CHSTM 2020 Into the Clouds with Joanne Simpson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapid Intensification of a Sheared Tropical Storm

OCTOBER 2010 M O L I N A R I A N D V O L L A R O 3869 Rapid Intensification of a Sheared Tropical Storm JOHN MOLINARI AND DAVID VOLLARO Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York (Manuscript received 10 February 2010, in final form 28 April 2010) ABSTRACT A weak tropical storm (Gabrielle in 2001) experienced a 22-hPa pressure fall in less than 3 h in the presence of 13 m s21 ambient vertical wind shear. A convective cell developed downshear left of the center and moved cyclonically and inward to the 17-km radius during the period of rapid intensification. This cell had one of the most intense 85-GHz scattering signatures ever observed by the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM). The cell developed at the downwind end of a band in the storm core. Maximum vorticity in the cell exceeded 2.5 3 1022 s21. The cell structure broadly resembled that of a vortical hot tower rather than a supercell. At the time of minimum central pressure, the storm consisted of a strong vortex adjacent to the cell with a radius of maximum winds of about 10 km that exhibited almost no tilt in the vertical. This was surrounded by a broader vortex that tilted approximately left of the ambient shear vector, in a similar direction as the broad precipitation shield. This structure is consistent with the recent results of Riemer et al. The rapid deepening of the storm is attributed to the cell growth within a region of high efficiency of latent heating following the theories of Nolan and Vigh and Schubert. -

Nasa.Gov Determine Their Severity Now Are a Little Less Mysterious

Print Close Related Links January 12, 2004 - (date of web publication) For more information contact: Elvia Thompson A "HOT TOWER" ABOVE THE EYE CAN MAKE HURRICANES Headquarters, Washington STRONGER (Phone: 202/358-1696) They are called hurricanes in the Rob Gutro Atlantic, typhoons in Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, the West Pacific, Md. and tropical (Phone: 301/286-4044) cyclones worldwide; but wherever these For information about the TRMM Satellite storms roam, the on the Internet, visit: forces that http://trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov determine their http://www.eorc.nasda.go.jp/TRMM severity now are a little less mysterious. NASA scientists, For information about NOAA's National Hurricane Center click here. using data from the Tropical Rainfall For information about Hurricane Measuring Mission Item 1 (TRMM) satellite, Bonnie, click here. have found "hot High resolution image tower" clouds are associated with tropical cyclone intensification. Viewable Images Owen Kelley and John Stout of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., and George Mason University will present their findings at the American Meteorological Society annual meeting in Seattle on Monday, January 12. Caption for Item 1: AN UNUSUALLY DEEP CONVECTIVE TOWER IN Kelley and Stout define a "hot tower" as a rain cloud that reaches at HURRICANE BONNIE AS BONNIE least to the top of the troposphere, the lowest layer of the atmosphere. INTENSIFIED It extends approximately nine miles (14.5 km) high in the tropics. These towers are called "hot" because they rise to such altitude due to This TRMM Precipitation Radar overflight of Hurricane Bonnie shows an 11 mile the large amount of latent heat. -

Thesis Latent Heating and Mixing Due to Entrainment In

THESIS LATENT HEATING AND MIXING DUE TO ENTRAINMENT IN TROPICAL DEEP CONVECTION Submitted by Clayton J. McGee Department of Atmospheric Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2013 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Susan van den Heever Eric Maloney Richard Eykholt ABSTRACT LATENT HEATING AND MIXING DUE TO ENTRAINMENT IN TROPICAL DEEP CONVECTION Recent studies have noted the role of latent heating above the freezing level in reconciling Riehl and Malkus' Hot Tower Hypothesis (HTH) with evidence of diluted tropical deep convective cores. This study evaluates recent modifications to the HTH through Lagrangian trajectory analysis of deep convective cores in an idealized, high-resolution cloud-resolving model (CRM) simulation. A line of tropical convective cells develops within a high-resolution nested grid whose boundary conditions are obtained from a large-domain CRM simulation approaching radiative-convective equilibrium (RCE). Microphysical impacts on latent heating and equivalent potential temperature (!e) are analyzed along trajectories ascending within convective regions of the high-resolution nested grid. Changes in !e along backward trajectories are partitioned into contributions from latent heating due to ice processes and a residual term. This residual term is composed of radiation and mixing. Due to the small magnitude of radiative heating rates in the convective inflow regions and updrafts examined here, the residual term is treated as an approximate representation of mixing within these regions. The simulations demonstrate that mixing with dry air decreases !e along ascending trajectories below the freezing level, while latent heating due to freezing and vapor deposition increase !e above the freezing level. -

1999 Atmospheric Research Technical Highlights (PDF, 4.8

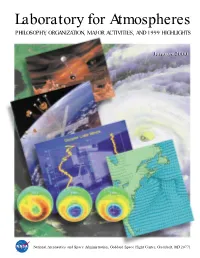

Laboratory for Atmospheres PHILOSOPHY, ORGANIZATION, MAJOR ACTIVITIES, AND 1999 HIGHLIGHTS JanuaryJanuary 20002000 National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 NASA GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Laboratory for Atmospheres PHILOSOPHY, ORGANIZATION, MAJOR ACTIVITIES, AND 1999 HIGHLIGHTS January 2000 2 1 3 4 5 6 1 Hurricane Fran as rendered on NASA 5 An example of the very realistic patterns computers using data captured by NOAA’s of cyclones and fronts that appear in surface GOES-8 satellite on September 4, 1996. wind fields generated by the 1-degree latitude by 1-degree longitude ver- 2 The Cassini Mission to Saturn and its sion of the GEOS global atmospheric model. moon, Titan. 6 October average total column ozone as 3 The Leonardo-BRDF formation of measured by the Total Ozone Mapping microsatellites viewing the Himalayas and Spectrometer (TOMS). Red and yellow indi- the Indian subcontinent. cate high overhead column amounts. Blue 4 The Goddard Lidar Observatory for Winds and purple show low values. The Antarctic (GLOW), a mobile Doppler lidar system Ozone hole appears as the very low column designed for field measurement of wind pro- amounts in the two later years. files from the surface into the stratosphere. A profile of wind speed and direction appears in the foreground, along with wind data obtained from a balloon sonde. Cover designed by Bill Welsh National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, MD 20771 January 2000 Dear Reader: Welcome to the Laboratory for Atmospheres and to our review of the Laboratory’s accomplishments for 1999! The Laboratory for Atmospheres consists of four hundred scientists, technologists, and administrative per- sonnel working within the Earth Sciences Directorate of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). -

Latent Heating and Mixing Due to Entrainment in Tropical Deep Convection

816 JOURNAL OF THE ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES VOLUME 71 Latent Heating and Mixing due to Entrainment in Tropical Deep Convection CLAYTON J. MCGEE AND SUSAN C. VAN DEN HEEVER Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado (Manuscript received 13 May 2013, in final form 31 July 2013) ABSTRACT Recent studies have noted the role of latent heating above the freezing level in reconciling Riehl and Malkus’ hot tower hypothesis (HTH) with evidence of diluted tropical deep convective cores. This study evaluates recent modifications to the HTH through Lagrangian trajectory analysis of deep convective cores in an idealized, high-resolution cloud-resolving model (CRM) simulation that uses a sophisticated two-moment microphysical scheme. A line of tropical convective cells develops within a finer nested grid whose boundary conditions are obtained from a large-domain CRM simulation approaching radiative convective equilibrium (RCE). Microphysical impacts on latent heating and equivalent potential temperature (ue) are analyzed along trajectories ascending within convective regions of the high-resolution nested grid. Changes in ue along backward trajectories are partitioned into contributions from latent heating due to ice processes and a re- sidual term that is shown to be an approximate representation of mixing. The simulations demonstrate that mixing with dry environmental air decreases ue along ascending trajectories below the freezing level, while latent heating due to freezing and vapor deposition increase ue above the freezing level. Latent heating contributions along trajectories from cloud nucleation, condensation, evaporation, freezing, deposition, and sublimation are also quantified. Finally, the source regions of trajectories reaching the upper troposphere are identified. -

Convective Towers in Eyewalls of Tropical Cyclones Observed by the Trmm Precipitation Radar in 1998–2001

P1.43 CONVECTIVE TOWERS IN EYEWALLS OF TROPICAL CYCLONES OBSERVED BY THE TRMM PRECIPITATION RADAR IN 1998–2001 Owen A. Kelley* and John Stout TRMM Science Data and Information System, NASA Goddard, Greenbelt, Maryland Center for Earth Observation and Space Research, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia Abstract—The Precipitation Radar of the Tropical cyclone. In the mid-1960s, the mesoscale structure Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) is the first surrounding convective towers became a topic of space-borne radar that is capable of resolving the research (Malkus and Riehl 1964). Since the 1980s, detailed vertical structure of convective towers. one mesoscale structure in particular has been studied: During 1998 to 2001, the Precipitation Radar convective bursts, which include multiple convective overflew approximately one hundred tropical towers (Steranka et al. 1986; Rodgers et al. 2000; cyclones and observed their eyewalls. Many Heymsfield et al. 2001). Most papers about convective eyewalls had one or more convective towers in towers and convective bursts are descriptive. In them, especially the eyewalls of intensifying contrast, only a few papers attempted to be predictive, cyclones. A convective tower in an eyewall is such as showing how a convective tower or burst most likely to be associated with cyclone intensi- contributes to tropical cyclone formation (Simpson et al. fication if the tower has a precipitation rate of 2 1998) or intensification (Steranka et al. 1986). mm/h at or above an altitude of 14 km. Alterna- Before the 1997 launch of the Tropical Rainfall tively, the tower can have a 20 dBZ radar reflec- Measuring Mission (TRMM), no dataset existed that tivity at or above 14.5 km. -

Fireline Leadership in the Brave New World of Weather Modification & Modern Wildland Fire Behavior

FIRELINE LEADERSHIP IN THE BRAVE NEW WORLD OF WEATHER MODIFICATION & MODERN WILDLAND FIRE BEHAVIOR Keep Informed on Fire Weather Conditions and Obtain Forecasts Base All Actions on Current and Expected Fire Behavior Unfamiliar with Weather and Local Factors Influencing Fire Behavior LEARNING NEW INDICATORS Fred J. Schoeffler Sheff, LLC January 2008 INTRODUCTION It’s almost ten years ago to the day that I wrote a similar paper and made a similar presentation to my esteemed Hot Shot colleagues. My goal is to hopefully educate you all about a very real, very disturbing phenomenon occurring worldwide on a daily basis. In fact NOAA readily admits to over fifty (50) on-going Weather Modification projects occurring in the United States today. This doesn’t include what “The Government,” the military, and…(others)…are doing. Weather Modification affects us all. I bet it’s safe to say you often look at clouds and think they look artificial or you just know they are not real. The very first Fire Order is “Keep Informed on Fire Weather Conditions and Forecasts.” So by extension, Weather Modification affects us as Fireline Supervisors, because weather influences fire behavior. The most unpredictable element of weather is, of course, the wind. Many of the Weather Modification projects radically affect the wind, especially HAARP, so much of the following information is about other weather and the new indicators you’ll need to watch for. And please note that not all the information presented in this paper deals with “weather modification,” per se. My goal is to show you, among other things, what indicators to look for – in the clouds and in the smoke columns. -

A Vortical Hot Tower Route to Tropical Cyclogenesis

JANUARY 2006 M ONTGOMERY ET AL. 355 A Vortical Hot Tower Route to Tropical Cyclogenesis M. T. MONTGOMERY,M.E.NICHOLLS,T.A.CRAM, AND A. B. SAUNDERS Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado (Manuscript received 5 December 2003, in final form 22 February 2005) ABSTRACT A nonhydrostatic cloud model is used to examine the thermomechanics of tropical cyclogenesis under realistic meteorological conditions. Observations motivate the focus on the problem of how a midtropo- spheric cyclonic vortex, a frequent by-product of mesoscale convective systems during summertime condi- tions over tropical oceans, may be transformed into a surface-concentrated (warm core) tropical depression. As a first step, the vortex transformation is studied in the absence of vertical wind shear or zonal flow. Within the cyclonic vorticity-rich environment of the mesoscale convective vortex (MCV) embryo, the simulations demonstrate that small-scale cumulonimbus towers possessing intense cyclonic vorticity in their cores [vortical hot towers (VHTs)] emerge as the preferred coherent structures. The VHTs acquire their vertical vorticity through a combination of tilting of MCV horizontal vorticity and stretching of MCV and VHT-generated vertical vorticity. Horizontally localized and exhibiting convective lifetimes on the order of 1 h, VHTs overcome the generally adverse effects of downdrafts by consuming convective available po- tential energy in their local environment, humidifying the middle and upper troposphere, and undergoing diabatic vortex merger with neighboring towers. During metamorphosis, the VHTs vortically prime the mesoscale environment and collectively mimic a quasi-steady diabatic heating rate within the MCV embryo. A quasi-balanced toroidal (transverse) circu- lation develops on the system scale that converges cyclonic vorticity of the initial MCV and small-scale vorticity anomalies generated by subsequent tower activity. -

Hurricane Sandy (2012), the TRMM Satellite, and the Physics of the Hot Towers

Hurricane Sandy (2012), the TRMM Satellite, and the Physics of the Hot Towers Alan Stahler of KVMR interviews Owen Kelley of NASA Goddard — Broadcast on Tuesday, 27 November 2012, on the 15th Anniversary of the Launch of the TRMM Satellite Broadcast: 38.5 minutes duration starting at noon PST on KVMR-FM, Nevada City, California Contacts: [email protected], 530-265-9073, and [email protected], 301-614-5245 00:00 The TRMM Instruments Stahler: Owen, how does TRMM, the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, see rain? Kelley: It is called the flying rain gauge1 because it has every instrument ever used from space to measure rain. It has an infrared camera that sees how high and cold the clouds are... Stahler: You can see those images from GOES. GOES is a geostationary satellite. That means it hovers over the equator and gives us our daily weather picture. Kelley: Since the 60s, we've had that view from space.2 Stahler: Because it's infrared, it is essentially giving you the temperature of the clouds, and the colder the cloud, the higher up it is in the atmosphere. This lets you see how high, how tall the clouds are... Kelley: And that matters because air doesn't get lifted from the earth's surface to high up unless there is energy being transformed into strong updrafts. So [cloud top temperature] tells you something about the physics that is going on inside the clouds. If you are out on a sunny day and a little puffy cloud comes along, you don't get worried, but if you suddenly see it get dark and a cloud shoots up and starts to cover a lot of territory, then you know it's a big storm cloud and you might not want to set out on a hike. -

NASA Sees a 'Hot Tower' in Newborn Eastern Pacific Tropical Depression 2E 21 May 2012

NASA sees a 'hot tower' in newborn eastern Pacific Tropical Depression 2E 21 May 2012 that a tropical cyclone with a hot tower in its eyewall was twice as likely to intensify within the next six hours, than a cyclone that lacked a tower. The "eyewall" is the ring of clouds around a cyclone's central eye. When NASA's TRMM satellite passed over TD02E on May 21, 2012 at 08:50 UTC (4:50 a.m. EDT), data revealed a hot tower over 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) high. That's an indication that the storm is going to intensify, and that's one factor that forecasters at the National Hurricane Center are using in their forecast, which calls for TD02E to become a tropical storm later in the day on May 21. TRMM also measured rainfall within the tropical depression, and found that isolated areas of heavy When NASA's TRMM satellite passed over TD02E on rain (falling at a rate of 2 inches/50 mm per hour) May 21, 2012, at 08:50 UTC (4:50 a.m. EDT), data were seen in the northwestern quadrant of the revealed a hot tower over 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) high. storm. Light-to-moderate rainfall was falling TRMM also measured rainfall within the tropical throughout the rest of the storm. depression, and found that isolated areas of heavy rain (falling at a rate of 2 inches/50 mm per hour (appearing in red)) were seen in the northwestern quadrant of the At 5 a.m. EDT on May 21, TD02E had maximum storm. -

ASLI News ASLI News ASLI NEWS

ASLI News ASLI News ASLI NEWS June 2010 Welcome to the second issue in 2010 of ASLI News! In this issue, there are some updates about the upcoming 2011 ASLI Conference, a nice summary of the 2010 ASLI Field Trip in Atlanta, some ASLI Business news, and a couple of articles that may be of interest to our community. Also there is a list of new and upcoming atmospheric science titles. Enjoy! Join the 14th Conference of the Atmospheric Science Librarians International (ASLI) in Seattle, Washington! CALL for PAPERS 14th Conference of Atmospheric Science Librarians International (ASLI): Communicating Weather and Climate: Making the Most of the Information, 26–27 January 2011, Seattle, Washington. Communication is a key component of the information world, and it can be seen in a variety of ways: from finding that elusive fact or article reference, to showcasing research or data collections available through both print and digital media, or taking a dataset, analyzing it and utilizing it to create a new resource. With the help of the internet and new technology, communication is now paramount, but is constantly evolving, altering how we search for, manage, and use the treasure troves of meteorological and climate data and information. Check the ASLI listserv for the full call for papers announcement. Please submit proposals electronically to: Kari A. Kozak; ASLI Chair-elect; University of Iowa Libraries, 453 Van Allen Hall; Iowa City, IA, 52242; ph: 319-335-3024; [email protected]. The deadline for receiving abstracts is October 1, 2010. Chihuly and Coffee - Highlights from the ASLI Annual Meeting Field Trip, January 2010 Judi Triplehorn once again planned an interesting and fun field trip for our annual meeting attendees. -

SI System of Measurement

6.3 Joanne Simpson Dr. Joanne Simpson was the first woman to serve as president of the American Meteorological Society. Her road to success was not easy. She chose to forge ahead in the field of meteorology for the sake of women who would enter the field after her. Early goals Determined even more, Simpson pursued her dream. She took a course with Herbert Riehl, a Joanne Simpson was born leader in the field of tropical meteorology. She in 1923 in Boston, asked Riehl if he would be her advisor and he Massachusetts. At a young agreed. Not surprisingly, Simpson chose to study age, Simpson was clouds. Her new advisor thought it would be a determined to have a perfect topic “for a little girl to study.” Throughout career that would provide her Ph.D. program, she studied in an unsupportive her with financial academic environment. She persevered and independence. Her mother, became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in a journalist, remained in a meteorology. difficult marriage because she could not afford to Working woman provide for her children on As a woman, Simpson did have difficulty finding a her own. Simpson knew at age ten that she wanted job. Eventually she became an assistant physics to be able to support herself and any future professor. Two years later, she took a job at Woods children. Hole Oceanographic Institute to study tropical So Simpson’s journey began. As a child, Simpson clouds. People at the time believed clouds were loved clouds. She spent time gazing at clouds produced by the weather and were not the cause when she sailed off the Cape Cod coast.