Factorization of Polynomials Given by Arithmetic Branching Programs∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NP-Hardness of Deciding Convexity of Quartic Polynomials and Related Problems

NP-hardness of Deciding Convexity of Quartic Polynomials and Related Problems Amir Ali Ahmadi, Alex Olshevsky, Pablo A. Parrilo, and John N. Tsitsiklis ∗y Abstract We show that unless P=NP, there exists no polynomial time (or even pseudo-polynomial time) algorithm that can decide whether a multivariate polynomial of degree four (or higher even degree) is globally convex. This solves a problem that has been open since 1992 when N. Z. Shor asked for the complexity of deciding convexity for quartic polynomials. We also prove that deciding strict convexity, strong convexity, quasiconvexity, and pseudoconvexity of polynomials of even degree four or higher is strongly NP-hard. By contrast, we show that quasiconvexity and pseudoconvexity of odd degree polynomials can be decided in polynomial time. 1 Introduction The role of convexity in modern day mathematical programming has proven to be remarkably fundamental, to the point that tractability of an optimization problem is nowadays assessed, more often than not, by whether or not the problem benefits from some sort of underlying convexity. In the famous words of Rockafellar [39]: \In fact the great watershed in optimization isn't between linearity and nonlinearity, but convexity and nonconvexity." But how easy is it to distinguish between convexity and nonconvexity? Can we decide in an efficient manner if a given optimization problem is convex? A class of optimization problems that allow for a rigorous study of this question from a com- putational complexity viewpoint is the class of polynomial optimization problems. These are op- timization problems where the objective is given by a polynomial function and the feasible set is described by polynomial inequalities. -

Exponents and Polynomials Exponent Is Defined to Be One Divided by the Nonzero Number to N 2 a Means the Product of N Factors, Each of Which Is a (I.E

how Mr. Breitsprecher’s Edition March 9, 2005 Web: www.clubtnt.org/my_algebra Examples: Quotient of a Monomial by a Easy does it! Let's look at how • (35x³ )/(7x) = 5x² to divide polynomials by starting Monomial • (16x² y² )/(8xy² ) = 2x with the simplest case, dividing a To divide a monomial by a monomial by a monomial. This is monomial, divide numerical Remember: Any nonzero number really just an application of the coefficient by numerical coefficient. divided by itself is one (y²/y² = 1), Quotient Rule that was covered Divide powers of same variable and any nonzero number to the zero when we reviewed exponents. using the Quotient Rule of power is defined to be one (Zero Next, we'll look at dividing a Exponent Rule). Exponents – when dividing polynomial by a monomial. Lastly, exponentials with the same base we we will see how the same concepts • 42x/(7x³ ) = 6/x² subtract the exponent on the are used to divide a polynomial by a denominator from the exponent on Remember: The fraction x/x³ polynomial. Are you ready? Let’s the numerator to obtain the exponent simplifies to 1/x². The Negative begin! on the answer. Exponent Rule says that any nonzero number to a negative Review: Exponents and Polynomials exponent is defined to be one divided by the nonzero number to n 2 a means the product of n factors, each of which is a (i.e. 3 = 3*3, or 9) the positive exponent obtained. We -2 Exponent Rules could write that answer as 6x . • Product Role: am*an=am+n Quotient of a Polynomial by a • Power Rule: (am)n=amn Monomial n n n • Power of a Product Rule: (ab) = a b To divide a polynomial by a n n n • Power of a Quotient Rule: (a/b) =a /b monomial, divide each of the terms • Quotient Rule: am/an=am-n of the polynomial by a monomial. -

Factoring and Roots

Factoring and roots Definition: A polynomial is a function of the form: n n−1 f(x) = anx + an−1x + ::: + a1x + a0 where an; an−1; : : : ; a1; a0 are real numbers and n is a nonnegative integer. The domain of a polynomial is the set of all real numbers. The degree of the polynomial is the largest power of x that appears. Division Algorithm for Polynomials: If p(x) and d(x) denote polynomial functions and if d(x) is a polynomial whose degree is greater than zero, then there are unique polynomial functions q(x) and r(x) such that p(x) r(x) d(x) = q(x) + d(x) or p(x) = q(x)d(x) + r(x). where r(x) is either the zero polynomial or a polynomial of degree less than that of d(x) In the equation above, p(x) is the dividend, d(x) is the divisor, q(x) is the quotient and r(x) is the remainder. We say d(x) divides p(x) () the remainder is 0 () p(x) = d(x)q(x) () d(x) is a factor of p(x). p(x) If d(x) is a factor of p(x), the other factor of p(x) is q(x), the quotient of d(x) . p(x) • Given d(x) , divide (using Long Division or Synthetic Division (if applicable)) to get the quotient q(x) and remainder r(x). Write the answer in division algorithm form: p(x) = d(x)q(x) + r(x). x3+1 • Write x−1 in division law form. -

Annotations of Kostant's Paper

ANNOTATIONS OF KOSTANT’S PAPER VIPUL NAIK Abstract. Here, I annotate Section 0 of Kostant’s paper on “Lie Group Representations on Polynomial Rings”. 1. The setup 1.1. Automorphisms of the polynomial ring. Let’s start with a commutative unital ring R and consider an R algebra S. Then an R automorphism of S is an automorphism of S that restricts to the identity map on R. The question I discuss here is: what is the structure of the R automorphism group of S when S is a free R algebra? That is, what is AutR(R[x1, x2, . xn])? To specify any endomorphism of S fixing R, we need to describe where each xi goes. Each xi goes to a polynomial pi(x1, x2 . xn). Every such choice of polynomials gives a unique endomorphism. Thus the structure of EndR(S) is simply the collection of all n tuples of polynomials with multiplication being composition. Note that EndR(S) is a noncommutative monoid. An linear endomorphism(defined) of R[x1, x2 . xn] is an automorphism that sends each xi to a linear combination of the xis. The composite of two linear maps corresponds to the composite of the n corresponding endomorphisms of R[x1, x2 . xn]. Thus, Mn(R) (the monoid of linear maps on R ) is a submonoid of EndR(R[x1, x2 . xn]). A linear automorphism(defined) is thus an invertible linear endomorphism. The corresponding linear map lies in GLn(R). Thus, GLn(R) is a subgroup of AutR(R[x1, x2 . xn]). What is so special about linear automorphisms? 1.2. -

Lesson 4-1 Polynomials

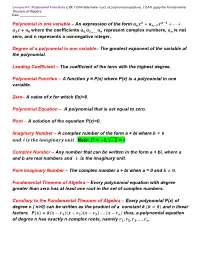

Lesson 4-1: Polynomial Functions L.O: I CAN determine roots of polynomial equations. I CAN apply the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra. Date: ________________ 풏 풏−ퟏ Polynomial in one variable – An expression of the form 풂풏풙 + 풂풏−ퟏ풙 + ⋯ + 풂ퟏ풙 + 풂ퟎ where the coefficients 풂ퟎ,풂ퟏ,…… 풂풏 represent complex numbers, 풂풏 is not zero, and n represents a nonnegative integer. Degree of a polynomial in one variable– The greatest exponent of the variable of the polynomial. Leading Coefficient – The coefficient of the term with the highest degree. Polynomial Function – A function y = P(x) where P(x) is a polynomial in one variable. Zero– A value of x for which f(x)=0. Polynomial Equation – A polynomial that is set equal to zero. Root – A solution of the equation P(x)=0. Imaginary Number – A complex number of the form a + bi where 풃 ≠ ퟎ 풂풏풅 풊 풊풔 풕풉풆 풊풎풂품풊풏풂풓풚 풖풏풊풕 . Note: 풊ퟐ = −ퟏ, √−ퟏ = 풊 Complex Number – Any number that can be written in the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers and 풊 is the imaginary unit. Pure imaginary Number – The complex number a + bi when a = 0 and 풃 ≠ ퟎ. Fundamental Theorem of Algebra – Every polynomial equation with degree greater than zero has at least one root in the set of complex numbers. Corollary to the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra – Every polynomial P(x) of degree n ( n>0) can be written as the product of a constant k (풌 ≠ ퟎ) and n linear factors. 푷(풙) = 풌(풙 − 풓ퟏ)(풙 − 풓ퟐ)(풙 − 풓ퟑ) … . -

Ideas of Newton-Okounkov Bodies

Snapshots of modern mathematics № 8/2015 from Oberwolfach Ideas of Newton-Okounkov bodies Valentina Kiritchenko • Evgeny Smirnov Vladlen Timorin In this snapshot, we will consider the problem of find- ing the number of solutions to a given system of poly- nomial equations. This question leads to the theory of Newton polytopes and Newton-Okounkov bodies of which we will give a basic notion. 1 Preparatory considerations: one equation The simplest system of polynomial equations we could consider is that of one polynomial equation in one variable: N N−1 P (x) = aN x + aN−1x + ... + a0 = 0 (1) Here a0, a1,. ., aN ∈ R are real numbers, and aN 6= 0 is (silently) assumed. The number N is the degree of the polynomial P . We might wonder: how many solutions does this equation have? We can extend (1) to a system of d equations which is of the form P1(x1, . , xd) = 0 P2(x1, . , xd) = 0 ... Pd(x1, . , xd) = 0, for some arbitrary positive integer d. Here, P1,P2,...,Pd are polynomials in d variables x1, x2, . , xd and the number of variables is always equal to the number of equations. In the following sections, we will extensively deal with the case d = 2. For the moment, though, let’s keep the case of one equation as in (1) and try to answer the question we posed before. 1 1.1 The number of solutions At first, consider the following example: Example 1. The equation xN − 1 = 0 has two real solutions, namely ±1, if N is even and one real solution, 1, if N is odd. -

Polynomial Functions of Higher Degree

Polynomial Functions of Higher Degree Polynomial Functions: Before we start looking at polynomials, we should know some common terminology. Definition: A polynomial of degree n is a function of the form nn−11 Px()= axnn++++ a−11 x... ax a0 where an ≠ 0 . The numbers aaa012, , , ... , an are called the coefficients of the polynomial. The number a0 is the constant coefficient or constant term. The number an , the coefficient of the highest power is the leading n coefficient, and the term axn is the leading term. Notice that a polynomial is usually written in descending powers of the variable, and the degree of a polynomial is the power of the leading term. For instance Px( ) = 45 x32−+ x is a polynomial of degree 3. Also, if a polynomial consists of just a single term, such as Qx()= 7 x4 , then it is called a monomial. Graphs of Polynomials: Polynomials of degree 0 are constant functions and polynomials of degree 1 are linear equations, whose graphs are both straight lines. Polynomials of degree 2 are quadratic equations, and their graphs are parabolas. As the degree of the polynomial increases beyond 2, the number of possible shapes the graph can be increases. However, the graph of a polynomial function is always a smooth continuous curve (no breaks, gaps, or sharp corners). Monomials of the form P(x) = xn are the simplest polynomials. By: Crystal Hull As the figure suggest, the graph of P(x) = xn has the same general shape as y = x2 when n is even, and the same general shape as y = x3 when n is odd. -

Degree of a Polynomial Ideal and Bézout Inequalities Daniel Lazard

Degree of a polynomial ideal and Bézout inequalities Daniel Lazard To cite this version: Daniel Lazard. Degree of a polynomial ideal and Bézout inequalities. 2020. hal-02897419 HAL Id: hal-02897419 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-02897419 Preprint submitted on 12 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Degree of a polynomial ideal and Bezout´ inequalities Daniel Lazard Sorbonne Universite,´ CNRS, LIP6, F-75005 Paris, France Abstract A complete theory of the degree of a polynomial ideal is presented, with a systematic use of the rational form of the Hilbert function in place of the (more commonly used) Hilbert polynomial. This is used for a simple algebraic proof of classical Bezout´ theorem, and for proving a ”strong Bezout´ inequality”, which has as corollaries all previously known Bezout´ inequal- ities, and is much sharper than all of them in the case of a non-equidimensional ideal. Key words: Degree of an algebraic variety, degree of a polynomial ideal, Bezout´ theorem, primary decomposition. 1 Introduction Bezout’s´ theorem states: if n polynomials in n variables have a finite number of common zeros, including those at infinity, then the number of these zeros, counted with their multiplicities, is the product of the degrees of the polynomials. -

Some Useful Functions - C Cnmikno PG - 1

Some useful functions - c CNMiKnO PG - 1 • Linear functions: The term linear function can refer to either of two different but related concepts: 1. The term linear function is often used to mean a first degree polynomial function of one variable. These functions are called ”linear” because they are precisely the functions whose graph in the Cartesian coordinate plane is a straight line. 2. In advanced mathematics, a linear function often means a function that is a linear map, that is, a map between two vector spaces that preserves vector addition and scalar multiplication. We will consider only first one of above meanings. Equations of lines: 1. y = ax + b - Slope-intercept equation 2. y − y1 = a(x − x1) - Point-slope equation 3. y = b - Horizontal line 4. x = c - Vertical line where x ∈ R, a, b, c ∈ R and a is the slope. −b If the slope a 6= 0, then x-intercept is equal . a • Quadratic function: f(x) = ax2 + bx + c for x ∈ R, where a, b, c ∈ R, a 6= 0. ∆ = b2 − 4ac This formula is called the discriminant of the quadratic equation. ! −b −∆ The graph of such a function is a parabola with vertex W , . 2a 4a A quadratic function is also referred to as: - a degree 2 polynomial, - a 2nd degree polynomial, because the highest exponent of x is 2. If the quadratic function is set equal to zero, then the result is a quadratic equation. The solutions to the equation are called the roots of the equation or the zeros of the function. -

Polynomial (Definition) a Monomial Or a Sum of Monomials

UNIT 6 POLYNOMIALS Polynomial (Definition) A monomial or a sum of monomials. A monomial is measured by its degree To find its degree, we add up the exponents of all the variables of the monomial. Ex. 2 x3 y4 z5 2 has a degree of 0 (do not mistake degree for zero exponent) x3 has an exponent of 3 y4 has an exponent of 4 z5 has an exponent of 5 Add up the exponents of your variables only 3 + 4 + 5 = 12 This monomial would be a 12th degree polynomial Let's Practice Finding the Degree of a Monomial 3 degree of ___ 3x degree of ___ 3x2 degree of ___ 3x3 degree of ___ 3x4 degree of ___ DEGREE OF A POLYNOMIAL The degree of a polynomial is determined by the monomial with the highest degree. 3 would be a 0 degree polynomial because all numbers have a degree of zero. (NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH ZERO EXPONENT PROPERTY). We call 0 degree polynomials CONSTANT. 3x would be a 1st degree polynomial because the 3 has a degree of 0 and x has an exponent of 1. We call 1st degree polynomials LINEAR. 3x2 would be a 2nd degree polynomial because the 3 has a degree of 0 and x2 has an exponent of 2. We call 2nd degree polynomials QUADRATIC. 3x3 would be a 3rd degree polynomial because the 3 has a degree of 0 and x3 has an exponent of 3. We call 3rd degree polynomials CUBIC. 3x4 would be a 4th degree polynomial because the 3 has a degree of 0 and x4 has an exponent of 4. -

Are Resultant Methods Numerically Unstable for Multidimensional Rootfinding?

Are resultant methods numerically unstable for multidimensional rootfinding? Noferini, Vanni and Townsend, Alex 2015 MIMS EPrint: 2015.51 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 ARE RESULTANT METHODS NUMERICALLY UNSTABLE FOR MULTIDIMENSIONAL ROOTFINDING? VANNI NOFERINI∗ AND ALEX TOWNSENDy Abstract. Hidden-variable resultant methods are a class of algorithms for solving multidimen- sional polynomial rootfinding problems. In two dimensions, when significant care is taken, they are competitive practical rootfinders. However, in higher dimensions they are known to miss zeros, cal- culate roots to low precision, and introduce spurious solutions. We show that the hidden-variable resultant method based on the Cayley (Dixon or B´ezout)resultant is inherently and spectacularly numerically unstable by a factor that grows exponentially with the dimension. We also show that the Sylvester resultant for solving bivariate polynomial systems can square the condition number of the problem. In other words, two popular hidden-variable resultant methods are numerically unstable, and this mathematically explains the difficulties that are frequently reported by practitioners. Along the way, we prove that the Cayley resultant is a generalization of Cramer's rule for solving linear systems and generalize Clenshaw's algorithm to an evaluation scheme for polynomials expressed in a degree-graded polynomial basis. Key words. resultants, rootfinding, conditioning, multivariate polynomials, Cayley, Sylvester AMS subject classifications. 13P15, 65H04, 65F35 1. Introduction. Hidden-variable resultant methods are a popular class of al- gorithms for global multidimensional rootfinding [1, 17, 27, 35, 39, 40]. -

A Polynomial of Degree N (In One Variable, with Real Coefficients) Is an Expression of the Form: Anxn + An-1Xn-1 + An-2Xn-2

A polynomial of degree n (in one variable, with real coefficients) is an expression of the form: n n−1 n−2 2 anx + an−1x + an−2x + ··· + a2x + a1x + a0 where an; an−1; an−2; ··· a2; a1; a0 are real numbers. Example: 3x4 − 2x2 + 1 is a polynomial of degree 4. −x10 + 7x5 − 2x3 + x − 5 is a polynomial of degree 10. −2x is a polynomial of degree 1. The constant expression 2 is a polynomial of degree 0. Notice that a linear expression is a polynomial of degree 1. The degree of a polynomial is the highest power of x whose coefficient is not 0. By convention, a polynomial is always written in decreasing powers of x. The coefficient of the highest power of x in a polynomial is the leading coeffi- cient. In the above example, the leading coefficient of p is 3. The leading coefficient of f is −1. The coefficient of a polynomial is understood to be 0 if the term is not shown. A polynomial of one term is a monomial. A polynomial of two terms is a binomial. A polynomial of three terms is a trinomial. A polynomial of degree 1 is a linear expression. A polynomial of degree 2 is a quadratic expression. A polynomial of degree 3 is a cubic expression. A polynomial of degree 4 is a quartic expression. A polynomial of degree 5 is a quintic expression. To add two polynomials, add their terms by collect like terms. E.g. (x3 + 2x2 − 3x + 4) + (−4x4 + 2x3 − 4x2 + x + 1) = −4x4 + 3x3 − 2x2 − 2x + 5 To subtract two polynomials, take the negatives of the second expression and add.