Sectarianism in New Zealand Rugby in the 1920S, in Ireland And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“They'll Go Like British Shells!”: a Historical Perspective on Commercial

“They’ll Go Like British Shells!”: A Historical Perspective on Commercial “Anzackery” in New Zealand STEVEN LOVERIDGE Abstract The term “Anzackery” was regularly employed in New Zealand during the centenary of the First World War to condemn a sense of irreverent exploitation of Anzac remembrance, with commercial exploitation forming a particular concern. This article contends that such sentiments continue a much older dynamic and seeks to offer a historical perspective by surveying the relationship between marketing and war, circa 1914–1918. It examines the rise of a distinctive mode of branding goods and services in the decades leading up to and including the First World War, investigates the wartime mobilisation of this consumerism and contemplates the nature of the resulting criticism. In doing so, it provides some perspective on and insight into the contemporary concerns of the relationship between commercial activity and Anzac remembrance in New Zealand. Across the centenary of the First World War, New Zealand enterprises displayed a remarkable capacity to brand diverse products with reference to the conflict and Anzac.1 Museum gift shops stocked a wealth of merchandise—including T-shirts, mobile phone cases, fridge magnets, stickers, coffee mugs, drink coasters and postcards—stamped with First World War iconography. Specialty remembrance poppies were produced for motorists to attach to their vehicles’ bumpers and rear windows. The Wellington Chocolate Factory created “The Great War Bar,” the wrapper of which depicted entrenched soldiers taking relief in small comforts. Accompanying marketing noted that “Thousands of chocolate bars left the hands of loved ones on their voyage to those on the front line. -

Coastal Hazards of the Dunedin City District

Coastal hazards of the Dunedin City District Review of Dunedin City District Plan—Natural Hazards Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN 978-0-478-37678-4 Report writers: Michael Goldsmith, Manager Natural Hazards Alex Sims, Natural Hazards Analyst Published June 2014 Cover image: Karitane and Waikouaiti Beach Coastal hazards of the Dunedin City District i Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Scope ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.3. Describing natural hazards in coastal communities .......................................................... 2 1.4. Mapping Natural Hazard Areas ........................................................................................ 5 1.5. Coastal hazard areas ...................................................................................................... 5 1.6. Uncertainty of mapped coastal hazard areas .................................................................. -

Rape Representation in New Zealand Newspapers (1975 – 2015)

It’s The Same Old Story: Rape Representation in New Zealand Newspapers (1975 – 2015) By Angela Millo Barton A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Criminology School of Social and Cultural Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2017 ii Abstract Newspaper reporting of rape, and in particular, representations of women as rape victims, have historically been presented by the media in a misinformed manner, influenced by myths and misconceptions about the dynamics of sexual violence. Previous research has shown media depictions can promote victim-blaming attitudes which affect society’s understanding toward sexual violence, promoting false narratives and rape-supportive beliefs. Victim narratives of sexual victimisation struggle within a ‘culture of silencing’ that prevents the majority of sexual offending from coming to the attention of authorities, and identifying the silencing of women’s experiences of rape has, and continues to be, a key objective for feminist scholars. Newspapers are one medium which has been exclusionary of women's experiences, therefore it is important to look at the role of newspapers on a longitudinal level to investigate whether there have been changes in reporting practices and attitudes. To address this issue, this study draws on feminist perspectives and adopts a quantitative and qualitative methodology utilising newspaper articles as a specific source of inquiry. Articles concerning male-female rape were collected from eight prominent New Zealand newspapers across a 40 year period from 1975 – 2015 with individual years for analysis being 1975, 1985, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Results from this analysis show minimal inclusion of women’s words regarding newspaper commentary in articles concerning rape. -

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps 1 Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops 2-3 Community Gardens 4 Community Orchards 5 Food Distribution Centres 6 Food Banks 7 Healthy Eating Services 8-9 Transport 10 Water Fountains 11 Food Foraging To view this information on an interactive map go to goo.gl/5LtUoN For further information contact Sophie Carty 03 477 1163 or [email protected] - INFORMATION UPDATED 07 / 2017 - WellSouth Primary Health Network HauoraW MatuaellSouth Ki Te Tonga Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga g f e a c b d Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops All Saints' Fruit & Veges Low cost fruit and vegetables ST LUKE’S ANGLICAN CHURCH ALL SAINTS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH a 67 Gordon Rd, Mosgiel 9024 e 786 Cumberland St, North Dunedin 9016 OPEN: Thu 12pm - 1pm and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 8.45am - 10am and 4pm - 6pm ANGLICAN CHURCH ST MARTIN’S b 1 Howden Street, Green Island, Dunedin 9018, f 194 North Rd, North East Valley, Dunedin 9010 OPEN: Thu 9.30am - 11am OPEN: Thu 4.30pm - 6pm CAVERSHAM PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH ST THOMAS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH c Sidey Hall, 61 Thorn St, Caversham, Dunedin 9012, g 1 Raleigh St, Liberton, Dunedin 9010, OPEN: Thu 10am -11am and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 5pm - 6pm HOLY CROSS CHURCH HALL d (Entrance off Bellona St) St Kilda, South Dunedin 9012 OPEN: Thu 4pm - 5.30pm * ORDER 1 WEEK IN ADVANCE WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga 1 g h f a e Community Gardens Land gardened collectively with the opportunity to exchange labour for produce. -

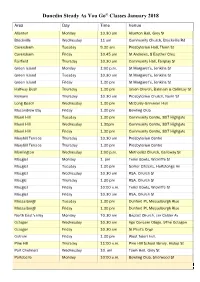

Dunedin Steady As You Go© Classes January 2018

Dunedin Steady As You Go© Classes January 2018 Area Day Time Venue Allanton Monday 10.30 am Allanton Hall, Grey St Brockville Wednesday 11 am Community Church, Brockville Rd Caversham Tuesday 9.30 am Presbyterian Hall, Thorn St Caversham Friday 10.45 am St Andrews, 8 Easther Cres Fairfield Thursday 10.30 am Community Hall, Fairplay St Green Island Monday 1:00 p.m. St Margaret’s, Jenkins St Green Island Tuesday 10.30 am St Margaret’s, Jenkins St Green Island Friday 1.30 pm St Margaret’s, Jenkins St Halfway Bush Thursday 1.30 pm Union Church, Balmain & Colinsay St Kaikorai Thursday 10.30 am Presbyterian Church, Nairn St Long Beach Wednesday 1.30 pm McCurdy-Grimman Hall Macandrew Bay Friday 1.30 pm Bowling Club Maori Hill Tuesday 1.30 pm Community Centre, 807 Highgate Maori Hill Wednesday 1.30pm Community Centre, 807 Highgate Maori Hill Friday 1.30 pm Community Centre, 807 Highgate Maryhill Terrace Thursday 10.30 am Presbyterian Centre Maryhill Terrace Thursday 1.30 pm Presbyterian Centre Mornington Wednesday 1:00 p.m. Methodist Church, Galloway St Mosgiel Monday 1. pm Tairei Bowls, Wickliffe St Mosgiel Tuesday 1.30 pm Senior Citizens, Hartstonge Av Mosgiel Wednesday 10.30 am RSA, Church St Mosgiel Thursday 1.30 pm RSA, Church St Mosgiel Friday 10:00 a.m. Tairei Bowls, Wickliffe St Mosgiel Friday 10.30 am RSA, Church St Musselburgh Tuesday 1.30 pm Dunford Pl, Musselburgh Rise Musselburgh Friday 1.30 pm Dunford Pl, Musselburgh Rise North East Valley Monday 10.30 am Baptist Church, cnr Calder Av Octagon Wednesday 10.30 am Age Concern Otago, 9The Octagon Octagon Friday 10.30 am St Paul’s Crypt Outram Friday 1.30 pm West Taieri hall, Pine Hill Thursday 11:00 a.m. -

Hymn of Hate”

Wicked Wilhelmites and Sauer Krauts: The New Zealand Reception of Ernst Lissauer’s “Hymn of Hate” ROGER SMITH Abstract When the German poet Ernst Lissauer published his anti-English poem “Haßgesang gegen England” in the early weeks of the First World War, the effect was electric. The poem, translated into English and dubbed the “Hymn of Hate,” echoed around the globe, reaching as far as New Zealand where newspapers sedulously followed its international reception and published local responses. Given the nature of New Zealand’s relationship to Britain and the strength of the international press links, it is not surprising that news of the poem reached New Zealand in the early months of the war. However, the sheer volume of coverage given to a single German war poem in New Zealand’s press over the course of the war and after, as well as the many and varied responses to that poem by New Zealanders both at home and serving overseas, are surprising. This article examines the broad range of responses to Lissauer’s now forgotten poem by New Zealanders during the Great War and after, from newspaper reports, editorials and cartoons, to poetic parodies, parliamentary speeches, enterprising musical performances and publications, and even seasonal greeting cards. “The poem fell like a shell into a munitions depot.” With these words, the Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig recalled the impact made by Ernst Lissauer’s anglophobic poem “Haßgesang gegen England” (“A Chant of Hate Against England”) upon first publication in Germany in 1914.1 The reception of Lissauer’s poem in the German-speaking world is a remarkable story, but its reception, in translation, in the English-speaking world is no less surprising. -

The Natural Hazards of South Dunedin

The Natural Hazards of South Dunedin July 2016 Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-908324-35-4 Report writers: Michael Goldsmith, ORC Natural Hazards Manager Sharon Hornblow, ORC Natural Hazards Analyst Reviewed by: Gavin Palmer, ORC Director Engineering, Hazards and Science External review by: David Barrell, Simon Cox, GNS Science, Dunedin Published July 2016 The natural hazards of South Dunedin iii Contents 1. Summary .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Environmental setting .......................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Geographical setting ............................................................................................................ 3 2.2. Geological and marine processes........................................................................................ 6 2.3. European land-filling ............................................................................................................ 9 2.4. Meteorological setting ........................................................................................................11 2.5. Hydrological -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

536 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 18 ¥ILTTARY DISTRICT No. 11 (DUNEDIN)--'-continue,l, MILITARY DISTRICT No, 11 (DUNEDIN)-aontinued. 291227, McCammon, John Alexander, station-manager, Becks, 420399 McLaughlan, James Campbell, warehouseman, 99 Cargill Louden Rural Delivery. St., Dunedin. 431328 McCloy, James Bernard; Gimmerburn, 263277 McLay, Andrew Forrester, cashier, 24 Black's Rd., Dunedin. 270769 McCormick, Lachlan Donald, artist, care of Government 390400 McLean, Bruce, 24 Gladstone Rd., Mosgiel. , , Deer Party, Gorge Station, via Omarama, Otago, 256815 McLean, Gavin John, 43 Norman St,, Anderson's Bay 232328 McCulloch, Charles James, concrete worker, 61 Royal Ores., Dunedin. Musselburgh, Dunedin. 277478 McLean, James William, farm hand, Island Cliff, Rural 282516 McCullough, Neville Watson, joiner, 61 Royal Ores., Mussel Delivery, Oamaru. burgh, Dunedin. ,106252 McLean, John Stewart, farm hand, 150 Five Forks, Oamaril. 420737 McCutcheon, William James Walker, stores labourer, 43 ,041992 McLellan, Arthur William, dental student, 28 Elliott' St., }felena St., Dunedin 8.W. 1. Anderson's Bay, Dunedin. 237016 MacDonald, Allan Gordon, electrician, 5 Preston Ores., 253789 McLennan, John William, labourer, Kokoamo, Waitaki. , Belleknowes, Dunedin. _262314 McLeod, Alexander Ross, labourer, Glenpark Rural Delivery,, 275131 McDonald, Burnett Sutherland, fruit-farmer, Outram. Palmerston. 131242 McDonald, Gordon ,Alexander, machine-worker, 117 Forth 234524 McLeod, Charles Graham, builder, 84 Gordon Rd., Mosgiel., St., Dunedin. 281396 Macleod, Edwin Benjamin, carpenter, 37 Queen St., Dunedin.. 376321 McDonald, Graeme Comrie, coal-miner, Brighton Rd., 255954 MacLeod, William; labourer, 27 Ribble St., Oamaru. , , Fairfield, Otago. 235584 McLeod, William, linotype-operator, 5 Stour St., Oamaru. 275218 Macdonald, _Ian, apprentice engineer, 8 Lawrence St., ,250739 McLeod, William James, farm hand, Peebles. -

The Perils of Impurity

New Zealand Journal of History, 49, 2 (2015) The Perils of Impurity THE NEW ZEALAND PURITY CRUSADES OF HENRY BLIGH, 1902–19301 AMONG THE CYCLES of sexual expression and repression identified by historians such as Lawrence Stone, Jeffrey Weeks and Richard Davenport- Hines, the three decades prior to the First World War stand out as a time of particular anxiety over sexual expression in young males.2 One manifestation of this concern was the proliferation of purity movements in Britain and the Empire. While the British movements have received considerable scholarly attention, there has been comparatively little study of the purity movement in New Zealand, and as yet no comprehensive account.3 An important influence on the New Zealand purity and hygiene movements was the Australian White Cross League (AWCL), for which extant documentation is quite rare. Although AWCL lecturer Henry Bligh is not a figure known to history, there has been some acknowledgement of his New Zealand crusades, his milieu and the social and ideological conditions that made them possible. Educational historian Colin McGeorge refers to the AWCL in his insightful discussion of ‘Sex Education in 1912’, concluding that it was impossible to ‘determine the extent’ of the League’s lecturer’s New Zealand operations.4 Stevan Eldred-Grigg mentions the AWCL as one of a number of short-lived New Zealand purity organizations.5 Chris Brickell focuses on the inconsequential role played by the AWCL in the 1924 Inquiry into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders and briefly on Bligh’s visits to New Zealand schools.6 In this article I discuss the rise of two sex education factions: social purity and social hygiene. -

12. New Zealand War Correspondence Before 1915

12. New Zealand war correspondence before 1915 ABSTRACT Little research has been published on New Zealand war correspondence but an assertion has been made in a reputable military book that the country has not established a strong tradition in this genre. To test this claim, the author has made a preliminary examination of war correspondence prior to 1915 (when New Zealand's first official war correspondent was appointed) to throw some light on its early development. Because there is little existing research in this area much of the information for this study comes from contemporary newspaper reports. In the years before the appointment of Malcolm Ross as the nation's official war correspondent. New Zealand newspapers clearly saw the importance of reporting on war, whether within the country or abroad and not always when it involved New Zealand troops. Despite the heavy cost to newspapers, joumalists were sent around the country and overseas to cover confiiets. Two types of war correspondent are observable in those early years—the soldier joumalist and the ordinary joumalist plucked from his newsroom or from his freelance work. In both cases one could call them amateur war correspondents. Keywords: conflict reporting, freelance joumaiism, war correspondents, war reporting ALLISON OOSTERMAN AUT University, Auckland HIS ARTICLE is a brief introduction to New Zealand war correspondence prior to 1915 when the first official war correspon- Tdent was appointed by the govemment. The aim was to conduct a preliminary exploration ofthe suggestion, made in The Oxford Companion to New Zealand military history (hereafter The Oxford Companion), that New Zealand has not established a strong tradition of war correspondence (McGibbon, 2000, p. -

APRIL 2019.Pub

Number 321 APRIL 2019 Published at 47 Wickliffe Tce, Port Chalmers Futomaki Restaurant Port Chalmers It's official! Port Chalmers has a new restaurant situated in the former Savings Bank/ Rowan Bishop Catering building on George Street, next door to the Port Chalmers Police Station. The owners, Mercel and Alquen Duran opened Futomaki, a Filipino-Japanese restaurant, on the 1st of March 2019. They started in South Dunedin a couple of years back, but they had originally been eyeing the Port Chalmers location. Now that it has finally become a reality, they gave up the store in South Dunedin to put all of their focus into their new location. Back in 2012, the couple was looking for something new, and started to look at Port Chalmers. The following year they discovered that the building that now houses the res- taurant was vacant. By that time, they were already seriously considering the idea of starting their restaurant business there. After successfully locating the owner and coming to an agreement, they began developing the plans for the restaurant, working with the council on the improvement of the interior of the building - all while operating their store in South Dunedin. Mercel tells The Rothesay News that being able to finally realize their dream was scary at first. However, all of the worries were quickly dispelled by the immense support of the community. She says that the response has been nothing but amazing, with ex- cellent reviews and feedback from people and through social media. While the menu is already extensive as it is, they plan to add more to it like sushi, coffee, and more beverage options, so there will be more to choose from and more reasons for everyone to come back. -

The South Dunedin Coastal Aquifer & Effect of Sea Level Fluctuations

The South Dunedin Coastal Aquifer & Effect of Sea Level Fluctuations Prepared by Jens Rekker, Resource Science Unit, ORC Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, 70 Stafford St, Dunedin 9054 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN 978-0-478-37648-7 Published October 2012 Prepared by Jens Rekker, Resource Science Unit Sea Level Effects Modelling for South Dunedin Aquifer i Overview Background South Dunedin urban area, which is mainly residential, is generally low lying reclaimed land, having once been coastal dunes and marshes. The underlying area has a groundwater system (or coastal aquifer) with a water table very close to the surface. The water table is closely tied to the surrounding sea level at both the ocean and harbour margins. The Otago Regional Council has been monitoring groundwater levels at three bores since 2009; results from which indicate that water table height is under the direct influence of climate and mean sea level, plus the drainage provided by the area’s storm and wastewater drains. The low lying land and already high water table makes the area vulnerable to any future rises in sea level. If the water table did rise any further it would create further pressure on the current drainage system and also increase the chances of surface ponding. Groundwater modeling was used in this investigation to assess the effects of a range of different sea level rise scenarios.