“Well-Knownness” and the Right of Publicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Otay! - the Billy Buckwheat Thomas Story by William Thomas Otay! - the Billy Buckwheat Thomas Story

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Otay! - The Billy Buckwheat Thomas Story by William Thomas Otay! - The Billy Buckwheat Thomas Story. Hardback presentation version. William Thomas, the man known as "Buckwheat," one of the most beloved characters in the history of the Our Gang and Little Rascals films, rose from obscurity to become an American icon. Billy's heritage grew to be more than the ninety-three comedies in which he appeared as Buckwheat. He was a husband, father, and soldier. Several generations have come to know Buckwheat as if he was a real person, but few knew Billy, the man behind the myth. In "Otay!" The Billy "Buckwheat" Thomas Story, . Read More. Hardback presentation version. William Thomas, the man known as "Buckwheat," one of the most beloved characters in the history of the Our Gang and Little Rascals films, rose from obscurity to become an American icon. Billy's heritage grew to be more than the ninety-three comedies in which he appeared as Buckwheat. He was a husband, father, and soldier. Several generations have come to know Buckwheat as if he was a real person, but few knew Billy, the man behind the myth. In "Otay!" The Billy "Buckwheat" Thomas Story, William Thomas, Jr., Billy's son, joins with acclaimed author David W. Menefee to brush back the sands of time and unearth the facts beneath the fable. For the first time, the true story is told how producer Hal Roach, Sr. plucked three-year-old Billy from hundreds of children and raised him on a pedestal before an adoring public. -

Melton Barker and the Kidnappers Foil

Stream of History May 2011 Jackson County - Movies Melton Barker and “The Kidnappers Foil” © 2011 by Robert D. Craig 15650 State Highway A, Kennett, MO 63857 In mid-May 1938, Hollywood came calling on Jackson County. A fancy limousine with California license plates pulled off Highway 67 at Swifton into Buster Cheek’s service station. Out of the car came a round-faced little boy who, when asked his name, replied, “My name’s ‘Spanky,’ and I’m a movie actor.” No further information was required of him because every- one at that time knew who “Spanky” was. He was the famous George “Spanky” McFarland. He appeared in nearly one hundred “Our Gang” films from 1932-1942, and he performed in more than a dozen other shows dur- ing his career. During the 15 minutes his car was being serviced, “Spanky” visited with Mrs. Cheek. She commented that he “appeared to be a per- fectly normal boy, and used no trace of braggadocio in announcing that ‘he was a movie star.’ ” He was a typical boy, curious about things that little boys would find interesting around a service station in the 1930s. “Spanky” might have been surprised to know that less than 20 miles down that same highway, at Newport, there were 100 child movie stars (see listing on page 23). Although obviously they were not in the same league with “Spanky,” some may have thought they were. A movie they starred in had just played several weeks earlier at the Strand Theatre on Walnut Street. They were made stars by Melton Barker. -

Titan Sports, Inc. V. Hellwig: Wrestling with the Distinction Between Character and Performer

NOTES Titan Sports, Inc. v. Hellwig: Wrestling with the Distinction Between Character and Performer I. OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ 155 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................. 156 A. Character Protection .............................................................. 156 B. The Right to Exploit One’s Own Likeness and Name ............ 158 C. Association of Character and Performer ............................... 160 III. ANALYSIS .......................................................................................... 161 V. C ONCLUSION .................................................................................... 163 I. OVERVIEW This case presents issues regarding the border between the right of publicity and copyright protection. The defendant is a well-known professional wrestler. While his given name is James Hellwig (Hellwig), the name that he chose to live by professionally, and now legally, is “Warrior.” In 1987, Hellwig entered into his first contract with the plaintiff, better known as the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), to perform in wrestling shows.1 The contract provided that any distinctive and identifying indicia for the wrestler, which were developed by the WWF, would be their exclusive property.2 This would grant exclusive license to the WWF for the creation of any characters, names, costumes, themes or gimmicks used by the wrestler in his performance. Under this contract, Hellwig wrestled -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

The Right of Publicity and Autonomous Self-Definition, 67 U

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2005 The Right of Publicity and Autonomous Self- Definition Mark P. McKenna Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark P. McKenna, The Right of Publicity and Autonomous Self-Definition, 67 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 225 (2005-2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/600 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY AND AUTONOMOUS SELF- DEFINITION* Mark P. McKenna- Arnold Schwarzenegger recently sued a company that was marketing a machine gun-toting bobblehead doll made in his image.' Schwarzenegger claimed that the producer was free-riding on the value of his image, violating his right of publicity.2 But where the Terminator turned Governor of California saw an attempt to exploit his hard-earned reputation, others saw valuable political speech intended to parody Schwarzenegger.3 The case ultimately settled,4 but not before drawing attention to the breadth of the * 0 2005 Mark P. McKenna ([email protected]). ** Assistant Professor, Saint Louis University School of Law. I owe debts of gratitude to individuals far too numerous to identify here. But a few deserve special mention, particularly Liz Magill, Barb Armacost, Tom Nachbar, Jennifer Mnookin, and Curt Bradley, whom I thank for their thoughts on this project and for their encouragement. -

Persona¿Character Copyrights and Merger¿S Role in the Evolution of Entertainment Expressions

Emory Law Journal Volume 67 Issue 4 2018 Persona¿Character Copyrights and Merger¿s Role in the Evolution of Entertainment Expressions Sydney Altman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Sydney Altman, Persona¿Character Copyrights and Merger¿s Role in the Evolution of Entertainment Expressions, 67 Emory L. J. 735 (2018). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol67/iss4/2 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALTMAN_COMMENT GALLEYPROOFS 4/23/2018 12:22 PM PERSONA–CHARACTER COPYRIGHTS AND MERGER’S ROLE IN THE EVOLUTION OF ENTERTAINMENT EXPRESSIONS ABSTRACT Millions of people tuned in to Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report to learn about the state of our nation from the renowned satirical character, Stephen Colbert. Millions more tuned in to watch the same Stephen Colbert make his return on CBS’s The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. However, after his first television revival, Viacom quickly shut down any possible future return, claiming that it, not Stephen Colbert the actor, held the copyright to the character Stephen Colbert. While this is not the first time that an actor was ineligible to maintain control over a persona–character he crafted, this incident exposed that copyright law does not have a means of protecting characters who become a true extension of the living, breathing actor. -

A Film by Sean Baker

June Pictures presents A Cre Film & Freestyle Pictures Company Production The F lorida Project A film by Sean Baker www.JunePictures.com/project/the-florida-project/ Facebook: Facebook.com/TheFloridaProject Twitter: @theFLproject 112 minutes / USA / 2017 INTERNATIONAL PRESS IN CANNES: Liz Miller [email protected] Christelle Randall [email protected] Aneeka Verma [email protected] Cannes Office Tel : +33 4 93 39 26 75 The Florida Project PRODUCTION NOTES SYNOPSIS The Florida Project tells the story of Moonee, a precocious six-year- old and her ragtag group of friends. The children’s summer break is filled with wonder, mischief and adventure while the adults around them struggle with hard times. Throughout the United States, budget motels have become a last refuge for people who have found themselves unable to secure a permanent residence. A growing “hidden homeless” population, 41% of which is composed of families, struggles week to week in order to keep a roof over their heads. Our story takes place just outside of Orlando, the vacation capital of the world and home to “The Most Magical Place on Earth.” Along the main highway that runs through the land of theme parks and resorts, budget motels that once attracted tourists by exploiting the Disney mystique, now house homeless families. Moonee and her twenty-two year old mother, Halley, live at one such establishment — The Magic Castle Motel. The closest thing Moonee has to a father is Bobby, the motel’s manager, a guarded and diligent man who is taunted by the children’s antics. Halley has lost her job and a new girl the same age as Moonee has moved in at the motel next door - it's going to be an eventful summer. -

General Spanky

General Spanky US : 1936 : dir. Fred Newmeyer & Gordon Douglas : Hal Roach / M-G-M : 71 min prod: : scr: Richard Flournoy, Hal Yates & John Guedal : dir.ph.: Spanky McFarland; Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer; Billy “Buckwheat” Thomas; Rex Downing; Jerry Tucker ………….……………………………………….………………………………………… Phillips Holmes; Rosina Lawrence; Louise Beavers; Hobart Bosworth; Ralph Morgan; Irving Pichel Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 2552a 2.5 5 3 999 - - - - - No Unseen No expense spent - Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer (left) with the eponymous Spanky McFarland in their full military regalia. Source: The Moving Picture Boy Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide master may displease contemporary 1996 review: audiences. ** ” “Sluggish Civil War story, balancing kiddie antics against an adult romance, was Halliwell’s Film Guide review: intended to showcase three "Our Gang” stars in a feature film format; it's easy to “A small boy is instrumental in a famous see why there wasn't an encore. Civil War victory. Uneasy sentimental Buckwheat's role as a slave in search of a melodrama vehicle for one of the moppet stars [sic] of "Our Gang”. Scr: Richard From “FREE EATS“ in 1932 to Flournoy, Hal Yates & John Guedal.” “UNEXPECTED RICHES“ in 1942, Spanky was a top favourite in the Gang’s shorts. He “Desultory, overlong... built for the lesser was in 94 altogether, plus his own star vehicle, family trade” – Variety the full-length feature “GENERAL SPANKY“, in which he leads a Southern kids’ militia against a Union army. The The M.G.M. Story review: transplantation of the Gang into a historical setting with awkward overtones of real “"GENERAL SPANKY" incongruously bloodshed didn’t work, although Spanky, teamed the elegant Phillips Holmes with aided by “Alfalfa“ Switzer, “Buckwheat“ Spanky McFarland, the fat tot of "Our Gang", Thomas and other Gang stalwarts, is still a in a Civil War drama by Flournoy, Hal Yates formidable little pudding. -

January 16Th, 2010 Fred Bomar Collection Lot Description Price 9000

January 16th, 2010 Fred Bomar Collection Lot Description Price (lot of 90+) San Francisco 49ers slabbed sports cards, includes some with autographs, players include Steve Young, Joe Montana, Patrick Willis, Kevan Barlow, Terrell Owens, Frank Gore, Jerry Rice, cards include rookie 9000 cards, slabbed fabric patches, etc., note: worth inspection $ 400 (lot of 200+) American football slabbed sports cards, includes some with autographs and cards not graded, players include Antonio Freeman, Curtis Enis, Natrone Means, Doug Feute, Doug Staley, Neil Smith, Skip Hicks, Drew Bledsoe, Deion Sanders, Mark Brunell, Troy Aikman, cards include rookie cards, etc., note: worth 9001 inspection $ 225 (lot of 300+) American football slabbed sports cards, includes some with autographs and cards not graded, players include Eric Dickerson, Joey Porter, Barry Sanders, Maurice Clarett, Doug Flutie, Randall Cunningham, 9002 Matt Cassell, Matt Ryan, cards include rookie cards, etc., note: worth inspection $ 425 (lot of 25) Oakland Raiders football slabbed sports cards, includes some with autographs and cards not graded, players include Johnnie Lee Higgins, Gene Upshaw, Jamarcus Russell, Nnamdi Asomugha, Tim Brown, 9003 cards include rookie cards, etc., note: worth inspection $ 75 (lot of 50+) Basketball slabbed sports cards, includes some with autographs and cards not graded, players 9004 include Dennis Johnson, Joe Smith, Don MacLean, Bernard King, Clyde Drexler, etc., note: worth inspection $ 150 (lot of 30+) Baseball slabbed sports cards, the majority are the -

Untitled Review, New Yorker, September 19, 1938, N.P., and “Block-Heads,” Variety, August, 31, 1938, N.P., Block-Heads Clippings File, BRTC

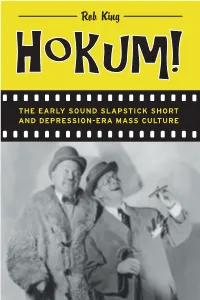

Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. Hokum! Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture Rob King UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2017 by Robert King This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: King, Rob. Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.28 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data King, Rob, 1975– author. Hokum! : the early sound slapstick short and Depression-era mass culture / Rob King. Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Indiana Law Journal Fame

Indiana Law Journal Volume 73 Issue 1 Article 1 Winter 1997 Fame Roberta Rosenthal Kwall DePaul University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Kwall, Roberta Rosenthal (1997) "Fame," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 73 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol73/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Famet ° ROBERTA ROSENTHAL KWALL INTRODUCTION Fame. I'm gonna live forever. I'm gonna learn how tofly. Ifeel it comin' together. People will see me and cry.' No country in the world is so driven by personality as is the United States. Fame is used to persuade, inspire, and inform Americans in nearly every aspect of their lives. As a group, Americans are fascinated not only with the concept of fame, but also with those who embody its essence. This fascination, while not uncommon in other countries, has reached epic proportions in the United States. Its impact on the legal system has spawned a legal doctrine, the right of publicity, whose primary function is to prevent the unauthorized commercial exploitation of celebrity personas. Since 1953, when the right of publicity first received explicit legal recognition, 4 courts, legislatures, and academicians have become increasingly interested in the doctrine's application and scope.