ZARIN TASNIM Student Id: 10108028

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectures on Development Strategy, Growth, Equity and the Political Process in Southern Asia

Lectures in DeLvelopment Economics No. 5 Lectures on Development Strategy, Growth, Equity and the Political Process in Southern Asia with c,,mments by Syed Nawab Haider Naqvi PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS ISLAMABAD Editor: Syed Nawab Haider Naqvi Co-Editor: Sarfraz K.Qureshi LiteraryEditor: S. H. H. Naqavi Biographical Sketch DR GUSTAV F. PAPANEK is currently on the faculty of Boston University, USA, where he has been Professor of Economics since 1974 and, concitrrently, Director of the Center for Asian Development Studies since 1983. Born on July 12, 1926, Professor Papanek had his higher education at Cornell University (B.Sc. in Agricultural Economi--. 1947) and Harvard University (M.A. in Economics in 1949 and Ph.D. in Economics in 1951). A prolific writer, Professor Papanek has authored, co-authored and edited several books and a very large number of articles, notes, comments, and contributions tu others' books. lis main interest lies in the areas of income distribut on, poverty, development strategy, industrial development, wages, and political economy. First published in Pakistan in 1986 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, storud in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form )r by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopy ing, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author a.-i the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. © Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. 1986 / ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Much of the underlying research for this study was supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) under coaitract No. AID OTR-G-1872. Eshya Mujahid's work on agriculture in the Punjabs and Bengals was supported by the Ford Foundation and Harendra Dey's work on labour income determination was supported by the International Labour Organization (ILO). -

Send Us Victorious N Zeeshan Khan World

MONDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2013 | www.dhakatribune.com Victory Day 2013 Illustration: Sabyasachi Mistry Send us victorious n Zeeshan Khan world. The economic exploitation was our surprise when our language, our When Babur, the Mughal, encoun- Charjapadas. It ran through the Pala acute, resulting in death by the mil- culture, our ethnicity, our economy tered this kingdom for the first time, and Sena kingdoms of Gaur-Bongo to or the generations born lions, but the strains on our social and and then ultimately our votes were in the 1500s he made this observation: the Vangaladesa of the Cholas and was after December 16, 1971, psychological well-being were equally subordinated to a national pecking reborn in the Sultanate of Bangala that Bangladesh was an exis- catastrophic. Added to that, a British order that placed us at the bottom. A “There is an amazing custom in Babur encountered. tentially “normal” place policy of advancing some communi- rude awakening followed, and then Bengal: rule is seldom achieved by The emergence of Bangladesh was to grow up in. Nothing in ties at the expense of others created the guns came out. hereditary succession. Instead, there a historical inevitability. Repeatedly, Fthe atmosphere hinted at the violent sectarian tensions that wouldn’t go Truth is, the break from Pakistan, is a specific royal throne, and each the people of this land have resist- upheavals our preceding generations away when 1947 rolled around. even from India earlier, was the of the amirs, viziers or office holders ed authority that was oppressive or had to contend with and there was But an independent Bengal was in has an established place. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement: Activism Across Borders for Palestinian Justice Suzanne Morrison A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 75,359 words. 2 Abstract On 7 July 2005, a global call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) was declared to people around the world to enact boycott initiatives and pressure their respective governments to sanction Israel until it complies with international law and respects universal principles of human rights. The call was endorsed by over 170 Palestinian associations, trade unions, non-governmental organizations, charities, and other Palestinian groups. The call mentioned how broad BDS campaigns were utilized in the South African struggle against apartheid, and how these efforts served as an inspiration to those seeking justice for Palestinians. -

Secret Detentions and Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh WATCH

H U M A N R I G H T S “We Don’t Have Him” Secret Detentions and Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh WATCH “We Don’t Have Him” Secret Detentions and Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34921 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34921 “We Don’t Have Him” Secret Detentions and Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh Map of Bangladesh ............................................................................................................. I Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Lack of Accountability .............................................................................................................. -

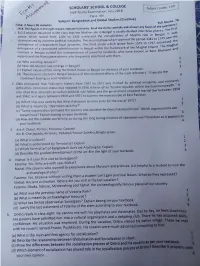

BGS-Assignement

Bangladesh and Global Studies Class: VIII Time: 50 Minutes Full Marks-50 1. Why the European Traders came to Bengal? a) for trade and commerce b) for importing manpower c) for exporting manpower d) for investment 2. When did the battle of Palassey take place? a) 1755 b) 1756 c) 1757 d) 1758 3. The characteristics of colonial rule are -------. i. don’t exercise their power permanently ii. One day they will go back iii. Send huge amount of money to their own country Which one of the following is correct? a) i and ii b) i and iii c) ii and iii d) i,ii and i 4. When does the colonial rule start in Bangla? a) 1757 b) 1758 c) 1759 d) 1760 5. Who was Bakhtiar Khiljee? a) A British Military ruler b) A Mughal Military ruler c) A Turkish Military ruler d) An Afgan Military ruler 6. Who established Independent Sultanate in Bengal? a) Issa Khan b) Sher Shah c) Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah d) Alaudddin Hossain Shah 7. The Independent Sultanate in Bengal lasted for………. a) 200 years b) 300 years c) 400 years d) 500 years 8. When did the powerful trade revolution start in Europe? a. 12th century b. 13th century c. 14th century d. 15th century 9. Who was Vasco-de-Gama? a) British Sailor b) Portuguese Sailor c) Dutch Sailor d) Indian Sailor 10. When the West Fallier accord was signed? a) 1645 b) 1646 c) 1647 d) 1648 11. 16. Who defeated Baro Bhuiyans and occupied Dhaka? a) Mir Jumla b) Bolbon c) Islam Khan d) Lord Clive 12. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science The

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement: Activism Across Borders for Palestinian Justice Suzanne Morrison A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 75,359 words. 2 Abstract On 7 July 2005, a global call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) was declared to people around the world to enact boycott initiatives and pressure their respective governments to sanction Israel until it complies with international law and respects universal principles of human rights. The call was endorsed by over 170 Palestinian associations, trade unions, non-governmental organizations, charities, and other Palestinian groups. The call mentioned how broad BDS campaigns were utilized in the South African struggle against apartheid, and how these efforts served as an inspiration to those seeking justice for Palestinians. -

The Status of Poor Women in Rural Bangladesh: Survival Through Socio-Political Conflict

The Status of Poor Women in Rural Bangladesh: Survival Through Socio-political Conflict By Fahria Enam Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax Nova Scotia August 2011 © Copyright by Fahria Eman, 2011 DALHOUSIE UNIVERISTY DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES The undersigned hereby certify that they have examined, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled ―The Status of Poor Women in Rural Bangladesh: Survival Through Socio-political Conflict‖ by Fahria Enam in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Dated: August 12, 2011 Supervisor: Examiners: ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: August 12, 2011 AUTHOR: Fahria Enam TITLE: The Status of Poor Women in Rural Bangladesh: Survival Through Socio- political Conflict DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Department of International Development Studies DEGREE: MA CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2011 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author‘s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the thesis (other than the brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgement in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. _______________________________ Fahria Enam iii Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................... -

Bangladesh: Human Rights Report 2015

BANGLADESH: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2015 Odhikar Report 1 Contents Odhikar Report .................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 4 Detailed Report ............................................................................................................................... 12 A. Political Situation ....................................................................................................................... 13 On average, 16 persons were killed in political violence every month .......................................... 13 Examples of political violence ..................................................................................................... 14 B. Elections ..................................................................................................................................... 17 City Corporation Elections 2015 .................................................................................................. 17 By-election in Dohar Upazila ....................................................................................................... 18 Municipality Elections 2015 ........................................................................................................ 18 Pre-election violence .................................................................................................................. -

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Bengali: ; 17 শখ মুিজবুর রহমান Bangabandhu March 1920 – 15 August 1975), shortened as Sheikh Mujib or just Mujib, was a Bangladeshi politician and statesman. He is called the ববু "Father of the Nation" in Bangladesh. He served as the first Sheikh Mujibur Rahman President of Bangladesh and later as the Prime Minister of শখ মুিজবুর রহমান Bangladesh from 17 April 1971 until his assassination on 15 August 1975.[1] He is considered to be the driving force behind the independence of Bangladesh. He is popularly dubbed with the title of "Bangabandhu" (Bôngobondhu "Friend of Bengal") by the people of Bangladesh. He became a leading figure in and eventually the leader of the Awami League, founded in 1949 as an East Pakistan–based political party in Pakistan. Mujib is credited as an important figure in efforts to gain political autonomy for East Pakistan and later as the central figure behind the Bangladesh Liberation Movement and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Thus, he is regarded "Jatir Janak" or "Jatir Pita" (Jatir Jônok or Jatir Pita, both meaning "Father of the Nation") of Bangladesh. His daughter Sheikh Hasina is the current leader of the Awami League and also the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. An initial advocate of democracy and socialism, Mujib rose to the ranks of the Awami League and East Pakistani politics as a charismatic and forceful orator. He became popular for his opposition to the ethnic and institutional discrimination of Bengalis 1st President of Bangladesh in Pakistan, who comprised the majority of the state's population. -

Genocide in the Liberation War of Bangladesh: a Case Study on Charkowa Genocide

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5766 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0484 (Online) Vol.11, No.6, 2021 Genocide in the Liberation War of Bangladesh: A Case Study on Charkowa Genocide Mohammad Abdul Baten Chowdhury Assistant Professor, Department of History & Civilization, University of Barishal, Barishal-8254, Bangladesh Md. Al-Amin* Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Barishal, Barishal-8254, Bangladesh Abstract The liberation war and the genocide of Bangladesh in 1971 are becoming the core research interest among genocide researchers, but the genocide in Charkowa has hardly been explored. As because of this, the current paper intended to explore the true history of the Charkowa genocide, where it found that on 20 August 1971 the Pakistani Army attacked the innocent people of Charkowa village and killed 16 people at the bank of Maragangi canal along with arson and looting of their homes and shops. The strategy was very obvious that it was a politicide type of genocide, where they wanted to destroy the support base of Mukti Bahini and the freedom fighters as well. Keywords: Genocide, Liberation War and Charkowa DOI: 10.7176/RHSS/11-6-02 Publication date: March 31 st 2021 1. Introduction Genocide in the 20th century became a common and so systematic and carried out most brutal activity “beginning with the deportation of Armenians from Ottoman territory, which may have taken the lives of as many as 1.8 million people in 1915. Nazi Germany engaged in mass extermination on a scale never seen before,”(Horvitz, Leslie Alan and Catherwood, 2006, p. -

Awami Leagueleague 1949-20161949-2016

journeyjourney ofof bangladesh awamiawami leagueleague 1949-20161949-2016 Bangladesh Awami League is the oldest and largest political party of Bangladesh. With the founding and operating principles of democra- cy, nationalism, socialism and secularism, the party has become synonymous with progress, prosperity, development and social justice. This publication gives a brief account of the illustrious history of the party which has become synonymous with that of the country. Formation - 1949 It was 1949. The wounds of the partition of the Indian Sub-Continent just two years back were still fresh. After the creation of Pakistan, it became im- mediately apparent that the discriminatory politics of the dominant West Pakistan could not live up to the aspirations of the majority Bangali people living in East Pakistan. Disenfranchised, a progressive seg- ment of the Muslim League decided to form their own party. 1949 1949 A Party is Born N 23RD JUNE, the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League was formed at a meeting chaired by Ataur Rahman Khan. The meeting, held at Dhaka’s K M Das Lane at the resi- dence of KM Bashir Humayun named ‘Rose Garden’, elected Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani as the President and49 Shamsul Hoque as the General Secretary of the Party. Historic Rose Garden, Dhaka 1950s Language Movement and United Front’s 21 Point N 26TH JANUARY, 1952 the then Governor-General Khwaja Nazimuddin announced that Urdu will be the only state language. While being treated at the Dhaka Medical’s prison ward, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman communicated with the party leaders and work- ers and gave directions for waging the language movement. -

Civil Society Joint Alternative Report on Bangladesh Submitted to the Committee Against Torture

Civil Society Joint Alternative Report on Bangladesh Submitted to the Committee against Torture 67th CAT session (22 July – 9August 2019) Joint submission by: Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC); Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD); Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM- ASIA); FIDH - International Federation for Human Rights; Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights; Odhikar; World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) Page 1 of 34 Table of Content 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 3 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................... 4 3. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON THE PROHIBITION OF TORTURE ............................... 5 4. CULTURE OF IMPUNITY .............................................................................................. 8 5. TORTURE AND ABUSE BY THE RAPID ACTION BATTALION ........................... 11 6. ARBITRARY DETENTION AND HARRASSMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS AND DISSIDENTS ........................................................................................ 13 7. TORTURE AND ILL-TRETMENT IN POLICE DETENTION AND AT ARREST ... 17 8. CONDITIONS OF DETENTION ................................................................................... 22 9. GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE ..................................................................................... 24 10. EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLING AND ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCE ......................