Cradle to Grave the Path of North Korean Innocents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Google Exec Gets Look at Nkoreans Using Internet 8 January 2013, by Jean H

Google exec gets look at NKoreans using Internet 8 January 2013, by Jean H. Lee trip include Schmidt's daughter, Sophie, and Jared Cohen, director of the Google Ideas think tank. Schmidt, who is the highest-profile U.S. business executive to visit North Korea since leader Kim Jong Un took power a year ago, has not spoken publicly about the reasons behind the journey to North Korea. Richardson has called the trip a "private, humanitarian" mission by U.S. citizens and has sought to allay worries in Washington. North Korea is holding a U.S. citizen accused by Pyongyang of committing "hostile" acts against the Executive Chairman of Google, Eric Schmidt, third from state, charges that could carry 10 years in a prison left, and former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson, or longer. Richardson told The Associated Press he second from right, watch as a North Korean student would speak to North Korean officials about surfs the Internet at a computer lab during a tour of Kim Kenneth Bae's detention and seek to visit the Il Sung University in Pyongyang, North Korea on American. Tuesday, Jan. 8, 2013. Schmidt is the highest-profile U.S. executive to visit North Korea - a country with Schmidt and Cohen chatted with students working notoriously restrictive online policies - since young leader Kim Jong Un took power a year ago. (AP on HP desktop computers at an "e-library" at the Photo/David Guttenfelder) university named after North Korea founder Kim Il Sung. One student showed Schmidt how he accesses reading materials from Cornell University online on a computer with a red tag denoting it as a Students at North Korea's premier university gift from Kim Jong Il. -

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

North Korea Today” Describing the Way the North Korean People Live As Accurately As Possible

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY http://www.goodfriends.or.kr/[email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.374 Priority Release November 2010 [“Good Friends” aims to help the North Korean people from a humanistic point of view and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as accurately as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Sound of Hailing at Farms at the News of No More Collection of Rice for Military Provision “Finally They Think of People” Meat Support Obligation to the Military Also Lifted “At least now we can fill our bellies with potatoes.” ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Every year when the harvest season approaches there were big conflicts at each regional farm between the military which tries to secure rice for military provision and farmers who refuse to hand over the rice they grew for the past one year. The conflicts are especially severe this year as the yields of harvest decrease because of the cold weather in the spring and the flood in the summer. In the case of North Hamgyong province it was reported that the level of discontent among farmers was serious enough to make the authorities worry. As the damage from flooding was so severe in the granary regions of North and South Hwanghae Provinces and North Pyongan Province it was decided that North Hamgyong Province was to provide rice for military provision first since it had better harvest. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

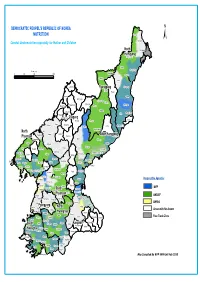

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies

81 Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing contemporary practices of unification on the peninsula. From the “small unification” (jageun tongil) where North Korean defectors pay brokers to bring family out, to the transmission of voice through the technology of mobile phones illegally smuggled from China, this paper explores practices of unification presently manifesting on the Korean Peninsula. National identity on both sides of the peninsula is usually linked with ethnic homogeneity, the ultimate idea of Koreanness present in both Koreas and throughout Korean history. Ethnic homogeneity is linked with nationalism, and while it is evoked as the rationale for unification it has not had that result, and did not prevent the ideological nationalism that divided the ethnos in the Korean War.1 The construction of ethnic homogeneity evokes the idea that all Koreans are one brethren (dongpo)—an image of one large, genetically related extended family. However, fissures in this ideal highlight the strength of genetic family ties.2 Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing “acts of unification” on the peninsula. -

Searchable PDF Format

- Yangdok Hot Spring Resort - Popular Ceramics Exhibition House - World of Prodigies Silver Ornament A gift presented to President Kim Il Sung by Kaleda Zia, Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh in April 1992 Monthly Journal (766) C O N T E N T S 3 Yangdok Hot Spring Resort 10 Korean Nation’s History of Using Hot Spring 11 Architecture for the People 12 Fruit of Enthusiasm 13 Offensive for Frontal Breakthrough and Increased Production and Economy 14 Old Home at Mangyongdae 17 The Secret Camp on Mt. Paektu 21 Understanding of the People Monthly journal Korea Today is posted on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 1 22 Seventy-fi ve Years of WPK (4) Revolutionary Martyrs Cemetery Tells 23 Relying on Domestic Resources 24 Consumer Changes to Producer 26 Popular Ceramics Exhibition House 28 Nano Cloth Developers Front Cover: Yangdok 29 Target of Developers Hot Spring Resort in the morning 30 World of Prodigies Photo by Kim Kum Sok 32 Record-breaking Achievement in 2019 36 True story I’ll Remain a Winner (7) 38 Promising Sheep Breeding Base 40 Pioneer of Complex Hand-foot Refl ex Therapy 41 Disabled Table Tennis Player 42 National Dog under Good Care 43 Story of Headmaster 44 Glimpse of Japan’s Plunder of Korean Cultural Heritage Back Cover: Moran Hill in spring 46 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (41) Photo by Kim Ji Ye Sijungho Mud Therapy 47 Poetess Ho Ran Sol Hon 13502 ㄱ – 208057 48 Mt Kuwol (3) Edited by Kim Myong Hak Address: Sochon-dong, Sosong District, Pyongyang, DPRK E-mail: fl [email protected] © The Foreign Language Magazines 2020 2 YYangdokangdok HHotot SSpringpring RResortesort No. -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

WATER SUPPLY and HABITAT PROJECTS in the DPRK ICRC Mission in the Democratic People’S Republic of Korea

PROJECT BRIEF WATER SUPPLY AND HABITAT PROJECTS IN THE DPRK ICRC Mission in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea PROGRAMME OVERVIEW Since 2013, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been working on water supply in peri-urban areas. Launched in different years, the four ongo- ing projects mainly involve construction with locally available materials and are in different phases of completion. Once finished, they will benefit about 123,750 inhabitants, ensuring they have sustainable access to clean water. Renovations at two local hospitals and two Physical Rehabilitation Centres will enable the public facilities to run more effectively and provide people with up-to-standard infra- structure and services. The Ministry of Urban Management PARTNERS The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Red Cross Society The International Committee of the Red Cross Water supply to peri-urban communities Jongpyong Eup Town water-supply system Kaechon City water-supply system Location Jongpyong, South Hamgyong Province Location Kaechon, South Pyongan Province Population targeted 43,000 Population targeted 59,200 Starting year 2018 Starting year 2019 Completion May 2020 Completion May 2020 Constructed in the 1970s, the existing water-supply system is Kaechon relies on a pumped water-supply system set up in unable to cover the current needs due to an increase in popu- the 1970s. Over the years, the quality of source well has wors- lation and reduction and deterioration of the water source. ened with the pumps too old to function fully, electricity for Households receive water in shifts and residents without piped pumping has been limited and distribution pipes are broken water in their houses draw it from hand-dug wells, which are and have developed leaks. -

Anecdotes of Kim Jong Il's Life 2

ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA JUCHE 104 (2015) At the construction site of the Samsu Power Station (March 3, 2006) At the Migok Cooperative Farm in Sariwon (December 3, 2006) At the Ryongsong Machine Complex (November 12, 2006) In a fish farm at Lake Jangyon (February 6, 2007) At the Kosan Fruit Farm (May 4, 2008) At the goat farm on the Phyongphung Tableland in Hamju County (August 7, 2008) With a newly-wed couple of discharged soldiers at the Wonsan Youth Power Station (January 5, 2009) At the Pobun Hermitage in Mt. Ryongak (January 17, 2009) At the Kumjingang Kuchang Youth Power Station (November 6, 2009) CONTENTS 1. AFFECTION AND TRUST .......................................................1 “Crying Faces Are Not Photogenic”........................................1 Laughter in an Amusement Park..............................................2 Choe Hyon’s Pistol ..................................................................3 Before Working Out the Budget ..............................................5 Turning “100m Beauty” into “Real Beauty”............................6 The Root Never to Be Forgotten..............................................7 Price of Honey .........................................................................9 Concrete Stanchions Removed .............................................. 10 -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE North Korean Literature: Margins of Writing Memory, Gender, and Sexuality A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Immanuel J Kim June 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Kelly Jeong, Chairperson Professor Annmaria Shimabuku Professor Perry Link Copyright by Immanuel J Kim 2012 The Dissertation of Immanuel J Kim is approved: _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the Korea Foundation for funding my field research to Korea from March 2010 to December 2010, and then granting me the Graduate Studies Fellowship for the academic year of 2011-2012. It would not be an overstatement for me to say that Korea Foundation has enabled me to begin and complete my dissertation. I would also like to thank Academy of Korean Studies for providing the funds to extend my stay in Korea. I am grateful for my advisors Professors Kelly Jeong, Henk Maier, and Annmaria Shimabuku, who have provided their invaluable comments and criticisms to improve and reshape my attitude and understanding of North Korean literature. I am indebted to Prof. Perry Link for encouraging me and helping me understand the similarities and differences found in the PRC and the DPRK. Prof. Kim Chae-yong has been my mentor in reading North Korean literature, opening up opportunities for me to conduct research in Korea and guiding me through each of the readings. Without him, my research could not have gotten to where it is today. Ch’oe Chin-i and the Imjingang Team have become an invaluable resource to my research of writers in the Writer’s Union and the dynamic changes occurring in North Korea today. -

Human Rights Without Frontiers International

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l: Willy Fautre By Willy Fautré Wednesday, 14 December 2011 Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Commemorating Human Rights Day 2011, Houses of Parliament London, 9 December 2011 Human rights in North Korea: An International Coalition To Stop Crimes Against Humanity Willy Fautré North Korea is ranked in every survey of freedom and human rights as the worst of the worst. An estimated 200,000 people are trapped in a brutal system of political prison camps akin to Hitler's concentration camps and Stalin's gulag. Slave labor, horrific torture and bestial living conditions are now well-documented in numerous reports by human rights organizations, through the testimonies of survivors of these camps who have escaped. Although there is still a shroud of mystery surrounding North Korea, the world can no longer claim ignorance as an excuse. Shocking accounts of the worst possible forms of torture have emerged from survivors of the gulags who have escaped. Lee Sung Ae told the British Parliament about how when she was jailed, all her finger-nails were pulled out, all her lower teeth destroyed, and prison guards poured water, mixed with chillies, up her nose. Jung Guang Il was subjected to "pigeon torture," with his hands cuffed and tied behind his back in an excruciating position. He said he felt as though his bones were breaking through his chest. All his teeth were broken during beatings and his weight fell from 75kg to 38kg. Kim Hye Sook spent 28 years in the gulag and was first jailed at the age of 13 because her grandfather had gone to South Korea.