Conducive and Hindering Factors for Effective Disaster Risk Reduction In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highlights Situation Overview

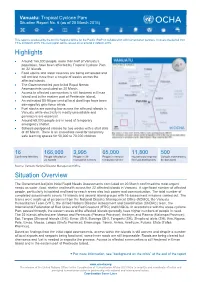

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 18 (as of 15 April 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners and in close support of the Government of Vanuatu. It covers the period from 8 to 15 April 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 22 April 2015. Highlights • The second round of distributions has commenced, with the first round now completed in Tanna Island but still under way in some areas of Pentecost and Maewo. • The Government-led assessment results have raised a number of concerns; two thirds of surveyed communities had severe WASH needs requiring immediate attention. • Better communication with the affected communities has been a significant gap in the response. • Coinciding with the recent rains in Port Vila, an increasing number of individuals have been approaching the NDMO and requesting tarpaulins. • This time of the year is the peak transmission season for vector-borne diseases. Partners are distributing bed nets across the country. • Around 140 government workers and partners responding to the cyclone aftermath in Tanna Island now have access to high-speed internet. 188,000 110,000 60,000 47,000 19,500 30,000 People affected People in need of School-age children People received Children vaccinated in Tanna Island across the country clean drinking water affected WASH supplies against measles reached with food Source: Government of Vanuatu’s National Disaster Management Office supported by the Vanuatu Humanitarian Team Situation Overview The first round of food distributions is now complete on Tanna Island, where it reached 30,000 people, and is expected to be finalised in the few remaining areas by the end of the week. -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Vanuatu: Dengue Fever Outbreak

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Vanuatu: Dengue fever outbreak DREF Operation n° MDRVU003 Glide n° EP-2017-000006-VUT Date issued: 27 January 2017 Date of disaster: 17 January 2017 Manager responsible for this DREF operation: Point of contact: Stephanie Zoll, disaster risk management coordinator, Jacqueline de Gaillande, CEO, IFRC country cluster support team (CCST) Suva Vanuatu Red Cross Society Operation start date: 26 January 2017 Operation end date: 26 April 2017 DREF operation budget: CHF 80,910 Expected timeframe: three (3) months Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 20,000 at risk 6,250 directly; 20,000 indirectly Host National Society presence (number of volunteers, staff, and branches): One headquarters office, six branches, 200 volunteers, 55 staff members. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: The Vanuatu Red Cross Society is coordinating, together with Movement partners, prevention and fumigation actions within the various projects being implemented in the country Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry of Health, Shefa Health Office, municipal mayors' offices, Vanuatu Police Force and the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) A. Situation Analysis Description of the disaster In November 2016, the Ministry of Health (MOH) has observed an increased reported cases of dengue infection in the country. Like other Pacific Island countries and territories, Vanuatu is prone to dengue outbreaks and epidemics. The country has experienced five major outbreaks since 1970 – the worst occurred in 1989 with over 3,000 admissions and 12 deaths. Since the 1989 outbreak, the government has upgraded its surveillance and control system and developed dengue preparedness plans. -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of CERF Funds

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the use of CERF funds RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS VANUATU RAPID RESPONSE CYCLONE 2015 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Ms. Osnat Lubrani REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. An AAR was organized and chaired by OCHA on behalf of the Resident Coordinator (RC) through the Pacific Humanitarian Team (PHT) on 19 January 2016. The lessons learning exercise was attended by PHT members, recipients of CERF funding and others. Representation was from UNICEF, WHO, FAO, UNFPA, IOM, WFP, the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office, UNDSS and OCHA. Similarly, the Government of Vanuatu convened a two-day workshop on lessons learnt from response to TC Pam on 24 and 25 June 2015 in Port Villa, Vanuatu. This was also attended by UN agencies, the International Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) Movement, I/NGOs and donors. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total -

Shefa Province Skills Plan 2015 - 2018

SHEFA PROVINCE SKILLS PLAN 2015 - 2018 Skills for Economic Growth CONTENTS Abbreviations 2 Forward by the Shefa Secretary General 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Vanuatu Training Landscape 6 3 Purpose 8 4 Shefa Province 9 5 Agriculture and Horticulture Sectors 12 6 Forestry Sector 18 7 Livestock Sector 21 8 Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector 25 9 Tourism and Hospitality Sector 28 10 Construction and Property Services Sector 32 11 Transport and Logistics Sector 37 12 Cross Sector 40 Appendix 1: Employability and Generic Skills 46 Appendix 2: Acknowledgments 49 ABBREVIATIONS BDS Business Development Services FAD Fish Aggregating Device FMA Fisheries Management Act GESI Gender Equity and Social Inclusion MoALFFBS Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries and Bio-Security MoET Ministry of Education and Training NGO Non-Government Organisations PSET Post School Education and Training PTB Provincial Training Boards TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training VAC Vanuatu Agriculture College VCCI Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry VESSP Vanuatu Education Sector Strategic Plan VIT Vanuatu Institute of Technology VQA Vanuatu Qualifi cations Authority FORWARD BY THE SHEFA SECRETARY GENERAL - MR MICHEL KALWORAI It is with much pleasure that I present to you our fi rst Skills Plan for Shefa Province; it specifi cally captures our training and learning development projections for four years, commencing this year 2015 and concluding in 2018. It also draws from, and refl ects, the Shefa Province Corporate Plan. It will be skill development that will assist us in improving and developing new infrastructure that will benefi t all in the province. It will drive the efforts of industry sectors seeking to achieve their commercial potential, in particular our agriculture and tourism sectors, both of which are seeking to improve productivity by having a skilled and qualifi ed workforce. -

VANUATU the Impact of Cyclone Pam

VANUATU The impact of Cyclone Pam Cyclone Pam – considered the worst natural disaster in the history of Vanuatu and the deadliest in the South Pacific since 2012 – made landfall on the 13th of March of 2015. The islands of Erromango, Tanna and Shepherd Islands which were directly on the path of the cyclone were among the most affected. Food Security Cluster Cyclone Pam impact maps & analysis Purpose of the assessment Purpose of the assessment The current report describes the impact of Acknowledgement Cyclone Pam throughout Vanuatu. Specifically, it reports on the cyclone’s impact WFP thanks the following for making and path to recovery in the areas of: available time and rapid field assessment reports on which this analysis is based: 1) Agriculture and livelihoods 2) Food needs NDMO 3) Housing UNDAC 4) Markets Women’s business and community 5) Health representatives of Port Vila. Peace Corps The report is designed to serve as a tool to Butterfly trust enable stakeholder/expert discussion and OCHA derive a common understanding on the ADF current situation. Food Security Cluster Samaritan’s Purse The report was compiled by: Siemon Hollema, Darryl Miller and Amy Chong (WFP) 1 Penama Cyclone Pam impact Sanma Cyclone Pam is the most powerful cyclone to ever hit the Southern Pacific. It formed near the Solomon Islands on the 6 March 2015 and traversed through Malampa several other island nations, including Solomon Islands, Kiribati and Tuvalu. On 13 March 2015, it strengthened to a Category 5 storm over the y-shaped chain of islands which make up Vanuatu. Vanuatu took multiple direct hits over 13 Mar 2015 the islands of Efate (where the capital Port Vila is 270km/h winds sustained situated), Erromango and Tanna Island. -

Léopold2016 Evaluating Harvest and Management Strategies for Sea

Evaluating harvest and management strategies for sea cucumber fisheries in Vanuatu Executive report August 2016 Marc Léopold BICH2MER Project No 4860A1 BICHLAMAR 4 Project No CS14-3007-101 Evaluating harvest and management strategies for sea cucumber fisheries in Vanuatu Marc Léopold August 2016 BICH2MER Project No 4860A1 BICHLAMAR 4 Project No CS14-3007-101 Harvest and management strategies in Vanuatu – Executive report – M. Léopold 2016 / 2 This executive report was produced specifically for consideration by the Department of Fisheries of the Government of Vanuatu following the closure of sea cucumber fisheries on December, 31 st 2015. It contains key findings and advice based the author’s research activities in Vanuatu between 2010 and 2016, relevant scientific literature, most recent catch and export monitoring records and interviews with managers of the Department of Fisheries of Vanuatu, community members, and members of the industry in Vanuatu conducted by the authors in March 2016. FUNDING The project was funded by the Government of New Caledonia, the Northern Province of New Caledonia and the IRD as part of the Memorandum of Understanding No 4860A1 (BICH2MER project) and as part of the contract No CS14-3007-101 between the Department of Fisheries of Vanuatu and the Government of New Caledonia (BICHLAMAR 4 project). ACKNOWLEGMENTS The author would like to thank the fishers, entitlement holders, processors, and managers of the Department of Fisheries of Vanuatu who contributed in a spirit of achieving the best outcomes for the sea cucumber fishery in Vanuatu. Particular thanks to Rocky Kaku and Jayven Ham of the Department of Fisheries of Vanuatu for organizing meetings and providing fishery data. -

Official Journal of the European Union C 391/1

Official Journal C 391 of the European Union Volume 58 English edition Information and Notices 24 November 2015 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES The 29th session took place in Suva (Fiji) from 15 to 17 June 2015. 2015/C 391/01 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific group of states, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of monday, 15 june 2015 . 1 2015/C 391/02 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the Members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of Tuesday, 16 June 2015 . 6 2015/C 391/03 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of Wednesday, 17 June 2015 . 11 EN KEYS TO SYMBOLS USED * Consultation procedure *** Consent procedure ***I Ordinary legislative procedure: first reading ***II Ordinary legislative procedure: second reading ***III Ordinary legislative procedure: third reading (The type of procedure is determined by the legal basis proposed in the draft act.) ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AFET Committee on Foreign Affairs DEVE Committee on -

Traditional Marine Resource Management in Vanuatu: Acknowledging, Supporting and Strengthening Indigenous Management Systems Francis R

SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin #20 – December 2006 11 Traditional marine resource management in Vanuatu: Acknowledging, supporting and strengthening indigenous management systems Francis R. Hickey1 Abstract Much of the marine related traditional knowledge held by fishers in Vanuatu relates to increasing catches while managing resources of cultural, social and subsistence value. Traditional beliefs and practices asso- ciated with fisheries and their management follow natural cycles of resource abundance, accessibility, and respect for customary rules enshrined in oral traditions. Many management related rules that control fish- ers’ behaviours are associated with the fabrication and deployment of traditional fishing gear. A number of traditional beliefs, including totemic affiliations and the temporal separation of agricultural and fishing practices, serve to manage marine resources. Spatial-temporal refugia and areas of symbolic significance create extensive networks of protected freshwater, terrestrial and marine areas. The arrival of Europeans initiated a process of erosion and transformation of traditional cosmologies and practices related to marine resource management. More recently, the forces of development and globali- sation have emerged to continue this process. The trend from a primarily culturally motivated regime of marine resource management to a more commercially motivated system is apparent, with the implemen- tation and sanctioning of taboos becoming increasingly less reliant on traditional beliefs and practices. This paper reviews a number of traditional marine resource management beliefs and practices formerly found in Vanuatu, many of which remain extant today, and documents the transformation of these systems in adapting to contemporary circumstances. By documenting and promoting traditional management sys- tems and their merits, it is hoped to advocate for a greater recognition, strengthening and support for these indigenous systems in Vanuatu and the region. -

OCHA VUT Tcpam Sitrep6 20

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 6 (as of 20 March 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 19 to 20 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 21 March 2015. Highlights Around 166,000 people, more than half of Vanuatu’s population, have been affected by Tropical Cyclone Pam on 22 islands. Food stocks and water reserves are being exhausted and will not last more than a couple of weeks across the affected islands. The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March. Access to affected communities is still hindered in Emae Island and in the eastern part of Pentecote Island. An estimated 50-90 per cent of local dwellings have been damaged by gale-force winds. Fuel stocks are running low across the affected islands in Vanuatu while electricity is mostly unavailable and generators are essential. Around 65,000 people are in need of temporary emergency shelter. Schools postponed classes for two weeks with a start date of 30 March. There is an immediate need for temporary safe learning spaces for 50,000 to 70,000 children. 16 166,000 3,995 65,000 11,800 500 Confirmed fatalities People affected on People in 39 People in need of Households targeted Schools estimated to 22 islands evacuation centres temporary shelter for food distributions be damaged Source: Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office Situation Overview The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March confirmed the most urgent needs as water, food, shelter and health across the 22 affected islands in Vanuatu. -

Vanuatu National Energy Road Map 2013-2020

Vanuatu National Energy Road Map 2013-2020 _________________________________________ March 2013 Acronyms and Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank AusAID Australian Agency for International Development CIF Climate Investment Funds DOE Department of Energy FAESP Framework for Action on Energy Security in the Pacific GHG Greenhouse Gas GoV Government of Vanuatu GPOBA Global Partnership for Output Based Aid HDI Human Development Index LED Light Emitting Diode LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas LV Low Voltage MEPS Minimum Energy Performance Standards MDGs Millennium Development Goals MIPU Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities MV Medium Voltage OBA Output Based Aid PALS Pacific Appliance Labeling and Standards PIES Public Institutions Electrification Scheme PPAs Power Purchase Agreements PPC Pacific Petroleum Company PPPs Public Private Partnerships PV Photovoltaic RLSS Rural Lighting Subsidy Scheme SREP Scaling Up Renewable Energy Program in Low Income Countries SWAp Sector Wide Approach SWER Single Wire Earth Return UNELCO Union Electrique du Vanuatu Limited URA Utilities Regulatory Authority VERD Vanuatu Energy for Rural Development VISIP Vanuatu Infrastructure Strategic Investment Plan VUI Vanuatu Utilities & Infrastructure Limited Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ iv Vanuatu National Energy Road Map ...................................................................................................... -

Kastom and Conservation: a Case Study of the Nguna-Pele Marine

KASTOM AND CONSERVATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE NGUNA-PELE MARINE PROTECTED AREA NETWORK by DANYEL ADDES (Under the Direction of Peter Brosius) ABSTRACT In Vanuatu, the Melanesian archipelago formally known as New Hebrides, traditional marine tenure has become a center piece of marine conservation efforts. However, its influence is relatively slight in the area of the Nguna-Pele Marine Protected Area Network (NPMPA), a village-based conservation organization. The NPMPA has therefore adopted a westernized conservation model of Marine Protected Areas, or MPAs. As it pursues its conservation goals, the NPMPA must continually negotiate between the expectations, tools, and methodologies, of two powerful normative discourses: traditional knowledge and national indigenous identity, and marine biology and conservation ecology. This case study uses discourse analysis to investigate the interactions of western conservation discourse and traditional forms of knowledge surrounding the management of marine resources. Findings suggest that the adaptation of western conservation practice has resulted in conservation discourse that situates agency in documents and conservation tools more often than in human action. INDEX WORDS: Ecological and Environmental Knowledge, Traditional Knowledge, Marine Conservation, Melanesia, Discourse Analysis KASTOM AND CONSERVATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE NGUNA-PELE MARINE PROTECTED AREA NETWORK by DANYEL ADDES B.A., University of Massachusetts, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in -

Justice Poor

JUSTICEfor the RESEARCH REPORT POOR SEPTEMBER 2010 Promoting equity and managing conflict in development Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Significant land loss was a unifying factor and mobilizing force behind Vanuatu’s independence movement, a key demand of which was the return of WAN LIS, FULAP STORI alienated land to custom landholders. The continuing alienation and use of land in Vanuatu remains an important source of conflict. Leasing plays a central role in contemporary alienation of customary land and is a common source of complaint. The formal legal framework for leasing fails to take into account LEASING ON EPI ISLAND, VANUATU Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized many of the local particularities of land holding and a lack of proper advice about the regulatory framework contributes to inequitable outcomes for landholders. In partnership with the Government and landholders, J4P explores these issues through in-depth research which provides evidence of the continuing uncertainty about land leasing and benefit distribution and its implications for group decision making. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Justice for the Poor is a World Bank research and development program aimed at informing, designing WAN LIS, FULAP STORI and supporting pro-poor approaches to justice reform. LEASING ON EPI ISLAND, VANUATU Public Disclosure Authorized RAEWYNPublic Disclosure Authorized PORTER AND ROD NIXON www.worldbank.org/justiceforthepoor WanLis_Cover_Sep16.indd 1 9/20/2010 3:07:41 PM Justice for the Poor is a World Bank research and development program aimed at informing, designing and supporting pro-poor approaches to justice reform. It is an approach to justice reform which sees justice from the perspective of the poor and marginalized, is grounded in social and cultural contexts, recognizes the importance of demand in building equitable justice systems, and understands justice as a cross-sectoral issue.