Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

State Water Control Board Page 1 O F16 9 Vac 25-260-350 and 400 Water Quality Standards

STATE WATER CONTROL BOARD PAGE 1 O F16 9 VAC 25-260-350 AND 400 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS 9 VAC 25-260-350 Designation of nutrient enriched waters. A. The following state waters are hereby designated as "nutrient enriched waters": * 1. Smith Mountain Lake and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 2. Lake Chesdin from its dam upstream to where the Route 360 bridge (Goodes Bridge) crosses the Appomattox River, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter between the dam and the Route 360 bridge; 3. South Fork Rivanna Reservoir and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 4. New River and its tributaries, except Peak Creek above Interstate 81, from Claytor Dam upstream to Big Reed Island Creek (Claytor Lake); 5. Peak Creek from its headwaters to its mouth (confluence with Claytor Lake), including all tributaries to their headwaters; 6. Aquia Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 7. Fourmile Run from its headwaters to the state line; 8. Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 9. Little Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 10. Gunston Cove from its headwaters to the state line; 11. Belmont and Occoquan Bays from their headwaters to the state line; 12. Potomac Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 13. Neabsco Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 14. Williams Creek from its headwaters to its confluence with Upper Machodoc Creek; 15. Tidal freshwater Rappahannock River from the fall line to Buoy 44, near Leedstown, Virginia, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter the tidal freshwater Rappahannock River; 16. -

Final Development of Shenandoah River

SDMS DocID 2109708 Decision Rationale Total Maximum Daily Load of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) for the Shenandoah River, Virginia and West Virginia I. Introduction The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) be developed for those water bodies identified as impaired by the state where technology-based and other controls did not provide for attainment of water quality standards. A TMDL is a determination of the amount of a pollutant from point, nonpoint, and natural background sources, including a margin of safety, that may be discharged to a water qualit>'-limited water body. This document will set forth the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) rationale for establishing the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of PGBs for the Shenandoah River. EPA's rationale is based on the determination that the TMDL meets the following 8 regulatory conditions pursuant to 40 CFR §130. 1) The TMDL is designed to implement applicable water quality standards. 2) The TMDL includes a total allowable load as well as individual waste load allocations and load allocations. 3) The TMDL considers the impacts of background pollutant contributions. 4) The TMDL considers critical environmental conditions. 5) The TMDL considers seasonal environmental variations. 6) The TMDL includes a margin of safety. 7) The TMDL has been subject to public participation. 8) There is reasonable assurance that the TMDL can be met. II. Background The Shenandoah River drains 1,957,690 acres of land. The watershed can be broken down into several land-uses. Forest and agricultural lands make-up roughly 1,800,000 acres of watershed. -

Camping Places (Campsites and Cabins) with Carderock Springs As

Camping places (campsites and cabins) With Carderock Springs as the center of the universe, here are a variety of camping locations in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Delaware. A big round of applause to Carderock’s Eric Nothman for putting this list together, doing a lot of research so the rest of us can spend more time camping! CAMPING in Maryland 1) Marsden Tract - 5 mins - (National Park Service) - C&O canal Mile 11 (1/2 mile above Carderock) three beautiful group campsites on the Potomac. Reservations/permit required. Max 20 to 30 people each. C&O canal - hiker/biker campsites (no permit needed - all are free!) about every five miles starting from Swains Lock to Cumberland. Campsites all the way to Paw Paw, WV (about 23 sites) are within 2 hrs drive. Three private campgrounds (along the canal) have cabins. Some sections could be traveled by canoe on the Potomac (canoe camping). Closest: Swains Lock - 10 mins - 5 individual tent only sites (one isolated - take path up river) - all close to parking lot. First come/first serve only. Parking fills up on weekends by 8am. Group Campsites are located at McCoy's Ferry, Fifteen Mile Creek, Paw Paw Tunnel, and Spring Gap. They are $20 per site, per night with a maximum of 35 people. Six restored Lock-houses - (several within a few miles of Carderock) - C&O Canal Trust manages six restored Canal Lock-houses for nightly rental (some with heat, water, A/C). 2) Cabin John Regional Park - 10 mins - 7 primitive walk-in sites. Pit toilets, running water. -

Scenic Landforms of Virginia

Vol. 34 August 1988 No. 3 SCENIC LANDFORMS OF VIRGINIA Harry Webb . Virginia has a wide variety of scenic landforms, such State Highway, SR - State Road, GWNF.R(T) - George as mountains, waterfalls, gorges, islands, water and Washington National Forest Road (Trail), JNFR(T) - wind gaps, caves, valleys, hills, and cliffs. These land- Jefferson National Forest Road (Trail), BRPMP - Blue forms, some with interesting names such as Hanging Ridge Parkway mile post, and SNPMP - Shenandoah Rock, Devils Backbone, Striped Rock, and Lovers Leap, National Park mile post. range in elevation from Mt. Rogers at 5729 feet to As- This listing is primarily of those landforms named on sateague and Tangier islands near sea level. Two nat- topographic maps. It is hoped that the reader will advise ural lakes occur in Virginia, Mountain Lake in Giles the Division of other noteworthy landforms in the st& County and Lake Drummond in the City of Chesapeake. that are not mentioned. For those features on private Gaps through the mountains were important routes for land always obtain the owner's permission before vis- early settlers and positions for military movements dur- iting. Some particularly interesting features are de- ing the Civil War. Today, many gaps are still important scribed in more detail below. locations of roads and highways. For this report, landforms are listed alphabetically Dismal Swamp (see Chesapeake, City of) by county or city. Features along county lines are de- The Dismal Swamp, located in southeastern Virginia, scribed in only one county with references in other ap- is about 10 to 11 miles wide and 15 miles long, and propriate counties. -

Smith Creek Watershed Management Plan

Smith Creek Watershed Management Plan Smith Creek Watershed Management Plan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Smith Creek Planning Initiative Working Partners New Hanover County Planning City of Wilmington Planning City of Wilmington Stormwater Services New Hanover Soil and Water Conservation District UNCW Coastal Land Trust North Carolina Ecosystem Enhancement Program North Carolina Coastal Federation Cape Fear River Watch Watershed Management Advisory Board Members William Caster, New Hanover County Board of Commissioners Don Cooke, Progress Energy Carlton Fisher, Coastal Realty Company William F. Gage, Smith-Gage Architects Clark Hipp – Hipp + Best Architects John Jefferies – Jefferies & Faris Architects Brenda McDonald – First Mortgage Corporation Shelly Miller – New Hanover Soil and Water Conservation District Laura Padgett – Wilmington City Council Larry Sneeden – ESP Associates Watershed Management Advisory Board Technical Committee Members Shawn Ralston, New Hanover County Planning Department Phil Prete, City of Wilmington Planning Department Shelly Miller, New Hanover Soil and Water Conservation District Jennifer Butler, City of Wilmington Stormwater Services Nicole Miller, Airlie Gardens Environmental Education Program Matthew Collogan, Airlie Gardens Environmental Education Program Kristen Miguez, North Carolina Ecosystem Enhancement Program Mike Mallin, UNCW Center for Marine Sciences Nancy Preston, Coastal Land Trust Smith Creek Watershed Management Plan Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ -

Draft Environmental Assessment

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Lucky Minerals (Montana), Inc. Lucky Minerals Project, Park County, MT Exploration License Application #00795 Prepared by Montana Department of Environmental Quality Hard Rock Mining Bureau 1520 East Sixth Avenue PO Box 200901 Helena, MT 59620-0901 October 13, 2016 Table of Contents 1 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION ........................................................................................... 1 1.1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 PURPOSE AND NEED ............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 HISTORICAL MINING AND PREVIOUS EXPLORATION DISTURBANCE ................. 2 1.3.1 Emigrant Mining District Chronology (Geologic Systems Ltd., 2015) ....................... 2 1.3.2 St. Julian Claim Block ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4 PROJECT LOCATION............................................................................................................... 4 1.5 AUTHORIZING ACTION ........................................................................................................ 9 1.6 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ....................................................................................................... 9 1.6.1 SCOPING ........................................................................................................................... -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

2019 Trout Program Maps

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 FOUR DOLLARS Inside: 2019 Trout Program Maps SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 Contents 5 How Sweet Sweet Sweet It Is! By Mike Roberts With support from the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation, volunteers, and business partners, a citizen science project aims to help a magnificent songbird in the Roanoke River basin. 10 Hunting: A Foundation For Life By Curtis J. Badger A childhood spent afield gives the author reason to reflect upon a simpler time, one that deeply shaped his values. 14 Women Afield: Finally By John Shtogren There are many reasons to cheer the trend of women’s interest in hunting and fishing, and the outdoors industry takes note. 20 What’s Up With Cobia? By Ken Perrotte Virginia is taking a lead in sound management of this gamefish through multi-state coordination, tagging efforts, and citation data. 24 For The Love Of Snakes By David Hart Snakes are given a bad rap, but a little knowledge and the right support group can help you overcome your fears. 28 The Evolution Of Cute By Jason Davis Nature has endowed young wildlife with a number of strategies for survival, cuteness being one of them. 32 2019 Trout Program Maps By Jay Kapalczynski Fisheries biologists share the latest trout stocking locations. 38 AFIELD AND AFLOAT 41 A Walk in the Woods • 42 Off the Leash 43 Photo Tips • 45 On the Water • 46 Dining In Cover: A female prothonotary warbler brings caterpillars to her young. See page 5. ©Mike Roberts Left: A handsome white-tailed buck pauses while feeding along a fence line. -

Backpacking: Bird Knob

1 © 1999 Troy R. Hayes. All rights reserved. Preface As a new Scoutmaster, I wanted to take my troop on different kinds of adventure. But each trip took a tremendous amount of preparation to discover what the possibilities were, to investigate them, to pick one, and finally make the detailed arrangements. In some cases I even made a reconnaissance trip in advance in order to make sure the trip worked. The Pathfinder is an attempt to make this process easier. A vigorous outdoor program is a key element in Boy Scouting. The trips described in these pages range from those achievable by eleven year olds to those intended for fourteen and up (high adventure). And remember what the Irish say: The weather determines not whether you go, but what clothing you should wear. My Scouts have camped in ice, snow, rain, and heat. The most memorable trips were the ones with "bad" weather. That's when character building best occurs. Troy Hayes Warrenton, VA [Preface revised 3-10-2011] 2 Contents Backpacking Bird Knob................................................................... 5 Bull Run - Occoquan Trail.......................................... 7 Corbin/Nicholson Hollow............................................ 9 Dolly Sods (2 day trip)............................................... 11 Dolly Sods (3 day trip)............................................... 13 Otter Creek Wilderness............................................. 15 Saint Mary's Trail ................................................ ..... 17 Sherando Lake ....................................................... -

Smith Creek Watershed

Smith Creek Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay Showcase Watershed 43 percent of this intensively farmed watershed is agricultural land with significant amounts of cropland (5,713 acres) and hayland (13,105 acres). Supporting State Goals NRCS is partnering with more than 20 groups and organizations in the watershed to improve water quality and support the current Smith Creek Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plan. Best management practices to address resource concerns include installing riparian buffers, cover crops, rotational Overview Smith Creek Profile grazing and alternative watering systems; constructing waste storage In 2010, USDA’s Natural Resources The Shenandoah Valley is home to 75 facilities; excluding livestock from Conservation Service (NRCS) percent of Virginia’s poultry operations streams; and implementing nutrient established three showcase water- and approximately 46 percent of its management practices. sheds to demonstrate what can be dairies. This concentration of animal accomplished when people and groups farms has contributed to nitrogen, Smith Creek is the only small come together to solve natural resource phosphorus, sediment and bacteria agricultural watershed in Virginia where problems in a targeted area. pollution in local streams, the the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, is monitoring progress as BMPs are The goal of the project was to reduce and the Chesapeake Bay. installed. USGS collects river samples nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment from the Smith Creek watershed contributions from soil erosion, over- The Smith Creek Watershed covers application of nutrients, poor pasture 67,335 acres and includes four sub- management and uncontrolled animal watersheds: Dry Fork, Mountain Run, access to streams. -

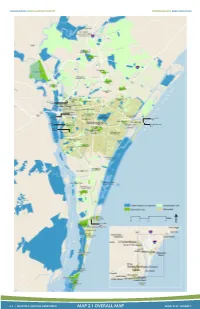

Map 2.1 Overall Map Move

WILMINGTON/NEW HANOVER COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE GREENWAY PLAN Northside Park Robert Strange Greensboro Park Park Optimist Johnnie Mercers Park Pier Legion Stadium Masonboro Island Coastal Resreve Snows Cut Park 2-5 | CHAPTER 2: EXISTING CONDITIONS MAP 2.1 OVERALL MAP MOVE. PLAY. CONNECT. WILMINGTON/NEW HANOVER COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE GREENWAY PLAN This map displays some highlights from comments collected during steering committee meetings that took place in early 2012. GE Wilmington employs more than 2,000 people in its Castle Hayne facility1. The University of North Carolina at Wilmington employs over 1,800 faculty and staff, teaching over 2 The Riverwalk is a scenic 13,000 students each year . boardwalk along the east bank of the Cape Fear River in downtown Wilmington. It provides a place to stroll along the water minutes from the buildings, restaurants, and Middle Sound Loop Rd. is a shops forming the heart of popular on-road recreation downtown. destination. The Forest Hills Loop is a popular walking and jogging destination just east of downtown. The loop is approximately three miles in length and passes by the Wilmington “The Loop” around Wrightsville Beach YMCA and Beaumont Park. is a popular walking and jogging destination near the ocean. The Loop is formed by a concrete sidewalk varying in width from 5’ to 10’ and passes by scenic views of the sound, as well as New Hanover Regional Medical by the shops and restaurants forming Center is a major economic driver the commercial district along Lumina in the region, with more than 4,000 Avenue. employees3. The shopping center at the junction of College Rd.