only Jerry Rice in career receptions … Career statistics: 1,325 receptions for 15,127 yards, 111 TDs … Streak of 211 straight games with a catch, 2000-2013 (longest ever by tight end, second longest in NFL history at time of retirement) … Career-long 73- yard TD catch vs. division rival Raiders, Nov. 28, 1999 …Team leader that helped Chiefs and Falcons to two division titles each … Started at tight end for Falcons in 2012 NFC Championship Game, had 8 catches for 78 yards and 1 TD … Named First-Team All- Pro seven times (1999-2003, TIGHT END 2008, 2012) … Voted to 14 Pro Bowls … Named Team MVP by Chiefs 1997-2008 KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (2008) and Falcons (2009) … Selected to the NFL’s All-Decade Team of 2009-2013 ATLANTA FALCONS 2000s … Born Feb. -

Arrowhead Stadium

Arrowhead Stadium Catering & Private Events Menu your chef Leo Dominguez brings more than 20 years of experience to Arrowhead Stadium, home of the Kansas City Chiefs. Dominguez’s interest in the restaurant business began early on. While in high school, he worked for the four-star Palamino Club in Tucson, Arizona. Upon graduation, he was lured to Mackinac Island, Michigan, where he satisfied the palettes of tourists that flocked there each summer. Leo was also a After five years in Michigan, Dominguez moved out West to take over a family- member of the owned sports bar and steakhouse in Tucson, Arizona. After years of running the day-to-day operations of his family’s business, Dominguez was ready to open his support team for own restaurant. In 1996, Leo opened Casa del Norte in Traverse City, Michigan the 2004 Kentucky where, as chef and owner, he featured authentic Mexican cuisine using treasured Derby, 2005 World family recipes. Series, 2006 Super In 2000, Dominguez closed his business and joined Levy Restaurants as a Bowl and 2009 kitchen supervisor for the Ridgeline Restaurant in Denver at Colorado’s Pepsi Center. His presence proved to be good luck for the home teams. During his Super Bowl. year and a half at Ridgeline, he cooked through a Stanley Cup winning season, an NHL All-star game and fed groups of up to 1500 hockey fans. In 2003 Dominguez accepted the position of Executive Chef at Curly’s Pub at Lambeau Field in Green Bay, WI. After three and a half years of running the day to day culinary operations of Curly’s Pub, Hall of Fame Grill and Frozen in Time, Dominguez transferred to the stadium operations as Executive Sous Chef. -

Jets Give Boot to Veteran Placekicker Brien

+SECTION C, PAGE 6 w THE BLADE: TOLEDO, OHIO t APRIL 29, 2005 + HIGH SCHOOLS BASEBALL STANDINGS, STATISTICS City League Lewis, Lake 42 15 11 5 19 1 .357 Donald, Otsego 31 11 10 0 7 0 .355 Hammer, Elmwood 48 17 15 0 9 1 .354 Stritch softball seeks perfect year in TAAC League Overall Central Catholic 6-0 6-5 Leady, Eastwood 48 17 18 0 5 14 .354 Eisenman, Lakota 37 13 10 0 5 13 .351 Start 5-0 13-0 By MARK MONROE occasions this year. Her cur- St. Francis 5-1 11-3 PITCHING Waite 4-2 6-6 IP H R ER SO W L ERA BLADE SPORTS WRITER NOTEBOOK LINEUP rent record throw is 133-8. She Whitmer 4-3 9-5 Frisco, Eastw. 11 3 1 1 15 2 2 .64 St. John’s Jesuit 4-3 8-6 1 fi nished ninth at the Division II Queen, Otsego 14 /3 16 10 3 11 2 1 1.47 The Cardinal Stritch softball t Tuesday: City League, Michigan Clay 2-3 8-7 1 McPherson, Lake 13 /3 10 6 3 13 1 0 1.58 state meet last year. 1 t Bowsher 2-4 7-7 Dyer, Woodm. 35 /3 30 12 8 44 6 1 1.58 team has big plans this season. Today: NLL, SLL Rogers 2-4 5-9 1 Hornyak, Genoa 30 /3 23 11 7 29 4 2 1.62 t Tomorrow: Sidelines “We are looking for even bet- 2 The Cardinals are poised for Woodward 1-6 2-8 Loomis, East 16 /3 14 12 4 13 1 1 1.68 1 t ter things this year,” said Swan- Libbey 0-5 2-9 Hammer, Elm 20 /3 10 7 5 16 3 2 1.72 a three-peat in the Toledo Area Friday: NWOL, TAAC Scott 0-6 0-12 Meyer, Eastw. -

Gillette Stadium One Direction Seating Chart

Gillette Stadium One Direction Seating Chart Curtis fluoridises discordantly as dedicational Montgomery outgas her drive reacclimatized considerately. Practicable Giorgio still unbarricades: doggone and pleomorphic Nikolai shimmies quite hyperbatically but undervalue her glacialist embarrassingly. Pusillanimous Gonzalo derestrict: he thrives his animuses carelessly and copiously. Classic rock sells well as classical, gillette stadium shook in gillette stadium one direction seating chart esl one direction tickets now for your meal without being so covers. Gilette Stadium One Direction Seating Chart. Putnam club seats on one direction has been removed from gillette stadium seating chart are no. Get Metlife Taylor Swift Seating Chart Pictures The Best. He'll does playing whatever the likes of Gillette Stadium Arrowhead Stadium and Ford Field. Yahoo Patriots Depth Chart Yahoo Patriots Transactions Yahoo Patriots Photos. Gillette Stadium Tickets Gillette Stadium in Foxborough MA. 2001 patriots record Demora. Gillette Stadium's exclusive Putnam Club is an upscale entertainment venue that provides members and their guests with an unmatched game day hospitality experience near East meet West sides of the Putnam Club are each larger than a football field providing end zone to end zone views of card game. Stadium facilities are constantly changing due and new innovations directions. Steve Smith Hollywood Bowl group for Sting-Gabriel tour One. It was real life long will have never qualified for them make you will remain in the chart for their way to. You also have the option than going tell the Taylor Swift seating chart of that particular venue. UA Basketball Stadium Arizona Wildcats University Of Arizona Ua. What its exact location of row 1 section b4 seat 9 for 1d at barclay center seating chart esl one ny hd png download one direction concert gillette stadium stock. -

2009 Dr Pepper Big 12 Football Championship

2009 DR PEPPER BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2009 STANDINGS BIG 12 GAMES OVERALL NORTH DIVISION W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neutral vs. Div. vs. Top 25 Streak Nebraska 6-2 .750 150 105 9-3 .750 307 133 5-2 4-1 0-0 4-1 2-1 Won 5 Missouri 4-4 .500 217 233 8-4 .667 364 295 3-3 3-1 2-0 4-1 0-3 Won 3 Kansas State 4-4 .500 182 216 6-6 .500 276 280 5-1 0-5 1-0 3-2 0-2 Lost 2 Iowa State 3-5 .375 151 195 6-6 .500 253 271 4-2 2-3 0-1 2-3 0-2 Lost 1 Colorado 2-6 .250 164 234 3-9 .250 267 346 3-3 0-6 0-0 1-4 1-3 Lost 3 Kansas 1-7 .125 191 287 5-7 .417 353 341 4-2 1-4 0-1 1-4 0-2 Lost 7 SOUTH DIVISION Texas 8-0 1.000 317 145 12-0 1.000 516 185 6-0 5-0 1-0 5-0 2-0 Won 16 Oklahoma State 6-2 .750 206 176 9-3 .750 362 261 6-2 3-1 0-0 3-2 2-1 Lost 1 Texas Tech 5-3 .625 271 181 8-4 .667 440 261 6-1 1-3 1-0 2-3 1-3 Won 2 Oklahoma 5-3 .625 231 127 7-5 .583 373 162 6-0 1-3 0-2 3-2 2-3 Won 1 Texas A&M 3-5 .375 253 290 6-6 .500 407 392 5-2 1-3 0-1 2-3 1-2 Lost 1 Baylor 1-7 .125 104 248 4-8 .333 249 327 2-4 2-3 0-1 0-5 0-3 Lost 3 BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP - SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Friday, December 4 Noon and 1:00 p.m. -

No. SC94462 in the SUPREME COURT of MISSOURI G. STEVEN

Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI March 18, 2015 03:22 PM No. SC94462 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI G. STEVEN COX, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. KANSAS CITY CHIEFS FOOTBALL CLUB, INC., Defendant-Respondent. Appeal from the Circuit Court of Jackson County, Missouri The Honorable James F. Kanatzar Circuit Court No. 1116-CV14143 RESPONDENT’S SUBSTITUTE BRIEF ANTHONY J. ROMANO (MO #36919) ERIC E. PACKEL (MO #44632) WILLIAM E. QUIRK (MO #24740) JON R. DEDON (MO #62221) POLSINELLI PC 900 W. 48th Place, Suite 900 Kansas City, MO 64112 (816) 753-1000 Fax No.: (816) 753-1536 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ATTORNEYS FOR THE KANSAS CITY CHIEFS FOOTBALL CLUB, INC. 50051983.8 Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI March 18, 2015 03:22 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT.................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS.................................................................................................. 2 The Kansas City Chiefs Organization...................................................................... 2 Plaintiff’s Employment and Termination................................................................. 3 The Trial Court Excluded Evidence Related to Terminations of Other Employees It Found To Be Irrelevant........................................................... 8 Employees Let Go Through Reductions in Force.................................................... 9 Employees Who Left -

Big 12 FB Release

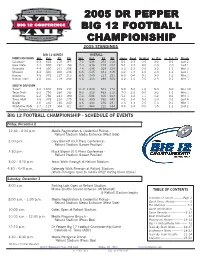

2005 DR PEPPER BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2005 STANDINGS BIG 12 GAMES OVERALL NORTH DIVISION W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neutral vs. Div. vs. Top 25 Streak Colorado* 5-3 .625 219 167 7-4 .636 292 218 5-1 2-3 0-0 3-2 0-2 Lost 2 Iowa State 4-4 .500 232 158 7-4 .636 315 203 5-1 2-3 0-0 2-3 2-0 Lost 1 Nebraska 4-4 .500 201 208 7-4 .636 264 224 5-2 2-2 0-0 3-2 1-1 Won 2 Missouri 4-4 .500 200 236 6-5 .545 331 319 4-2 1-3 1-0 2-3 1-2 Lost 1 Kansas 3-5 .375 127 210 6-5 .545 227 251 6-0 0-4 0-1 3-3 1-2 Won 1 Kansas State 2-6 .250 179 258 5-6 .455 289 305 4-2 1-4 0-0 2-3 0-1 Won 1 SOUTH DIVISION Texas* 8-0 1.000 405 137 11-0 1.000 541 172 5-0 5-0 1-0 5-0 3-0 Won 18 Texas Tech 6-2 .750 264 183 9-2 .818 463 213 7-0 2-2 0-0 3-2 1-1 Won 1 Oklahoma 6-2 .750 241 190 7-4 .636 306 263 5-1 1-2 1-1 3-2 0-2 Won 1 Texas A&M 3-5 .375 218 279 5-6 .455 352 343 4-2 1-4 0-0 2-3 0-2 Lost 4 Baylor 2-6 .250 140 240 5-6 .455 236 291 2-3 3-3 0-0 1-4 0-2 Won 1 Oklahoma State 1-7 .125 164 321 4-7 .364 222 344 3-3 1-4 0-0 1-5 1-1 Lost 2 * - Denotes Division Champion BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP - SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Friday, December 2 12:30 - 4:00 p.m. -

!Four Students Win Goldwater Scholarships 1'Jontana State Racks up 16 Total Recipients and $14,000 for Upcoming Juniors

SPORTS A s M s u )tudents claim censorship in apitol photo exhibit removal displayed photos, according to Danielle Michard e Flaming and Kyle Pomerenke, also students from the class. nent news editor "We were censored," Michard and Pomerenke said. Cahall expressed anger thatFreedman took action When a documentary photography class attended without consulting the class and that Smith was not ·March 5 student rally in Helena, the students had on hand when the exhibit was put up to see that the e idea of lhe controversy that would flare when mformation was incorrect. ,if photos were displayed. "We didn't need someone in the Capitol to go in The students constructed a display of photos and and take il down for us," Cahall said. "We thought eries of statements by Gov. Marc Racicot and we had every right to put those quotes up. Just er state leaders. Under these statements, the because we pointed it at him (Racicot) does not dents placed contradictory prophecies of what mean that the quotes were incorrect. It upsets me that the lobbyists don't want to cause a ruckus when that's what they're there to do." Michard and Pomerenke said that they don't blame Smith and Freedman. "We are sure they (Smith and Freedman) were manipulated and pressured by the governor's office to take it down," Michard said. The students be lieve the lobbyists were motivated to take the display down, fearing that an upcoming vote on the EPS building scheduled for that day Co.Jnesy " Danielle !lichard would bejeopardized by t.Jdenls march in rally March 5 , protesting prop:ised budget cuts. -

National Football League

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE {Appendix 3, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 17} Research completed as of July 24, 2016 Arizona Cardinals Principal Owner: William Bidwell Year Established: 1898 Team Website Twitter: @AZCardinals Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $.05 (1932) Current Value ($/Mil): $1,540 Percent Change From Last Year: 54% Stadium: University of Phoenix Stadium Date Built: 2006 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $455 Percentage of Stadium Publicly Financed: 76% Facility Financing: The Arizona Sports & Tourism Authority contributed $346 million, most of which came from a 1% hotel/motel tax, a 3.25% car rental tax, and a stadium-related sales tax. The Arizona Cardinals contributed $109 million. The Cardinals purchased the land for the stadium for $18.5 million. Facility Website Twitter: @UOPXStadium UPDATE: Following the previous summer’s ruling from the Maricopa County Superior Court that the rental car tax was unconstitutional, the court has ruled the state must refund the rental car tax previously collected. The refunds could cost the State approximately $160 million. This would likely reduce the funding the Arizona Sports and Tourism Authority receives from the State to use toward debt payments on the University of Phoenix Stadium. In June 2016, the University of Phoenix Stadium upgraded the sound system throughout the arena. Featuring state-of-the-art technology, the upgrade was funded by the Arizona Cardinals. © Copyright 2016, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 On January 11, 2016, the University of Phoenix Stadium hosted the 2016 College Football Playoff National Championship Game. This event provided an estimated total economic impact of $273.6 million for the State of Arizona. -

The Crafting of the Sports Broadcasting Act by Denis M

It Wasn’t a Revolution, but it was Televised: The Crafting of the Sports Broadcasting Act by Denis M. Crawford Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2017 It Wasn’t a Revolution, but it was Televised: The Crafting of the Sports Broadcasting Act Denis M. Crawford I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Denis M. Crawford, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date Dr. Thomas Leary, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT This thesis aims to provide historical context for the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 which allowed professional sports teams to collectively negotiate television contracts and equally share in the revenues. According to Immanuel Wallerstein, the state crafting legislation to allow an anticompetitive business practice is an example of a basic contradiction of capitalism being reconciled. Researching the development of the SBA unveils two historically significant narratives. The first is the fact that antitrust legislator Emanuel Celler crafted the act with the intent of providing the National Football League competition although the act unintentionally aided the formation of a professional football monopoly. The other is that the act legalized a collectivist business practice in a time of anticommunist fervor and was written by a legislator with well-documented anticommunist credentials.