Flavin Oxidoreductase from Escherichia Coli with NADPH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Biochemical and Biophysical Characterisation of Anopheles Gambiae Nadph-Cytochrome P450 Reductase

BIOCHEMICAL AND BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISATION OF ANOPHELES GAMBIAE NADPH-CYTOCHROME P450 REDUCTASE Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by PHILIP WIDDOWSON SEPTEMBER 2010 0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people whom I would like to thank for their support during the completion of this thesis. Firstly, I would like to thank my family; Mum, Louise and Chris for putting up with me over the years and for their love, patience and, in particular to Chris, technical support throughout– I could not have coped on my own without all your help. I would like to extend special thanks to Professor Lu-Yun Lian for her constant supervision throughout my Ph.D. She always kept me on the right path and was always available for support and advice which was especially useful when things were not going to plan. Thank you for all your help. In addition to Professor Lian I would like to thank all the members of the Structural Biology Group and everybody, past and present, whom I worked alongside in Lab C over the past four years. I would also like to thank the University of Liverpool for the funding that made all this possible. I would like to make particular mention to a few people in the School of Biological Sciences who were of particular help during my time at university. Dr. Mark Wilkinson was a constant support, not only during my Ph.D, but as my undergraduate tutor and honours project supervisor. Dr. Dan Rigden and Dr. -

Single-Molecule Spectroscopy Reveals How Calmodulin Activates NO Synthase by Controlling Its Conformational Fluctuation Dynamics

Single-molecule spectroscopy reveals how calmodulin activates NO synthase by controlling its conformational fluctuation dynamics Yufan Hea,1, Mohammad Mahfuzul Haqueb,1, Dennis J. Stuehrb,2, and H. Peter Lua,2 aCenter for Photochemical Sciences, Department of Chemistry, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403; and bDepartment of Pathobiology, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195 Edited by Louis J. Ignarro, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine, Beverly Hills, CA, and approved July 31, 2015 (received for review May 5, 2015) Mechanisms that regulate the nitric oxide synthase enzymes (NOS) this model, the FMN domain is suggested to be highly dynamic are of interest in biology and medicine. Although NOS catalysis and flexible due to a connecting hinge that allows it to alternate relies on domain motions, and is activated by calmodulin binding, between its electron-accepting (FAD→FMN) or closed confor- the relationships are unclear. We used single-molecule fluores- mation and electron-donating (FMN→heme) or open conforma- cence resonance energy transfer (FRET) spectroscopy to elucidate tion (Fig. 1 A and B)(28,30–36). In the electron-accepting closed the conformational states distribution and associated conforma- conformation, the FMN domain interacts with the NADPH/FAD tional fluctuation dynamics of the two electron transfer domains domain (FNR domain) to receive electrons, whereas in the elec- in a FRET dye-labeled neuronal NOS reductase domain, and to tron donating open conformation the FMN domain has moved understand how calmodulin affects the dynamics to regulate away to expose the bound FMN cofactor so that it may transfer catalysis. -

![View, the Catalytic Center of Bnoss Is Almost Identical to Mnos Except That a Conserved Val Near Heme Iron in Mnos Is Substituted by Iie[25]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8837/view-the-catalytic-center-of-bnoss-is-almost-identical-to-mnos-except-that-a-conserved-val-near-heme-iron-in-mnos-is-substituted-by-iie-25-78837.webp)

View, the Catalytic Center of Bnoss Is Almost Identical to Mnos Except That a Conserved Val Near Heme Iron in Mnos Is Substituted by Iie[25]

STUDY OF ELECTRON TRANSFER THROUGH THE REDUCTASE DOMAIN OF NEURONAL NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE AND DEVELOPMENT OF BACTERIAL NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE INHIBITORS YUE DAI Bachelor of Science in Chemistry Wuhan University June 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CLINICAL AND BIOANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY July 2016 We hereby approve this dissertation for Yue Dai Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical-Bioanalytical Chemistry Degree for the Department of Chemistry and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by Dennis J. Stuehr. PhD. Department of Pathobiology, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Mekki Bayachou. PhD. Department of Chemistry / July 8th 2016 Thomas M. McIntyre. PhD. Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Bin Su. PhD. Department of Chemistry / July 8th 2016 Jun Qin. PhD. Department of Molecular Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Student’s Date of Defense: July 8th 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to express my special appreciation and thanks to my Ph. D. mentor, Dr. Dennis Stuehr. You have been a tremendous mentor for me. It is your constant patience, encouraging and support that guided me on the road of becoming a research scientist. Your advices on both research and life have been priceless for me. I would like to thank my committee members - Professor Mekki Bayachou, Professor Bin Su, Dr. Thomas McIntyre, Dr. Jun Qin and my previous committee members - Dr. Donald Jacobsen and Dr. Saurav Misra for sharing brilliant comments and suggestions with me. I would like to thank all our lab members for their help ever since I joint our lab. -

Bioinorganic Chemistry of Nickel

inorganics Editorial Bioinorganic Chemistry of Nickel Michael J. Maroney 1,* and Stefano Ciurli 2,* 1 Department of Chemistry and Program in Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 240 Thatcher Rd. Life Sciences, Laboratory Rm N373, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 2 Laboratory of Bioinorganic Chemistry, Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology, University of Bologna, Viale G. Fanin 40, I-40127 Bologna, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.J.M.); [email protected] (S.C.) Received: 11 October 2019; Accepted: 11 October 2019; Published: 30 October 2019 Following the discovery of the first specific and essential role of nickel in biology in 1975 (the dinuclear active site of the enzyme urease) [1], nickel has become a major player in bioinorganic chemistry,particularly in microorganisms, having impacts on both environmental settings and human pathologies. At least nine classes of enzymes are now known to require nickel in their active sites, including catalysis of redox [(Ni,Fe) hydrogenases, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, methyl coenzyme M reductase, acetyl coenzyme A synthase, superoxide dismutase] and nonredox (glyoxalase I, acireductone dioxygenase, lactate isomerase, urease) chemistries. In addition, the dark side of nickel has been illuminated in regard to its participation in microbial pathogenesis, cancer, and immune responses. Knowledge gleaned from the investigations of inorganic chemists into the coordination and redox chemistry of this element have boosted the understanding of these biological roles of nickel in each context. In this issue, eleven contributions, including four original research articles and seven critical reviews, will update the reader on the broad spectrum of the role of nickel in biology. -

Cysteine Dioxygenase 1 Is a Metabolic Liability for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Authors: Yun Pyo Kang1, Laura Torrente1, Min Liu2, John M

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/459602; this version posted November 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Cysteine dioxygenase 1 is a metabolic liability for non-small cell lung cancer Authors: Yun Pyo Kang1, Laura Torrente1, Min Liu2, John M. Asara3,4, Christian C. Dibble5,6 and Gina M. DeNicola1,* Affiliations: 1 Department of Cancer Physiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA 2 Proteomics and Metabolomics Core Facility, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA 3 Division of Signal Transduction, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA 4 Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 5 Department of Pathology and Cancer Center, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA 6 Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA *Correspondence to: [email protected]. Keywords: KEAP1, NRF2, cysteine, CDO1, sulfite Summary NRF2 is emerging as a major regulator of cellular metabolism. However, most studies have been performed in cancer cells, where co-occurring mutations and tumor selective pressures complicate the influence of NRF2 on metabolism. Here we use genetically engineered, non-transformed primary cells to isolate the most immediate effects of NRF2 on cellular metabolism. We find that NRF2 promotes the accumulation of intracellular cysteine and engages the cysteine homeostatic control mechanism mediated by cysteine dioxygenase 1 (CDO1), which catalyzes the irreversible metabolism of cysteine to cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA). Notably, CDO1 is preferentially silenced by promoter methylation in non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) harboring mutations in KEAP1, the negative regulator of NRF2. -

Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Its Therapeutic Inhibition in Cancer George C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College | Bryn Mawr College... Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Chemistry Faculty Research and Scholarship Chemistry 2018 Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Its Therapeutic Inhibition in Cancer George C. Prendergast William Paul Malachowski Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Arpita Mondal Peggy Scherle Alexander J. Muller Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/chem_pubs Part of the Chemistry Commons Custom Citation George C. Prendergast, William J. Malachowski, Arpita Mondal, Peggy Scherle, and Alexander J. Muller. 2018. "Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Its Therapeutic Inhibition in Cancer." International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 336: 175-203. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/chem_pubs/25 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Its Therapeutic Inhibition in Cancer George C. Prendergast, William, Malachowski, Arpita Mondal, Peggy Scherle, and Alexander J. Muller International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 336: 175-203. http://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ircmb.2017.07.004 ABSTRACT The tryptophan catabolic enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) has attracted enormous attention in driving cancer immunosuppression, neovascularization, and metastasis. IDO1 suppresses local CD8+ T effector cells and natural killer cells and induces CD4+ T regulatory cells (iTreg) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). The structurally distinct enzyme tryptophan dioxygenase (TDO) also has been implicated recently in immune escape and metastatic progression. -

Cbic.202000100Taverne

Delft University of Technology A Minimized Chemoenzymatic Cascade for Bacterial Luciferase in Bioreporter Applications Phonbuppha, Jittima; Tinikul, Ruchanok; Wongnate, Thanyaporn; Intasian, Pattarawan; Hollmann, Frank; Paul, Caroline E.; Chaiyen, Pimchai DOI 10.1002/cbic.202000100 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in ChemBioChem Citation (APA) Phonbuppha, J., Tinikul, R., Wongnate, T., Intasian, P., Hollmann, F., Paul, C. E., & Chaiyen, P. (2020). A Minimized Chemoenzymatic Cascade for Bacterial Luciferase in Bioreporter Applications. ChemBioChem, 21(14), 2073-2079. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202000100 Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Green Open Access added to TU Delft Institutional Repository ‘You share, we take care!’ – Taverne project https://www.openaccess.nl/en/you-share-we-take-care Otherwise as indicated in the copyright section: the publisher is the copyright holder of this work and the author uses the Dutch legislation to make this work public. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Muscle Regeneration Controlled by a Designated DNA Dioxygenase

Wang et al. Cell Death and Disease (2021) 12:535 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03817-2 Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access Muscle regeneration controlled by a designated DNA dioxygenase Hongye Wang1, Yile Huang2,MingYu3,YangYu1, Sheng Li4, Huating Wang2,5,HaoSun2,5,BingLi 3, Guoliang Xu6,7 andPingHu4,8,9 Abstract Tet dioxygenases are responsible for the active DNA demethylation. The functions of Tet proteins in muscle regeneration have not been well characterized. Here we find that Tet2, but not Tet1 and Tet3, is specifically required for muscle regeneration in vivo. Loss of Tet2 leads to severe muscle regeneration defects. Further analysis indicates that Tet2 regulates myoblast differentiation and fusion. Tet2 activates transcription of the key differentiation modulator Myogenin (MyoG) by actively demethylating its enhancer region. Re-expressing of MyoG in Tet2 KO myoblasts rescues the differentiation and fusion defects. Further mechanistic analysis reveals that Tet2 enhances MyoD binding by demethylating the flanking CpG sites of E boxes to facilitate the recruitment of active histone modifications and increase chromatin accessibility and activate its transcription. These findings shed new lights on DNA methylation and pioneer transcription factor activity regulation. Introduction Ten-Eleven Translocation (Tet) family of DNA dioxy- 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; Skeletal muscles can regenerate due to the existence of genases catalyze the active DNA demethylation and play muscle stem cells (MuSCs)1,2. The normally quiescent critical roles in embryonic development, neural regen- MuSCs are activated after muscle injury and further dif- eration, oncogenesis, aging, and many other important – ferentiate to support muscle regeneration3,4. -

Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the Micropollutant

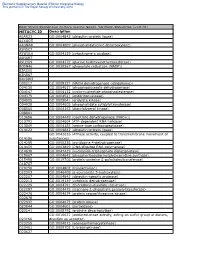

1 Relating Metatranscriptomic Profiles to the 2 Micropollutant Biotransformation Potential of 3 Complex Microbial Communities 4 5 Supporting Information 6 7 Stefan Achermann,1,2 Cresten B. Mansfeldt,1 Marcel Müller,1,3 David R. Johnson,1 Kathrin 8 Fenner*,1,2,4 9 1Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 8600 Dübendorf, 10 Switzerland. 2Institute of Biogeochemistry and Pollutant Dynamics, ETH Zürich, 8092 11 Zürich, Switzerland. 3Institute of Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zürich, 8092 12 Zürich, Switzerland. 4Department of Chemistry, University of Zürich, 8057 Zürich, 13 Switzerland. 14 *Corresponding author (email: [email protected] ) 15 S.A and C.B.M contributed equally to this work. 16 17 18 19 20 21 This supporting information (SI) is organized in 4 sections (S1-S4) with a total of 10 pages and 22 comprises 7 figures (Figure S1-S7) and 4 tables (Table S1-S4). 23 24 25 S1 26 S1 Data normalization 27 28 29 30 Figure S1. Relative fractions of gene transcripts originating from eukaryotes and bacteria. 31 32 33 Table S1. Relative standard deviation (RSD) for commonly used reference genes across all 34 samples (n=12). EC number mean fraction bacteria (%) RSD (%) RSD bacteria (%) RSD eukaryotes (%) 2.7.7.6 (RNAP) 80 16 6 nda 5.99.1.2 (DNA topoisomerase) 90 11 9 nda 5.99.1.3 (DNA gyrase) 92 16 10 nda 1.2.1.12 (GAPDH) 37 39 6 32 35 and indicates not determined. 36 37 38 39 S2 40 S2 Nitrile hydration 41 42 43 44 Figure S2: Pearson correlation coefficients r for rate constants of bromoxynil and acetamiprid with 45 gene transcripts of ECs describing nucleophilic reactions of water with nitriles. -

ALOX12 Antibody

Efficient Professional Protein and Antibody Platforms ALOX12 Antibody Basic information: Catalog No.: UPA60470 Source: Rabbit Size: 50ul/100ul Clonality: polyclonal Concentration: 1mg/ml Isotype: Rabbit IgG Purification: affinity purified by Protein A Useful Information: Applications: WB:1:500-2000 Reactivity: Human, Mouse, Rat, Cow Specificity: This antibody recognizes ALOX12 protein. KLH conjugated synthetic peptide derived from human 12 Lipoxygenase Immunogen: 101-200/663 Non-heme iron-containing dioxygenase that catalyzes the stereo-specific peroxidation of free and esterified polyunsaturated fatty acids generating a spectrum of bioactive lipid mediators. Mainly converts arachidonic acid to (12S)-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid/(12S)-HPETE but can also metabo- lize linoleic acid. Has a dual activity since it also converts leukotriene A4/LTA4 into both the bioactive lipoxin A4/LXA4 and lipoxin B4/LXB4. Description: Through the production of specific bioactive lipids like (12S)-HPETE it regu- lates different biological processes including platelet activation. It also probably positively regulates angiogenesis through regulation of the expres- sion of the vascular endothelial growth factor. Plays a role in apoptotic pro- cess, promoting the survival of vascular smooth muscle cells for instance. May also play a role in the control of cell migration and proliferation. {ECO:0000269|PubMed:16638750, Uniprot: P18054 Human BiowMW: 76 KDa Buffer: 0.01M TBS(pH7.4) with 1% BSA, 0.03% Proclin300 and 50% Glycerol. Storage: Store at 4°C short term and -20°C long term. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Note: For research use only, not for use in diagnostic procedure. Data: Gene Universal Technology Co. Ltd www.universalbiol.com Tel: 0550-3121009 E-mail: [email protected] Efficient Professional Protein and Antibody Platforms Sample: Raw264.7 Cell Lysate at 40 ug A431 Cell Lysate at 40 ug Primary: Anti-ALOX12 at 1/300 dilution Secondary: IRDye800CW Goat An- ti-Rabbit IgG at 1/20000 dilution Predicted band size: 73 kD Observed band size: 73 kD Gene Universal Technology Co.