Shared-Use Bus Priority Lanes on City Streets: Case Studies in Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic

MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration for Streets and Highways Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic Dotted line indicates edge of binder spine. MM UU TT CC DD U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration 2003 Edition Page i The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is approved by the Federal Highway Administrator as the National Standard in accordance with Title 23 U.S. Code, Sections 109(d), 114(a), 217, 315, and 402(a), 23 CFR 655, and 49 CFR 1.48(b)(8), 1.48(b)(33), and 1.48(c)(2). Addresses for Publications Referenced in the MUTCD American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) 444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 249 Washington, DC 20001 www.transportation.org American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) 8201 Corporate Drive, Suite 1125 Landover, MD 20785-2230 www.arema.org Federal Highway Administration Report Center Facsimile number: 301.577.1421 [email protected] Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) 120 Wall Street, Floor 17 New York, NY 10005 www.iesna.org Institute of Makers of Explosives 1120 19th Street, NW, Suite 310 Washington, DC 20036-3605 www.ime.org Institute of Transportation Engineers -

Madison Avenue Dual Exclusive Bus Lane Demonstration, New York City

HE tV 18.5 U M T A-M A-06-0049-84-4 a A37 DOT-TSC-U MTA-84-18 no. DOT- Department SC- U.S T of Transportation UM! A— 84-18 Urban Mass Transportation Administration Madison Avenue Dual Exclusive Bus Lane Demonstration - New York City j ™nsportat;on JUW 4 198/ Final Report May 1984 UMTA Technical Assistance Program Office of Management Research and Transit Service UMTA/TSC Project Evaluation Series NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. - POT- Technical Report Documentation Page TS . 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient s Catalog No. 'A'* tJMTA-MA-06-0049-84-4 'Z'i-I £ 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date MADISON AVENUE DUAL EXCLUSIVE BUS LANE DEMONSTRATION. May 1984 NEW YORK CITY 6. Performing Organization Code DTS-64 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Authors) J. Richard^ Kuzmyak : DOT-TSC-UMTA-84-18 9^ Performing Organization Name ond Address DEPARTMENT OF 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) COMSIS Corporation* transportation UM427/R4620 11501 Georgia Avenue, Suite 312 11. Controct or Grant No. DOT-TSC-1753 Wheaton, MD 20902 JUN 4 1987 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Urban Mass Transportation Admi ni strati pg LIBRARY August 1980 - May 1982 Office of Technical Assistance 14. -

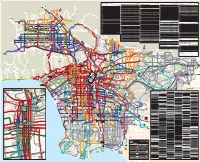

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

Module 6. Hov Treatments

Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Module 6. TABLE OF CONTENTS MODULE 6. HOV TREATMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 6.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................ 6-5 TREATMENTS ..................................................... 6-6 MODULE OBJECTIVES ............................................. 6-6 MODULE SCOPE ................................................... 6-7 6.2 DESIGN PROCESS .......................................... 6-7 IDENTIFY PROBLEMS/NEEDS ....................................... 6-7 IDENTIFICATION OF PARTNERS .................................... 6-8 CONSENSUS BUILDING ........................................... 6-10 ESTABLISH GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ............................... 6-10 ESTABLISH PERFORMANCE CRITERIA / MOES ....................... 6-10 DEFINE FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ............................. 6-11 IDENTIFY AND SCREEN TECHNOLOGY ............................. 6-11 System Planning ................................................. 6-13 IMPLEMENTATION ............................................... 6-15 EVALUATION .................................................... 6-16 6.3 TECHNIQUES AND TECHNOLOGIES .................. 6-18 HOV FACILITIES ................................................. 6-18 Operational Considerations ......................................... 6-18 HOV Roadway Operations ...................................... 6-20 Operating Efficiency .......................................... 6-20 Considerations for 2+ Versus 3+ Occupancy Requirement ............. 6-20 Hours of Operations .......................................... -

Bowie Washington Clinton Oxon Hill Camp Springs

503 Z7 to/from Laurel to/from Columbia 409 Z2 to/from Olney C8 to/from White Flint to/from Elkridge Z11 to/from Laurel Racetrack Burtonsville Park & Ride Montgomery 295 St 302 Main St Z6 Sandy Spring Rd 89M WESTFARM to/from Burtonsville/ RTA provides local service Castle Blvd Z7 Old Sandy 87 Z2 Z7 to/from throughout Central Maryland, Spring Rd Z8 Z6 Paul S. Sarbanes Transit Center to/from Greencastle/Briggs Chaney (Silver Spring m ) Sweitzer Ln including Laurel. 503 COLUMBIA PIKE 302 Gorman Ave 5th St WHITE OAK 409 K6 Industrial Intercounty Connector Van Dusen Rd 87 Pkwy CALVERTON 141 89 89M 89 Laurel Tech Broadbirch Dr 141 to/from Rd Galway Dr Gaithersburg Park & Ride Calverton Blvd Laurel 301 Washington Blvd Van Dusen Rd Fort Meade Rd B30 Z6 Z7 Regional Z7 302 LAUREL Baltimore-Washingtonto/from Pkwy BWI Airport via Arundel Mills Z7 502 Hospital Ashford 4th St LOCKWOOD DR Blvd 502 to/from Arundel Mills Z11 K9 R2 Beltsville Dr 87 C8 FDA Cherry Ln Z2 C8 Red Clay Rd PATUXENT RIVER Plum Orchard Dr Towne Centre 502 Old Z8 Mulberry St Laurel 87 Annapolis Rd Broadbirch Dr Broadbirch R2 Z6 95 301 White Oak Cherry Hill Rd 89 Cherry Ln Adventist St Cypress 302 502 89M Laurel-Bowie Federal Medical Center 87 Z7 Rd Research South Laurel NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE AmmendaleVirginia Rd B30 Muirkirk Park & Ride Center 86 Manor Ritz Way Baltimore Ave COLUMBIA PIKE Rd Rd Z7 Centerpark Powder Mill Rd Laurel-Bowie Rd89M 87 Office Park Contee Rd 301 89 Z2, Z6, Z7, Z8, Z11 to/from Powder Mill Rd Muirkirk Rd 89M Muirkirk Paul S. -

Purple Line Functional Plan? 6 Table 9 Stewart Avenue to CSX/WMATA Right-Of-Way 23

Approved and Adopted September 2010 purple line F u n c t i o n a l P l a n Montgomery County Planning Department The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission P u r p l e L i n e F u n c t i o n a l P l a n I A p p r o v e d a n d A d o p t e d 1 p u r p l e l i n e f u n c t i o n a l p l a n Approved and Adopted a b s t r a c t The Commission is charged with preparing, adopting, and amending or extending The General Plan (On Wedges and Corridors) for the Physical This plan for the Purple Line transit facility through Montgomery County Development of the Maryland-Washington Regional District in Montgomery contains route, mode, and station recommendations. It is a comprehensive and Prince George’s Counties. amendment to the approved and adopted 1990 Georgetown Branch Master Plan Amendment. It also amends The General Plan (On Wedges and The Commission operates in each county through Planning Boards Corridors) for the Physical Development of the Maryland-Washington appointed by the county government. The Boards are responsible for all Regional District in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties, as local plans, zoning amendments, subdivision regulations, and amended, the Master Plan of Highways for Montgomery County, the administration of parks. Countywide Bikeways Functional Master Plan, the Bethesda-Chevy Chase Master Plan, the Bethesda Central Business District Sector Plan, the Silver The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission encourages Spring Central Business District and Vicinity Sector Plan, the North and West the involvement and participation of individuals with disabilities, and its Silver Spring Master Plan, the East Silver Spring Master Plan, and the facilities are accessible. -

Local Government and the Challenges of Service Delivery: the Nigeria Experience

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 15, No.7, 2013) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND THE CHALLENGES OF SERVICE DELIVERY: THE NIGERIA EXPERIENCE Oluwatobi ADEYEMI Department of Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile- Ife, Nigeria ABSTRACT Nigeria is a Federation of thirty-six States and a Federal Capital Territory located in Abuja. It consists of 774 Local Government Councils. The Constitution recognizes Local Government as the third tier of government whose major responsibility is to ensure affective service delivery to the people, and also enhance sustainable development at the grassroot. The incapacity to generate its own revenue sources leads to its continued dependence on federal allocation, the result of which makes it a stooge rather than a partner in developmental process among the tiers of government in Nigeria leading to little evidence of performance at local level. This study examines the constitutional/functional roles of local government councils in Nigeria in relation to service delivery. It provides a prospect of identifying the factors that has hampered the effectiveness of this institution at grassroots governance in Nigeria. The paper, however provide recommendations in form of solutions to these challenges at the local level. Keywords: Local Government, Services Delivery, Centralization, Decentralization, Fiscal Federalism, Citizen Centered Local Governance, Sustainable Development: 84 INTRODUCTION Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with a population of 140 million (Amakom, 2009), 64 percent of whom live in rural areas. In the pursuit of development at the grassroot, local government was created to provide level of measurable services to rural dwellers. -

Local Government Association of the Northern Territory

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY HOUSE OF REPRESENIATIVE8~STANDJ~cQMMII1TEEON~~ ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER AFFAIRS SUBMISSION TO THE PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO CAPACITY BUILDING IN INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS AUGUST 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. What is this submission about? I 2. What does the Local Government Association stand for and who are its members? 2-3 3. How can capacity be improved? 3-4 4. How can organizations better deliver services? 5-7 5. How can government agencies improve management structures and policy directions? 8-9 2 1. What is this submission about? This submission is about capacity building in Aboriginal Communities in the Northern Territory. It is in response to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs inquiry into capacity building in Indigenous communities. This submission emphasises the role that local government and local governing bodies play in relation to the issue of building capacity in Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory. The reason for this, is that in many instances Councils constitute the only, or most focal, administrative organisation in Indigenous communities and therefore, the view taken here is that questions about capacity building in such communities are very much linked to the role and function of Councils. The Association is very much committed to capacity building for Councils in the Northern Territory indeed, it constitutes an objective of the Association (see next section). The Association is very much a service organisation to local government in the Northern Territory and it would like to expand its range of services so that it can be in a position to offer them at a level similar to that afforded to Councils by their respective associations interstate. -

Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (Part B)

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 2 BUS TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. BUS CAPACITY BASICS ....................................................................................... 2-1 Overview..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 2-1 Types of Bus Facilities and Service ............................................................................ 2-3 Factors Influencing Bus Capacity ............................................................................... 2-5 Vehicle Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-5 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-13 Fundamental Capacity Calculations .......................................................................... 2-15 Vehicle Capacity................................................................................................... 2-15 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-22 Planning Applications ............................................................................................... 2-23 2. OPERATING ISSUES............................................................................................ 2-25 Introduction.............................................................................................................. -

Role of High-Occupancy-Vehicle Lanes Highway Construction Management In

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1280 131 Role of High-Occupancy-Vehicle Lanes In• Highway Construction Management ALLAN E. PINT, CHARLEEN A. ZIMMER, AND FRANCIS E. LOETTERLE The Minnesota Department of Transportation (Mn/DOT) is con 3. How has construction affected use of the HOV lane? structing 1-394 along the portion of US-12 that extends from 4. What was the role of the HOV lane in traffic management do\\lntown MinneapolL5 to the suburb of Wayzata. When com during construction? pleted, I-394 will have high-occupancy-vehicle (HOV) lanes. 5. How has the HOV lane affected the highway construction Mn/DOT builr a temporary HOV lane along US-12 before con structing 1-394 to introduce th , HOV lane concept to commuters project? and to improve capacity during construction. Mn/DOT and the FHW A have been conducting an evaluation of this temporary HOV lane. Phase I evaluated operation in an arterial highway FUTURE 1-394 TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM environment before construction. Phase II evaluated operation and use of the HOV lane during highway construction. Five key When completed, 1-394 will have two mixed traffic lanes in issues were addressed in the Phase II evaluation: (a) what can each direction and two lanes for high-occupancy vehicles (3 be learned about the design and operation of HOV lanes, (b) mi of separated reversible lanes and 8 mi of concurrent flow who uses HOV lanes and what factors cause people to choose diamond lanes). I-394 is being built along the alignment of carpooling or the bus over driving alone, (c) how has con truction existing US-12, from downtown Minneapolis to the third-ring affected use of the HOV lane, (d) what was the role of the HOV lane in construction traffic management, and (e) how has the suburban municipality of Wayzata, 11 mi to the west. -

Local Motion Transit Ambassador Information and Application Packet August – October 2008

Local Motion Transit Ambassador Information and Application Packet August – October 2008 Thank you for your interest in the Local Motion Transit Ambassador program! The objective of the program is to encourage residents and commuters to make more trips by transit and less by personal vehicle. Ambassadors work with Local Motion program manager to complete various tasks and earn points towards incentive prizes; ambassadors choose their level of involvement based on interest and availability. Here’s how it works: - Transit Ambassador program will run August 1 – October 31 - Complete and submit the Transit Ambassador application and knowledge questionnaire - Participate in a variety of outreach and communications tasks based on interest and availability - Each month, ambassadors submit a report, and supporting documentation where necessary, to Local Motion program manager - Approved ambassadors will receive a Local Motion Transit Ambassador t-shirt to be worn at outreach and special events - At the close of each phase, a celebratory recognition luncheon and program recap will take place to award prizes and discuss ambassador experiences GREAT PRIZES! 100 points 75 points – $100 gift card 50 points – $50 gift card - Nintendo Wii - Giant - Trader Joe’s - Borders - Personal chef service - Walmart - Best Buy - Barnes & Noble - iPhone 3G, 16GB - Whole Foods - REI - SmarTrip - Home cleaning service provided - Shoppers - Target - AMC Theaters by The Maid Home Services Task list and point allocations* 30 points each - Attend and speak at event to -

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens In the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area JANUARY 2017 Transfer Station Station Features Red Line • Glenmont / Shady Grove Bus to Airport System Orange Line • New Carrollton / Vienna Parking Station Legend Blue Line • Franconia-Springfield / Largo Town Center in Service Map Hospital Under Construction Green Line • Branch Ave / Greenbelt Airport Full-Time Service wmata.com Yellow Line • Huntington / Fort Totten Customer Information Service: 202-637-7000 Connecting Rail Systems Rush-Only Service: Monday-Friday Silver Line • Wiehle-Reston East / Largo Town Center TTY Phone: 202-962-2033 6:30am - 9:00am 3:30pm - 6:00pm Metro Transit Police: 202-962-2121 Glenmont Wheaton Montgomery Co Prince George’s Co Shady Grove Forest Glen Rockville Silver Spring Twinbrook B30 to Greenbelt BWI White Flint Montgomery Co District of Columbia College Park-U of Md Grosvenor - Strathmore Georgia Ave-Petworth Takoma Prince George’s Plaza Medical Center West Hyattsville Bethesda Fort Totten Friendship Heights Tenleytown-AU Prince George’s Co Van Ness-UDC District of Columbia Cleveland Park Columbia Heights Woodley Park Zoo/Adams Morgan U St Brookland-CUA African-Amer Civil Dupont Circle War Mem’l/Cardozo Farragut North Shaw-Howard U Rhode Island Ave Brentwood Wiehle-Reston East Spring Hill McPherson Mt Vernon Sq NoMa-Gallaudet U New Carrollton Sq 7th St-Convention Center Greensboro Fairfax Co Landover Arlington Co Tysons Corner Gallery Place Union Station Chinatown Cheverly 5A to