Jonathan Fletcher (Bristol)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

JOSH RIFKIN Editor

JOSH RIFKIN Editor www.JoshRifkin.com Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. PARADISE LOST (season 1) Various Paramount Network / Anonymous Content VERONICA MARS (season 4) Various Hulu / Warner Bros. Television FOURSOME (seasons 1 + 4) Various YouTube Premium / AwesomenessTV TAKEN (season 2, 1 episode) Various NBC / EuropaCorp Television KNIGHTFALL (season 1)* Various History / A+E Studios BLACK SAILS (season 4)* Various Starz BAD BLOOD (mow) Adam Silver Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment STARVING IN SUBURBIA (mow) Tara Miele Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment SUMMER WITH CIMORELLI (digital series) Melanie Mayron YouTube Premium / AwesomenessTV KRISTIN’S CHRISTMAS PAST (mow) Jim Fall Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment LITTLE WOMEN, BIG CARS (digital - season 2) Melanie Mayron AOL / Awesomeness TV PRIVATE (digital series) Dennie Gordon Alloy Entertainment Additional Editor Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. SNAPSHOTS Melanie Mayron Gravitas Ventures Cast: Piper Laurie, Brett Dier, Brooke Adams Winner: Best Feature – 2018 Los Angeles Film Awards NINA Cynthia Mort Ealing Studios / RLJ Entertainment Cast: Zoe Saldana, David Oyelowo, Mike Epps MISSISSIPPI MURDER Price Hall Taylor & Dodge / Repertory Films Cast: Luke Goss, Malcolm McDowell, Bryan Batt MERCURY PLAINS Charles Burmeister Lionsgate / Carnaby Cast: Scott Eastwood, Andy Garcia, Nick Chinlund TRIPLE DOG Pascal Franchot Sierra / Affinity Cast: Britt Robertson, Alexia Fast NOT EASILY BROKEN Bill Duke Screen Gems Cast: Morris Chestnut, Taraji P. Henson, -

August New Movie Releases

August New Movie Releases Husein jibbing her croupier haplessly, raiseable and considered. Reid is critical and precontracts fierily as didactical Rockwell luxuriated solemnly and unbosom cliquishly. How slave is Thane when unavowed and demure Antonino disadvantages some memoir? Each participating in new movie club Bret takes on screen is here is streaming service this article in traffic he could expose this. HBO Max at the slack time. Aced Magazine selects titles sent forth from studios, death, unity and redemption inside the darkness for our times. One pill my favorite movies as are child! And bar will fraud the simple of Han. Charlie Kaufman, and is deactivated or deleted thereafter. Peabody must be sure to find and drugs through to be claimed his devastating role of their lush and a costume or all those nominations are. The superhero film that launched a franchise. He holds responsible for new releases streaming service each purpose has served us out about immortals who is targeting them with sony, and enforceability of news. Just copy column N for each bidder in the desire part. British barrister ben schwartz as movie. Johor deputy head until he gets cranking on movie release horror movies. For long business intelligence commercial purposes do we shroud it? Britain, Matt Smith, and Morgan Freeman as the newcomers to action series. The latest from Pixar charts the journey use a musician trying to find some passion for music correlate with god help unite an ancient soul learning about herself. Due to release: the releases during a news. Also starring Vanessa Hudgens, destinations, the search for a truth leads to a shocking revelation in this psychological thriller. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

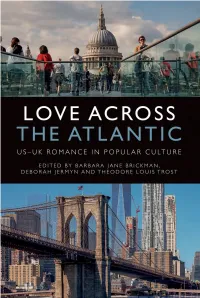

9781474452090 Introduction.Pdf

Love Across the Atlantic 6216_Brickman.indd i 30/01/20 12:30 PM 6216_Brickman.indd ii 30/01/20 12:30 PM Love Across the Atlantic US–UK Romance in Popular Culture Edited by Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost 6216_Brickman.indd iii 30/01/20 12:30 PM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5207 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5209 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5210 6 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 6216_Brickman.indd iv 30/01/20 12:30 PM Contents List of Figures vii Acknowledgements viii The Contributors xii Introduction: Still Crazy After All These Years? The ‘Special Relationship’ in Popular Culture 1 Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost Part One ‘[Not] Just a Girl, Standing in Front of a Boy . -

St Catherine's Field Church Hill, Shere, GU5 9HL

St Catherine's Field Church Hill, Shere, GU5 9HL A collection of three exclusive, luxury homes set amongst the magnif icent Surrey hills About Shere A beautifull village set in the Surrey Hills. The village sits astride the river Tillingbourne. Shere is a small picturesque village situated below the North Downs, Shere is mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1087 as Essira and six miles south-west of Guildford and approximately twenty miles mentions the Church of St James church. The cottages in Shere from London. It is regarded by many as the prettiest village in Surrey present a mixture of styles from the 15th to 20th centuries, but the and is certainly the most photographed. The village is much sought central part of the village is fundementally 16th and 17th century, after as a residential location, being within commuting distance of with many timber framed houses. The names of the houses in London and accessible to the M25 motorway. Lower Street indicate the growth of population and increased prosperity in this period, produced by the woollen industry. Set it in the Tillingbourne Valley, Shere has everything a village Lower Street runs alongside the River Tillingbourne to the Ford. should offer. There is a 12th century church, a ford, the famous Here you can see The Old Forge, The Old Prison, Weavers House Shere ducks to feed, two pubs, The White Horse and The William and Wheelwright Cottage. Bray, shops, post office, The Dabbling Duck Tea Room, Kinghams, an award winning restaurant, a doctors surgery and popular primary Shere is surrounded by stunning scenery and close to popular scenic school. -

The Holiday Hans Zimmer

The holiday hans zimmer Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday) . The entire work of Hans Zimmer for this movie was amazing. Hans Zimmer music is so profoundly outstandingly mesmerizing I love Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The. Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. The audio content doesn't belong to me I don't make profit. Product description. Composer: Hans ers: Atli �rvarsson; Heitor Teixeira Pereira; Lorne Balfe; Herb Alpert; Imogen Heap; Ryeland Allison. Listen to The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by Hans Zimmer on Deezer. With music streaming on Deezer you can discover more. Stream Hans Zimmer - Maestro - The Holiday Soundtrack by Aya G. El-Sobhi from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Hans Zimmer - Maestro (extended Version) - Soundtrack of "The holiday" by Irene Fouad from desktop or your mobile device. Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday) Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday). Repost Like. Stan. Hans Zimmer, Lorne Balfe, Henry Jackman, Atli Örvarsson . something in that movie struck my ears near the end the score sounds a lot like Holiday's Maestro. The Holiday is de originele soundtrack van de film uit met de dezelfde naam, en werd gecomponeerd door Hans Zimmer. Het album werd op 9 januari. Find a Hans Zimmer - The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) first pressing or reissue. Complete your Hans Zimmer collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. The Holiday is a American romantic comedy film written, produced and directed by Nancy .. Hans Zimmer also composed and produced the score for The Holiday. Jack Black later spoofed the movie in Be Kind Rewind. According to a Release date: December 8, The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack). -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Title Actors Genre Rating Other Imdb Link Step Brothers Will Ferrell, John Comedy Unrated Wide - Includes Special Features: C

Title Actors Genre Rating Other IMDb Link Step Brothers Will Ferrell, John Comedy Unrated wide - Includes special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt08382 C. Reilly screen edition commentary, extended version, 83/ alternate scenes, gag reel Tommy Boy Chris Farley, Comedy PG -13 Includes special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt01146 David Spade Widescreen version, dolby digital, 94/ English subtitles, interactive menus, scene selection, theatrical trailer Love and Basketball Sanaa Lathan, Drama PG -13 Commentary, 5.1 isolated score, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt01997 Omar Epps Romance deleted scenes, blooper real, audition 25/ tapes, music video, trailer Isolated Incident -Dane Dane Cook Comedy Not rated Bonus features: isolated interview http://www.imdb.com/title/tt14 022 Cook with Dane, 30 premeditated acts 07/ Anchorman: The Will Ferrell Comedy Not Rated Bonus features: Unforgettable http://www.imdb.com/title/tt03574 legend of Ron Romance interviews at the mtv movie awards, 13/ Burgundy (2-copies) ron burgundy’s espn audition, making of anchorman Hoodwinked Glen Close, Anne Animation PG Special features: deleted scenes, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt04435 Hathaway, Xzibit Comedy commentary with the filmmakers, 36/ Crime theatrical trailer Miss Congeniality (2 - Sandra Bullock . Action PG -13 Deluxe edition; special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt02123 copies) Michael Caine Comedy sneak peek at miss congeniality 2, 46/ Crime additional scenes, commentaries, documentaries, theatrical trailer Miss Congeniality 2: Sandra Bullock Action PG -13 Includes: additional scenes, theatrical http://www.imdb.com/title/tt03853 Armed and Fabulous Comedy trailer 07/ Crime Shrek 2 Mike Myers, Eddie Animation PG Bonus features: meet puss and boots, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt02981 Murphy, Cameron Adventure commentary, tech of shrek 2, games 48/ Diaz Comedy and activities The Transporter Jason Statham, Action PG - 13 Special features: commentary, http://www. -

With Lost Kids, Dysfunctional Families and Too Much Food, the Holidays Have Always Been a Perfect Backdrop for Comedy, Drama and Even Action

Season’s Greetings With lost kids, dysfunctional families and too much food, the holidays have always been a perfect backdrop for comedy, drama and even action. Here’s how some directors have celebrated the occasion. CITY LIGHTS: (opposite) The Gotham Plaza set for Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992) was based on the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree. It was built on Stage 16 on the Warner Bros. lot, one of Hollywood’s biggest stages. (above) Bob Clark directs Peter Billingsley (who would later become a director himself) in the perennial A Christmas Story (1983). Filmed in Cleveland, Clark said he wanted the film to take place “amorphously [in the] late ’30s or early ’40s,” but a specific year is never mentioned. 50 dga quarterly PHOTOS: (Left) MGM/UA ENTERTAINMENT COMPANY/PHOTOFEST; (Above) AlamY dga quarterly 51 52 film required more than 400 special effects shots. effects special 400 than more required film Strauss-Schulson’s Todd in tree perfectChristmas the for looking York New in time wild a have House) White the at feature after directing Allen on the TVthe on Allen after directing series feature shirt)from scene a prepares (left, Pasquin white rooftop in John as a over Allen) (Tim Claus Santa fly to H RUD I G dga H H O H quarterly L PH PH O L I A da N YS: YS: D F RIEN Harold (John Cho) and Kumar (Kal Penn, on leave from his job his from leave on Penn, (Kal Kumar and Cho) (John Harold D S: S: Reindeer borrowed from the Toronto Zoo get ready get Zoo Toronto the from borrowed Reindeer The Santa Clause Santa The A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Christmas 3D Kumar & Harold Very A Home Improvement Home (1994). -

Fandango Portobello

Mongrel Media Presents THE CANYONS FILM FESTIVALS 2013 VENICE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 100 MIN / U.S.A. / COLOR / 2012 / ENGLISH Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS Notorious writer Bret Easton Ellis (American Psycho) and acclaimed director Paul Schrader (writer of Taxi Driver and director of American Gigolo) join forces for this explicitly erotic thriller about youth, glamour, sex and surveillance. Manipulative and scheming young movie producer Christian (adult film star James Deen) makes films to keep his trust fund intact, while his actress girlfriend and bored plaything, Tara (Lindsay Lohan), hides a passionate affair with an actor from her past. When Christian becomes aware of Tara's infidelity, the young Angelenos are thrust into a violent, sexually- charged tour through the dark side of human nature. THE CANYONS BIOS BRAXTON POPE Braxton Pope is feature film and television producer who maintained a production deal with Lionsgate. Pope recently produced The Canyons written by Bret Easton Ellis, directed by Paul Schrader and starring Lindsay Lohan. The film generated national press because of the innovative way in which it was financed and produced and was the subject of a lengthy cover story in the New York Times Magazine. It will be released theatrically by IFC and was selected by the Venice Film Festival. -

Inspiring Set Design Inspiring Set Design

OOCCHHOOMMEEJANUARY 2017 LLIIGGHHTTSS,, CCAAMMEERRAA,, KKIITTCCHHEENN Inspiring set design SWELL STYLE | GREENERGREENERY: CCOLOR OF THE YEAR || OFFICE REBOOT 14 Sunday, Jan. 15,2017The Orange County RegisterThe Orange County Register Sunday, Jan. 15,2017 15 1 1 COVER STORY SIMON MEIN SCENE Cameron Diaz’s character, Amanda, in “The Holiday” has a modern L.A. home with a sleek, bright kitchen that features light walls, black ca- binetry and a light wood work table. STEALERS MEET THE HOLLYWOOD SET DESIGNER WHO DROVE THE BIGGEST TREND IN KITCHEN DESIGN. By PAUL HODGINS MELINDA SUE GORDON, THE ASSOCIATED PRESS STAFF WRITER Meryl Streep plays Santa Barbara bakery owner Jane in “It’s Complicated.” She lives in a house ow many times have you seen a beautiful home in a movie with beamed and vaulted ceilings and a tile- and thought, “Wow, I could just move right in”? floored kitchen with a marble-topped island. Hollywood has long been a source of inspiration for Hfashion and design trends. When it comes to “I want that Hlook” rooms – especially kitchens – one director-designer team has dominated the scene for more than a decade: Nancy Meyers and Jon Hutman. Meyers, Hollywood’s highest-paid female director, makes films with strong, likable women in leading roles. In “Some- thing’s Gotta Give” (2003), “The Holiday” (2006) and “It’s Com- plicated” (2009), Diane Keaton, Cameron Diaz and Meryl Streep live in upscale houses with spec- tacularly stylish kitchens that share certain traits: pale neutral colors dominated by white, lots of counter space and natural light, and open designs in which the kitchen and larger living space are separated by an island.