Viewer Writes of How Outkast Raps About “Cadillacs Rather Than Benzes, Chicken Wings Rather Than Moet” (Qtd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bradley Syllabus for South

Special Topics in African American Literature: OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D. Course Description In 1995, Atlanta, GA, duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards, where they won the award for best new duo. Mostly attended by bicoastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the South got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American South after the civil rights movement. Using a variety of post–civil rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop South,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last twenty-five years. Course Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical listening journal • Nerdy hip hop review **Explicit Content Statement** (courtesy: Dr. Treva B. Lindsey) Over the course of the semester students will be introduced to texts that may be explicit in nature (i.e., cursing, sexual content). -

The Good Life Rich Nathan February 13 & 14, 2016 the Good Life John 10:1-10

The Good Life Rich Nathan February 13 & 14, 2016 The Good Life John 10:1-10 This week, our entire church, from preschoolers through adults, will begin to focus our attention for the next six weeks on The Good Life. What it is and how we can live it. All of my messages are followed up by a video teaching that all of our small groups will be watching in their small group meeting. We prayed to start up 350 new groups during this campaign. As of this weekend, 390 of you have signed up to host a group. I just want to say “thank you”! This is the very last weekend to sign up to host a group. Following the service, head out to the lobby at your campus to sign up to host a small group. Every attendee will receive a copy of the daily devotions that have been prepared for the six weeks of this Good Life series. We’ve already given out thousands of copies of the devotional. You don’t want to miss this, if you are not in small group, again head out to the lobby following the service to join a group or simply go online to vineyardcolumbus.org. Everyone will be talking about the Good Life. There’s a periodical out called The Vegan Good Life. Picture of the Magazine It’s advertised as being Packed with the very best in vegan fashion, travel, lifestyle, art and design So vegans have particular destinations for their travel. Would that include avoiding all roads that pass by dairy farms or ice cream stands? Making sure that the vehicle you’re traveling in has no leather seats? Vegan travel. -

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15 Written by Robert ID2755 Wednesday, 21 June 2006 00:11 - Rap artist Ali, of the platinum selling hip-hop group St. Lunatics, and "Dirty South" hip-hop impresario Goodie Mob alum rap artist Big Gipp will be releasing their hip-hop collaborative debut album, Kinfolk, August 15th. Kinfolk comes following up their appearance on the #1 hit track ‘Grillz’ with fellow hip-hop artist Nelly and will be on his record label, Derrty Ent., an imprint of Universal Motown Records. The first single off the album, “Go ‘Head,” is an anthemic summer song that combines "midwest swing" with southern crunk and is produced by up and coming St. Louis native Trife. "Gipp and I started hanging out a while back and found that we had a lot in common," says Ali. "We''re both considered leaders in our crews, we''re fathers and even though we have different styles, we respect each other's skills." Gipp describes their collaborative effort as “the best of both worlds-- the St. Lunatics kicked off the midwest movement and Goodie Mob helped establish southern rap, that’s why I say it’s the best of both worlds; Plain and simple." In that spirit, Kinfolk has a mix of songs featuring "St. Louis" hip-hop kin: rap artists Nelly, Murphy Lee and Derrty Ent newcomers, Chocolate Tai and Avery Storm; "Atlanta" hip-hop kin Cee-lo and other southern hip-hop all-stars include rappers Juvenile, David Banner, Three 6 Mafia and Bun B. The album collab also contains a mix of mid-west and southern producers including the St. -

Outkast Stankonia Album Download Outkast Stankonia Album Download

outkast stankonia album download Outkast stankonia album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67ab1adfff2e15e4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. OutKast – Stankonia (20th Anniversary Deluxe) (2000/2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] OutKast – Stankonia (20th Anniversary Deluxe) (2000/2020) FLAC (tracks) 24-bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 01:37:50 minutes | 1,11 GB | Genre: Hip- Hop, Rap Studio Master, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © LaFace – Legacy. OutKast is celebrating the 20th-anniversary of their seminal album Stankonia with a set of bonus tracks, previously unreleased remixes, streaming bundles and vinyl and digital editions. According to reports, the digital re-release will arrive in 24-bit and 360 Reality Audio formats, and will feature a total of six bonus tracks that include a remix of “B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad)” by Zack de la Rocha of Rage Against The Machine, a remix of “Ms. Jackson” by Mr. Drunk, a remix of “So Fresh, So Clean” with Snoop Dogg and Sleepy Brown, plus a cappella versions of the three songs. -

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: a Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’S “Mainstream” (1996)

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) MITCHELL OHRINER[1] University of Denver ABSTRACT: Recent years have seen the rise of musical corpus studies, primarily detailing harmonic tendencies of tonal music. This article extends this scholarship by addressing a new genre (rap music) and a new parameter of focus (rhythm). More specifically, I use corpus methods to investigate the relation between metric ambivalence in the instrumental parts of a rap track (i.e., the beat) and an emcee’s rap delivery (i.e., the flow). Unlike virtually every other rap track, the instrumental tracks of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) simultaneously afford hearing both a four-beat and a three-beat metric cycle. Because three-beat durations between rhymes, phrase endings, and reiterated rhythmic patterns are rare in rap music, an abundance of them within a verse of “Mainstream” suggests that an emcee highlights the three-beat cycle, especially if that emcee is not prone to such durations more generally. Through the construction of three corpora, one representative of the genre as a whole, and two that are artist specific, I show how the emcee T-Mo Goodie’s expressive practice highlights the rare three-beat affordances of the track. Submitted 2015 July 15; accepted 2015 December 15. KEYWORDS: corpus studies, rap music, flow, T-Mo Goodie, Outkast THIS article uses methods of corpus studies to address questions of creative practice in rap music, specifically how the material of the rapping voice—what emcees, hip-hop heads, and scholars call “the flow”—relates to the material of the previously recorded instrumental tracks collectively known as the beat. -

Ceelo Green – Primary Wave Music

CEELO GREEN facebook.com/ceelogreen twitter.com/CeeLoGreen instagram.com/ceelogreen/ open.spotify.com/artist/5nLYd9ST4Cnwy6NHaCxbj8 Thomas DeCarlo Callaway (born May 30, 1974), known professionally as CeeLo Green (or Cee Lo Green), is an American singer, songwriter, rapper, record producer and actor. Green came to initial prominence as a member of the Southern hip hop group Goodie Mob and later as part of the soul duo Gnarls Barkley, with record producer Danger Mouse. Internationally, Green is best known for his soul work: his most popular was Gnarls Barkley’s 2006 worldwide hit “Crazy”, which reached number 1 in various singles charts worldwide, including the UK. In the United States, “Crazy” reached number two on the Billboard Hot 100. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Goodie Mob Amazing Grays Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Big Rube Amazing Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Calm B 4 Da Storm Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Survival Kit Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Back2Back Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Try We Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Off-Road Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Big Rube's Road Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob 4 My Ppl Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Dc Young Fly Crowe's Nest Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Prey -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Goodie Mob Album Featuring Ceelo Drops on Groupon

August 23, 2013 Goodie Mob Album Featuring CeeLo Drops on Groupon First Goodie Mob Album in 14 Years For Sale Today on Groupon.com CHICAGO--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Groupon (NASDAQ: GRPN) (http://www.groupon.com) today announces a deal for Goodie Mob's first album in 14 years. Groupon has a limited supply of Goodie Mob's new album, "Age Against the Machine," which officially releases from Primary Wave on Aug. 27. The CD is now available for purchase at Groupon.com for $8.99 at http://gr.pn/180qCBQ. The first single off the new Goodie Mob album is entitled, "Special Education," featuring Janelle Monae. The album also features T.I., and Goodie Mob's U.S. tour kicks off this weekend on Aug. 24 in Washington, with a special stop the following night in Brooklyn, N.Y. for a post-VMAs concert at Brooklyn Bowl. Goodie Mob's last released single was "Fight To Win," in the summer of 2012, an anthem of liberation, motivation and determination to always fight to win in life, a motto that the Goodie Mob lives by. Also, CeeLo Green's memoire, "Everybody's Brother," releases Sept. 10. In addition to the new album, tour and book, CeeLo and Goodie Mob will be the subjects of a new reality series to debut in 2014. Goodie Mob is a pioneering Southern hip-hop group and one of the most celebrated rap acts to come out of the hip-hop hotbed of Atlanta. Formed in 1991, Goodie Mob's original and current group members include CeeLo Green, Big Gipp, Khujo and T-Mo, all of whom grew up together in Atlanta alongside the rest of the Dungeon Family—the musical collective of Southern rappers, which includes Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast, Organized Noise and Parental Advisory. -

February 18, 2002 TABLE of CONTENTS DUKE DAYS EVENTS CALENDAR

■ P*f* M PJ PU.17 PtVMMia Exilarlno artistic firms mm —I»pumn— From boy bands lo 'Oawson s A professional artist presents a collection George Mason University s defense sparks a 72- JMU students discuss thei including intricate m 'Burning King of Fire' 64 comeback win over ]MU in a crucial confer- toward today's pop culture. at the Mitten Gallery. ence game. James Madison University Today: Sunny rN(h:«a REEZE * Low: 22 THEVol. i '', /sM(C ><S Father dies Habitat after D-hall Black Panther Party myths dispelled heart attack Co-founder speaks on party origins; Malcolm X assassination struggles BY DAVID CI.EMENTSON Black Panther Party in 1966 The father of two students senior writer to raise died Thursday after suffering in Oakland, Calif. According a heart attack in D-hall. There are two things that to Jacqueline Walker, associ- William Tarrant III. 49, Bobby Scale, co-founder and ate professor of history, funds collapsed in D-hall around 7 former chairman of the Black many viewed the Black Panther Party, said he really Panthers as a violent, revolu- BY BRANDON HUC.III \K\ fin Thursday, according to contributing writer hates: myths and the assassi- tionary organization aimed Director of University This semester, the |MU Communications Fred nation of Malcolm X. at overthrowing the federal "1 don't care for myths government in an armed chapter of Habitat lor Hilton. People on the scene Humanity will help two and rescue squad paramedics and all that stuff," Seale told Marxist rebellion. 150 people in the 1SAT Health "They called me a hood- underpnvdeged local families administered CPR. -

Music to Your Teeth

Play-A-Grill: Music to Your Teeth Aisen Caro Chacin Design and Technology Department 6 E 16th St. Parsons The New School for Design New York, NY 10003 USA [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. ORIGIN This paper is an in depth exploration of the fashion object and 2.1 Experiments and Inspiration device, the Play-A-Grill. It details inspirations, socio-cultural This concept was inspired by an interactive installation at the implications, technical function and operation, and potential Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco called Sound Bite that applications for the Play-A-Grill system. displayed bone vibration hearing through a rod [8]. A user could Keywords slide a straw over a rod, and through biting it and closing her Digital Music Players, Hip Hop, Rap, Music Fashion, Grills, ears, could hear any four different types of music. The clearest Mouth Jewelry, Mouth Controllers, and Bone Conduction sound came from a hip hop music sample. This experience spun Hearing. an ongoing conversation in my mind about bone conduction and its applications. 1. INTRODUCTION 2.2 Hearing Through Teeth Play-A-Grill, (see Figure 1) combines a digital music player Bone conduction hearing has been used since the 1880’s in with the mouth piece jewelry known as a grill, which is usually commercial products to aid hearing loss, except in patients associated with hip hop and rap music genres. Grills are almost suffering from damage to their auditory nerves. Rhode’s always made of precious metal, most notably gold or platinum. Audiophone (see Figure 2), also known as the acoustic fan, was They are completely removable, and worn as a retainer. -

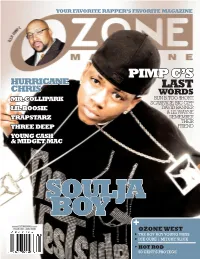

PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR

OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR. COLLIPARK BUN B, TOO $HORT, SCARFACE, BIG GIPP LIL BOOSIE DAVID BANNER & LIL WAYNE REMEMBER TRILL N*GGAS DON’T DIE DON’T N*GGAS TRILL TRAPSTARZ THEIR THREE DEEP FRIEND YOUNG CASH & MIDGET MAC SOULJA BOY +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS JANUARY 2008 ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S LAST WORDS SOULJA BUN B BOY TOO $HORT CRANKIN’ IT SCARFACE ALL THE WAY BIG GIPP TO THE BANK WITH DAVID BANNER MR. COLLIPARK LIL WAYNE FONSWORTH LIL BOOSIE’S BENTLEY JEWELRY CORY MO 8BALL & FASCINATION MORE TRAPSTARZ SHARE THEIR THREE DEEP FAVORITE MEMORIES OF THE YOUNG CASH SOUTH’S & MIDGET MAC FINEST HURRICANE CHRIS +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden features ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson 54-59 YEAR END AWARDS PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 76-79 REMEMBERING PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 22-23 RAPPERS’ NEW YEARS RESOLUTIONS LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 74 DIRTY THIRTY: PIMP C’S GREATEST HITS SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

Rosa Parks: Outkast

Rosa Parks: Outkast (Hook) Ah ha, hush that fuss Everybody move to the back of the bus Do you wanna bump and slump with us We the type of people make the club get crunk Verse 1:(Big Boi) Many a day has passed, the night has gone by But still I find the time to put that bump off in your eye Total chaos, for these playas, thought we was absent We takin another route to represent the Dungeon Family Like Great Day, me and my nigga decide to take the back way We stabbing every city then we headed to that bat cave A-T-L, Georgia, what we do for ya Bull doggin hoes like them Georgetown Hoyas Boy you sounding silly, thank my Brougham aint sittin pretty Doing doughnuts round you suckas like then circles around titties Damn we the committee gone burn it down But us gone bust you in the mouth with the chorus now (Hook) I met a gypsy and she hipped me to some life game To stimulate then activate the left and right brain Said baby boy you only funky as your last cut You focus on the past your ass'll be a has what Thats one to live by or either that one to die to I try to just throw it at you determine your own adventure Andre, got to her station here's my destination She got off the bus, the conversation lingered in my head for hours Took a shower kinda sour cause my favorite group ain't comin with it But I'm witcha you cause you probably goin through it anyway But anyhow when in doubt went on out and bought it Cause I thought it would be jammin but examine all the flawsky-wawsky Awfully, it's sad and it's costly, but that's all she wrote And I hope I never have to float in that boat Up shit creek it's weak is the last quote That I want to hear when I'm goin down when all's said and done And we got a new joe in town When the record player get to skippin and slowin down All yawl can say is them niggas earned that crown but until then..