Understanding Obesity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adipose Tissue As Pain Generator in the Lower Back and Lower Extremity

Lee et al. HCA Healthcare Journal of Medicine (2020) 1:5 https://doi.org/10.36518/2689-0216.1102 Clinical Review Adipose Tissue as Pain Generator in the Lower Back and Lower Extremity: Application in Author affiliations are listed Musculoskeletal Medicine at the end of this article. Se Won Lee, MD ,1 Craig Van Dien, MD ,2 Sun Jae Won, MD, PhD3 Correspondence to: Se Won Lee, MD Abstract Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Description MoutainView Medical Adipose tissue (AT) has diverse and important functions in body insulation, mechanical protection, energy metabolism and the endocrine system. Despite its relative abundance in Center the human body, the clinical significance of AT in musculoskeletal (MSK) medicine, partic- 2880 N Tenaya Way, 2nd Fl, ularly its role in painful MSK conditions, is under-recognized. Pain associated with AT can Las Vegas, NV 89128 be divided into intrinsic (AT as a primary pain generator), extrinsic (AT as a secondary pain ([email protected]) generator) or mixed origin. Understanding AT as an MSK pain generator, both by mechanism and its specific role in pain generation by body region, enhances the clinical decision-making process and guides therapeutic strategies in patients with AT-related MSK disorders. This article reviews the existing literature of AT in the context of pain generation in the lower back and lower extremity to increase clinician awareness and stimulate further investigation into AT in MSK medicine. Keywords adipose tissue; fat pad; musculoskeletal pain; connective tissue; lipodystrophy; lipoma; obe- sity; lipedema; pain generator Introduction lower extremity, focusing on its pathogenic role Mounting evidence supports the various func- as a pain generator as well as practical diagno- tions of adipose tissue (AT), most notably its sis and management. -

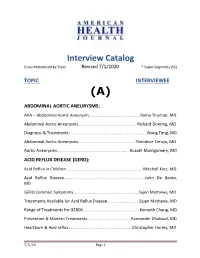

AHJ Interview Catalog 7-1-13(9)

Interview Catalog Cross Referenced by Topic Revised 7/1/2020 * Super Segments (SS) TOPIC INTERVIEWEE (A) ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSMS: AAA – Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm………………………………………….Rama Thumati, MD Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms………………………………………………..Richard Doering, MD Diagnosis & Treatments…………………………………………………………..…...Wang Teng, MD Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms……………………………………………...Theodore Teruya, MD Aortic Aneurysms...............................................................Russell Montgomery, MD ACID REFLUX DISEASE (GERD): Acid Reflux in Children...................................................................Mitchell Katz, MD Acid Reflux Disease……………………………………………………………….….John De Banto, MD GERD Common Symptoms……………………………………………………..Sajen Mathews, MD Treatments Available for Acid Reflux Disease............................Sajen Mathews, MD Range of Treatments for GERDS.................................................Kenneth Chang, MD Prevention & Modern Treatments......................................Parminder Dhaliwal, MD Heartburn & Acid reflux………...............................................Christopher Hurley, MD 7/1/20 Page 1 ACL TEAR (ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR) ACL Tear/Injuries‐Female Atheletes Prevention....................John A. Schlechter, DO ACNE: Acne……………………………………………………………………………….Sharon Christopher, PA‐C Best Methods of Treating Acne.……………………………………………Gene Rubinstein, MD Flaxel Repair Laser (Part 1)………………………………………………………Michael Persky, MD Flaxel Laser/Recovery & Results (Part 2)………………………………….Michael Persky, MD ACUPUNCTURE: -

July 14, 2019 the Honorable Jan

July 14, 2019 The Honorable Jan Schakowsky 2367 Rayburn HOB Washington, DC 20515 Dear Representative Schakowsky: On behalf of University of Pennsylvania Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, I’m writing to inform you that we would like to offer our formal endorsement of the Lymphedema Treatment Act (S.518/H.R.1948). I am a practicing cancer physiatrist at Penn Medicine and frequently evaluate, diagnose, and manage lymphedema. Many of my patients have lymphedema as a result of cancer treatment, while others have lymphedema as a result of congenital lymphedema, Milroy’s disease, Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, lipedema, organ transplantation, chronic venous insufficiency, or trauma. Despite the cause of lymphedema, the international standard of care for treatment includes lymphedema therapy and long term use of compression garments that at a minimum needs to be replaced every 6 months. Lymphedema is a life-long condition that requires ongoing medical management along with continuous compression. The current international standard of care for lymphedema requires use of appropriate compression on a 24-hour basis. Failure to provide adequate compression can lead to significant medical, psychological and functional morbidity. Specifically, patients are left vulnerable to worsening lymphedema, potentially life- threatening cellulitis infections, chronic pain and non-healing wounds. Unfortunately, Medicare currently does not cover these medically necessary compression garments, despite the evidence for the increase in morbidity and mortality associated with untreated lymphedema and the international standard of care to treat with 24-hour compression garments. Furthermore, many patients are unable to financially afford the costs of compression garments that can be several hundred dollars a year. -

Obesity Without Sleep Apnea Is Associated with Daytime Sleepiness

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Obesity Without Sleep Apnea Is Associated With Daytime Sleepiness Alexandros N. Vgontzas, MD; Edward O. Bixler, PhD; Tjiauw-Ling Tan, MD; Deborah Kantner, BS; Louis F. Martin, MD; Anthony Kales, MD Background: Daytime sleepiness and fatigue is a fre- onset of sleep, and total wake time were significantly quent complaint of obese patients even among those who lower, whereas the percentage of sleep time was signifi- do not demonstrate sleep apnea. cantly higher in obese patients compared with controls. In contrast, during the nighttime testing, obese patients Objective: To assess in the sleep laboratory whether obese compared with controls demonstrated significantly higher patients without sleep apnea are sleepier during the day wake time after onset of sleep, total wake time, and lower compared with healthy controls with normal weight. percentage of sleep time. An analysis of the relation be- tween nighttime and daytime sleep suggested that day- Methods: Our sample consisted of 73 obese patients time sleepiness in obese patients is a result of a circa- without sleep apnea, upper airway resistance syn- dian abnormality rather than just being secondary to drome, or hypoventilation syndrome who were consecu- nighttime sleep disturbance. tively referred for treatment of their obesity and 45 con- trols matched for age. All patients and healthy controls Conclusions: Daytime sleepiness is a morbid charac- were monitored in the sleep laboratory for 8 hours at night teristic of obese patients with a potentially significant im- and at 2 daytime naps, each for 1 hour the following day. pact on their lives and public safety. Daytime sleepiness in individuals with obesity appears to be related to a meta- Results: Obese patients compared with controls were bolic and/or circadian abnormality of the disorder. -

Surgical Treatments for Lymphedema and Lipedema BACKGROUND

Name of Blue Advantage Policy: Surgical Treatments for Lymphedema and Lipedema Policy #:719 Latest Review Date: September 2020 Category: Medical/Surgical Policy Grade: B BACKGROUND: Blue Advantage medical policy does not conflict with Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), Local Medical Review Policies (LMRPs) or National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) or with coverage provisions in Medicare manuals, instructions or operational policy letters. In order to be covered by Blue Advantage the service shall be reasonable and necessary under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, Section 1862(a)(1)(A). The service is considered reasonable and necessary if it is determined that the service is: 1. Safe and effective; 2. Not experimental or investigational*; 3. Appropriate, including duration and frequency that is considered appropriate for the service, in terms of whether it is: • Furnished in accordance with accepted standards of medical practice for the diagnosis or treatment of the patient’s condition or to improve the function of a malformed body member; • Furnished in a setting appropriate to the patient’s medical needs and condition; • Ordered and furnished by qualified personnel; • One that meets, but does not exceed, the patient’s medical need; and • At least as beneficial as an existing and available medically appropriate alternative. *Routine costs of qualifying clinical trial services with dates of service on or after September 19, 2000 which meet the requirements of the Clinical Trials NCD are considered reasonable and necessary by Medicare. Providers should bill Original Medicare for covered services that are related to clinical trials that meet Medicare requirements (Refer to Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Chapter 1, Section 310 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual Chapter 32, Sections 69.0-69.11). -

Lower Extremity Edema.Pdf

May 2019 ELDER CARE A Resource for Interprofessional Providers Lower Extremity Edema in Older Adults Oluwaseun O. Acquah, MD, Jennifer M. Vesely, MD, Teresa Quinn, MD, and Donald Pine, MD Family Medicine Residency, University of Minnesota Methodist Hospital Lower extremity edema is the accumulation of fluid in the Bilateral edema, which is more common in older adults, is lower legs, which may or may not include the feet (pedal often multifactorial and may reflect a systemic process. edema). It is typically caused by one of three mechanisms. Treating the underlying systemic cause can often lessen the edema. Table 1 lists common causes of bilateral lower The first is venous edema caused by increased capillary extremity edema. permeability, resulting in a fluid shift from the veins to the interstitial space. The fluid shift can be due to venous In addition to seeking evidence for these conditions, disease or systemic processes that cause the fluid shift. clinicians should be aware of certain clues in the patient’s presentation. In particular, if unilateral edema has an The second is lymphatic edema caused by obstruction or acute-onset (present for less than 72 hours), venous dysfunction of lymphatic outflow from the legs, resulting in thrombosis and infection should be considered as possible accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid. causes and steps should be taken to exclude those The third is from lipoedema, which is an accumulation of diagnoses. On the other hand, when edema is long- fluid in fat cells. These three mechanisms can operate standing and accompanied by a dull, aching pain, chronic independently or in combination. -

Sakakawea Dispatch

Winter 2018-2019 Sakakawea Medical Center Sakakawea Dispatch Inside this issue: This institution is an equal opportunity provider. CCCHC Providers 2 Construction 3 Update for CCCHC Darrold Bertsch, SMC CEO Receives Grassroots Champion Award Emergency 4 Department Each year, the American Hospital Association (AHA), in conjunction with the state hospital associations, recognizes the achievements of grassroots Triage 4 leaders with the prestigious Grassroots Champion Award. One hospital Charity Care 4 leader from each state is honored for his or her work over the previous year in effectively delivering the hospital message to elected officials; Lymphedema helping to broaden the base of community support for hospitals; and 5 Program advocating tirelessly on behalf of patients, hospitals and communities. Patient Satisfaction 5 The American Hospital Association in conjunction with the North Dakota Surveys State Hospital Association named Sakakawea Medical Center, CEO, Stop the Bleed 6 Darrold Bertsch as the 2018 Grassroots Champion. Bertsch earned this special recognition through his dedication to the hospital mission, on both Welcome the local and the national level. 7 Dr. Fogarty Mr. Bertsch was recognized during the during the AHA annual meeting and Tobacco Cessation 7 was presented with the award during the North Dakota Hospital Association annual conference that was held in Fargo, North Dakota. Visiting Specialists 8 Darrold Bertsch, CEO of Sakakawea Medical Center SMC and Jen Porter, American Hospital Association’s Regional Executive for Region 6 How to contact us: Sakakawea Medical Center 510 8th Ave NE Hazen, ND 58545 Phone: 701.748.2225 Fax: 701.748.5757 Visit www.aha.org for more information. -

Sleep-Related Movement Disorders and Disturbances of Motor Control

REVIEW CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) CURRENT OPINION Sleep-related movement disorders and disturbances of motor control Panagiotis Bargiotas and Claudio L. Bassetti Purpose of review Review of the literature pertaining to clinical presentation, classification, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of sleep-related movement disorders and disturbances of motor control. Recent findings Sleep-related movement disorders and disturbances of motor control are typically characterized by positive motor symptoms and are often associated with sleep disturbances and consequent daytime symptoms (e.g. fatigue, sleepiness). They often represent the first or main manifestation of underlying disorders of the central nervous system, which require specific work-up and treatment. Diverse and often combined cause factors have been identified. Although recent data provide some evidence regarding abnormal activation and/or disinhibition of motor circuits during sleep, for the majority of these disorders the pathogenetic mechanisms remain speculative. The differential diagnosis is sometimes difficult and misdiagnoses are not infrequent. The diagnosis is based on clinical and video-polysomnographic findings. Treatment of sleep- related motor disturbances with few exceptions (e.g. restless legs/limbs syndrome) are based mainly on anecdotal reports or small series. Summary More state-of-the-art studies on the cause, pathophysiology, and treatment of sleep-related -

Prevalence and Associated Factors of Nocturnal Eating Behavior And

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Prevalence and Associated Factors of Nocturnal Eating Behavior and Sleep-Related Eating Disorder-Like Behavior in Japanese Young Adults: Results of an Internet Survey Using Munich Parasomnia Screening Kentaro Matsui 1,2,3,4 , Yoko Komada 5 , Katsuji Nishimura 2, Kenichi Kuriyama 4 and Yuichi Inoue 1,6,* 1 Japan Somnology Center, Neuropsychiatric Research Institute, Tokyo 1510053, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Psychiatry, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo 1628666, Japan; [email protected] 3 Clinical Laboratory, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo 1878551, Japan 4 Department of Sleep-Wake Disorders, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo 1878551, Japan; [email protected] 5 Liberal Arts, Meiji Pharmaceutical University, Tokyo 2048588, Japan; [email protected] 6 Department of Somnology, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo 1608402, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-6300-5401 Received: 25 March 2020; Accepted: 21 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Nocturnal (night) eating syndrome and sleep-related eating disorder have common characteristics, but are considered to differ in their level of consciousness during eating behavior and recallability. To date, there have been no large population-based studies determining their similarities and differences. We conducted a cross-sectional web-based survey for Japanese young adults aged 19–25 years to identify factors associated with nocturnal eating behavior and sleep-related eating disorder-like behavior using Munich Parasomnia Screening and logistic regression. Of the 3347 participants, 160 (4.8%) reported experiencing nocturnal eating behavior and 73 (2.2%) reported experiencing sleep-related eating disorder-like behavior. -

Lipedema Intake Form

Lipedema Intake Form (Please complete in addition to a complete health history) Personal Information Name Do you sit for long periods at a work, home or DOB while driving? Yes No Have you been formally diagnosed with lipedema? If yes, please tell me more: Yes No Does someone else in your family have Lipedema? Do you experience stress? Yes No Yes No If yes, please tell me more: Have you been evaluated by an expert? Endocrinologist Yes No Does your stress result in any of these symptoms? Vascular Specialist Yes No (circle all that apply) Nutritionist Yes No muscle tension / anxiety / insomnia / irritability / other Physical Therapy for functional improvement - Is there a particular area of the body where you are (balance and movement) Yes No experiencing tension, stiffness, pain or other discomfort? Psychotherapist Yes No Yes No Other Yes No If yes, please tell me more: Tell me more: Are you experiencing discomfort in your body? Yes No What treatments have you tried in the past? How well did they work? If yes, please tell me more: Tell me more: Do you suffer from chronic pain? Yes No Are you currently under medical supervision for If yes, please tell me more: lipedema, lymphedema or any other condition? Yes No Do you have areas of swelling and/or inflammation? Yes No If yes, please tell me more: If yes, please tell me more: Do you exercise regularly? Yes No Have you had a recent injury or surgery? Yes No If yes, please tell me more: If yes, please tell me more: Do you perform any repetitive movement in your work or at home? Yes No Do you -

MR Imaging of the Lymphatic System in Patients with Lipedema and Lipo-Lymphedema

Microvascular Research 77 (2009) 335–339 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Microvascular Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ymvre Regular Article MR imaging of the lymphatic system in patients with lipedema and lipo-lymphedema Christian Lohrmann a,⁎, Etelka Foeldi b, Mathias Langer a a Department of Radiology, University Hospital of Freiburg, Hugstetter Strasse 55, D-79106, Freiburg i. Br., Germany b Foeldi Clinic for Lymphology, Hinterzarten, Röβlehofweg 2-6, D-79856, Hinterzarten, Germany article info abstract Article history: Objective: To assess for the first time the morphology of the lymphatic system in patients with lipedema and Received 30 October 2008 lipo-lymphedema of the lower extremities by MR lymphangiography. Revised 15 January 2009 Materials and methods: 26 lower extremities in 13 consecutive patients (5 lipedema, 8 lipo-lymphedema) Accepted 15 January 2009 were examined by MR lymphangiography. 18 mL of gadoteridol and 1 mL of mepivacainhydrochloride 1% Available online 27 January 2009 were subdivided into 10 portions and injected intracutaneously in the forefoot. MR imaging was performed with a 1.5-T system equipped with high-performance gradients. For MR lymphangiography, a 3D-spoiled Keywords: Lipedema gradient-echo sequence was used. For evaluation of the lymphedema a heavily T2-weighted 3D-TSE Lipo-lymphedema sequence was performed. MRI Results: In all 16 lower extremities (100%) with lipo-lymphedema, high signal intensity areas in the epifascial Lymphangiography region could be detected on the 3D-TSE sequence. In the 16 examined lower extremities with lipo- Microcirculation lymphedema, 8 lower legs and 3 upper legs demonstrated enlarged lymphatic vessels up to a diameter of 3 mm. -

Best Practice Guidelines

WUK BPG Best Practice Guidelines Te management of lipoedema 2017 Diagnosis and assessment Lipoedema management Life style support and self care Compression therapy Non-surgical and surgical interventions BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES: EXPERT WORKING GROUP: THE MANAGEMENT OF Tanya Coppel, Specialist Lymphoedema Physiotherapist, LIPOEDEMA Belfast Health & Social Care Trust, Belfast PUBLISHED BY: Julie Cunneen, Macmillan Clinical Lead for Wounds UK Lymphoedema Service/Nurse Consultant, Moseley Hall Hospital, Birmingham A division of Omniamed, 1.01 Cargo Works Sharie Fetzer, Chair, Lipoedema UK, London 1–2 Hatfields, London SE1 9PG, UK Tel: +44 (0)203735 8244 Kristiana Gordon, Consultant in Dermatology and Web: www.wounds-uk.com Lymphovascular Medicine, St George’s Hospital, London Denise Hardy, Lymphoedema/Lipoedema Nurse Consultant, Kendal Lymphology Centre, Kendal, Cumbria; Nurse Adviser, Lipoedema UK/ Lymphoedema Support Network (LSN), Cumbria; Co- Chair of the Expert Working Group © Wounds UK, March 2017 Tis document has been developed Kris Jones, Patient; Joint Managing Director & Nurse by Wounds UK and is supported byActiva Healthcare, BSN Consultant, LymphCare UK; Nurse Consultant, Medical, Haddenham Healthcare, Lipoedema UK Lipoedema UK, medi UK, Sigvaris and Talk Lipoedema. Angela McCarroll, Trustee, Talk Lipoedema; Patient, Northern Ireland Caitriona O’Neill, Lymphoedema Care Lead Nurse, Accelerate CIC, London Sara Smith, Senior Lecturer in Dietetics and Nutrition, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh Cheryl White, Lymphoedema Specialist