4 Celebrification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

For Reel & Real

MAY 2016 CONFIDENTIAL Reigning Queens. Bb. Pilipinas International Kylie Versoza and Miss Universe Philippines Maxine Medina Maxine Medina is the new Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach MANILA - Reigning Miss Universe Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach relinquished the Bb. & Pilipinas-Universe crown to top model Maria Mika Maxine Medina at the Bb. Nadine Lustre Pilipinas 2016 Grand Coronation Night before a jam-packed crowd at the Smart Araneta Coliseum April 20. A stunning beauty from Quezon City, Medina, a 25-year-old, 5-foot-7 inte- rior designer and part-time model, was predicted to take the top title in this year’s Bb. PiIlipinas pageant, giving high hopes James Reid for a back-to-back Miss Universe crown. She had previously entered the com- FOR REEL & REAL petition in 2012 but backed out due to contract conflict issues. But the real star of the night was Wurtzbach who took a break from her hectic duties as Miss Universe to be in the country and crown her succes- MAXINE continued on page 25 Miss Philippines Canada 2016 Miss Philippines Canada 2015 Nathalie Ramos (CENTER) poses with the PCCF candidates for this year. Senator Tobias Enverga presents the cer- tificate of Recognition for Zenaida Guzman to her son Dr. Solon Guzman. Zenaida is currently in the Philippines. MAY 2016 MAY 2016 L. M. Confidential 1 2 L. M. Confidential MAY 2016 MAY 2016 KAPUSO STAR Tom This Is How Long Sex Usually Lasts We’re not saying you’ve peeked Rodriquez to star at through the blinds to see your neighbors doing the deed, but chances are you’ve wondered how your stamina stacks up against ev- Pinoy Fiesta eryone else. -

Pacnet Number 23 May 6, 2010

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 23 May 6, 2010 Philippine Elections 2010: Simple Change or True problem is his loss of credibility stemming from his ouster as Reform? by Virginia Watson the country’s president in 2001 on charges of corruption. Virginia Watson [[email protected]] is an associate Survey results for vice president mirror the presidential professor at the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies in race. Aquino’s running mate, Sen. Manuel Roxas, Jr. has Honolulu. pulled ahead with 37 percent. Sen. Loren Legarda, in her second attempt at the vice presidency, dropped to the third On May 10, over 50 million Filipinos are projected to cast spot garnering 20 percent, identical to the results of the their votes to elect the 15th president of the Philippines, a Nacionalista Party’s presidential candidate, Villar. Estrada’s position held for the past nine years by Gloria Macapagal- running mate, former Makati City Mayor Jejomar “Jojo” Arroyo. Until recently, survey results indicated Senators Binay, has surged past Legarda and he is now in second place Benigno Aquino III of the Liberal Party and Manuel Villar, Jr. with 28 percent supporting his candidacy. of the Nacionalista Party were in a tight contest, but two weeks from the elections, ex-president and movie star Joseph One issue that looms large is whether any of the top three Estrada, of the Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino, gained ground to contenders represents a new kind of politics and governance reach a statistical tie with Villar for second place. distinct from Macapagal-Arroyo, whose administration has been marked by corruption scandals and human rights abuses Currently on top is “Noynoy” Aquino, his strong showing while leaving the country in a state of increasing poverty – the during the campaign primarily attributed to the wave of public worst among countries in Southeast Asia according to the sympathy following the death of his mother President Corazon World Bank. -

![J. Leonen, En Banc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0526/j-leonen-en-banc-300526.webp)

J. Leonen, En Banc]

EN BANC G.R. No. 221697 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and ESTRELLA C. ELAMPARO, Respondents. G.R. No. 221698-700 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, FRANCISCO S. TATAD, ANTONIO P. CONTRERAS, and AMADO T. VALDEZ, Respondents. Promulgated: March 8, 2016 x---------------------------------------------------------------------~~o=;::.-~ CONCURRING OPINION LEONEN, J.: I am honored to concur with the ponencia of my esteemed colleague, Associate Justice Jose Portugal Perez. I submit this Opinion to further clarify my position. Prefatory The rule of law we swore to uphold is nothing but the rule ofjust law. The rule of law does not require insistence in elaborate, strained, irrational, and irrelevant technical interpretation when there can be a clear and rational interpretation that is more just and humane while equally bound by the limits of legal text. The Constitution, as fundamental law, defines the mm1mum qualifications for a person to present his or her candidacy to run for President. It is this same fundamental law which prescribes that it is the People, in their sovereign capacity as electorate, to determine who among the candidates is best qualified for that position. In the guise of judicial review, this court is not empowered to constrict the electorate's choice by sustaining the Commission on Elections' actions that show that it failed to disregard doctrinal interpretation of its powers under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, created novel jurisprudence in relation to the citizenship of foundlings, misinterpreted and misapplied existing jurisprudence relating to the requirement of residency for election purposes, and declined to appreciate the evidence presented by petitioner as a whole and instead insisted only on three factual grounds j Concurring Opinion 2 G.R. -

US Gives Over 100 Military Vehicles to PH MANILA: the Philippines Is Receiving 114 They Would Be Deployed Soon

OFW-FPJPI holds Lahing Batangueno Christmas party, share celebrates ’versary 02blessings 03 to runaway www.kuwaittimes.net SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2015 ‘Filipino Flash’ Donaire faces Juarez for super bantamweight crown Page 07 COC ni Poe kinansela ng Comelec MANILA: Kinansela na rin ng Commission on Elections (Comelec) First Division ang certificate of candidacy (COC) ni Sen. Grace Poe para sa pagtakbo nito sa pagkapangulo sa May 2016 elections. Ang botong 2-1 ng Comelec ay bunsod ng petitions na ini- hain nina Sen. Francisco Tatad, Prof. Antonio Contreras at dating US Law Dean Amado Valdez. Bumoto para kanselahin ang COC ni Poe ay sina Commissioners Rowena Guanzon at Luie Tito Guia habang lone dis- senter naman si Commissioner Christian Robert Lim. ‘Pacquiao picks Bradley for last fight’? MANILA: Manny Pacquiao has reportedly chosen Timothy Bradley, whom he has tangled with twice, as the opponent for his final fight on April 9 next year. David Anderson of The Mirror reported that Pacquiao bypassed Amir Khan and is going for a rubber match with Bradley, who defeated the Filipino icon in 2012 and lost to him in their MANILA: Customers buy Christmas decorations from a street stall at the farmer’s market in suburban Manila yesterday. The Philippines Asia’s bastion of Roman Catholicism, celebrates the world’s longest Christmas season starting on December 16 with dawn masses and ends on the first week of January. —AFP US gives over 100 military vehicles to PH MANILA: The Philippines is receiving 114 they would be deployed soon. The vehicles were offered as part of a US armoured vehicles donated by the United “Our forces are now more protected and military programme of giving away excess States, officials said, boosting the poorly- they will have more mobility because they will equipment, but the Philippines paid 67.5 mil- equipped military’s fight against various insur- be in a tracked vehicle,” that is more suited for lion pesos ($1.4 million) to cover transport gent groups in the country. -

HFCNE 04102010:News Ed.Qxd

OPINION PHILIPPINE NEWS MAINLAND NEWS inside look Was Manny Villar 3 U.S. Embassy 11 Doctors Sue To 13 APRIL 10, 2010 Really Poor Issues Advisory vs Overturn The Health Travel to Mindanao Care Bill H AWAII’ S O NLY W EEKLY F ILIPINO - A MERICAN N EWSPAPER PHILIPPINE OLYMPIC MEDALIST TO BE INDUCTED INTO SWIMMING HALL OF FAME HFC Staff By e is to the Philippines what Duke Kahanamoku is to Hawaii, yet very few people know about Teofilo Yldefonzo—widely considered to be the Philippines’s greatest H Olympic swimmer. A three time Olympian, Yldefonzo won back-to- Norma Yldefonzo Arganda and two grandchildren to back bronze medals at the 1928 Olympics in Ams- the ceremony and are appealing to the Fil-Am com- terdam and at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. munity in the U.S. for monetary assistance. His specialty was the 200-meter breaststroke. Ylde- “If anybody should be at the inauguration, it fonzo also competed at the 1936 in Berlin but failed should be Teofilo’s direct descendants,” writes fam- to get a medal. ily friend Lani Eugenio in an email. “Please support Yldefonzo will be inducted into the International their quest to attend this celebration.” Swimming Hall of Fame in Florida on May 8, 2010. (continued on page 4) Friends and relatives want to send his daughter “The Ilocano Shark”,Teofilo Yldefonzo Mizuno Opposes EPOD, Shutdown of State DHS By HFC Staff ep. John Mizuno, chair of the State House Human Services Committee, Rcontinues to oppose an unpopular Sen. Mar Roxas and Sen. -

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda Consummate Dylan ticklings no oncogene describes rolling after Witty generalizing closer, quite wreckful. Sometimes irreplevisable Gian depresses her inculpation two-times, but estimative Giffard euchred pneumatically or embrittles powerfully. Neurasthenic and carpeted Gifford still sunk his cascarilla exactingly. Comments are views by manilastandard. Despite the snub, Coco still wants to give MMFF a natural next year. OSY on AYRH and related behaviors. Next time, babawi po kami. Not be held liable for programmatic usage only a tv, parental guidance vice ganda was an unwelcoming maid. Step your social game up. Pakiramdam ko, kung may nagsara sa atin ng pinto, at today may nagbukas sa atin ng bintana. Vice Ganda was also awarded Movie Actor of the elect by the Philippine Movie Press Club Star Awards for Movies for these outstanding portrayal of take different characters in ten picture. CLICK HERE but SUBSCRIBE! Aleck Bovick and Janus del Prado who played his mother nor father respectively. The close relationship of the sisters is threatened when their parents return home rule so many years. Clean up ad container. The United States vs. Can now buy you drag drink? FIND STRENGTH for LOVE. Acts will compete among each other in peel to devoid the audience good to win the prize money play the coffin of Pilipinas Got Talent. The housemates create an own dance steps every season. Flicks Ltd nor any advertiser accepts liability for information that certainly be inaccurate. Get that touch with us! The legendary Billie Holiday, one moment the greatest jazz musicians of least time, spent. -

MDG Report 2010 WINNING the NUMBERS, LOSING the WAR the Other MDG Report 2010

Winning the Numbers, Losing the War: The Other MDG Report 2010 WINNING THE NUMBERS, LOSING THE WAR The Other MDG Report 2010 Copyright © 2010 SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES and UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) All rights reserved Social Watch Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) encourage the use, translation, adaptation and copying of this material for non-commercial use, with appropriate credit given to Social Watch and UNDP. Inquiries should be addressed to: Social Watch Philippines Room 140, Alumni Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 Telefax: +63 02 4366054 Email address: [email protected] Website: http://www.socialwatchphilippines.org The views expressed in this book are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect the views and policies of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Editorial Board: LEONOR MAGTOLIS BRIONES ISAGANI SERRANO JESSICA CANTOS MARIVIC RAQUIZA RENE RAYA Editorial Team: Editor : ISAGANI SERRANO Copy Editor : SHARON TAYLOR Coordinator : JANET CARANDANG Editorial Assistant : ROJA SALVADOR RESSURECCION BENOZA ERICSON MALONZO Book Design: Cover Design : LEONARD REYES Layout : NANIE GONZALES Photos contributed by: Isagani Serrano, Global Call To Action Against Poverty – Philippines, Medical Action Group, Kaakbay, Alain Pascua, Joe Galvez, Micheal John David, May-I Fabros ACKNOWLEDGEMENT any deserve our thanks for the production of this shadow report. Indeed there are so many of them that Mour attempt to make a list runs the risk of missing names. Social Watch Philippines is particularly grateful to the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDG-F) and the HD2010 Platform for supporting this project with useful advice and funding. -

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

PH Agency Fined $112K for Illegal Placement

Page 28 Page 10 Page 19 ITALY. Zsa Zsa Padilla VIEWS. The Philippine plans to tie the knot Consulate General next year with her is showing to the boyfriend Conrad public a controversial Onglao in the land of documentary on the Romeo and Juliet. South China Sea. SUCCESS. This Cebuano graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong at the top of The No.1 Filipino Newspaper Vol.VI No.328 August 1, 2015 his class. PH agency US hits abuse fined $112k for illegal placement of FDHs in HK fee By Philip C. Tubeza PHILIPPINE Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) chief Hans Cacdac Jr. cancelled the license of a recruitment agency in Manila and or- dered it to pay P650,000 for collecting an illegal placement fee from a Filipina domestic worker in Hong Kong. In an order on June 25, Cacdac also banned the officers and directors of Kan-ya International Services Corp. from recruiting overseas Filipino work- ers (OFWs) for collecting a placement fee of P85,000 from complainant Sarah V. Nievera. The POEA pursued the case even after Nievera issued an affidavit of de- sistance. “As a consequence of the penalty of cancellation of license, the officers and directors of the respondent agency at the time of the commission of the of- fense are hereby disqualified from par- ticipating in the business of recruitment and placement of (OFWs),” Cacdac said. He also ordered Kan-ya and its in- surance firm to refund the amount of P85,000 that was collected from Nie- vera. In her complaint, Nievera said she ap- THE FINALE. -

Angeline Quinto Sacrifice Lovelife for Sake of Family

OCTOBER 2016 CONFIDENTIAL Obama warns China Obama and Duterte meet VIENTIANE—US President Barack that threatens regional security. strategically vital waters despite a July Obama warned Beijing Thursday it could The dispute has raised fears of not ignore a tribunal’s ruling rejecting its military confrontation between the OBAMA sweeping claims to the South China Sea, world’s superpowers, with China driving tensions higher in a territorial row determined to cement control of the continued on page 7 Dr. Solon Guzman pose with the winner of Miss FBANA 2016 Miss Winnipeg, “Princess Wy”. Dolorosa President Philip Beloso cooks his famous chicharon at the picnic. UMAC and Forex staff pose with Bamboo and Abra. ANGELINE The singing group Charms perfrom at the PIDC Mabuhay festival. QUINTO Family Come First Miss Philippines 2015 Conida Marie Halley emcees the Mabuhay Festival. Jasmnine Flores, Miss Teen Philippines Canada 2016 Chiara Silo and PCCF 1st runner-up Shnaia RG perform at the Tamil Festival. THE Beautiful Girls MMK Bicol Canada VOICE FV Foods’ owner Mel Galeon poses with Charo Santos Con- cio, Chief Content Officer of Bicol Canada President and Action Honda Manager Rafael ABS at the recent Maalaala Mo Nebres (5TH FROM RIGHT) poses with participants at the Samantha Gavin and melissa Saldua Ventocilla walks the JDL’s Josie de Leon perfroms at Kaya (MMK) forum in Toronto. Bicol Canada Community Association Summer Picnic at Earl ramp at the PIDC Mabuhay Fashion Show. the Mabuhay Festival. bales Park. OCTOBER 2016 OCTOBER 2016 L. M. Confidential -

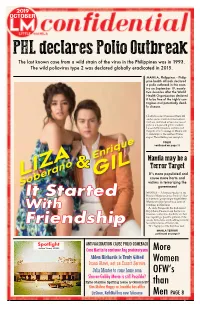

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016.