Signature-Systems and Tonal Types in the Fourteenth-Century French Chanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRECENTO FRAGMENTS M Ichael Scott Cuthbert to the Department Of

T R E C E N T O F R A G M E N T S A N D P O L Y P H O N Y B E Y O N D T H E C O D E X a thesis presented by M ichael Scott Cuthbert t the Depart!ent " M#si$ in partia% "#%"i%%!ent " the re&#ire!ents " r the de'ree " D $t r " Phi% s phy in the s#b(e$t " M#si$ H ar)ard * ni)ersity Ca!brid'e+ Massa$h#setts A#'#st ,--. / ,--.+ Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert A%% ri'hts reser)ed0 Pr "0 Th !as F rrest 1 e%%y+ advisor Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert Tre$ent Fra'!ents and P %yph ny Bey nd the C de2 Abstract This thesis see3s t #nderstand h 4 !#si$ s #nded and "#n$ti ned in the 5ta%ian tre6 $ent based n an e2a!inati n " a%% the s#r)i)in' s #r$es+ rather than n%y the ! st $ !6 p%ete0 A !a( rity " s#r)i)in' s #r$es " 5ta%ian p %yph ni$ !#si$ "r ! the peri d 788-9 7:,- are "ra'!ents; ! st+ the re!nants " % st !an#s$ripts0 Despite their n#!eri$a% d !i6 nan$e+ !#si$ s$h %arship has )ie4 ed these s #r$es as se$ ndary <and "ten ne'%e$ted the! a%t 'ether= " $#sin' instead n the "e4 %ar'e+ retr spe$ti)e+ and pred !inant%y se$#%ar $ di6 $es 4 hi$h !ain%y ri'inated in the F% rentine rbit0 C nne$ti ns a! n' !an#s$ripts ha)e been in$ !p%ete%y e2p% red in the %iterat#re+ and the !issi n is a$#te 4 here re%ati nships a! n' "ra'!ents and a! n' ther s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns " p %yph ny are $ n$erned0 These s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns )ary in their $ nstr#$ti n and $ ntents>s !e are n t rea%%y "ra'!ents at a%%+ b#t sin'%e p %yph ni$ 4 r3s in %it#r'i$a% and ther !an#s$ripts0 5ndi)id#6 a%%y and thr #'h their )ery n#!bers+ they present a 4 ider )ie4 " 5ta%ian !#si$a% %i"e in the " #rteenth $ent#ry than $ #%d be 'ained "r ! e)en the ! st $are"#% s$r#tiny " the inta$t !an#s$ripts0 E2a!inin' the "ra'!ents e!b %dens #s t as3 &#esti ns ab #t musical style, popularity, scribal practice, and manuscript transmission: questions best answered through a study of many different sources rather than the intense scrutiny of a few large sources. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Music Perception in Historical Audiences: Towards Predictive Models of Music Perception in Historical Audiences

journal of interdisciplinary music studies 2014-2016, volume 8, issue 1&2, art. #16081204, pp. 91-120 open peer commentary article Music perception in historical audiences: Towards predictive models of music perception in historical audiences Marcus T. Pearce1 and Tuomas Eerola2 1Queen Mary University of London, London E1 4NS 2Durham University, Durham DH1 3RL Background in Historical Musicology. In addition to making inferences about historical performance practice, it is interesting to ask questions about the experience of historical listeners. In particular, how might their perception vary from that of present-day listeners (and listeners at other time points, more generally) as a function of the music to which they were exposed throughout their lives. Background in Music Cognition. To illustrate the approach, we focus on the cognitive process of expectation, which has long been of interest to musicians and music psychologists, partly because it is thought to be one of the processes supporting the induction of emotion by music. Recent work has established models of expectation based on probabilistic learning of statistical regularities in the music to which an individual is exposed. This raises the possibility of developing simulations of historical listeners by training models on the music to which they might have been exposed. Aims. First, we aim to develop a framework for creating and testing simulated perceptual models of historical listeners. Second, we aim to provide simple but concrete illustrations of how the simulations can be applied in a preliminary approach. These are intended as illustrative feasibility studies to provide a springboard for further discussion and development rather than fully fledged experiments in their own right. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Dir So, Trobar Vers, Entendre Razo. Poetry and Music in Medieval Romance Lyric*

Philomusica on-line 16 (2017) Dir so, trobar vers, entendre razo. Poetry and music in medieval Romance lyric* Maria Sofia Lannuti Università degli Studi di Pavia-Cremona [email protected] § Fino a che punto, nella lirica romanza § To what extent, in medieval del medioevo, l’idea di un’originaria Romance lyric, is the idea of an simbiosi tra parola e musica è original symbiosis between word and storicamente fondata? Prendendo in music historically grounded? Taking considerazione documenti e testi into account medieval documents letterari e non, il saggio intende and texts, both literary and non- sostenere l’ipotesi che un aspetto literary, this essay explores the fondamentale del rapporto tra poesia e interpretive hypothesis that one musica sia rimasto invariato dalle fundamental aspect of the relation- origini della lirica romanza fino alla fine ship between poetry and music del Trecento: l’indipendenza delle due remained unchanged from the forme d’arte nel processo creativo, e origins of Romance lyric through to conseguentemente il prevalere di una the end of the fourteenth century: the divisione delle competenze e dei ruoli independence of the two forms of art tra poeti e musicisti. in the creative process, and conse- quently the prevalence of a division of competence and role between poets and musicians. «Philomusica on-line» – Rivista del Dipartimento di Musicologia e beni culturali e-mail: [email protected] – Università degli Studi di Pavia <http://philomusica.unipv.it> – ISSN 1826-9001 – Copyright © 2017 by the Authors Philomusica on-line 16 (2017) Tacea la notte placida e bella in ciel sereno la luna il viso argenteo mostrava lieto e pieno.. -

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

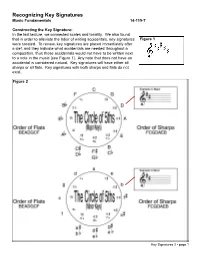

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

Bells and Trumpets, Jesters and Musici: Sounds and Musical Life in Milan Under the Visconti

Lorenzo Tunesi – Bells and Trumpets, Jesters and Musici 1 Bells and Trumpets, Jesters and Musici: Sounds and Musical life in Milan under the Visconti Or questa diciaria, Now [I conclude] my speech, perché l’Ave Maria since the Ave Maria sona, is ringing, serro la staciona I shut up shop nén più dico1 and I won’t talk anymore These verses, written by the Milanese poet and wealthy member of the ducal chancellery Bartolomeo Sachella, refer to a common daily sound in late Medieval Milan. The poet is quickly concluding his poem, since the Ave Maria is already sounding. When church-bells rang the Ave Maria, every citizen knew, indeed, that the working-day was over; thus, probably after the recitation of a brief prayer in honour of the Virgin, shops closed and workers went home. Church-bells were only one of the very large variety of sounds characterising Medieval cities. Going back over six-hundred years, we could have been surrounded by city-criers accompanied by trumpet blasts, people playing music or singing through the streets, beggars ringing their bells asking for charity, mothers’ and children’s voices, horses’ hoofs and many other sounds. All these sounds created what musicology has defined as ‘urban soundscape’, which, since the pioneering study by Reinhard Strohm, Music in Late Medieval Bruges (1985), has deeply intrigued music historians. The present essay aims to inquire into the different manifestations of musical phenomena in late Medieval Milan, relating them to the diverse social, cultural and historical contexts in which they used to take place. My research will focus on a time frame over a century, ca. -

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There are two general forms we will concern ourselves with: verse and prose. Verse is metered, prose is not. Poetry is a genre, or type (from the Latin genus, meaning kind or race; a category). Other genres include drama, fiction, biography, etc. POETRY. Poetry is described formally by its foot, line, and stanza. 1. Foot. Iambic, trochaic, dactylic, etc. 2. Line. Monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetramerter, Alexandrine, etc. 3. Stanza. Sonnet, ballad, elegy, sestet, couplet, etc. Each of these designations may give rise to a particular tradition; for example, the sonnet, which gives rise to famous sequences, such as those of Shakespeare. The following list is taken from entries in Lewis Turco, The New Book of Forms (Univ. Press of New England, 1986). Acrostic. First letters of first lines read vertically spell something. Alcaic. (Greek) acephalous iamb, followed by two trochees and two dactyls (x2), then acephalous iamb and four trochees (x1), then two dactyls and two trochees. Alexandrine. A line of iambic hexameter. Ballad. Any meter, any rhyme; stanza usually a4b3c4b3. Think Bob Dylan. Ballade. French. Line usually 8-10 syllables; stanza of 28 lines, divided into 3 octaves and 1 quatrain, called the envoy. The last line of each stanza is the refrain. Versions include Ballade supreme, chant royal, and huitaine. Bob and Wheel. English form. Stanza is a quintet; the fifth line is enjambed, and is continued by the first line of the next stanza, usually shorter, which rhymes with lines 3 and 5. Example is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. -

Acadian Music As a Cultural Symbol and Unifying Factor

L’Union Fait la Force: Acadian Music as a Cultural Symbol and Unifying Factor By Brooke Bisson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studies at Saint Mary's University Halifax, Nova Scotia A ugust 27, 2003 I Brooke Bisson Approved By: Dr. J(Jihn Rgid Co-Supervisor Dr. Barbara LeBlanc Co-Supervisor Dr. Ma%aret Harry Reader George'S Arsenault Reader National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1^1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisisitons et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-612-85658-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-612-85658-5 The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of theL'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither thedroit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from Niit la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou aturement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. In compliance with the Canadian Conformément à la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privée, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this dissertation. -

Middle Ages Declarative Knowledge

Middle Ages Declarative Knowledge Comparison between Middle Ages and Renaissance Middle Ages Renaissance Long, asymmetrical Shorter, balanced Melody Texted melodies often melismatic Texted melodies often syllabic Smoother, more regular Rhythm Restless and active Often tied to rhythm or words Based on triads Based on fifths and octaves Dissonance less harsh, usually on weak Harmony Unexpected, pungent beats dissonances More adventurous in late Renaissance in portraying emotions Often a cappella or purely Voices and instruments mixed instrumental Sound Bright colors, freely mixed Softer tone colors, ensembles of similar instruments (consorts) Monophonic and polyphonic Mostly polyphonic Texture Non-imitative Often imitative Often based on cantus firmus or Some isorhythm, but usually based on isorhythm text or dance forms Form Vocal refrain forms (virelay, Through-composed vocal pieces rondeau) (madrigal and motet) Sacred Music of the Middle Ages I. Liturgy: Set Structure of Christian Church Service 1. Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590–604) codified church music 2. Gregorian chant (plainchant, plainsong) 1. vocal monophony, nonmetric, sung in Latin, conjunct melody 2. over 3,000 melodies anonymously composed 3. text settings: syllabic, neumatic, melismatic 4. early chant: handed down through oral tradition 5. notated by neumes: square notes on four-line staff 6. modes: precede major and minor scales II. The Mass: Reenactment of the Sacrifice of Christ 1. Most solemn ritual of the Catholic church 1. Proper: variable portions 2. Ordinary: fixed portions 3. offices: not part of the Mass, worship in monasteries http://ibscrewed4music.blogspot.com/ III. A Gregorian Melody: Kyrie 1. Kyrie: first in the Ordinary 1. Greek prayer in three parts 2.