Antony and Cleopatra History Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

Shakespeare and the “Live” Theatre Broadcast Experience / Pascale Aebischer, Susanne Greenhalgh, and Laurie E

Early Modern Culture Volume 14 First-Generation Shakespeare Article 19 6-15-2019 Shakespeare and the “Live” Theatre Broadcast Experience / Pascale Aebischer, Susanne Greenhalgh, and Laurie E. Osborne Eric Brinkman Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc Recommended Citation Eric Brinkman (2019) "Shakespeare and the “Live” Theatre Broadcast Experience / Pascale Aebischer, Susanne Greenhalgh, and Laurie E. Osborne," Early Modern Culture: Vol. 14 , Article 19. Available at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc/vol14/iss1/19 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Modern Culture by an authorized editor of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pascale Aebischer, Susanne Greenhalgh, and Laurie E. Osborne, eds. Shakespeare and the “Live” Theatre Broadcast Experience. The Arden Shakespeare, 2018. 252 pp. Reviewed by ERIC BRINKMAN ascale Aebischer, Susanne Greenhalgh, and Laurie E. Osborne’s edited volume Shakespeare and the “Live” Theatre Broadcast Experience is an accessible P introduction to some of the concerns in the emergent field of live broadcast studies. Comprised of an introduction, fifteen generally brief chapters by various authors, an epilogue, and an appendix listing the digital theatre broadcasts of Shakespeare from 2003 to 2017, this volume covers a wide range of interests and concerns centered on how scholars can analyze and think about the meanings embedded in and produced by the broadcast -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Witness for the Prosecution by Agatha Christie

IMAGE RELEASE – 27 November 2019 Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | Website Eleanor Lloyd Productions and Rebecca Stafford Productions present Witness for the Prosecution By Agatha Christie • First look at the fifth cast of hit production Witness for the Prosecution now in its killer third year • The production welcomes new cast members including Taz Skylar as the accused Leonard Vole, Alexandra Guelff as Romaine Vole, Jo Stone-Fewings as Sir Wilfrid Robarts QC, Jeffery Kissoon as Mr Justice Wainwright and Crispin Redman as Mr Mayhew • Images can be downloaded HERE Taz Skylar as Leonard Vole and the cast of Witness for the Prosecution. Credit Ellie Kurttz Now in its third year, Witness for the Prosecution has today released a first glimpse at production images featuring its killer fifth cast, who had their first performance on 19 November 2019. Brand new production photography can be downloaded here. Set in the breathtaking Chamber space at London’s County Hall, director Lucy Bailey (Ghosts, Love From A Stranger) welcomes audiences to judge the Whodunnit classic for themselves, while seating them in “the comfiest seats in London” (New York Times). Agatha Christie’s gripping story of justice, passion and betrayal also allows audience members to join the Jury Box, casting their vote as the action unfolds before them. The new cast includes Taz Skylar (Warheads, Lie Low, The Kill Team) as the accused Leonard Vole, Alexandra Guelff (Gaslight, Ghosts, The Busy Body) in the role of Romaine Vole, Jo Stone-Fewings (Trust, Home I’m Darling, King John) as Sir Wilfrid Robarts QC, Kevin McMonagle (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, People, Places and Things, Bramwell) playing Mr Myers QC, Jeffery Kissoon (EastEnders, Grange Hill, Julius Caesar/ The Meeting/ Antony and Cleopatra) as Mr Justice Wainwright, Crispin Redman (Law & Order, Love From A Stranger, Yes, Prime Minister) as Mr Mayhew. -

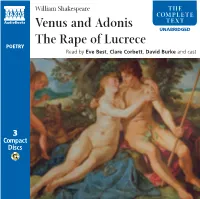

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo Da Vinci) Tom Has Been Seen in A

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo da Vinci) Tom has been seen in a variety of TV roles, recently portraying Dr. Laurence Shepherd opposite James Nesbitt and Sarah Parish in ITV1’s critically acclaimed six-part medical drama series “Monroe.” Tom has completed filming the highly anticipated second season which premiered autumn 2012. In 2010, Tom played the role of Gavin Sorensen in the ITV thriller “Bouquet of Barbed Wire,” and was also cast in the role of Mr. Wickham in the ITV four-part series “Lost in Austen,” alongside Hugh Bonneville and Gemma Arterton. Other television appearances include his roles in Agatha Christie’s “Poirot: Appointment with Death” as Raymond Boynton, as Philip Horton in “Inspector Lewis: And the Moonbeams Kiss the Sea” and as Dr. James Walton in an episode of the BBC series “Casualty 1906,” a role that he later reprised in “Casualty 1907.” Among his film credits, Tom played the leading roles of Freddie Butler in the Irish film Happy Ever Afters, and the role of Joe Clarke in Stephen Surjik’s British Comedy, I Want Candy. Tom has also been seen as Romeo in St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold alongside Colin Firth and Rupert Everett and as the lead role in Santiago Amigorena’s A Few Days in September. Tom’s significant theater experiences originate from numerous productions at the Royal Court Theatre, including “Paradise Regained,” “The Vertical Hour,” “Posh,” “Censorship,” “Victory,” “The Entertainer” and “The Woman Before.” Tom has also appeared on stage in the Donmar Warehouse theatre’s production of “A House Not Meant to Stand” and in the Riverside Studios’ 2010 production of “Hurts Given and Received” by Howard Barker, for which Tom received outstanding reviews and a nomination for best performance in the new Off West End Theatre Awards. -

P a T E N H U G H

cowboy + cougar productions P A T E N H U G H E S SAG-AFTRA — AEA hair: Blonde eyes: blue height: 5’7 DIGITAL SERIES HEIRLOOM (Vimeo) Series Regular Dir. Michael Melamedoff; Writer Bekah Brunstetter Co-Creator THEATRE Three Sisters Irina The Old Vic New Voices / Dir. Eve Best Halo/Titanic Paten The Old Vic / Dir. David Chapman Color the Sky! Daphne Palm Beach Theatre / Blythe Danner, Ed Herrmann Buskers Heidi Kole The Old Vic; SoHo House NY / Dir. Danny Mendoza The Thin Line One-Woman Show AddVerb Productions / Dir. Cathy Plourde Tits and Blood Portia Edinburgh Festival Fringe Animal (US/UK Exchange) Jo The Public Theater / Dir. Emmy Frank Shotz! various The Kraine Theatre / AMIOs Theatre Company Bound in a Nutshell Ophelia u.s. New York International Fringe / Dir. Greg Wolfe Mannequin’s Ball by Bruno Jasienski Mannequin Counterpoint Theatre / Dir. Allison Troupe-Jensen My Name is Rachel Corrie Rachel Dir. Jaq Bessell (Shakespeare’s Globe) Collected Scenes of Macbeth Macbeth R.A.D.A / Dir. Ché Walker Othello Desdemona W&L University / Dir. Joseph D. Martinez The Shape of Things Evelyn W&L University / Dir. Tom Ziegler The Long Christmas Ride Home Claire W&L University / Dir. Tom Ziegler FILM Long Nights Short Mornings Supporting The Orchard / Dir. Chadd Harbold Coach of the Year Supporting Dir. David Stott / with Ed Herrmann Beauty Mark Supporting Dir. Harris Doran / LAFF 2017 Charity (short) Lead Dir. Joe Quartaro Awake (short) Supporting Prod: Lee Cleary TRAINING The Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (R.A.D.A.), London, England, Shakespeare Program The T.S. -

Lesley Lamont-Fisher Make-Up & Hair Designer

Lesley Lamont-Fisher Make-Up & Hair Designer Credits include: THE ENGLISH Writer/Director: Hugo Blick Revenge Romantic Western Producer: Colin Wratten Featuring: Emily Blunt, Chaske Spencer, Rafe Spall Production Co: Drama Republic / BBC One / Amazon THAT GOOD NIGHT Director: Eric Styles Drama Producers: Alan Latham, Charles Savage Featuring: John Hurt, Sofia Helin, Charles Dance, Erin Richards Production Co: GSP Studios INDIAN SUMMERS Directors: John Alexander, Anand Tucker, David Moore Period Drama Series Producer: Dan Winch Featuring: Julie Walters, Henry Lloyd-Hughes, Jemima West Production Co: New Productions / Channel 4 LIFE IN SQUARES Director: Simon Kaijser Period Drama Producer: Rhonda Smith Featuring: James Norton, Eve Best, Phoebe Fox, Lydia Leonard Production Co: Ecosse Films / BBC Two BLACK MIRROR: Production Co: Zeppotron / Channel 4 Satirical Sci-Fi Thriller Dramas Producer: Barney Reisz WHITE CHRISTMAS Director: Carl Tibbets Featuring: John Hamm, Rafe Spall, Oona Chaplin BE RIGHT BACK Director: Owen Harris Featuring: Hayley Atwell, Domhnall Gleeson, Claire Keelan BAFTA Nomination for a Single Drama THE WALDO MOMENT Director: Bryn Higgins Featuring: Jason Flemyng, Tobias Menzies WHITE BEAR Director: Carl Tibbetts Featuring: Tuppence Middleton, Michael Smiley THE NATIONAL ANTHEM Director: Otto Bathurst Featuring: Lindsay Duncan, Rory Kinnear, Donald Sumpter Rose d’Or Festival Nomination for Best Comedy Broadcast Award Nomination for Best Single Drama FIFTEEN MILLION MERITS Director: Euros Lyn Featuring: Daniel Kaluuya, Jessica -

University of Birmingham from Global London to Global Shakespeare

University of Birmingham From global London to global Shakespeare Mancewicz, Aneta DOI: 10.1080/10486801.2017.1365716 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Mancewicz, A 2018, 'From global London to global Shakespeare', Contemporary Theatre Review, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10486801.2017.1365716 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 10/09/2018 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary Theatre Review on 11/06/18, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/10486801.2017.1365716 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -