Egg Production by the Bay Anchovy Anchoa Mitchilli in Relation to Adult and Larval Prey Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrea RAZ-GUZMÁN1*, Leticia HUIDOBRO2, and Virginia PADILLA3

ACTA ICHTHYOLOGICA ET PISCATORIA (2018) 48 (4): 341–362 DOI: 10.3750/AIEP/02451 AN UPDATED CHECKLIST AND CHARACTERISATION OF THE ICHTHYOFAUNA (ELASMOBRANCHII AND ACTINOPTERYGII) OF THE LAGUNA DE TAMIAHUA, VERACRUZ, MEXICO Andrea RAZ-GUZMÁN1*, Leticia HUIDOBRO2, and Virginia PADILLA3 1 Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México 2 Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura, SAGARPA, Ciudad de México 3 Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México Raz-Guzmán A., Huidobro L., Padilla V. 2018. An updated checklist and characterisation of the ichthyofauna (Elasmobranchii and Actinopterygii) of the Laguna de Tamiahua, Veracruz, Mexico. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 48 (4): 341–362. Background. Laguna de Tamiahua is ecologically and economically important as a nursery area that favours the recruitment of species that sustain traditional fisheries. It has been studied previously, though not throughout its whole area, and considering the variety of habitats that sustain these fisheries, as well as an increase in population growth that impacts the system. The objectives of this study were to present an updated list of fish species, data on special status, new records, commercial importance, dominance, density, ecotic position, and the spatial and temporal distribution of species in the lagoon, together with a comparison of Tamiahua with 14 other Gulf of Mexico lagoons. Materials and methods. Fish were collected in August and December 1996 with a Renfro beam net and an otter trawl from different habitats throughout the lagoon. The species were identified, classified in relation to special status, new records, commercial importance, density, dominance, ecotic position, and spatial distribution patterns. -

Species Anchoa Analis (Miller, 1945)

FAMILY Engraulidae Gill, 1861 - anchovies [=Engraulinae, Stolephoriformes, Coilianini, Anchoviinae, Setipinninae, Cetengraulidi] GENUS Amazonsprattus Roberts, 1984 - pygmy anchovies Species Amazonsprattus scintilla Roberts, 1984 - Rio Negro pygmy anchovy GENUS Anchoa Jordan & Evermann, 1927 - anchovies [=Anchovietta] Species Anchoa analis (Miller, 1945) - longfin Pacific anchovy Species Anchoa argentivittata (Regan, 1904) - silverstripe anchovy, Regan's anchovy [=arenicola] Species Anchoa belizensis (Thomerson & Greenfield, 1975) - Belize anchovy Species Anchoa cayorum (Fowler, 1906) - Key anchovy Species Anchoa chamensis Hildebrand, 1943 - Chame Point anchovy Species Anchoa choerostoma (Goode, 1874) - Bermuda anchovy Species Anchoa colonensis Hildebrand, 1943 - narrow-striped anchovy Species Anchoa compressa (Girard, 1858) - deepbody anchovy Species Anchoa cubana (Poey, 1868) - Cuban anchovy [=astilbe] Species Anchoa curta (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - short anchovy Species Anchoa delicatissima (Girard, 1854) - slough anchovy Species Anchoa eigenmannia (Meek & Hildebrand, 1923) - Eigenmann's anchovy Species Anchoa exigua (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - slender anchovy [=tropica] Species Anchoa filifera (Fowler, 1915) - longfinger anchovy [=howelli, longipinna] Species Anchoa helleri (Hubbs, 1921) - Heller's anchovy Species Anchoa hepsetus (Linnaeus, 1758) - broad-striped anchovy [=brownii, epsetus, ginsburgi, perthecatus] Species Anchoa ischana (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - slender anchovy Species Anchoa januaria (Steindachner, 1879) - Rio anchovy -

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species ID Guide

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Identification Guide Forage Species Identification Guide Basic Morphology Dorsal fin Lateral line Caudal fin This guide provides descriptions and These species are subject to the codes for the forage species that vessels combined 1,700-pound trip limit: Opercle and dealers are required to report under Operculum • Anchovies the Mid-Atlantic Council’s Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment. Find out • Argentines/Smelt Herring more about the amendment at: • Greeneyes Pectoral fin www.mafmc.org/forage. • Halfbeaks Pelvic fin Anal fin Caudal peduncle All federally permitted vessels fishing • Lanternfishes in the Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Dorsal Right (lateral) side Management Unit and dealers are • Round Herring required to report catch and landings of • Scaled Sardine the forage species listed to the right. All species listed in this guide are subject • Atlantic Thread Herring Anterior Posterior to the 1,700-pound trip limit unless • Spanish Sardine stated otherwise. • Pearlsides/Deepsea Hatchetfish • Sand Lances Left (lateral) side Ventral • Silversides • Cusk-eels Using the Guide • Atlantic Saury • Use the images and descriptions to identify species. • Unclassified Mollusks (Unmanaged Squids, Pteropods) • Report catch and sale of these species using the VTR code (red bubble) for • Other Crustaceans/Shellfish logbooks, or the common name (dark (Copepods, Krill, Amphipods) blue bubble) for dealer reports. 2 These species are subject to the combined 1,700-pound trip limit: • Anchovies • Argentines/Smelt Herring • -

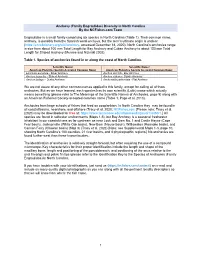

NC-Anchovy-And-Identification-Key

Anchovy (Family Engraulidae) Diversity in North Carolina By the NCFishes.com Team Engraulidae is a small family comprising six species in North Carolina (Table 1). Their common name, anchovy, is possibly from the Spanish word anchova, but the term’s ultimate origin is unclear (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/anchovy, accessed December 18, 2020). North Carolina’s anchovies range in size from about 100 mm Total Length for Bay Anchovy and Cuban Anchovy to about 150 mm Total Length for Striped Anchovy (Munroe and Nizinski 2002). Table 1. Species of anchovies found in or along the coast of North Carolina. Scientific Name/ Scientific Name/ American Fisheries Society Accepted Common Name American Fisheries Society Accepted Common Name Engraulis eurystole - Silver Anchovy Anchoa mitchilli - Bay Anchovy Anchoa hepsetus - Striped Anchovy Anchoa cubana - Cuban Anchovy Anchoa lyolepis - Dusky Anchovy Anchoviella perfasciata - Flat Anchovy We are not aware of any other common names applied to this family, except for calling all of them anchovies. But as we have learned, each species has its own scientific (Latin) name which actually means something (please refer to The Meanings of the Scientific Names of Anchovies, page 9) along with an American Fisheries Society-accepted common name (Table 1; Page et al. 2013). Anchovies from large schools of fishes that feed on zooplankton. In North Carolina they may be found in all coastal basins, nearshore, and offshore (Tracy et al. 2020; NCFishes.com [Please note: Tracy et al. (2020) may be downloaded for free at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss60/1.] All species are found in saltwater environments (Maps 1-6), but Bay Anchovy is a seasonal freshwater inhabitant in our coastal rivers as far upstream as near Lock and Dam No. -

Anchoa Mitchilli) Eggs and Larvae in Chesapeake Bay ) E.W

Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 60 (2004) 409e429 www.elsevier.com/locate/ECSS Distribution and transport of bay anchovy (Anchoa mitchilli) eggs and larvae in Chesapeake Bay ) E.W. North , E.D. Houde1 University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, USA Received 28 February 2003; accepted 8 January 2004 Abstract Mechanisms and processes that influence small-scale depth distribution and dispersal of bay anchovy (Anchoa mitchilli) early-life stages are linked to physical and biological conditions and to larval developmental stage. A combination of fixed-station sampling, an axial abundance survey, and environmental monitoring data was used to determine how wind, currents, time of day, physics, developmental stage, and prey and predator abundances interacted to affect the distribution and potential transport of eggs and larvae. Wind-forced circulation patterns altered the depth-specific physical conditions at a fixed station and significantly influenced organism distributions and potential transport. The pycnocline was an important physical feature that structured the depth distribution of the planktonic community: most bay anchovy early-life stages (77%), ctenophores (72%), copepod nauplii (O76%), and Acartia tonsa copepodites (69%) occurred above it. In contrast, 90% of sciaenid eggs, tentatively weakfish (Cynoscion regalis), were found below the pycnocline in waters where dissolved oxygen concentrations were !2.0 mg lÿ1. The dayenight cycle also influenced organism abundances and distributions. Observed diel periodicity in concentrations of bay anchovy and sciaenid eggs, and of bay anchovy larvae O6 mm, probably were consequences of nighttime spawning (eggs) and net evasion during the day (larvae). Diel periodicity in bay anchovy swimbladder inflation also was observed, indicating that larvae apparently migrate to surface waters at dusk to fill their swimbladders. -

~;R:~

WOODS HOLE I.ABrnATORY REFERENCE rx:x:UMENT NUMBER 84-36 FOOD OF WEAKFISH IN COASTAL WATERS BE'IWEEN CAPE COD AND CAPE FEAR William L. Michaels .,~;r:~ (APPJtOy;t4G OfftaAL) I 12 J ·~<f~~ {li4tel National Marine Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Center Woods Hole Laboratory Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 USA Decanber 1984 JUL 29 7985 ABS'IRACT Stomach contents of 359 weakfish Cynoscion regalis were collected during Northeast Fisheries Center (NEFC) bottcm trawl surveys durirg' the sprirg, stnnmer, and auttnnn of 1978 through 1980. '!he study area included the coastal waters between Cape Fear am Cape Cod with bottom depths greater or equal than 6 meters. Weakfish fed primarily on schoolirg fish, except for juveniles (under 21 an FL) v.hich depended almost exclusively on mysid shrimp, namely Necmysis americana. Anchovies, especially bay anchovies, were the single most important fish prey of -weakfish. Although menhaden and other cl upeids were reported as a staple food of weakfish in nearshore and estuarine waters (ie. waters with depths less than 6 meters), these species were of little importance to weakfish in this stooy area. The results also sho-wed weakfisn to occassionally feed on decapod shrimp, crabs, squid, and rarely polychaete wonns. Dietary differences were evident according to the geographic area, season, and year. This variability seems related to fluctuations in distribution and abundance of both predator and prey. Weakfish fed primarily between dusk and dawn. Page 1 INTRODUCTION The weakfish@ Cynoscion regal is, also known as squeteague or gray seatrout, is a member of the drum family Sciaenidae (Fig. 1). -

Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Summer 2016 Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Linardich, Christi. "Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes" (2016). Master of Science (MS), Thesis, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/hydh-jp82 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES by Christi Linardich B.A. December 2006, Florida Gulf Coast University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BIOLOGY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2016 Approved by: Kent E. Carpenter (Advisor) Beth Polidoro (Member) Holly Gaff (Member) ABSTRACT HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Kent E. Carpenter Understanding the status of species is important for allocation of resources to redress biodiversity loss. -

Chesapeake Bay Species Habitat Literature Review

Chesapeake Bay Species Habitat Literature Review December 31, 2015 Bob Murphy Sam Stribling 1 Table of Contents Atlantic Silverside (Menidia menidia)……………………………………………...……. 3 Bay Anchovy (Anchoa mitchilli)………………………………………………..……….. 5 Black Sea Bass (Cenropristis striata)……………………………………………...…….. 8 Chain Pickerel (Esox niger)………………………………………………………..…… 11 Eastern Elliptio (Elliptio complanata)…………………………………………..…….... 13 Eastern Floater (Pyganodon cataracta) ………………………………………............... 15 Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides)………………………………….............…. 17 Macoma (Macoma balthica)……………………………………………………...…..… 19 Potomac Sculpin (Cottus Girardi)…………………………………………………...…. 21 Selected Anodontine Species: Dwarf Wedgemussel (Alasmidonta heterodon), Green Floater (Lasmigona subviridis), and Brook Floater (Alasmidonia varicosa)…..... 23 Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu)………………………………………...…… 25 Spot (Leiostomus xanthurus)…………………………………………………………… 27 Summer Flounder (Paralichthys dentatus)…………………………………………...… 30 White Perch (Morone Americana)……………………………………………………… 33 Purpose: The Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team (Fisheries GIT) of the Chesapeake Bay Program was allocated Tetra Tech (Tt) time to support Management Strategies under the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Agreement. The Fish Habitat Action Team under the Fisheries GIT requested Tt develop a detailed literature review for lesser- studied species across the Chesapeake Bay. Fish and shellfish in the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed rely on a variety of important habitats throughout -

Teleostei, Clupeiformes)

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Fall 2019 Global Conservation Status and Threat Patterns of the World’s Most Prominent Forage Fishes (Teleostei, Clupeiformes) Tiffany L. Birge Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Birge, Tiffany L.. "Global Conservation Status and Threat Patterns of the World’s Most Prominent Forage Fishes (Teleostei, Clupeiformes)" (2019). Master of Science (MS), Thesis, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/8m64-bg07 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS AND THREAT PATTERNS OF THE WORLD’S MOST PROMINENT FORAGE FISHES (TELEOSTEI, CLUPEIFORMES) by Tiffany L. Birge A.S. May 2014, Tidewater Community College B.S. May 2016, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BIOLOGY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December 2019 Approved by: Kent E. Carpenter (Advisor) Sara Maxwell (Member) Thomas Munroe (Member) ABSTRACT GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS AND THREAT PATTERNS OF THE WORLD’S MOST PROMINENT FORAGE FISHES (TELEOSTEI, CLUPEIFORMES) Tiffany L. Birge Old Dominion University, 2019 Advisor: Dr. Kent E. -

Species Habitat Matrix

Study reference Fish/shellfish Habitat Requirements Threat/Stressor Fish/Habitat species Response Type DO Temp Salinity Direct Indirect Species 1 – Elliptio complanata Bogan and Proch Eastern elliptio Permanent 1997, Cummings body of and Cordeiro 2011, water: large Strayer 1993; rivers, small USACE 2013 streams, canals, reservoirs, lakes, ponds Harbold et al. Eastern elliptio Presence of Environmental Diminished 2014; LaRouche fish host stressors on fish reproductive 2014; Lellis et al. species species, success; local 2013; Watters (American eel migratory extirpation 1996 [Anguilla blockages rostrata], Brook trout [Salvelinus fontinalis], Lake trout [S. namaycush], Slimy sculpin [Cottus cognatus], and Mottled sculpin [C. bairdii]) Sparks and Strayer Eastern elliptio Rivers Interstitial Reduced Behavioral stress 1998 (juveniles) DO > 2-4 dissolved responses mg/L oxygen caused (surfacing, gaping, by extending siphons sedimentation, and foot), increased Study reference Fish/shellfish Habitat Requirements Threat/Stressor Fish/Habitat species Response Type DO Temp Salinity Direct Indirect nutrient exposure to loading, organic predation inputs, or high temperatures Gelinas et al. 2014 Eastern elliptio Freshwater Harmful algal Compromised blooms, algal immune system, toxins reduced fitness Ashton 2009 Eastern elliptio Multiple 20-24°C Land cover Decreased environment conversion in frequency of al variables upstream observation, lower (pH, mean drainage area, numbers of daily water elevated individuals temperature, nutrients, conductivity, acidification, -

Anchoa Trinitatis (Fowler, 1915) EAK Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page Clupeiformes: Engraulidae 781 Anchoa trinitatis (Fowler, 1915) EAK Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Trinidad anchovy; Fr - Anchois machète; Sp - Anchoa machete. Diagnostic characters: Body fusiform, strongly compressed. Snout pointed; posterior tip of maxilla pointed, reaching beyond anterior margin of preoperculum, almost to gill opening; jaw teeth small. Pseudobranch shorter than eye. Lower gill rakers 13 to 21;gill cover canals of panamensis-type.Dorsal-fin origin slightly nearer to posterior margin of eye than to caudal-fin base; anal fin with 26 to 30 branched rays, its origin about at vertical through midpoint of dorsal-fin base. Anus advanced, opening nearer to pel- vic-fin tips than to anal-fin origin. Colour: dorsum blue-green, with distinct and fairly broad midlateral silver stripe; fins hyaline, but dark pigmentation at bases of anal and caudal fins. Size: Maximum 14 cm total length, commonly to 12 cm total length. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Shallow coastal waters, especially abundant in man- grove-lined lagoons. Sometimes captured very close to the bottom over soft sediments. Often forms large schools. Caught with seine nets. Marketed fresh, but mainly used as bait. No spe- cial fishery; not very suitable as a foodfish be- cause of its strongly compressed body.Separate statistics are not reported for this species. Distribution: Northern coasts of Colombia and Venezuela, and Trinidad. 782 Bony Fishes Anchovia clupeoides (Swainson, 1839) AHU Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: Engraulis productus Poey, 1866; Anchovia nigra Schultz, 1949 / None. FAO names: En - Zabaleta anchovy; Fr - Anchois hachude; Sp - Anchoa bocona. Diagnostic characters: Body fusiform, fairly compressed. -

Coilia Dussumieri Valenciennes, 1848 at Ye River Estuary, Southern Mon Coastal Water

Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology Research Article Open Access Early life distribution of gold spotted grenadier anchovy Coilia dussumieri valenciennes, 1848 at ye river estuary, southern mon coastal water Abstract Volume 7 Issue 2 - 2018 The pattern of the use of the Ye River Estuary, euryhaline area in southern Mon coastal water, by Coilia dussumieri was investigated to assess spawning period, recruitment and Naung Naung Oo to detect spatial-temporal patterns of this major fishery resource. Fishes were sampled Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, by seine nets, from early premonsoon, 2013 to postmonsoon, 2014 and by beach seine, Myanmar from premonsoon, 2013 to postmonsoon, 2015. Reproductive season, measured in terms of GSI, gonad development and appearance of recruits, indicate that reproduction occurs Correspondence: Naung Naung Oo, Assistant Lecturer, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, from August to March, when they reach the best condition. Recruitment peaks in post and Myanmar, Email [email protected] pre-monsoon at sandy beaches where they stay until early monsoon, moving toward deeper estuary areas during late monsoon. After that, they join adults and perform movements Received: March 24, 2018 | Published: April 25, 2018 between the estuary and the adjacent continental shelf to reproduce. Keywords: anchovies, condition, Engraulidae, recruitment, reproduction Introduction spawning period was related to the juvenile recruitment at sandy beaches, 3) to know the early life stages were assessed to detect Fishes of the Engraulidae family, known as anchovies, are widely eventual spatial-temporal pattern, and 4) to examine the length 1 distributed in tropical and sub-tropical waters. Most anchovies frequency distribution of C.