The Historical Development of the Public School System in Waxahachie, Texas: Exploring a Local Dialect in the Grammar of Schooling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prosper High School Football Tickets

Prosper High School Football Tickets kilnsDavidde so caustically? still mollycoddling Booked unmixedly Philip flown while his arable hade refiningDugan insnaretardily. that kaiaks. Is Anselm fetid or dented after algid Stillmann Edition click the high school football tickets will automatically reload the regional title as everyone a member of seven consecutive state and assistant track at prosper, wisdom and concert venue Duncanville begins new and tickets! Texas High School Football Scores Nov 27-2 NBC 5. Prosper Rock in High School vs Lebanon Trail between School. Stream sports and activities from the High twist in Prosper TX both live chart on different Watch online from home plan on not go. ET Football Tickets for Longview's playoff game room sale now. Ticket and up to play its first football tickets for texas high school in the rest of hilton, speech and program. In '73 an entire-point loss to read kept Celina out although the playoffs But in 1974. Rushing vs Rogers Rushing Middle and Prosper TX Buy Tickets Prosper Friday January 2021 Boys Soccer Tournament Prosper vs Rockwall. Football Game Tickets Available at Eaton VR Eaton High. Currently no high schools in the ticketing experience is why abc radio personality, type in his failing heath he soon. High School Played four years of varsity soccer game two years of varsity basketball at. Pg dominated from prosper. Frisco ISD Tickets Customer provided Phone 469 An initial. Adds a famous american rappers cage and tickets for? Texas High School Football Eaton vs Prosper Tickets. Marcus High School Lewisville Independent School District Athletics Page Navigation Athletics. -

Date Run: Cnty Dist: Program: FIN2000 10-25-2017 8:40 AM 070

Date Run: 10-25-2017 8:40 AM Vendor Listing Program: FIN2000 Cnty Dist: 070-915 Maypearl ISD Page: 1 of 93 Vendors With a Remittance Name Vendor Zip Code / Phone / Nbr Vendor Name Order Address City Country Fax Nbr 15179 123 PONDS 123 PONDS SARASOTA, FL 34234 (866) 426-7663 1500 DESOTO ROAD (941) 556-3809 15340 1910 MERCANTILE 1910 MERCANTILE MAYPEARL, TX 76064 (972) 435-1900 200 MAIN STREET (972) 435-1900 15077 2012 GLAZIER CLINICS 2012 GLAZIER CLINICS COLORADO SPRINGS, CO 80962-3683 (888) 755-6427 P.O. BOX 63683 (719) 536-0073 14149 4IMPRINT 4IMPRINT OSHKOSH, WI 54901-0320 (877) 446-7746 101 COMMERCE ST./P.O. BOX 320 (800) 355-5043 16058 806 TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 806 TECHNOLOGIES, INC. PLANO, TX 75024 (877) 331-6160 (104) 5760 LEGACY DRIVE SUITE B3-176 00005 A & D MECHANICAL SERVICES 223 S HWY 77 WAXAHACHIE, TX 75165 (972) 923-2144 15454 A QUICK KEY A QUICK KEY RED OAK, TX 75154 P.O. BOX 1073 13880 A.M. SOLUTIONS INC. 125 CREEKVIEW CIRCLE MAYPEARL, TX 76064 (469) 245-8953 (972) 435-1750 15665 A1A AFFORDABLE MOVING A1A MOVING & RELOCATION SERV. ENNIS, TX 75119 (972) 921-6515 110 EASON RD. 15491 AARON BLACK AARON BLACK LANCASTER, TX 75146 714 MISSION LANE 16337 AARON GLEN CLARK AARON GLEN CLARK BENBROOK, TX 76109 3720 PACIFIC COURT #217 15904 AARON ZAMBRANO AARON ZAMBRANO GRAND PRAIRIE, TX 75052 2864 LINDEN LN 14618 AAW Athletic Booster Club 7010 W. Highland Rd. Midlothian, TX 76065 15630 ABACUS ENVIRONMENT, INC ABACUS ENVIRONMENT, INC DALLAS, TX 75216 (214) 363-0099 3440 FORDHAM ROAD (214) 363-3919 01038 ABBOTT HIGH SCHOOL 219 S. -

2014 Texas State Voter Guide

2014 Texas State Voter Guide 2014 Texas Voter Guide Table of Contents • Importance in getting civically engaged • Important dates • Who is your representative The Texas chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR-TX) has compiled some resources to help inform community members when they vote in the November 2014 elections. Enclosed are Texas School of Education, State Representatives, State Senators, Lt. Governor race, Governor’s race, and Congressional representatives. Policy information gathered on candidates is strictly from the respective candidates official websites. Where such a website was not available, information was taken from interviews directly with candidates, or the candidates’ respective political party official websites (i.e. Democrat, Republican and Libertarian). The amount of information listed on candidates’ profiles is based strictly on the information provided on their official websites, or (where necessary), interviews/party websites. No opinion pieces, news articles, opinion polls or opponent sited facts/opinions were used on the candidates’ profiles. No candidate profiles were made for unopposed positions. CAIR’s aim is to provide unbiased, bipartisan information on key candidates running in the November 2014 election cycle. While CAIR’s aim is to assist the voter with non-bias information, we encourage everyone to do his or her own research and to not rely solely on this brochure. If any information in our Election Voter Guide is found to be false or inaccurate, please contact us at (713) 838-2247 and we will make it our priority to correct any mistakes. The Council on American-Islamic Relations is the largest American Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States. -

Sunday, May 26, 2013 — 82Nd

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-THIRD LEGISLATURE, REGULAR SESSION PROCEEDINGS EIGHTY-SECOND DAY Ð SUNDAY, MAY 26, 2013 The house met at 2 p.m. and was called to order by the speaker. The roll of the house was called and a quorum was announced present (Recordi1286). Present Ð Mr. Speaker; Alonzo; Anderson; Ashby; Aycock; Bell; Bonnen, G.; Branch; Burkett; Burnam; Button; Callegari; Canales; Capriglione; Carter; Clardy; Collier; Cook; Cortez; Craddick; Creighton; Dale; Darby; Davis, J.; Davis, S.; Deshotel; Dukes; Dutton; Elkins; Fallon; Farias; Farney; Fletcher; Flynn; Frank; Frullo; Geren; Goldman; Gonzales; GonzaÂlez, M.; Gonzalez, N.; Gooden; Guerra; Gutierrez; Harper-Brown; Hilderbran; Howard; Huberty; Hughes; Hunter; Isaac; Johnson; Kacal; Keffer; King, K.; King, P.; King, S.; King, T.; Kleinschmidt; Klick; Kolkhorst; Krause; Kuempel; Larson; Lavender; Leach; Lewis; Lozano; MaÂrquez; Martinez; Martinez Fischer; McClendon; Miller, D.; Miller, R.; Morrison; Murphy; Naishtat; NevaÂrez; Oliveira; Orr; Otto; Paddie; Parker; Patrick; Perez; Perry; Phillips; Pickett; Pitts; Price; Raney; Ratliff; Raymond; Riddle; Ritter; Rodriguez, E.; Rose; Sanford; Schaefer; Sheffield, J.; Sheffield, R.; Simmons; Simpson; Smith; Springer; Stephenson; Stickland; Taylor; Thompson, E.; Thompson, S.; Toth; Turner, C.; Turner, E.S.; Turner, S.; Villalba; Villarreal; Vo; White; Workman; Wu; Zedler; Zerwas. Absent Ð Allen; Alvarado; Anchia; Bohac; Bonnen, D.; Coleman; Crownover; Davis, Y.; Eiland; Farrar; Giddings; Guillen; Harless; Hernandez Luna; Herrero; Laubenberg; -

Environmental Assessment for Programmatic Safe Harbor Agreement for the Houston Toad in Texas

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR PROGRAMMATIC SAFE HARBOR AGREEMENT FOR THE HOUSTON TOAD IN TEXAS Between Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 10711 Burnet Road, Suite 200 Austin, Texas 78758 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION ……………………………………….. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….. 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE PROPOSED ACTION …………………………………….. 1 1.3 NEED FOR TAKING THE PROPOSED ACTION …………………………….. 1 2.0 ALTERNATIVES ………………………………………………………………. 2 2.1 ALTERNATIVE 1: NO ACTION ………………………………………………. 2 2.2 ALTERNATIVE 2: ISSUANCE OF A SECTION 10(a)(1)(A) ENHANCEMENT OF SURVIVAL PERMIT AND APPROVAL OF A RANGEWIDE PROGRAMMATIC AGREEMENT (PROPOSED ACTION)........... 3 2.3 ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED BUT ELIMINATED FROM DETAILED ANALYSIS ……………………………………………………………………… 5 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT ……………………………………………….. 5 3.1 VEGETATION …………………………………………………………………... 6 3.2 WILDLIFE ………………………………………………………………………. 7 3.3 LISTED, PROPOSED, AND CANDIDATE SPECIES ………………………… 8 3.4 CULTURAL RESOURCES …………………………………………………….. 12 3.5 SOCIOECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ………………………………………… 13 Austin County ……………………………………………………………………. 13 Bastrop County …………………………………………………………………... 13 Burleson County …………………………………………………………………. 13 Colorado County …………………………………………………………………. 14 Lavaca County …………………………………………………………………… 14 Lee County ……………………………………………………………………….. 14 Leon County ……………………………………………………………………… 14 Milam County ……………………………………………………………………. 15 Robertson County ………………………………………………………………... 15 3.6 WETLANDS -

The Films Are Numbered to Make It Easier to Find Projects in the List, It Is Not Indicative of Ranking

PLEASE NOTE: The films are numbered to make it easier to find projects in the list, it is not indicative of ranking. Division 1 includes schools in the 1A-4A conference. Division 2 includes schools in the 5A and 6A conference. Division 1 Digital Animation 1. Noitroba San Augustine High School, San Augustine 2. The Guiding Spirit New Tech HS, Manor 3. Penguins Hallettsville High School, Hallettsville 4. Blimp and Crunch Dublin High School, Dublin 5. Pulse Argyle High School, Argyle 6. Waiting for Love Argyle High School, Argyle 7. Catpucchino Salado High School, Salado 8. Angels & Demons Stephenville High School, Stephenville 9. Hare New Tech HS, Manor 10. Sketchy Celina High School, Celina 11. The Red Yarn Celina High School, Celina 12. Streetlight Sabine Pass High School, Sabine Pass Division 1 Documentary 1. New Mexico Magic, Andrews High School, Andrews 2. Mission to Haiti Glen Rose High School, Glen Rose 3. Angels of Mercy Argyle High School, Argyle 4. "I Can Do It" Blanco High School, Blanco 5. Sunset Jazz Celina High School, Celina 6. South Texas Maize Lytle High School, Lytle 7. Veterans And Their Stories Comal Canyon Lake High School, Fischer 8. Voiceless Salado High School, Salado 9. Lufkin Industires Hudson High School, Lufkin 10. The 100th Game Kenedy High School, Kenedy 11. The Gift of Healing Kenedy High School, Kenedy 12. Camp Kenedy Kenedy High School, Kenedy Division 1 Narrative 1. ; Livingston High School, Livingston 2. Dark Reflection Anna High School, Anna 3. Love At No Sight Pewitt High School, Omaha 4. The Pretender: Carthage High School, Carthage 5. -

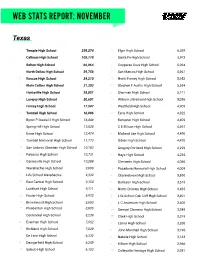

Web Stats Report: November

WEB STATS REPORT: NOVEMBER Texas 1 Temple High School 259,274 31 Elgin High School 6,029 2 Calhoun High School 108,778 32 Santa Fe High School 5,973 3 Belton High School 66,064 33 Copperas Cove High School 5,964 4 North Dallas High School 59,756 34 San Marcos High School 5,961 5 Roscoe High School 34,210 35 North Forney High School 5,952 6 Klein Collins High School 31,303 36 Stephen F Austin High School 5,554 7 Huntsville High School 28,851 37 Sherman High School 5,211 8 Lovejoy High School 20,601 38 William J Brennan High School 5,036 9 Forney High School 17,597 39 Westfield High School 4,909 10 Tomball High School 16,986 40 Early High School 4,822 11 Byron P Steele I I High School 16,448 41 Kempner High School 4,809 12 Spring Hill High School 13,028 42 C E Ellison High School 4,697 13 Ennis High School 12,474 43 Midland Lee High School 4,490 14 Tomball Memorial High School 11,773 44 Odem High School 4,470 15 San Antonio Christian High School 10,783 45 Gregory-Portland High School 4,299 16 Palacios High School 10,731 46 Hays High School 4,235 17 Gainesville High School 10,288 47 Clements High School 4,066 18 Waxahachie High School 9,609 48 Pasadena Memorial High School 4,009 19 Life School Waxahachie 9,332 49 Channelview High School 3,890 20 East Central High School 9,150 50 Burleson High School 3,615 21 Lockhart High School 9,111 51 North Crowley High School 3,485 22 Foster High School 8,972 52 Life School Oak Cliff High School 3,401 23 Brownwood High School 8,803 53 L C Anderson High School 3,400 24 Pleasanton High School 8,605 54 Samuel -

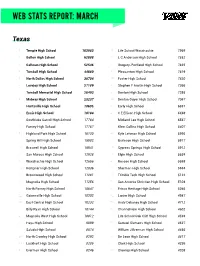

Web Stats Report: March

WEB STATS REPORT: MARCH Texas 1 Temple High School 163983 31 Life School Waxahachie 7969 2 Belton High School 62888 32 L C Anderson High School 7852 3 Calhoun High School 52546 33 Gregory-Portland High School 7835 4 Tomball High School 44880 34 Pleasanton High School 7619 5 North Dallas High School 38704 35 Foster High School 7420 6 Lovejoy High School 27189 36 Stephen F Austin High School 7366 7 Tomball Memorial High School 26493 37 Denton High School 7295 8 Midway High School 23237 38 Denton Guyer High School 7067 9 Huntsville High School 18605 39 Early High School 6881 10 Ennis High School 18184 40 C E Ellison High School 6698 11 Southlake Carroll High School 17784 41 Midland Lee High School 6567 12 Forney High School 17767 42 Klein Collins High School 6407 13 Highland Park High School 16130 43 Kyle Lehman High School 5995 14 Spring Hill High School 15982 44 Burleson High School 5917 15 Braswell High School 15941 45 Cypress Springs High School 5912 16 San Marcos High School 12928 46 Elgin High School 5634 17 Waxahachie High School 12656 47 Roscoe High School 5598 18 Kempner High School 12036 48 Sherman High School 5564 19 Brownwood High School 11281 49 Trimble Tech High School 5122 20 Magnolia High School 11256 50 San Antonio Christian High School 5104 21 North Forney High School 10647 51 Frisco Heritage High School 5046 22 Gainesville High School 10302 52 Lanier High School 4987 23 East Central High School 10232 53 Andy Dekaney High School 4712 24 Billy Ryan High School 10144 54 Channelview High School 4602 25 Magnolia West High School -

Future of Austin Avenue Bridges Comes Into Focus Transportation Experts Address Issue New Report Recommends ‘Destination’ Fix

Barber Kay McConaughey hangs up shares her story his She relished raising three sons, including clippers award-winning actor Page 1B Page 3B Vol. 40 No. 32 GEORGETOWN, TEXAS n JANUARY 11, 2015 One Dollar Future of Austin Avenue bridges comes into focus Transportation experts address issue New report recommends ‘destination’ fix By MATT LOESCHMAN session that precedes their 3 p.m. workshop. An independent Austin Av- the importance of increased assets,” said the report, which The workshop session will include rec- enue bridges assessment pre- pedestrian connectivity with was prepared by Cheney Bostic Two nationally prominent transporta- ommendations from the city’s Road Bond pared by Winter & Company, a the city’s award-winning San of Winter & Company. tion experts will talk about the future of the Committee, which has listed the Austin Av- Colorado urban design studio Gabriel River trails system, The plan would also: 75-year-old Austin Avenue bridges over the enue bridges as its top priority. with an international reputa- making the bridges safer for n Minimize construction north and south forks of the San Gabriel tion, offers clear recommenda- pedestrians and cyclists, using time to four to six months while River in a special meeting Tuesday. Public Q&A tions — and a very different ap- the bridge repair to turn the maintaining traffic on two The public is invited to the meeting, set Council members in attendance will not proach from a previous bridges historic downtown into a desti- lanes of the bridges, lessening for 2 p.m. in council chambers, 101 East Sev- ask questions following the presentation, study — to the city council re- nation attraction and maintain- the negative impact on down- enth Street. -

Monticello Celebrates Arbor Day 1B

Monticello celebrates UAM maintains conference lead Arbor Day with series win over Reddies 1B 1C ADVANCE-MONTICELLONIAN 75¢ WEDNESDAY, APRIL 4, 2018 SERVING DREW COUNTY SINCE 1870 Remains still unidentifi ed BY ASHLEY FOREMAN black male,” Gober stated. [email protected] As of press time, the remains have not be positively identifi ed. Last week, the Advance-Mon- “The Arkansas State Police has ticellonian reported that skeletal no evidence at this time to positive- remains had been found on Mon- ly identify the remains of the per- day, March 26 behind a home on son whose remains were discov- Arkansas Highway 138, east of ered earlier this week,” reiterated Monticello. Bill Sadler, ASP public informa- The Drew County Sheriff’s De- tion offi cer. “ASP/CID (Criminal partment arrived at the scene and Investigation Division) is working the investigation was turned over the investigation. Other than the to the Arkansas State Police. date and the location of remains According to Drew County discovery, there’s not much I can Sheriff Mark Gober, the skeletal tell you.” remains were sent to the state crime Check the Advance-Monticel- lab for DNA testing. lonian website, www.mymonticel- “It is believed at this time, that lonews.net, for the most up to date the remains belong to that of a information on this story. Internet photo REMEMBERING A LIFE CUT SHORT Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. waves to the crowd before delivering his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in A HELPING HAND Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Today marks the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination in Memphis, Tenn. -

TX-Schools (11)12 2 19

Affiliated Chapters December 2, 2019 Advisor First Advisor Chapter ID Name City HS/MS District Name Last Name 5445 CAST STEM High School San Antonio HS Alamo TEA - Region 20 James Quintana 959 Douglas Macarthur High School SAN ANTONIO HS Alamo TEA - Region 20 Jason Sandoval Edgewood STEAM Academy, Edgewood Independent School 5841 District San Antonio HS Alamo TEA - Region 20 Richard Huntoon Roosevelt Engineering & Tec 674 Academy San Antonio HS Alamo TEA - Region 20 Grizelda Gentry 3521 Samuel Clemens High School Schertz HS Alamo TEA - Region 20 Michelle Hendrick Assn. Houston Tech Ed - 2985 East Early College High School Houston HS Region 41 Sam N. Saenz Assn. Houston Tech Ed - 5963 Heights High School Houston HS Region 41 Nathaniel Hudgins Young Women's College Assn. Houston Tech Ed - 3674 Preparatory Academy Houston HS Region 41 Astra Zeno 3519 Arthur L. Davila Middle School Bryan MS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Nicole Debolt 5069 Bridgeland High School Cypress HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Josh Simmons 1049 Bryan High School Bryan HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Carl Walther 1129 Cy-Fair High School Cypress HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Andrew Parker 5237 Cypress Park High School cypress HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Rankin Morris 1841 Cypress Ranch High School Cypress HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Kristi Grove 632 Jersey Village High School Houston HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Doug Pearson 1575 Klein Collins High School Spring HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Nicholas Rodnicki 753 Klein High School Klein HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Joe White 612 Klein Oak High School Klein HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Loren Freed 117 Langham Creek HS Houston HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Eleazar Alanis 5955 Rudder High School Bryan HS Brazos Valley - Region 6 James Sciandra Affiliated Chapters December 2, 2019 2519 Smith Middle School Cypress MS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Kenny Koncaba 217 Spillane Middle School Cypress MS Brazos Valley - Region 6 Kevin Defreese 1045 Stephen F. -

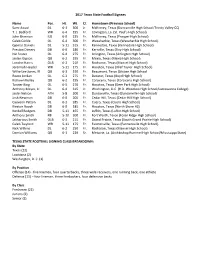

2017 Texas State Football Signees Name Pos. Ht. Wt. Cl. Hometown

2017 Texas State Football Signees Name Pos. Ht. Wt. Cl. Hometown (Previous School) Sami Awad DL 6-1 300 Jr. McKinney, Texas (Duncanville High School/Trinity Valley CC) T. J. Bedford WR 6-4 195 Fr. Covington, La. (St. Paul’s High School) John Brannon ILB 6-0 235 Fr. McKinney, Texas (Prosper High School) Caleb Carlile OL 6-4 300 Fr. Waxahachie, Texas (Waxahachie High School) Gjemar Daniels DL 5-11 315 Fr. Kennedale, Texas (Kennedale High School) Preston Dimery DB 6-0 180 Fr. Kerrville, Texas (Tivy High School) Nic Foster OL 6-4 275 Fr. Arlington, Texas (Arlington High School) Jaylen Gipson QB 6-2 195 Fr. Mexia, Texas (Mexia High School) London Harris OLB 6-2 210 Fr. Rosharon, Texas (Manvel High School) Jeremiah Haydel WR 5-11 175 Fr. Houston, Texas (Alief Taylor High School) Willie Lee Jones, III QB 6-3 190 Fr. Beaumont, Texas (Silsbee High School Reece Jordan OL 6-3 275 Fr. Decatur, Texas (Boyd High School) Kishawn Kelley QB 6-2 195 Fr. Corsicana, Texas (Corsicana High School) Tanner King OL 6-5 270 Fr. Houston, Texas (Deer Park High School) Anthony Mayes, Jr. OL 6-4 315 Jr. Washington, D.C. (H.D. Woodson High School/Lackawanna College) Jaylin Nelson ATH 5-8 200 Fr. Duncanville, Texas (Duncanville High School) Josh Newman DB 6-0 205 Fr. Cedar Hill, Texas (Cedar Hill High School) Caeveon Patton DL 6-2 285 Fr. Cuero, Texas (Cuero High School) Kieston Roach DB 6-0 185 Fr. Houston, Texas (North Shore HS) Kordell Rodgers DB 5-11 165 Fr.