Policy Brief: Producing and Promoting More Food Products Consistent With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1)In Bold Text, Knowledge and Skill Statement

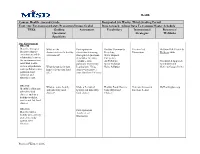

Health Course: Health - Second Grade Designated Six Weeks: Third Grading Period Unit: Our Environment/Safety/Prevention/Drugs/Alcohol Days to teach: Adjust Days To Campus Master Schedule TEKS Guiding Assessment Vocabulary Instructional Resources/ Questions/ Strategies Weblinks Specificity Our Environment HE.2.5B Describe strategies What are the Participation in Healthy Community Teacher-Led McGraw Hill: Health & for protecting the characteristics of a healthy discussion stemming Recycling Discussions Wellness 2006 environment and the environment? from guided questions. Water disposal relationship between (Examples: Wearing Emergency the environment and earbuds – noise Air Pollution Coordinated Approach individual health, pollution; minimizing Water Pollution To Child Health such as air pollution, What do you do in your hearing loss; Using Noise Pollution (Refer to Google Drive) water pollution, noise home to keep your food sunscreen to protect pollution, land safe? your skin from UV rays) pollution and ultraviolet rays. HE.2.1D What are some healthy Make a T-chart of Healthy Food Choices Generate discussion MyHealthyplate.org Identify healthy and and unhealthy food healthy and unhealthy Unhealthy Food based on T-chart unhealthy food choices? food choices Choices choices, such as a healthy breakfast, snacks and fast food choices. HE.2.1G Participation in Describe how a Teacher-Led healthy diet can help Discussion. protect the body against some diseases. Revised Winter 2016 Health Course: Health - Second Grade Designated Six Weeks: Third -

The Mayo Prescription for Good Nutrition

A PUBLICATION OF THE WELLNESS COUNCIL OF AMERICA EATING WELL: THE MAYO PRESCRIPTION FOR GOOD NUTRITION AN EXPERT INTERVIEW WITH DR. DONALD HENSRUD WELCOA.ORG EXPERT INTERVIEW EATING WELL: THE MAYO PRESCRIPTION FOR GOOD NUTRITION with DR. DONALD HENSRUD ABOUT DONALD HENSRUD, MD , MPH Dr. Hensrud is an associate professor of preventive medicine and nutrition in Mayo’s Graduate School of Medicine and the medical director for the Mayo Clinic Healthy Living Program. A specialist in nutrition and weight management, Dr. Hensrud served as editor in chief for the best-selling book The Mayo Clinic Diet and helped publish two award- winning Mayo Clinic cookbooks. ABOUT RYAN PICARELLA, MS , SPHR As President of WELCOA, Ryan works with communities and organizations around the country to ignite social movements that will improve the lives of all working people in America and around the world. With a deep interest in culture and sociology, Ryan approaches initiatives from a holistic perspective that recognizes the many paths to well- being that must be in alignment for long-term healthy lifestyle behavior change. Ryan brings immense knowledge and insight to WELCOA from his background in psychology and a career that spans human resources, organizational development and wellness program and product design. Prior to joining WELCOA, Ryan managed the award winning BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee (BCBST) Well@Work employee wellness program, a 2012 C. Everett Koop honorable mention awardee. Since relocating to Nebraska, Ryan has enjoyed an active role in the community, currently serving on the Board for the Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition in Omaha. Ryan has a Master of Science in Industrial and Organizational Psychology from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and a Bachelor of Science in Psychology from Northern Arizona University. -

Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention Or Maintenance of Diseases? Malia K

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Department of Kinesiology and Allied Health Projects Fall 11-14-2018 Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention or Maintenance of Diseases? Malia K. Burkholder Cedarville University, [email protected] Danae A. Fields Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ kinesiology_and_allied_health_senior_projects Part of the Kinesiology Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Burkholder, Malia K. and Fields, Danae A., "Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention or Maintenance of Diseases?" (2018). Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Projects. 6. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/kinesiology_and_allied_health_senior_projects/6 This Senior Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: THE VEGAN DIET AND DISEASES Does a vegan diet contribute to prevention or maintenance of diseases? Malia Burkholder Danae Fields Cedarville University THE VEGAN DIET AND DISEASES 2 Does a vegan diet contribute to prevention or maintenance of diseases? What is the Vegan Diet? The idea of following a vegan diet for better health has been a debated topic for years. Vegan diets have been rising in popularity the past decade or so. Many movie stars and singers have joined the vegan movement. As a result, more and more research has been conducted on the benefits of a vegan diet. In this article we will look at how a vegan diet may contribute to prevention or maintenance of certain diseases such as cancer, diabetes, weight loss, gastrointestinal issues, and heart disease. -

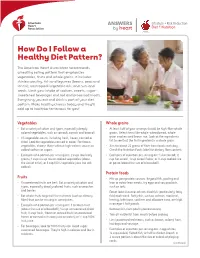

How Do I Follow a Healthy Diet Pattern?

ANSWERS Lifestyle + Risk Reduction by heart Diet + Nutrition How Do I Follow a Healthy Diet Pattern? The American Heart Association recommends a healthy eating pattern that emphasizes vegetables, fruits and whole grains. It includes skinless poultry, fish and legumes (beans, peas and lentils); nontropical vegetable oils; and nuts and seeds. Limit your intake of sodium, sweets, sugar- sweetened beverages and red and processed meats. Everything you eat and drink is part of your diet pattern. Make healthy choices today and they’ll add up to healthier tomorrows for you! Vegetables Whole grains • Eat a variety of colors and types, especially deeply • At least half of your servings should be high-fiber whole colored vegetables, such as spinach, carrots and broccoli. grains. Select items like whole-wheat bread, whole- • All vegetables count, including fresh, frozen, canned or grain crackers and brown rice. Look at the ingredients dried. Look for vegetables canned in water. For frozen list to see that the first ingredient is a whole grain. vegetables, choose those without high-calorie sauces or • Aim for about 25 grams of fiber from foods each day. added sodium or sugars. Check the Nutrition Facts label for dietary fiber content. • Examples of a portion per serving are: 2 cups raw leafy • Examples of a portion per serving are: 1 slice bread; ½ greens; 1 cup cut-up raw or cooked vegetables (about cup hot cereal; 1 cup cereal flakes; or ½ cup cooked rice the size of a fist); or 1 cup 100% vegetable juice (no salt or pasta (about the size of a baseball). -

Mediterranean Diet Food: Strategies to Preserve a Healthy Tradition

imental er Fo p o x d E C Journal of Experimental Food f h o e l m a n i Boskou, J Exp Food Chem 2016, 1:1 s r t u r y o J Chemistry DOI: 10.4172/2472-0542.1000104 ISSN: 2472-0542 Review Article open access Mediterranean Diet Food: Strategies to Preserve a Healthy Tradition Dimitrios Boskou* Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece *Corresponding author: Dimitrios Boskou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, Tel: +30 2310997791; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: September 21, 2015; Accepted date: November 28, 2015; Published date: December 7, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Boskou D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The traditional Mediterranean diet refers to a dietary pattern found in olive growing areas of the Mediterranean region. It’s essential characteristic is the consumption of virgin olive oil, vegetables, fresh fruits, grains, pasta, bread, olives, pulses, nuts and seeds. Moderate amounts of fish, poultry, dairy products and eggs are consumed with small amounts of red meat and wine. Over the past few decades there has been a growing interest in the role of the Mediterranean diet in preventing the development of certain diseases, especially cardiovascular disease. Mediterranean food products are now re-evaluated for the beneficial health effects in relation to the presence of bioactive compounds. The body of science unraveling the role of bioactives such as phenolic acids, various polyphenols, flavonoids, lignans, hydroxyl-isochromans, olive oil secoiridoids, triterpene acids and triterpene alcohols, squalene, αlpha-tocopherol and many others is growing rapidly. -

Environmental Nutrition: Redefining Healthy Food

Environmental Nutrition Redefining Healthy Food in the Health Care Sector ABSTRACT Healthy food cannot be defined by nutritional quality alone. It is the end result of a food system that conserves and renews natural resources, advances social justice and animal welfare, builds community wealth, and fulfills the food and nutrition needs of all eaters now and into the future. This paper presents scientific data supporting this environmental nutrition approach, which expands the definition of healthy food beyond measurable food components such as calories, vitamins, and fats, to include the public health impacts of social, economic, and environmental factors related to the entire food system. Adopting this broader understanding of what is needed to make healthy food shifts our focus from personal responsibility for eating a healthy diet to our collective social responsibility for creating a healthy, sustainable food system. We examine two important nutrition issues, obesity and meat consumption, to illustrate why the production of food is equally as important to consider in conversations about nutrition as the consumption of food. The health care sector has the opportunity to harness its expertise and purchasing power to put an environmental nutrition approach into action and to make food a fundamental part of prevention-based health care. but that it must come from a food system that conserves and I. Using an Environmental renews natural resources, advances social justice and animal welfare, builds community wealth, and fulfills the food and Nutrition Approach to nutrition needs of all eaters now and into the future.i Define Healthy Food This definition of healthy food can be understood as an environmental nutrition approach. -

Healthy Diets Through Agriculture and Food Systems

HEALTHY DIETS THROUGH AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SYSTEMS Understanding the difference between diet, meals, snacks and foods Diet: this refers to everything you consume (food, Snacks: snacks are smaller, less structured meals drink and snacks). Diets in this case do not refer to that are eaten in between regular meal times. special-purpose diets for weight loss or managing particular conditions such as diabetes. Foods: foods can be defined as consumable substances, including drinks, which contain nutrients. Meals: a “meal” has many meanings. Meals may be They can be raw, semi-processed, processed or defined in terms of what food is eaten, how much ultra-processed1. is eaten, when it is eaten how it is prepared, which ingredients are used and how regular it is. Rice and beans in combination provide a healthy and balanced meal ©SIFI 1Ultra-processed products are formulated mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods, containing little or even no whole food content. Many ingredients used to make ultra-processed products are not available from retailers and therefore are not used in the culinary preparation of dishes and meals (FAO, 2015). ©SIFI Variety, balance, Food is essential for our bodies to: proportion and frequency: Eat a wide variety of foods Develop, replace and repair cells and Food is made up of nutrients. Micronutrients such tissues. as vitamins and minerals are needed only in small amounts. Macronutrients such as carbohydrates, The first principle of a balanced diet is that it should Produce energy to keep warm, move and protein and fat are needed in larger amounts. The contain: work. -

Nutrition and Food Safety Tips to Cope with the COVID 19 Pandemic

Nutrition and food safety tips to cope with the COVID 19 pandemic AFRO Nutrition and Food Safety Eat safe and nutritious foods to keep healthy • When you are well nourished the body is better able to resist infection through improved immunity and the integrity of its cells and tissues; • The personal hygiene habits being promoted to prevent COVID19 infection (e.g., washing hands regularly and thoroughly with soap and water or hydro-alcoholic gel) are relevant for avoiding other kinds of infection; • The food hygiene practices summarized in the “Five Keys to Safer Food” remain highly relevant in controlling the pandemic; • In the event of lockdown, shared meals offer very important opportunities to remain socially connected; • If you live alone, pay attention to avoid excess consumption of comfort foods or alcohol. Appropriate nourishment to maintain health and wellbeing • Food is necessary to provide energy for the body’s functions and nutrients to build and repair tissues, prevent sickness and help the body heal from illness; • No one food or supplement can prevent illnesses or supply the body’s needs, so a variety of foods are needed for a balanced diet; • Nutrients that boost immunity and help maintain the integrity of sensitive tissues include vitamin A, C and E, and zinc; • Rich sources include beef liver, yellow fruits and vegetables, green leafy vegetables, nuts and edible seeds, citrus fruits, avocado, sweet peppers, seafood, fish, chicken Drink enough water every day Water is essential for life. It transports nutrients and compounds in blood, regulates your body temperature, gets rid of waste, and lubricates and cushions joints • Drink 8–10 cups of water every day • Avoid soft drinks or sodas and other drinks that are high in sugar (e.g. -

Functional Foods © 2007 Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology

Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology Application of Biotechnology for Functional Foods © 2007 Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology. All rights reserved. No portion of this paper may be reproduced by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher. This report was supported by a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts to the University of Richmond. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Pew Charitable Trusts or the University of Richmond. Contents Preface ..........................................................................................................................................................................5 3 Part 1: Applications of Biotechnology for Functional Foods ..................................................................7 Part 2: Legal and Regulatory Considerations Under Federal Law .....................................................37 Summary ...................................................................................................................................................................63 Selected References ..............................................................................................................................................65 Preface ince the earliest days of agricultural biotechnology development, scientists have envisioned harnessing the power of genetic engineering to enhance nutritional and other properties of foods for consumer benefit. The first -

Diet and Nutrition

The quality of the food you eat can impact your overall physical and mental health. Eating nutritious foods can go a long way toward achieving a healthy lifestyle, so make every bite count. Unhealthy diets lead to major health At the same time, mental illnesses are problems like diabetes, heart disease, the biggest cause of disability and illness obesity, and cancer. Because of this, poor in the world. Depression alone is one of diet is the main cause of early death in the top ve leading causes of disability developed countries. Nearly 20% of all across the planet. deaths worldwide can be linked to unhealthy eating habits. A healthy diet includes a full range of vegetables, fruits, legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans), sh, whole grains (rice, quinoa, oats, breads, etc.), nuts, avocados and olive oil to support a healthy brain. Sweet and fatty foods should be special treats, not the staples of your diet. People who eat a diet high in whole foods Highly processed, fried and sugary foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, whole have little nutritional value and should be grains, legumes, sh and unsaturated fats avoided. Research shows that a diet that (like olive oil) are up to 35% less likely to regularly includes these kinds of foods develop depression than people who eat can increase the risk of developing less of these foods. depression by as much as 60%. Good nutrition starts in the womb. The children of women who eat diets high in processed, fried and sugary foods during pregnancy have more emotional problems in childhood. -

EAT a HEALTHY DIET We Make Dozens of Decisions Every Day

YOUR HEALTHIEST SELF Physical Wellness Checklist Positive physical health habits can help decrease your stress, lower your risk of disease, and increase your energy. Here are tips for improving your physical health: EAT A HEALTHY DIET We make dozens of decisions every day. When it comes to deciding what to eat and feed our families, it can be a lot easier than you might think to make smart choices. A healthy eating plan not only limits unhealthy foods, but also includes a variety of healthy foods. Find out which foods to add to your diet and which to avoid. TO EAT A HEALTHIER DIET: o Replace saturated fats in your diet o Choose more complex carbs. Eat more with unsaturated fats. Use olive, complex carbs, like starches and fiber. canola, or other vegetable oils instead These are found in whole-grain breads, of butter, meat fats, or shortening. cereals, starchy vegetables, and legumes. o Cut back on sodium. Use fresh poultry, o Cut added sugars. Pick food with little fish, and lean meat, rather than canned, or no added sugar. Use the Nutrition smoked, or processed. Choose fresh or Facts label to choose packaged foods frozen vegetables that have no added with less total sugar. salt and foods that have less than 5% of o Switch to whole grains the Daily Value of sodium per serving. Get more fiber. and add different kinds of vegetables, Rinse canned foods. beans, nuts, and seeds to your diet. For other wellness topics, please visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits. -

Download the Diet Comparison Guide

Diet Comparison Guide What you should know about today’s popular diets. Brought to you by MyLifeStages weight management experts Dr. Tom Hopkins, MD, and Erika Deshmukh, MS, RD. Doctor ’s Orders 5 Guidelines for Lasting Results Look for life-long approaches to healthy eating and avoid “dieting,” which is only a 1/ temporary solution. 2/ Avoid diets that are too restrictive, and eliminate important vitamins, minerals and nutrients. 3/ Strive to achieve a nutritionally-balanced diet with healthy foods from each food group. 4/ Achieve a healthy weight with a calorically-balanced diet and routine exercise. Plant-based diets are best for health and longevity. Make fruits, vegatables and whole grains 5/ your diet mainstay. Side-by-side comparisons of 12 popular diets Diet Theory/ Caffeine? Alcohol? Length Cost? Health Health Doctor’s Name Concept/Premise of Diet? Pros Cons Final Say A vegan diet eliminates all animal In Avoid Life-long Average 1) May decrease heart disease 1) Need to be diligent in Studies have shown products including meat, fish, poultry, moderation alcoholic 2) Generally lower in saturated meeting nutritional that a plant-based diet dairy and eggs. drinks that fat requirements, particularly is the best for health are clarified 3) High in fiber if eating lots of iron, B-12, zinc, D and longevity. Requires Foods allowed include grains, beans, using fruits and vegetables vitamins and omega-3s diligence in keeping up legumes, vegetables and fruits. It should animal- with enough fruits, veggies include a higher intake of vegetables that derived to meet nutritional needs, are rich in iron and calcium.