The Walking Dead As Post-Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interactions of Patagonian Toothfish Fisheries With

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 17 (2010): 179–195 INTERACTIONS OF PATAGONIAN TOOTHFISH FISHERIES WITH KILLER AND SPERM WHALES IN THE CROZET ISLANDS EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE: AN ASSESSMENT OF DEPREDATION LEVELS AND INSIGHTS ON POSSIBLE MITIGATION STRATEGIES P. Tixier1, N. Gasco2, G. Duhamel2, M. Viviant1, M. Authier1 and C. Guinet1 1 Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé CNRS, UPR 1934 Villiers-en-Bois, 79360 France Email – [email protected] 2 MNHN Paris, 75005 France Abstract Within the Crozet Islands Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) longline fishery is exposed to high levels of depredation by killer (Orcinus orca) and sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). From 2003 to 2008, sperm whales alone, killer whales alone, and the two species co-occurring were observed on 32.6%, 18.6% and 23.4% respectively of the 4 289 hauled lines. It was estimated that a total of 571 tonnes (€4.8 million) of Patagonian toothfish were lost due to depredation by killer whales and both killer and sperm whales. Killer whales were found to be responsible for the largest part of this loss (>75%), while sperm whales had a lower impact (>25%). Photo-identification data revealed 35 killer whales belonging to four different pods were involved in 81.3% of the interactions. Significant variations of interaction rates with killer whales were detected between vessels suggesting the influence of operational factors on depredation. When killer whales were absent at the beginning of the line hauling process, short lines (<5 000 m) provided higher yield and were significantly less impacted by depredation than longer lines. -

The Iron Fist Vs. the Microchip

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 5 Number 2 Volume 5, No. 2: Summer Article 6 2012 The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip Elizabeth I. Bryant Georgetown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 1-26 Recommended Citation Bryant, Elizabeth I.. "The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip." Journal of Strategic Security 5, no. 2 (2012) : 1-26. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.5.2.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip Abstract This article focuses on how information and communication technology (ICT) influences the behavior of authoritarian regimes. Modern information and communication tools can challenge authoritarian rule, but the same technology can be used by savvy regimes to buttress their own interests. The relationship of technology and political power is more accurately conceived of as a contested space in which competitors vie for dominance and as a neutral tool that is blind to value judgments of good versus evil. A realist understanding of the nature and limits of technology is vital in order to truly evaluate how ICT impacts the relative strength of intransigent regimes fighting to stay in power and those on the disadvantaged side of power agitating for change. -

Emily Kinney

Tktktktktktktkt | TKTKTKTKTKTKTKTKT Real StyleAUGUST 2018 FL WER POWER FASHION HOT HANDBAGS AND LATEST BEAUTY SINGER & TRENDS THE WALKING DEAD ALUM EMILY KINNEY WENDY PLUS! MESLEY HOW TO THROW CLAUDIA THE PERFECT DEY END-OF-SUMMER PARTY PHOTOS, LEFT: TKTKTKTKTK, RIGHT: TKTKTKTKTKT TKTKTKTKTKT TKTKTKTKTK, RIGHT: PHOTOS, LEFT: 1 Real Style August 2018 OH, EMILY THE WALKING DEAD STAR IS OUT WITH A NEW ALBUM AND SHOW. BY RODERICK THEDORFF AT FIRST GLANCE, YOU MIGHT with you and your family.’ I’m like ‘Oh THINK THAT Emily Kinney is one of yeah, that sounds awesome.’ So I sing those actresses that might not get no- that song in the third season, and then it ticed. After all when she first appeared on sort of became a thing.” The Walking Dead in season two as Beth Singing was as important aspect of Greene she wasn’t much more than a bit Kinney’s character, because it helped player on a big TV series. As the show Beth come out of her shy, introverted progressed though her role slowly grew, shell. “It became a way to sort of iden- and after two seasons of playing the part tify that character,” Kinney said. “Since she finally became a series regular. Her there were so many characters on The character became an essential part of the Walking Dead, I wasn’t always going to team, but it was more than her zombie be featured. It’s a device to almost make fighting skills that got her noticed. It was you feel like you know that character and her ability to sing. -

USCCB Prayers a Rosary for Life: the Sorrowful Mysteries

USCCB Prayers A Rosary for Life: The Sorrowful Mysteries The following meditations on the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary are offered as a prayer for all life, from conception to natural death. The First Sorrowful Mystery The Agony in the Garden Prayer Intention: For all who are suffering from abandonment or neglect, that compassionate individuals will come forward to offer them comfort and aid. Jesus comes with his disciples to the garden of Gethsemane and prays to be delivered from his Passion, but most of all, to do the Father's will. Let us pray that Christ might hear the prayers of all who suffer from the culture of death, and that he might deliver them from the hands of their persecutors. Our Father... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: hear the cries of innocent children taken from their mothers' wombs and pray for us sinners now, and at the hour of our death. Amen. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: soothe the aching hearts of those afraid to welcome their child. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: guide the heart of the frightened unwed mother who turns to you. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: move the hearts of legislators to defend life from conception to natural death. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: be with us when pain causes us to forget the inherent value of all human life. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: pray for the children who have forgotten their elderly parents. -

Story of Andree Trip Is

TTO yW»}ATHIPB— ^ • B o re ^ by'o. S. W*«Ui«r BawiWf . _ , ■'i->-^*'-Lf. v-*^ .■NEt=-wW»s.WJN.. -■■I'': r -- m '■ - - t — t ; w « vv—C aniD. EEurtfoitl. ' ■ >- r -'ATiacA.isB oaiinr‘‘CinMroii«^^ ' -'ter tlio M9Bth of Ai«iirt,‘lM6 \ Secretary Hyde Says Russia Governs French smd Dry Agents Had Raided Jer T IS^S MADE FRIENDS Happily — Were Divided WITH THE PHOTOGRAPHEKvl France Also is Hit by S to m ; Caus^ latest Price De TO SERV£ SENTENCE sey Plant When Gang Ap Sqn Francisco, , Sept. 20, Crews of Small Boats Res pression by Speculating by Race, Language and (A P )—Dr. Arthur C. Pillsbury, pears — Agents Are Dis Berkeley scientist, returning yes terday from the South Seas, cuer-False Rumor Si^s • on Chicago Exchange. Red Leader Who is in Russia Religion. where he donned a diver’s uni armed, One is Shot. form and photographed much Says He WiU Not Go Back 1 submarine life, told this one: That Big Cnnarder is k Washington, Sept. 20.— (A P.)— Geneva, Sept. 20.,— (A P.)—Cana 1 “Beautiful fish made friends 1 with me. ’ So great was their The Russi^ governnient stood Elizabeth, N. J., Sept. 20— (AP) da was held up before the League Peril— Much Damage R ^ On His Friends. Federal, State and local authorities curiosity that they gathered in charged today by Secretary Hyde of Nations Assembly today, as _ a hordes so’ L could not see to do wth partial responsibility for the sought today to round up a gang of shining example to peoples who are iny work, i would have to brush ported in Coast Towns. -

6 Pm 6:30 7 Pm 7:30 8 Pm 8:30 9 Pm 9:30 10 Pm 10:30

EC DT DN 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2 - - WHWC Elizabeth I (TVPG) Victoria on Masterpiece Victoria on Masterpiece (N) Queen Elizabeth I Antiques Roadshow (TVG) Austin City Limits (HD) The Simp- Bob’s Burg- Rent A live musical about struggling artists. (Live) (N) (HD) Fox25/48 Graham (:05) The Big (:35) To Be 3 - 25 WEUX sons (HD) ers (HD) News at 9 Bensinger Bang Theory Announced FOX-48 - - - WCCO-4 60 Minutes (N) (HD) Big Brother: Celebrity NCIS: Los Angeles (HD) Madam Secretary (HD) News News Joel Osteen Turning Point - - - WSTP-5 Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank (N) (HD) (:01) Shark Tank (N) (HD) 5 Eyewitness News at 10 On the Road Bensinger - - - WSAW-7 60 Minutes (N) (HD) Big Brother: Celebrity NCIS: Los Angeles (HD) Madam Secretary (HD) News 7 at 10 (:35) Face the Nation (N) NCIS: N.O. - - - KARE-11 The Titan Games The Titan Games American Ninja Warrior Team USA takes on the world. News Minn. Bound (:05) Entertainment Tonight 6 - - WKBTDT Entertainment Tonight (N) Dateline (TV14) (HD) NCIS: New Orleans (HD) Leverage “The Studio Job” Major Crimes (TV14) The Listener (TV14) (HD) 60 Minutes (TVPG) (N) Big Brother: Celebrity NCIS: Los Angeles A terror- Madam Secretary “Proxy News 8 at (:35) The James (:35) Wipeout 7 8 8 WKBT (HD) Edition (TVPG) (N) (HD) ist cell must be located. (N) War” (TVPG) (N) (HD) Ten (HD) M*A*S*H Brown Show “Feed Jill” CBS-8 - - - WAOW-9 Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank (N) (HD) (:01) Shark Tank (N) (HD) News 9 (:35) Entertainment Tonight Badgers America’s Funniest Home America’s Funniest Home Shark Tank A product for (:01) Shark Tank (TVPG) News 18 (:35) Castle Beckett’s ex- (:35) Castle 9 - 18 WQOW Videos (TVPG) (HD) Videos (TVPG) (N) (HD) traveling with pets. -

Festival at a Glance

FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE WEDNESDAY 22 10:00-11:00 BREAK 11:30-12:30 BREAK 14:00-15:00 BREAK 15:45-16:45 BREAK 17:45-18:30 18:30-21:00 P Masterclass: 11:00-11:30 P Meet the Controllers: 12:30-14:00 F Gamechanger: 15:00-15:45 P Edinburgh Does 16:45-17:45 L MacTaggart Lecture: Free coaches to The FH Screening: Love Island T Channel 4 Charlotte Moore, L It’s all about me... SA Music from Nancy Daniels, T How to Cash In Catchphrase with B Branded Michaela Coel Museum of Scotland Vanity Fair, ITV. S Meet the Controller: Random Acts Live Pitch BBC One on TV: Joanna Lumley Hannah Haynes, Discovery on the Streaming Roy Walker Entertainment Network depart from the EICC Exclusive Preview Damian Kavanagh, 11:00 - 12:00 F Tomorrow’s World with Clive Tulloh Harpist and Composer S Meet the Controller: Goldrush S Meet the Cocktail Reception 18:30 - 19:15 of Episode One with BBC Three SA Music from of TV 12:45 - 13:45 Zai Bennett, Sky UK 15:10 -15:40 Controllers: Richard 16:45 - 17:35 Cast & Crew Q&A 19:00 - 20:30 MK Too Posh Hannah Haynes, S The Insider’s Guide T Meet the Canadians: MK Commissioner LF Lightning Talk: Watsham, Hilary Rosen BT Pre-MacTaggart & Steve North, UKTV to Produce? Harpist and Composer to Building Your Opportunities for Interview: Luke Hyams, How to make a Lecture Drinks A+E Networks Opening UK Producers Green Production 16:45 - 17:35 P5 Speed Meetings: Audience on YouTube Head of Originals, MK Introductory Night Reception: The 12:45 - 13:30 15:10 - 15:40 10:00 - 16:00 MK Lessons from YouTube EMEA Address: SA Join us for a Museum of -

LLT 180 Lecture 22 1 Today We're Gonna Pick up with Gottfried Von Strassburg. As Most of You Already Know, and It's Been Alle

LLT 180 Lecture 22 1 Today we're gonna pick up with Gottfried von Strassburg. As most of you already know, and it's been alleged and I readily admit, that I'm an occasional attention slut. Obviously, otherwise, I wouldn't permit it to be recorded for TV. And, you know, if you pick up your Standard today, it always surprises me -- actually, if you live in Springfield, you might have met me before without realizing it. I like to cook and a colleague in the department -- his wife's an editor for the Springfield paper and she also writes a weekly column for the "Home" section. And so he and I were talking about pans one day and I was, you know, saying, "Well," you know, "so many people fail to cook because they don't have the perfect pan." And she was wanting to write an article about pans. She'd been trying to convince him to buy better pans. And so she said, "Hey, would you pose for a picture with pans? I'm writing this article." And so I said, "Oh, what the heck." And so she came over and took this photo. And a couple of weeks later, I opened Sunday morning's paper -- 'cause I knew it was gonna be in that week -- and went over to the "Home" section. And there was this color photo, about this big, and I went, "Oh, crap," you know. So whatever. Gottfried. Again, as they tell you here, we don't know much about these people, and this is really about love. -

Going Home After Your Heart Surgery

Going home after your heart surgery Contents ♥ Introduction 3 ♥ Before you leave the ward 4 ♥ Your journey home 5 ♥ Home sweet home Emotional reactions 6 Wound care and healing 7 Shortness of breath/swollen ankles 8 Hallucinations and dreams 9 Sleeping patterns/constipation 10 Healthy eating 11 Aches and pain 12 Stretches 13 ♥ Activity, exercise and rest Why exercise? 14 Guidelines for walking 15 How should I feel during exercise? 16 Getting active/rest 18 ♥ Returning to everyday activities Lifting and domestic activities 19 Sexual activity 20 Driving 21 Return to work 21 Travel abroad 22 ♥ Cardiac rehabilitation 23 ♥ Exercise diary 25 ♥ Support and advice 27 ♥ Further information 28 2 Introduction Although you will be given advice about your recovery during your stay in hospital, it may be difficult for you to remember everything. We hope this booklet will help. Please take time to read it before you leave and feel free to ask the nurses or physiotherapist any questions you may have. We know that for many patients going home after their heart operation can be a great relief, but it can also be quite daunting. Remember you are not alone. The cardiac rehabilitation nurses at Guy’s and St Thomas’ can support you and your family. You can contact them on 020 7188 0946. They work Monday to Friday, between 9am and 5pm. If they are unable to answer your call or you ring outside these hours, please leave your name and number on the answering machine and you will be contacted as soon as possible. You can also contact the cardiac rehabilitation physiotherapist if you have questions about physical activity and exercise. -

Portland Daily Press: March 23,1886

DAILY PRESS. PORTLANDI. lil, f ——■—^ Libtnry CENTS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862—VOL. 23. PORTLAND, TUESDAY MORNING, MARCH 23, 1886. M.M PRICE THREE Mr» John D. Tilton of Hill has GORHAM. SPECIAL NOTICES. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, FROM WASHINGTON. BROADWAY SURFACE FRAUDS. THE PAN ELECTRIC. FOREIGN. Rocky rented the farm of Simon Mayberry In this Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the A Day of Interest with the COMPANY, March 22.—The examina- village, and will establish a milk route. Stephen- INSURANCE. PORTLAND PUBLISHING Mr. to be Washikotox, Germans and Jews Expelled from Dunn's Free Iron Ships Bill Alderman Jaehne Arraigned and of Dr. sons nnd AT 97 Exchange Street. Portlajtd, Me. tion of Casey Young was resumed beforo Memorial services on the death Descendants of the Long- Reported to the House. Held In Poland. Cross W.D. Address aB communications to sas.OOO. the telephone Investigating committee this Morgan, a high official in the Golden fellow Family. LITTLE & PORTLAND PUBLISHING OO. after the will soon be held the members of CO., afternoon. Young said that first order, by the kind 31 Through Invitation of Mr. Ste- EXCHANGE Mr. a directors of the An Conflict Between Troops the in this and Cumberland STREET, Dingley Wants the Free Material! How Public Spirited Woman Se* meeting of the board of Pan Open Commandery L. of KHiablishetl iu 1M.J. THE WEATHER. phen Stephenson Gorham, the writer Section a Bill. cured Electric when It had been agreed and Miners In Belgium. Mills village. Rsllable Insurance Reported in Separate Jaehne’s Confession. Company, Rioting was privileged to visit the old farm house against Flro or in first sold on Mr. -

Lessons from Japan: Resilience After Tokyo and Fukushima

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 6 Number 2 Volume 6, No. 2: Summer Article 6 2013 Lessons from Japan: Resilience after Tokyo and Fukushima Michelle L. Spencer MLSK Associates LLC, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 70-79 Recommended Citation Spencer, Michelle L.. "Lessons from Japan: Resilience after Tokyo and Fukushima." Journal of Strategic Security 6, no. 2 (2013) : 70-79. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.6.2.6 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol6/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lessons from Japan: Resilience after Tokyo and Fukushima Abstract In the spring of 1995 Japan experienced the world’s first major terrorist attack using chemical weapons by a little-known religious cult called Aum Shinrikyo. The attack on the Tokyo subway, which killed 13 people, was the first lethal case of a non-state actor using a chemical agent against a civilian population. In March 2011, following a 9.0 magnitude earthquake in Japan, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor experienced a full meltdown releasing radiation into the surrounding area. The seemingly unhurried government reaction provided conflicting information to Japanese citizens, slowing evacuation and protective actions. Government failure is cited as a significant factor in the severity of the nuclear disaster in three investigations conducted after the incident. -

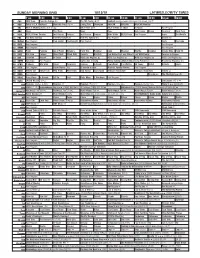

Sunday Morning Grid 10/13/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/13/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Saving Pets Champion NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Monster 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Hearts of Rock-Park 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jentzen Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb REAL-Diego Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Seaver (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Cooking Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Mixed Nutz Mixed Nutz Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Fascism in Europe 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como dice el dicho Por tu maldito amor (1990) Vicente Fernández.