Scope of Survey & Relevant Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORRIS FREEWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by the City of Norris, Tennessee June 2020 SECTION 1: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION

NORRIS FREEWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by the City of Norris, Tennessee June 2020 SECTION 1: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION Location. Norris Freeway is located in the heart of the eastern portion of the Tennessee Valley. The Freeway passes over Norris Dam, whose location was selected to control the flooding caused by heavy rains in the Clinch and Powell River watershed. Beside flood control, there were a range of conditions that were to be addressed: the near absence of electrical service in rural areas, erosion and 1 landscape restoration, and a new modern road leading to Knoxville (as opposed to the dusty dirt and gravel roads that characterized this part of East Tennessee). The Freeway starts at US 25W in Rocky Top (once known as Coal Creek) and heads southeast to the unincorporated community of Halls. Along the way, it crosses Norris Dam, runs by several miles of Norris Dam State Park, skirts the City of Norris and that town’s watershed and greenbelt. Parts of Anderson County, Campbell County and Knox County are traversed along the route. Date of Local Designation In 1984, Norris Freeway was designated as a Tennessee Scenic Highway by the Tennessee Department of Transportation. Some folks just call such routes “Mockingbird Highways,” as the Tennessee State Bird is the image on the signs designating these Scenic Byways. Intrinsic Qualities Virtually all the intrinsic qualities come into play along Norris Freeway, particularly Historic and Recreational. In fact, those two characteristics are intertwined in this case. For instance, Norris Dam and the east side of Norris Dam State Park are on the National Register of Historic Places. -

Download Nine Lakes

MELTON HILL LAKE NORRIS LAKE - 809 miles of shoreline - 173 miles of shoreline FISHING: Norris Lake has over 56 species of fish and is well known for its striper fishing. There are also catches of brown Miles of Intrepid and rainbow trout, small and largemouth bass, walleye, and an abundant source of crappie. The Tennessee state record for FISHING: Predominant fish are musky, striped bass, hybrid striped bass, scenic gorges Daniel brown trout was caught in the Clinch River just below Norris Dam. Striped bass exceeding 50 pounds also lurk in the lake’s white crappie, largemouth bass, and skipjack herring. The state record saugeye and sandstone Boone was caught in 1998 at the warmwater discharge at Bull Run Steam Plant, which bluffs awaiting blazed a cool waters. Winter and summer striped bass fishing is excellent in the lower half of the lake. Walleye are stocked annually. your visit. trail West. is probably the most intensely fished section of the lake for all species. Another Nestled in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains, about 20 miles north of Knoxville just off I-75, is Norris Lake. It extends 1 of 2 places 56 miles up the Powell River and 73 miles into the Clinch River. Since the lake is not fed by another major dam, the water productive and popular spot is on the tailwaters below the dam, but you’ll find both in the U.S. largemouths and smallmouths throughout the lake. Spring and fall crappie fishing is one where you can has the reputation of being cleaner than any other in the nation. -

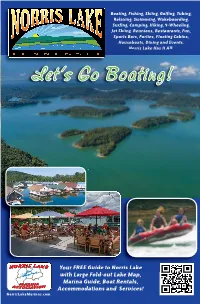

Let's Go Boating!

Boatinging, Fishingishing, Skiingiing, GolfingGolfing, TTuubingbing, RelaxingRelaxing, Swimming, Wakeboardingarding, SurfingSurfing, CCaampingmping,, Hiking, 4-WheelingWheeling, JetJet Skiingiing, Reunions,Reunions, ResResttaauurraantnts, Fun, SportSportss Bars, PartPartiies,es, FloatFlF oatiingng Cabins,bins, Housebouseboatoatss,, DiningDining andand Evenenttss. NNoorrrris LakLake HHaass It All!Alll! Let’s Go Boating! Your FREEREE GuideG id tto Norrisi Lake with Large Fold-out Lake Map, Marina Guide, Boat Rentals, Accommodations and Services! NorrisLakeMarinas.com Relax...Rejuvenate...Recharge... There is something in the air Come for a Visit... on beautiful Norris Lake! The serene beauty and clean Stay for a Lifetime! water brings families back year after year. We can accommodate your growing family or group of friends with larger homes! Call or book online today and start making Memories that last a lifetime. See why Norris Lake Cabin Rentals is “Tennessee’s Best Kept Secret” Kathy Nixon VLS# 423 Norris Lake Cabin Rentals Premium Vacation Lodging 3005 Lone Mountain Rd. New Tazewell, TN 37825 888-316-0637 NorrisLakeCabinRentals.com Welcome to Norris Lake Index 5 Norris Lake Dam 42 Floating Cabins on Norris Lake 44-45 Flat Hollow Marina & Resort 7 Norris Dam Area Clinch River West, Big Creek & Cove Creek 47 Blue Springs Boat Dock 9 Norris Dam Marina 49 Clinch River East Area 11 Sequoyah Marina Clinch River from Loyston Point to Rt 25E 13 Stardust Marina Mill Creek, Lost Creek, Poor Land Creek, and Big Sycamore Creek The Norris Lake Marina Association (NLMA) would like to welcome you 14 Fishing on Norris Lake 50 Watersports on Norris Lake to crystal-clear Norris Lake Tennessee where there are unlimited 17 Mountain Lake Marina and 51 Waterside Marina water-related recreational activities waiting for you in one of Tennessee Campground (Cove Creek) Valley Authority’s (TVA) cleanest lakes. -

Birds of Norris Dam State Park 125 Village Green Circle, Lake City, Tennessee 37769 / 800 543-9335

Birds of Norris Dam State Park 125 Village Green Circle, Lake City, Tennessee 37769 / 800 543-9335 Waterfowl, great blue and green herons, gulls, osprey and bald eagle frequent the lake, and the forests harbor great numbers of migratory birds in the spring and fall. Over 105 species of birds have been observed throughout the year. Below the dam look for orchard and northern orioles, eastern bluebirds, sparrows and tree swallows. Responsible Birding - Do not endanger the welfare of birds. - Tread lightly and respect bird habitat. - Silence is golden. - Do not use electronic sound devices to attract birds during nesting season, May-July. - Take extra care when in a nesting area. - Always respect the law and the rights of others, violators subject to prosecution. - Do not trespass on private property. - Avoid pointing your binoculars at other people or their homes. - Limit group sizes in areas that are not conducive to large crowds. Helpful Links Tennessee Birding Trails Photo by Scott Somershoe Scott by Photo www.tnbirdingtrail.org Field Checklist of Tennessee Birds www.tnwatchablewildlife.org eBird Hotspots and Sightings www.ebird.org Tennessee Ornithological Society www.tnstateparks.com www.tnbirds.org Tennessee Warbler Tennessee State Parks Birding www.tnstateparks.com/activities/birding Additional Nearby State Park Birding Opportunities Big Ridge – Cabins, Campground / Maynardville, TN 37807 / 865-471-5305 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/big-ridge Cove Lake – Campground, Restaurant / Caryville, TN 37714 / 423-566-9701 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/cove-lake Frozen Head – Campground / Wartburg, Tennessee 37887 / 423-346-3318 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/frozen-head Seven Islands – Boat Ramp / Kodak, Tennessee 37764 / 865-407-8335 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/seven-islands Birding Locations In and Around Norris Dam State Park A hiking trail map is available at the park. -

Floristic Notes on Plankton Algae of Norris Lake (Tennessee, USA)

Preslia, Praha, 73: 121- 126, 2001 121 Floristic notes on plankton algae of Norris Lake (Tennessee, USA) Floristicke nalezy planktonnich fas udolni prehrady Norris Lake (Tennessee, USA) 1 2 3 Tomas Ka 1 i n a , Patricia L. W a 1 n e & V aclav H o u k 1 Department of Botany, Charles University, Benatskti 2, CZ-128 OJ Praha 2, Czech Re public,· 2 Department of Botany, 437 Hesler Biology Building, University of Tennessee, Knoxville 3 7996-1100, Tennessee, USA,· 3 Prague Water Supply and Sewerage Company, Podolskti 15, CZ-147 00 Praha 4, Czech Republic Kalina T., Walne P. L. & Houk V. (2001): Floristic notes on plankton algae ofNorris Lake (Tennessee, USA). - Prestia, Praha, 73 : 121 - 126. Centric diatoms, silica-scaled chrysophytes and a desmid, Gonatozygon monotaenium, are the dominant components of the plankton algal community developed in autumn, 1998, in the Norris Lake (Tennessee, USA). This is the first and preliminary contribution to the Norris Lake phytoplankton. Keywords : Phytoplankton, centric diatoms, desmid, Norris Lake, Tennessee, USA Basic information about the Norris Lake Norris Lake is located about 30 miles north-west from Knoxville, Tennesee. It was created in 1936 by the damming of the Clinch River, one of the main tributaries of the Tennessee River, on the border of two counties, Union and Campbell. As a project of Tennessee Val ley Authority it serves both as a water reservoir and for recreational activities. The surface area varies between summer and winter as it is intentionally drained in winter to provide room for spring floods or rains. -

Of Tennessee Boating Laws and Responsibilities

of Tennessee Boating Laws and Responsibilities SPONSORED BY 2021 EDITION Copyright © 2021 Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC and its divisions and partners, www.kalkomey.com Published by Boat Ed®, a division of Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC, 740 East Campbell Road, Suite 900, Richardson, TX 75081, 214-351-0461. Printed in the U.S.A. Copyright © 2001–2021 by Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any process without permission in writing from Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC. Effort has been made to make this publication as complete and accurate as possible. All references contained in this publication have been compiled from sources believed to be reliable, and to represent the best current opinion on the subject. Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC is not responsible or liable for any claims, liabilities, damages, or other adverse effects or consequences to any person or property caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly from the application or use of the information contained in this publication. P0321-DP0921 www.kalkomey.com Copyright © 2021 Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC and its divisions and partners, www.kalkomey.com of Tennessee Boating Laws and Responsibilities Disclaimer: This publication is NOT a legal document. It is a summary of Tennessee’s current boating safety rules and regulations at the time of printing. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. -

Take It to the Bank: Tennessee Bank Fishing Opportunities Was Licenses and Regulations

Illustrations by Duane Raver/USFWS Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency ke2it2to2the2nkke2it2to2the2nk TennesseeTennessee bankbank fishingfishing opportunitiesopportunities Inside this guide Go fish!.......................................................................................1 Additional fishing opportunities and information..........6 Take it to the Bank: Tennessee Bank Fishing Opportunities was Licenses and regulations........................................................1 Additional contact agencies and facilities.....................6 produced by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and Tennes- Bank fishing tips........................................................................2 Water release schedules..........................................................6 see Technological University’s Center for the Management, Utilization Black bass..................................................................................2 Fishing-related Web sites.................................................... ....6 and Protection of Water Resources under project 7304. Development Sunfish (bream).........................................................................2 How to read the access tables.................................................7 of this guide was financed in part by funds from the Federal Aid in Sportfish Restoration Crappie..................................................................3 Access table key........................................................................7 (Public Law 91-503) as documented -

Norris Lake Cedar Grove Marina & Campground

May 2017 FREE! WWW.TNFHG.COM - Full Color On The Web! FREE MORE FACTS, PHOTOS, AND FUN INSIDE! FREE TENNESSEE FISHING & HUNTING GUIDE 1805 Amarillo Ln Knoxville, TN 37922 865-693-7468 J.L. & Lin Stepp Publishers “Serving Tennessee Since 1990” Our E-mail: [email protected] BENTON SHOOTERS SUPPLY Send us your pictures! The Largest Shooters Supply Store In The South! ABOUT THE COVER WWW.BENTONSHOOTERS.COM 423-338-2008 Cheryl Leonard displays a 6.02 lb largemouth Hwy 411, Benton, TN 37307 Mon - Sat 9am - 6pm bass caught in Watauga Lake. Spring is in full HUNTING & FISHING SUPPLIES - GUNS - AMMO swing and the fish are ARCHEREY EQUIPMENT - SAFES biting in Tennessee lakes OUTDOOR CLOTHING FOR MEN/WOMEN/CHILDREN - so why not take the family out to a favorite Tennessee lake this month for a weekend of fun! Cover photo courtesy TNT Outdoors, Mounain City, TN 423-727-4181 Fish & Hunt Tennessee! Long guns and handguns: Over 2,000 guns in stock! Ammo and supplies for every shooting need. Introduce A Kid To Fishing! KEEP OUR TENNESSEE 2 LAKES CLEAN WATTS BAR LAKE 4 CORNERS MARKET Intersection of Hwys 58 & 68, Decatur, TN * Gotzza Pizza - Subs - Salad - Wings (Delicious & Best @ Prices) Call In or Carry Out * Hunting & Fishing Licenses * Live Bait & Fishing Supplies * Cigarettes - Beer - Groceries * 100% Ethanol-Free Gas (grades 87 & 93) OPEN 7 DAYS - Big Game Checking Station 423-334-9518 Turkey season off to good start gor this hunter. Photo courtesy 4 Corners Market. * Groceries * Deli - Take-Out * Pizza * 100% Gas - no ethanol * Live Bait * Worms * Beer * Ice * Lottery * Propane * Minnows J & S Pawn Shop 1008 River Road, Decatur, TN 37322 (423) 334-3468 * New & Used Guns & Ammo * Gun Accessories Turkey hunting - a family affair! * We buy gold and silver Photo courtesy 4 Corners Market. -

Radioactive Waste Dilution in the Clinch River Eastern Tennessee

Radioactive Waste Dilution in the Clinch River Eastern Tennessee GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 433-G Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Radioactive Waste Dilution in the Clinch River Eastern Tennessee By P. H. CARRIGAN, JR. TRANSPORT OF R AD IONUCL I D E S BY STREAMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 433-G Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1968 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 25 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ___________________________ Gl Results of statistical analyses G5 Introduction _ _______________________ 1 Minimum, mean, and maximum daily dilution Acknowledgments ______________________ 3 factors 5 Streamflow characteristics of Whiteoak Creek and the Probability of equaling or exceeding Clinch River _______________________ 3 specified dilution factors 5 Dilution factor _______________________ 4 Seasonal variations in dilution _ 6 Computation of dilution factors ____________ 4 Frequency studies of minimum dilution factors 7 Selected period of record ______________ 4 Effects of diffusion in the Clinch River on dilution __ 7 Extension of discharge records for Conclusions ___ _ ___ _ 8 Whiteoak Creek ___________________ 4 References ____ ___ _ 9 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Index map of lower Clinch River basin ______________________________ _ G2 2. Graph showing flows in Whiteoak Creek and Clinch River during 1951, indicating variations in the river's dilution of radioactive releases ___________________________________ _ 3 3. -

Bank Fishing

Bank Fishing The following bank fishing locations were compiled by 4. Fish are very sensitive to sounds and shadows and can TWRA staff to inform anglers of areas where you can fish see and hear an angler standing on the bank. It is good without a boat. The types of waters vary from small ponds to fish several feet back from the water’s edge instead and streams to large reservoirs. You might catch bluegill, of on the shoreline and move quietly, staying 20 to 30 bass, crappie, trout, catfish, or striped bass depending on feet away from the shoreline as you walk (no running) the location, time of year, and your skill or luck. from one area to the other. Point your rod towards the All waters are open to the public. Some locations are sky when walking. Wearing clothing that blends in privately owned and operated, and in these areas a fee is re- with the surroundings may also make it less likely for quired for fishing. It is recommended that you call ahead if fish to be spooked. you are interested in visiting these areas. We have included 5. Begin fishing (casting) close and parallel to the bank these fee areas, because many of them they are regularly and then work out (fan-casting) toward deeper water. stocked and are great places to take kids fishing. If you’re fishing for catfish, keep your bait near the bottom. Look around for people and obstructions Bank Fishing Tips before you cast. 1. Fish are often near the shore in the spring and fall. -

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Powell River Area Claiborne and Union Counties Tennessee I by ARNOLD L

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Powell River Area Claiborne and Union Counties Tennessee i By ARNOLD L. BROKAW, JOHN RODGERS, DEANE F. KENT, ROBERT A. LAURENCE, and CHARLES H. BEHRE, JR. M <* CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1222-C UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS r _____________ Page Abstract. __________-________-__________----_--____-----______-___ Cl Introduction- _____________________________________________________ 2 Geologic investigations in the area----_-----___-_-_____-___-____- 2 Acknowledgments. ______________-_-----____---_-_-___-________ 3 General geology. ______________-_____-_-_--_-----_---_--------_____ 3 ^ Stratigraphy ______________________________________________________ 4 Cambrian rocks.---- ______________-------- _ __________________ 4 Nolichucky Shale_______.__----__- __ _____________________ 4 Maynardville Limestone Member_______-_______________. 4 Copper Ridge Dolomite. ________ _______ _ _____-_._ 4 Ordovician rocks----------_-__-------- --------_--------------_ 5 * Chepultepec Dolomite.-.------- __ ________________________ 5 Longview Dolomite. -__--. -___--__-__--__------_--_-_--____ 6 Kingsport Limestone.--..------- _ ..________-_-______-_____ 6 Mascot Dolomite-_--_--___-_--_-----------------_-_------- 7 Chickamauga Limestone.--.-------- -

Tennessee Striped Bass Newsletter

July/August 2020 Keith Shannon with a little Watts Bar striper…. August monthly meeting scheduled Tuesday, August 4th at 7pm at Louis’ Restuarant TSBA web site http://tnstripedbass.com/ for the latest news. Submit news items to [email protected] Join us on Facebook Tennessee Striped Bass Association Meetings resume in August We will have a club meeting on Tuesday, August 4th at Louis’ Restaurant at 4661 Old Broad- way, Knoxville, TN 37918. Dinner at 6pm; meeting at 7pm. This will be our first meeting since February, and we look forward to seeing you there! Unfortunately Mike Smith from the Eagle Bend Fish Hatchery, who was slated to be the guest speaker, will not be able to attend. Instead we will have an open forum on late-summer striper tactics. Be aware that Knoxville does have a mask mandate for anyone 12 or older in all public spaces including restaurants. Seeking a Permanent Meeting Location We have chosen a location for the August meeting, but we are still seeking suggestions for a permanent meeting location. Please reply on our Facebook page or email Keith Shannon at [email protected] with your ideas. Cory Malaby with a Watts Bar striper while fishing solo! 2 3 Tailwater Fishing for Striped Bass Much of the finest striped bass fishing in Tennessee occurs in tailwater portions of rivers, immediately downstream of hydroelectric dams. Many anglers associate tailwater striper fishing only with the spring, when fish run out of the main bodies of the reservoirs to spawn near the dams. However, stripers can be caught at the dams all year.